Proselytizing a New Way to Be Free: Elliott Landy’s Music Photography

The photographer reflects on making images of iconic figures, experiments with infrared color film, and how publishing images of a new generation of musicians was a way to ‘get people to come out of the old way of being’

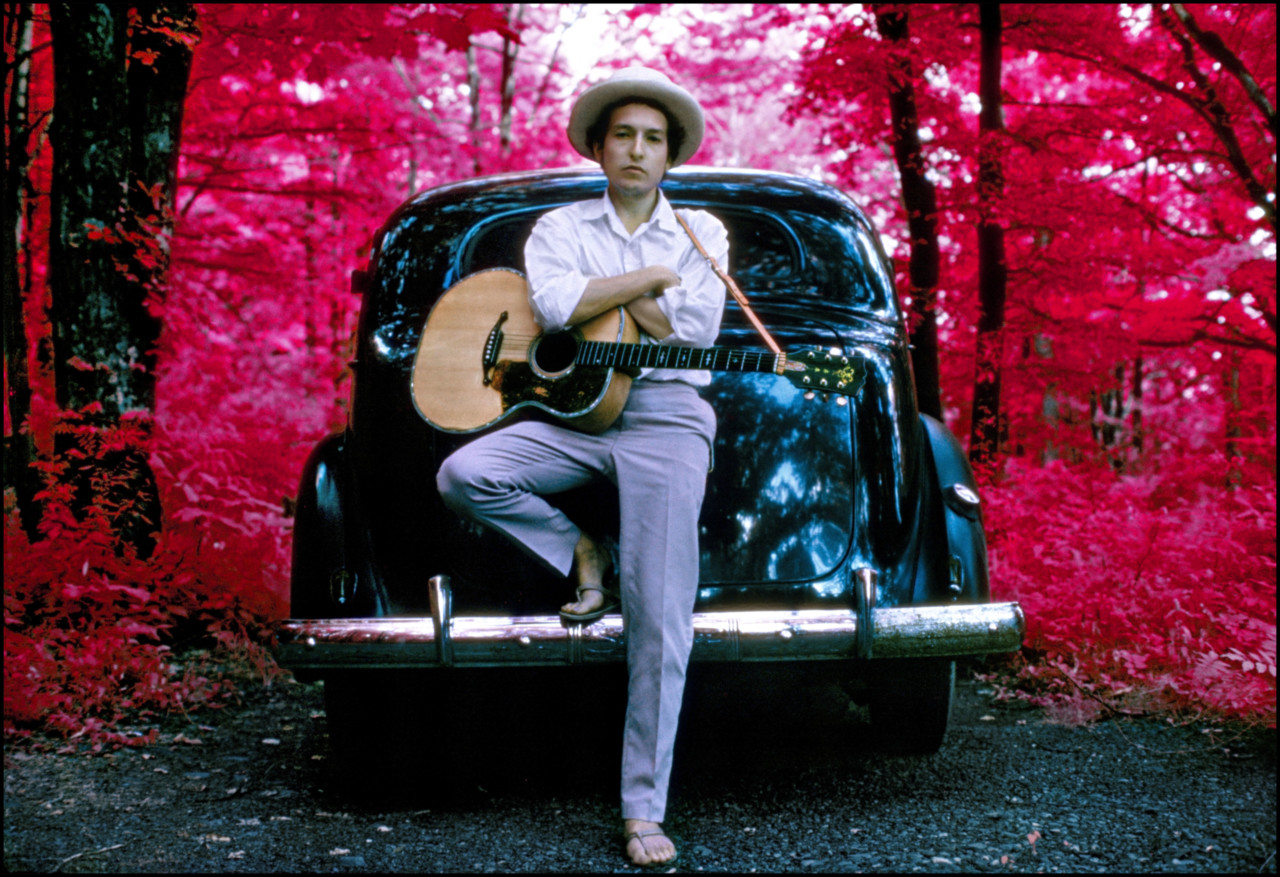

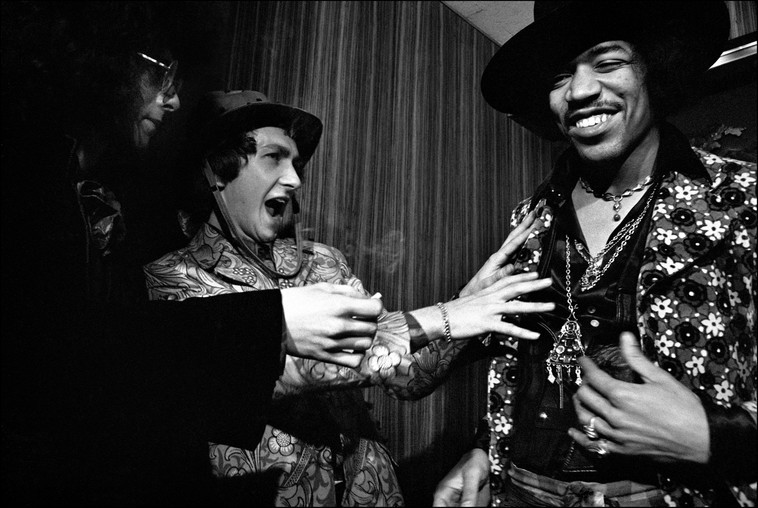

The above image by Landy is now available – for the first time ever – as a limited edition 8×10″ Magnum stamped print. You can see all images available in this new collection and learn more about the 8X10″ Magnum Editions prints here, on the Magnum Shop.

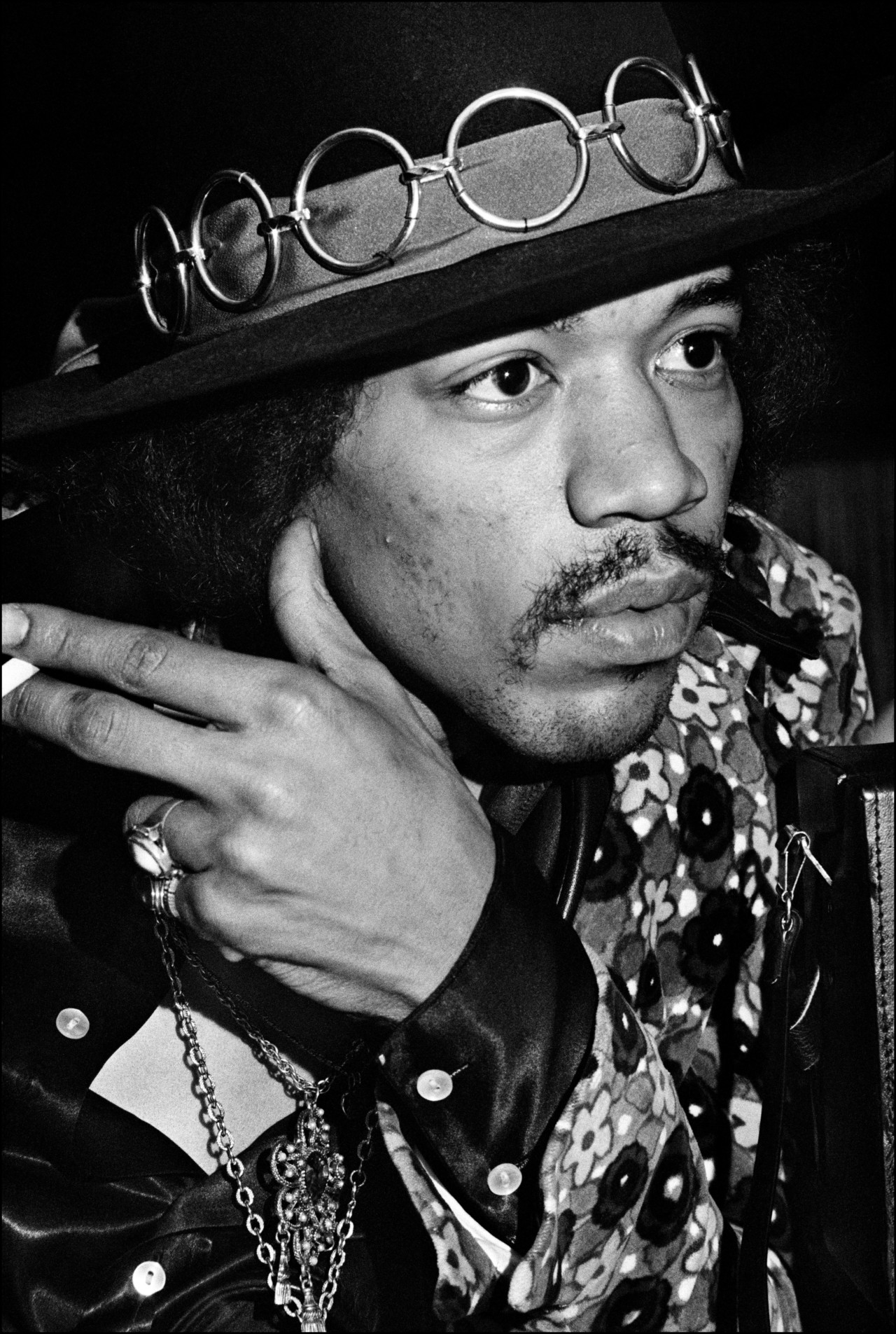

Elliott Landy, among the first music photographers whose work crossed into the art world, was one of the most prolific photographers of the 1960s’ music and youth scenes. Having started out documenting anti-Vietnam War protests, Landy photographed the seminal Woodstock ‘69 festival (he was an official photographer of it) which he described as ‘a moment of perfect human interaction.’ The photographer made some of the best-known images of musical icons like Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, and Janis Joplin amongst others – often employing radical approaches like the use of infrared film stock. Here Landy discusses photographing the famous, experimenting with technical innovations, and not seeing making images as ‘a job’.

Who was the first musician you photographed?

I think the first was Bob Dylan, at the Woody Guthrie memorial concert, where Dylan and The Band performed in 1968. I was thrown out of that concert by Albert Grossman, who was running it and was the manager of both Dylan and The Band. It’s a long funny story, and it’s in my book, Woodstock Vision, The Spirit of a Generation. It was the first time Dylan had performed for a year after he had a serious motorcycle accident—there were rumors that he had died or was permanently incapacitated.

Were you always very conscious of capturing the person behind their public persona as they truly are, their true character, not just the performer that the public knew them?

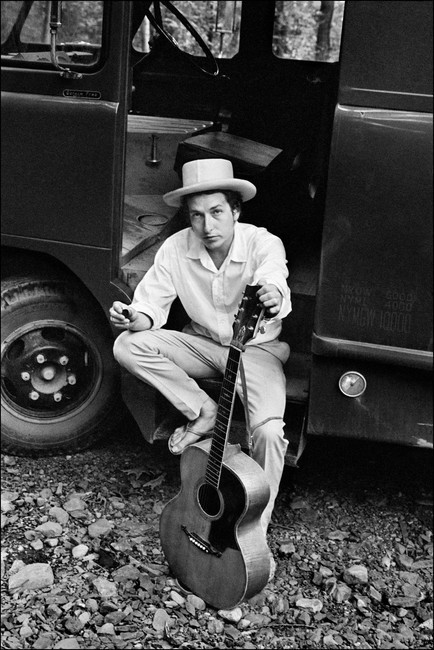

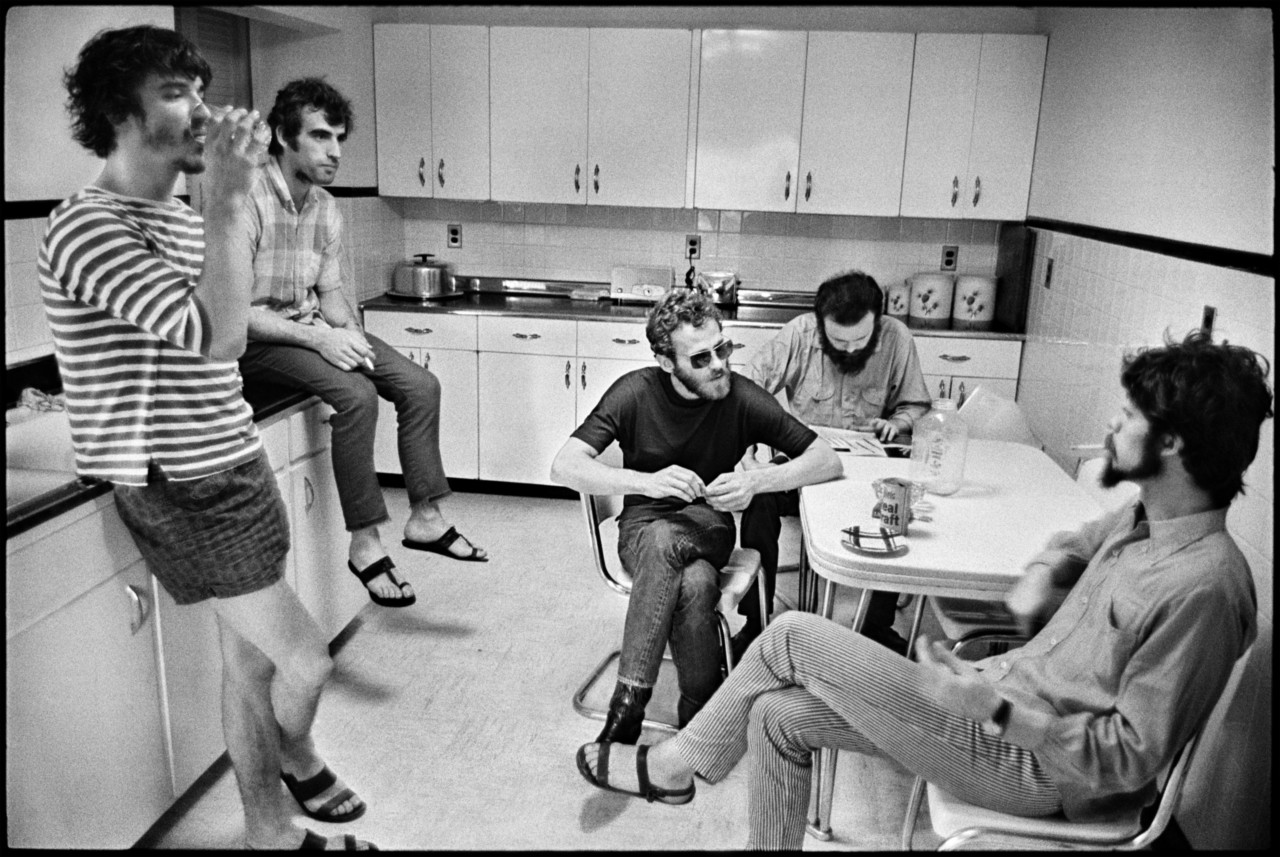

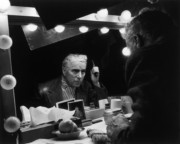

When I photograph someone, I am only concentrating on what they look like through the viewfinder and trying to catch that perfect moment when they look wonderful while part of a gorgeous composition. I am purely a part of a moving scenario with no other thought in my mind including who they are—their public persona—It is purely about me and them in the moment, moving around together to find the perfect image. Whatever way they look, wherever we happen to be, that’s it. Most of the time I just went along with what was. I say ‘most of the time’ because an exception is the photograph of The Band [used on the album] Music From Big Pink, which I had to stage to get a picture which they felt represented them.

"What I appreciated about [Dylan] was that he listened to me talk. Right? Here was this super smart, deep mind with so much to say, just listening..."

-

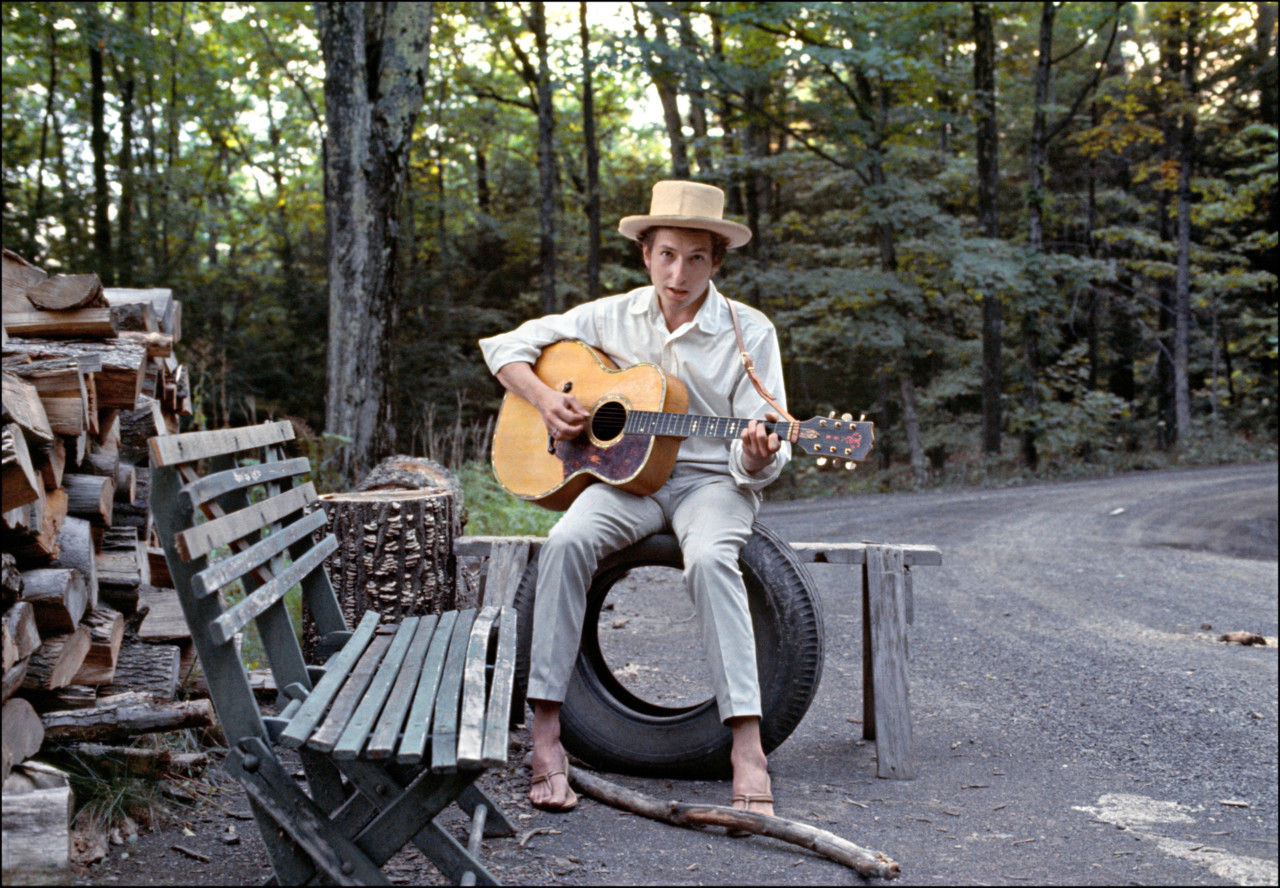

The first time I photographed Bob Dylan, he picked up his guitar and started to play and sing. I realized how special it was, “Here I am, ten feet away from this legendary great artist,” or something to that effect, who’s playing and singing just for me and what people would give to be in this position, in this situation. But to me, it feels normal. I just was aware that I was not at all shaken up by it or nervous about it. It just felt like any other time in my life. But I realized consciously that it wasn’t normal and was so special.

I wrote in my book, “Although he was comfortable with me, he was nervous in front of the camera and his uneasiness made it difficult for me. I was never the kind of photographer who talked people into feeling good. I let them be the way they were and photographed it. Usually it worked out.” I guess that’s because I flowed with whatever mood they were in without resistance, there was no tension and things usually lightened up. I was only interested in getting who they were and whatever mood they were in. I didn’t try to change their mood. Of course, if they looked ugly, I didn’t take a picture. I mean, my goal was to get a pretty picture always or a flattering picture because I don’t want to make anybody look bad.

"They felt comfortable with me because I didn't want anything other than a good picture of them. I was there to give them something..."

-

Do you think that’s what separated you from maybe other photographers who would just snap and not be as respectful? Because obviously your subjects seem to respect you a lot, as you respected them, and as you just said: you didn’t want to take a bad photo of them.

That’s interesting. I would say yes to that. I don’t compare myself to other photographers but I guess my innate respect for anybody, and desire to be nice to people, played a role in the way the pictures came out.

They felt comfortable with me because I didn’t want anything other than a good picture of them. I was there to give them something.

A picture for me was, and is, an expression of a beautiful moment in my life. Whoever I was photographing, Dylan, The Band or Janis Joplin, I had no ulterior motives. I was there only to capture and share something beautiful. It wasn’t a career move, I wasn’t taking the picture to make money or get famous. I think that got communicated to them and that’s why they felt comfortable with me and respected me. They sensed the purity of my motivation. It was for the Art and everything else was secondary.

Who did you especially enjoy photographing?

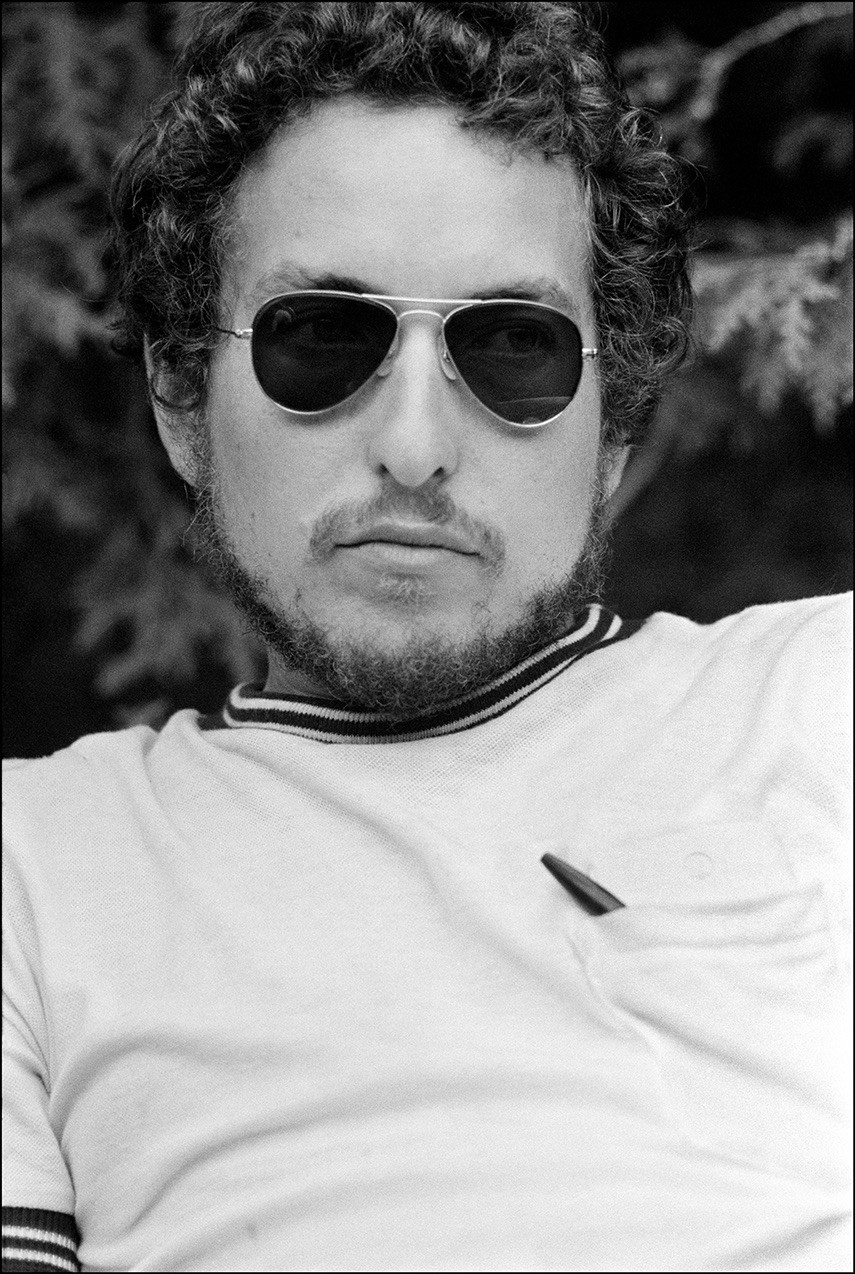

It was nice to be around Bob Dylan. In person, he’s as interesting as is his music. We had long conversations which were really nice—the longest I’ve had with any of the musicians I’ve photographed. We talked about a lot of stuff. What I appreciated about him was that he listened to me talk. Right? Here was this super smart, deep mind with so much to say, just listening. Of course, he did talk a lot during our conversations but I saw he was just as interested, or more so, in hearing what I had to say than talking about things with which he was already familiar.

He really wanted to know what he could learn from others. And I thought, “It’s really wise to be like that—to just listen.”

"I'm sorry I didn't photograph Jim Morrison more. I only did two concerts with him. But with some of the Jim Morrison photographs, I was moving with him. I was kind of dancing with the music"

-

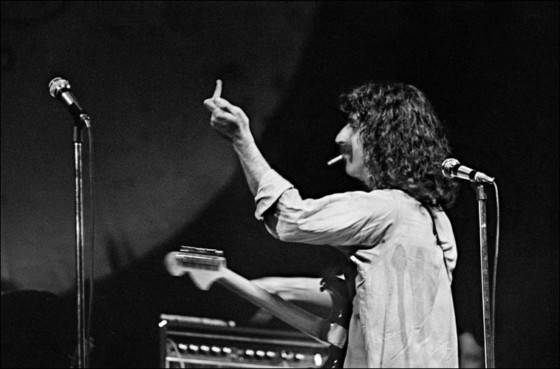

Speaking of that, how did you opt to capture performers such as Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison who always appeared to be in movement on stage, especially in your photographs?

Well, I’m sorry I didn’t photograph Jim Morrison more. I only did two concerts with him. But with some of the Jim Morrison photographs, I was moving with him. I was kind of dancing with the music. I set a slow shutter speed for those, and also for some of the Janis pictures. There are a few Janis ones that are quite nice which I haven’t shown yet, because they need to be digitally enhanced to bring out her face, which is in the middle of a blur of light. Sometimes I would try and play with that and sometimes I would just try and get a sharp, steady picture.

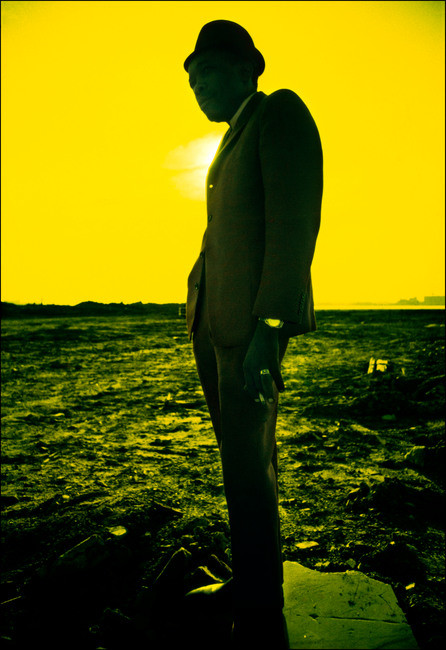

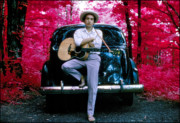

How did you come to use infrared film?

My first job was in Copenhagen in 1967, I lived there for about nine months. I met a guy, he was German and he showed me his pictures taken with infrared colour film. He showed me a sheet of slides, and said, ‘Look, you use this film and you get all these crazy colours.’ I thought that was interesting and tried it out when I got back to the States and I really loved it.

It was very hard to use because, number one, you had to focus on a different point than when you focus visually using normal film. So you have to constantly look down at the lens to adjust it to the infrared focus point. And that was very difficult because for me, the photographic process is a fluid one. I’m taking pictures and I don’t ask people to do anything. I move, they move. I don’t say ‘move over here, move over there.’ So it breaks the flow.

And then also you need color filters because if you don’t use a color filter, it comes out very purple. So Kodak recommended a yellow filter to make it look a little more normal. In those years, I didn’t have a screw in filter so I had to use thin plastic gelatin filters which I had to hold in front of the lens while taking the picture, holding the camera and so on. And then I would experiment with other color filters. I used, green, yellow, blue and orange filters just to see what would happen.

Also, you couldn’t take an accurate light meter reading because infrared light wasn’t measured by a regular light meter. They did have scientific type infrared light meters but they were very complex and certainly more expensive than I could afford at the time. So you weren’t sure what you were going to get when you took the picture and I had no idea what the color was going to be like either, which I like. I don’t mind. I like to be surprised because that shows me something I don’t know yet. So I just did it whenever I could physically.

Always when you’re photographing, you kind of have a job. When I was photographing The Band, for example, my job was to get good pictures of them. So if I’m using a camera with infrared film and don’t know what it’s going to look like, then I’m giving up a chance to get what I’m supposed to be doing, and want to be doing there. But luckily I had enough time with The Band, so that after I got the normal photos which were required, I could take the time and switch over to infrared. But with Dylan, I only took two photographs in infrared. I can’t believe I took so few, but that’s all I have and one of them is my most popular picture. Life magazine published the other one once. It’s not as good a photograph but I’ll probably put out a limited edition of it at some point because people are interested in outtakes.

"Do I have one favourite? No. Do I have a lot of favourites? Yes! I think the thing is I still like them. I like them all..."

-

Of your photographs, do you have a favourite?

I love the infrareds—there’s a whole series and some of them are, really ‘wow’! Do I have one favourite? No. Do I have a lot of favourites? Yes! I think the thing is I still like them. I like them all—the black and whites and normal color and concert color, etc. That’s why I keep working with them. I never fail to admire a print I make of them.

Did you have a favourite camera to use?

Well my favorite one was the one I needed to get the shot I wanted to get. So it kept changing. But I did have special equipment. I worked with two Leica’s and two Nikons and a Widelux panoramic camera which, except for Woodstock, I never used successfully.

In those days you couldn’t make quality black and white reproductions from color film for newspapers and magazines so you had to shoot both types of film which meant having two sets of cameras. You shot one and then the other. Today you can easily reproduce color film as black and white in publications and online.

To photograph something I needed a range of lenses—wide angle (28mm), normal (50mm) and telephoto (105, 180 and 300 mm.) I used Leicas for wide angle and normal photos and Nikons for normal and telephoto shots. The Nikon 105mm F 2.5 was my all time favorite portrait lens. It was just great because it focused very close. I even purchased an old one just now so I can adapt it to my current camera and see if it still gives me the old magic look.

For telephoto shots, I had 180mm F2.8 and 300 mm F 4 Zeiss lenses. In those years pro photographers used Nikon cameras because it was the best single lens reflex at that time. It had a bright viewfinder so you could see the picture you were taking and it had a built in exposure meter, which I never used but was the beginning of how photos are taken automatically today. The fastest medium telephoto lens they had was a 200 mm F4, which was not really fast enough to do what I needed. However Zeiss, in East Germany, made a 180mm F2.8 lens which gave me one more (crucial) F stop of light. I had it adapted to work on my Nikons by Marty Forscher. The extra F stop really enabled me to do my concert stuff because the stage lighting was relatively dim compared to today, and film was very slow compared to digital media today. Today with hi-tech lighting and super sensitive digital cameras, it’s like having super fast film which did not exist in those years. My color photos were shot with High Speed Ektachrome type B film, ASA 125. It was balanced for tungsten light. I push processed it two stops to 500 ASA and even with that and my 2.8 lens, my color exposures were down to a 1/15th or 1/8th of a second, rarely a 30th and with everybody dancing around you, it was quite a feat to hold the camera still. But the lens was cast iron so its inertia helped me keep it steady, unlike today where everything is so light that it moves very easily. I also used a Leitz table top tripod and ball camera head. I attached it to the lens and pressed two of its legs tightly against my chest, with the eyepiece of the camera pressed tightly to my eye, making a three point stable support, and held my breath when pressing the shutter, to keep that camera steady.

"I felt that when I was photographing these concerts and photographing the musicians on stage dressed the way they were and publishing them In newspapers, it was, for me, proselytizing, trying to get people to come out of the old way of being and be part of this new culture"

-

Was there anyone you would have liked to photograph and didn’t?

Well, you know, I guess photographing Pink Floyd would have been nice. The first psychedelic concert I ever went to was in Copenhagen and it might have been Pink Floyd. My girlfriend took me to a concert. I had never seen a light show before. It was my first experience. I wasn’t a fan of their music in the ’60s, but I am now, so that would have been nice. But as far as missing photographing them, I don’t know how worried I am – I managed to get some pretty colourful people in my pictures already!

Now, looking back, you see, I was very casual. When I did this stuff, I wasn’t on a career thing. I wasn’t doing it to create a library. I needed to make money from my work and sold a few here and there, but I didn’t take the photos to make money. I was giving my pictures away to underground newspapers like The Rat and The New York Free Press, which were against the war. I was photographing peace demonstrations to show how many people were against the war and to try and stop it. In those days, major media gave very little photographic coverage to these events. I began photographing these concerts by chance.

I felt that when I was photographing these concerts and photographing the musicians on stage dressed the way they were and publishing them in newspapers, it was, for me, proselytizing, trying to get people to come out of the old way of being and be part of this new culture, a new way of thinking, a new way of being free. You can dance any way you want, you can be free, you can express yourself freely. That’s the whole point of life, I guess. to learn to express yourself freely while being considerate of other people. So that’s what I was really doing there, saying “Come be part of this, smoke a joint, be against the war.” For me, that’s what the music photography was about. And as I write in my book, “I was never a fan.” I wasn’t there because I was a fan of the music. I was there because the music was fantastic. None of the iconic stars had become famous yet. Even when I went to see Bob Dylan at the Woody Guthrie Memorial concert, it was more because he was part of the social movement. But a year later, when I asked him about that, he said he didn’t mean to be a part of a social movement. He just wrote what came into his head. He said something like, ‘I’m good with words, I know how to use words and how to shape words and that’s what I do. I pick up what’s in the air and put it into words.”