René Burri’s Brasilia

To mark the anniversary of the city's inauguration, we reflect on Burri's study of its construction

Brasilia, capital of Brazil, was inaugurated on April 21, 1960. The city was planned and built during 1956–1960, drawing upon the greatest minds the nation had to offer in terms of architecture, planning, landscaping, and construction: names like Oscar Niemeyer, Lúcio Costa, and Roberto Burle Marx.

Swiss photographer René Burri had been capturing subjects as diverse as Le Corbusier’s work, Picasso in his home, and Argentine gauchos when he found himself flying to Brazil to document the city as it rose from the ground with astonishing pace. He photographed the area from its earliest days as a near-untouched wilderness, through months of gargantuan construction, and documented its completion and revelation as a treasure of modernist architecture and a focal point for Brazilian optimism. As Arthur Ruegg, professor in architecture and construction, wrote in his essay ‘Rene Burri’s Journeys to Brasilia’, “Scarcely any other twentieth-century monument is more spectacular and more photogenic.”

Here, to mark the anniversary of the city’s inauguration, we republish Ruegg’s extensive essay in full, taken from the book Brasilia, published in 2011 by Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess.

René Burri’s Journeys to Brasilia

Rene Burri first flew to South America in 1958. Instead of the planned three weeks, he stayed for six months, fired by an almost superhuman zest for action. The photographer’s cooperative Magnum had just turned down his application for full membership — a bitter blow for such an ambitious photographer. Henri Cartier-Bresson had told him “Tu as bien travaille, mais tu es trop jeune.” Born in Zurich in 1933, Burri had entered the world of photojournalism three years earlier with an illustrated report on Mimi Scheiblauer, a Zurich-based music pedagogue who worked mainly with deaf and speech-impaired children. His six-page report published in the French magazine Science et Vie had won him temporary accreditation with Magnum.

Burri had learned how to capture aesthetically pure, artfully composed and illuminated objects – Swiss object photography in other words – at the Zurich School of Art and Design, where his teacher was Hans Fisler (1891-1972), the supreme master of subtle gray tones. The climate of the early fifties was remarkably conducive to this austere, rigorously objective style, and Burri fell under the same spell, inspired not least by Alfred Willimann, whom Finsler had recruited to teach typography and graphic design. At the same time, Burri was in revolt against the homogeneity of the Finsler school. He was fascinated by chaos, interested in people, and wanted to be out “on the streets.” A School of Art and Design film stipend awarded to him in 1953 gave him an opportunity to assist the director Ernst A.Heiniger on one of the first cinemascope films ever shot in Switzerland. For Burri it marked the turning point, after which he allied himself with the other main current in Swiss photography. This was the style which without disregarding aesthetic principles subscribed to the humanistic tradition of photojournalism as practiced by the Zürcher Illustrierte of the nineteen-thirties and the arts and culture monthly Du of the nineteen-forties. Finsler’s first top student had pulled off just such a volte-face some years before Burri – and in exemplary fashion, too: When Werner Bischof (1918-1954) published a representative selection of twenty-four photographs in 1946, he was effectively drawing a line under all the highly subtle experiments with light that had gone before. Only after emancipating himself from the obsessive pursuit of “beautiful images” could he capture the horrorscapes of postwar Europe on film. Like Burri after him, he became a “committed” photographer and the first Swiss member of the new photographers’ cooperative Magnum in Paris.

Mid-fifties Magnum proved an ideal nurturing ground for Burri and before long he was chasing after the story to end all stories. From now on, he was constantly “en avion,” as Cartier-Bresson was wont to say, and his radius of action grew by the year. Soon he was in Germany, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Egypt, Spain, Greece, and Turkey – wherever there were “shifts in the political, social, and historical fault-lines that could be recorded in distinctive visual metaphors.”

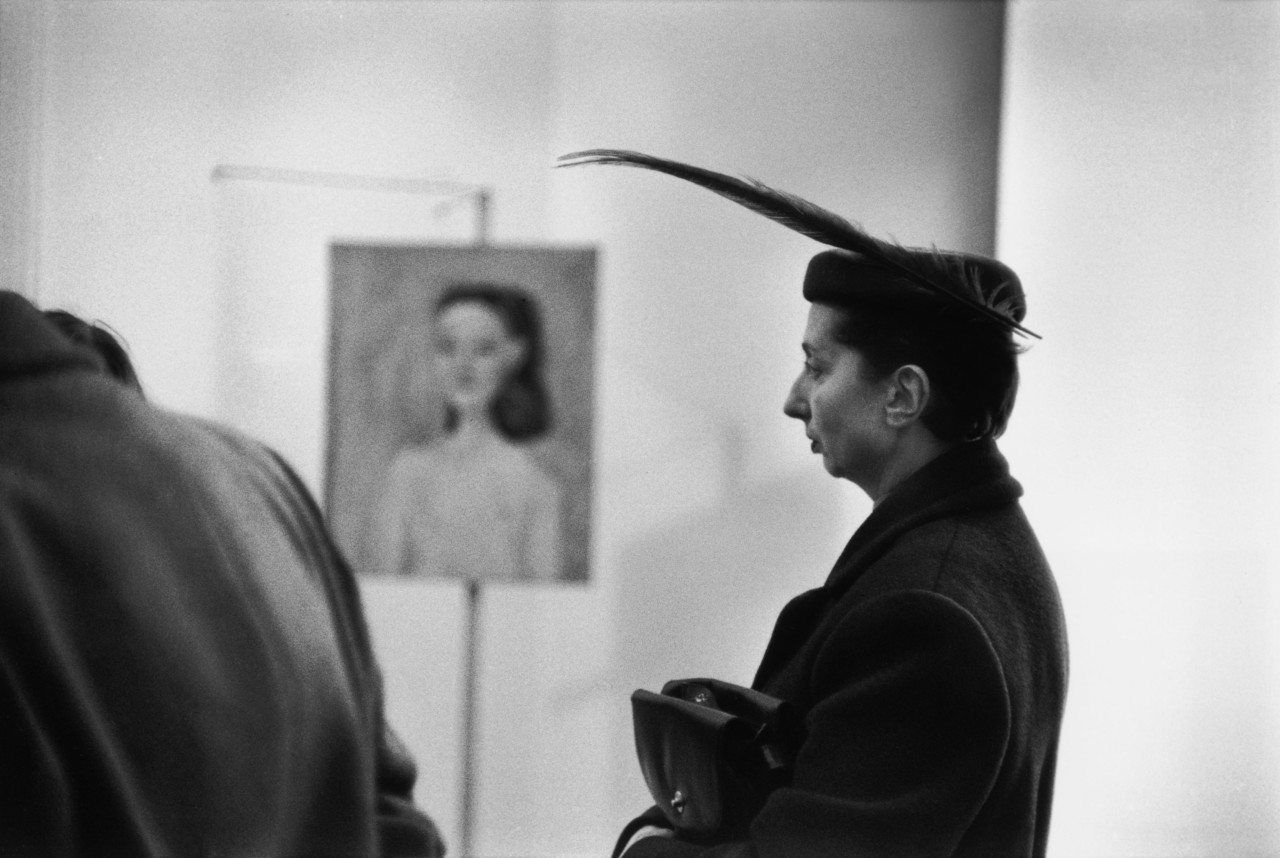

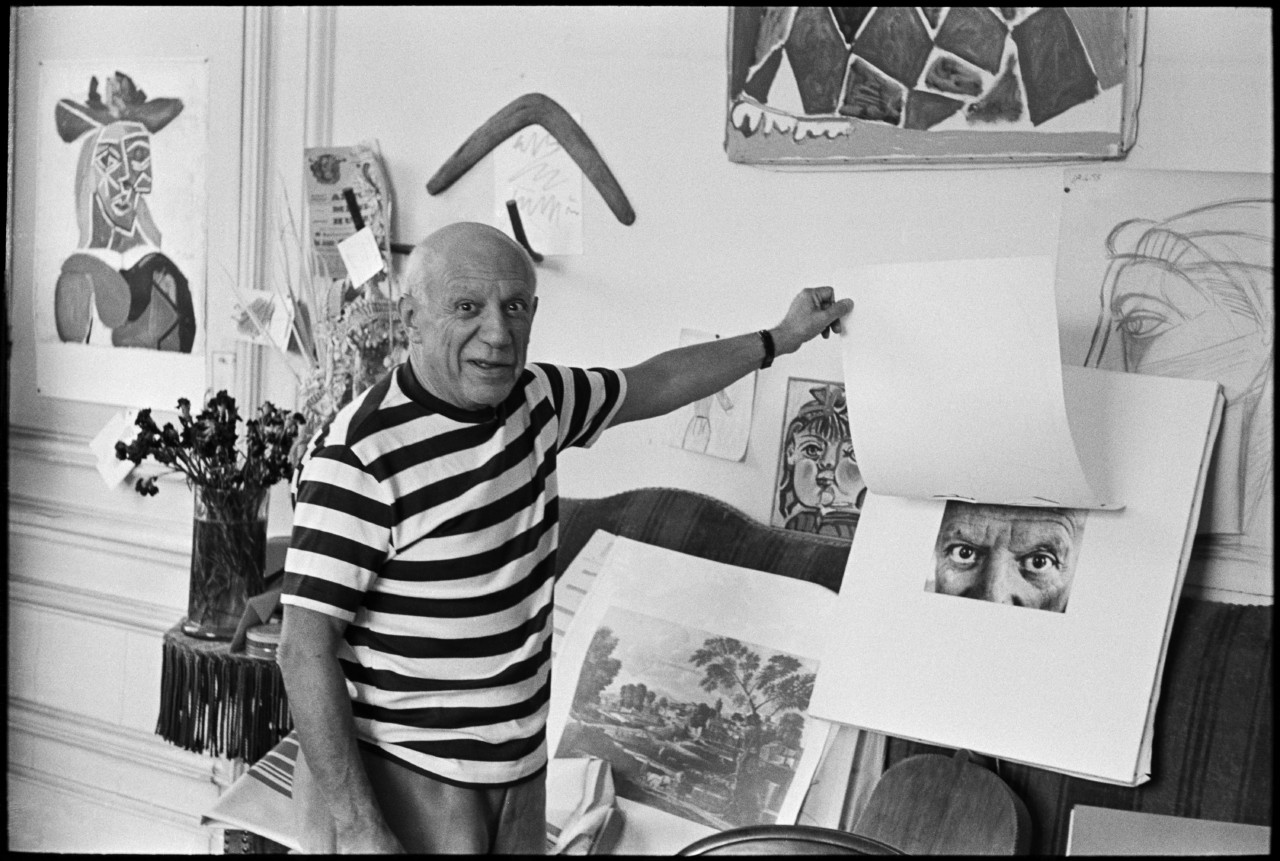

Burri eschewed both the merely anecdotal as well as obscene depictions of barbarity. With remarkable speed and self-assurance, he found his own style in formally harmonious compositions out of which, using a minimum of means from a wide range of sources, he was able to distill stories of parable-like reach and validity – not least from the world of art and architecture. One wonderful sketch of 1951 shows visitors to the partially destroyed Palazzo Reale in Milan interacting with the Picassos exhibited there. Then, in 1955, he photographed the consecration of Le Corbusier’s chapel in Ronchamp – the first of his works to make a mark on Paris Match. The photographs of his first encounter with Picasso himself in Arles in 1957 likewise acquired iconic status and were included in a special edition of Du devoted exclusively to Picasso.

"In 1955, he photographed the consecration of Le Corbusier's chapel in Ronchamp - the first of his works to make a mark on Paris Match. The photographs of his first encounter with Picasso himself in Arles in 1957 likewise acquired iconic status..."

-

From Argentina via Peru to Brazil

It was Du editor-in-chief Manuel Gasser who in the critical year 1958 enabled Burri to strike out on his own toward new horizons. Burri had told him about Don Segundo Sombra, Ricardo Güiraldes’s now legendary tale of Argentinian gauchos, the German translation of which had just recently been published. Gasser was so excited by the idea of a photo project on the subject that Burri set off for Buenos Aires in search of the famous South American cowboys just a few weeks later. Unable to locate either the author of the novel– who had died in 1927 – or even a single gaucho, however, he busied himself with other projects instead, including shooting the inauguration of Argentina’s new liberal President Arturo Frondizi in a ceremony attended by US Vice President Richard Nixon for the New York Times. It was at this juncture that Burri ran into the Englishman Brian S. Kingston at a party. Kingston had gone to Argentina for Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, but was now living the life of an adventurer. The young Swiss thus had no difficulty winning him over to the idea of writing about the gauchos. Chance was on their side, moreover, as their host that evening was one Manuel Ordonez, a great admirer of Magnum photographer Robert Capa. Ordonez decided to help Burri on his way by placing a brand new blue station wagon at his disposal the very next morning. Burri and Kingston then spent two months in the pampas, where Burri at last succeeded not only in discovering Güiraldes’s legendary world of the gaucho, but also in capturing this “twentieth-century Don Quixote” on film. It was a world “whose center is its inner self but whose borders are infinite,” as the photographer himself wrote, doubtless aware that he was at the same time describing himself. In 1959, “El gaucho” became the first of several specials that Burri (with texts by Kingston) produced for Du. Nearly a decade later, he revisited the subject in Gauchos, his second major photo book of 1968 with a foreword by Jorge Luis Borges and texts by José Luis Lanuza.

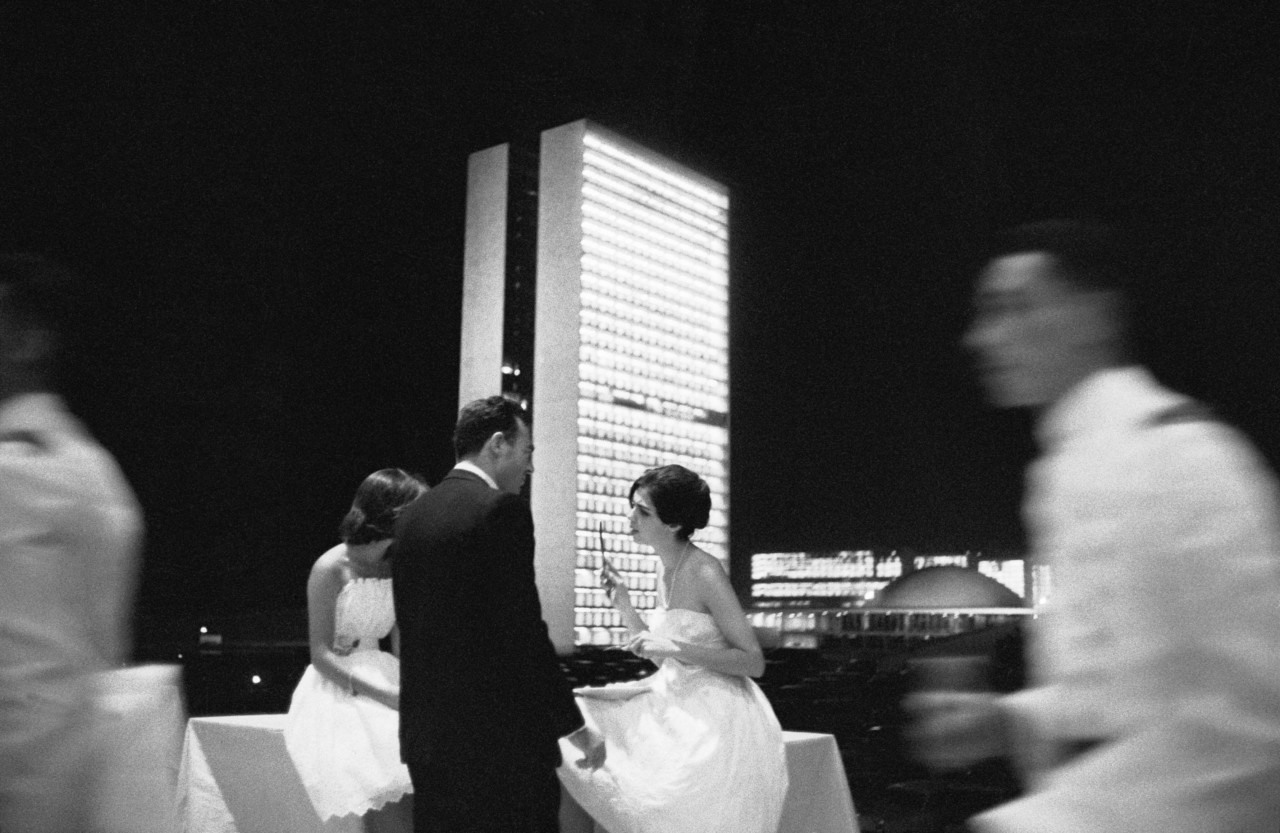

After several weeks spent working on various estancias in the province of Buenos Aires, Burri had become so acclimatized to South America that he and Kingston decided to drive their jeep all the way from Buenos Aires to Lima and back again – a journey of 14,000 km over some very rough terrain. He then moved on to Rio de Janeiro with the intention of producing a portrait of the city and making it his new base-camp. When it was announced that US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles was to visit President Juscelino Kubitschek, Burri was tasked with recording the event on celluloid. The politician’s large press retinue thus included a young Swiss photographer who was only too glad of the opportunity to venture deep into the interior all the way to Brasilia. In those days, of course, the new capital was no more than a giant building site, and what Burri glimpsed from the plane as they came into land looked more like a gargantuan Land Art project or one of the ancient city-states of Central America than a modern capital. His photographs show a highland plateau still dotted with scrub but at the same time engraved with lines and furrowed with long rows of earthworks; and then, near a wildly meandering river, a finely proportioned, snow-white complex so dwarfed by its surroundings that it looked more like an architectural model. This was the Palácio da Alvorada, the new presidential palace and the first government building to be completed at the end of June 1958. Burri captured the arrival of the two statesmen and their exchange of greetings on the tarmac; he also shot the crowds of jubilant schoolchildren from Brasilia’s first ginásio and the state banquet that followed at the Brasilia Palace Hotel. But apart from the odd glimpse or two of the Alvorada, he had no time for the as yet nascent city. This was soon to change, however, for Brasilia was to become one of the great projects of Burri’s career – one which he would work on for many years to come, and which [his] book presents in its entirety for the very first time.

Brasilia

Scarcely any other twentieth-century monument is more spectacular and more photogenic than Brasilia. It is certainly not the only modern city to have been built from scratch, but with the exception of Chandigarh, the capital of the Indian state of Punjab that Le Corbusier had designed just a few years earlier, not one of these other new cities fired the imagination as did Brasilia. The epic scale of it, the architectural ambition, and the breakneck speed at which Brazil’s policymakers wanted it built gave it all the hallmarks of a fantastical, reality-bending story such as the world had never seen before.

Brasilia embodies all the allures of modern architecture as well as Kubitschek’s promise of accomplishing “fifty years of progress in five.” Yet the idea of moving Brazil’s capital away from the coast and into the heartland of this immense country – with a land mass of 8.5 million square kilometers, Brazil is not much smaller than the United States – in fact dates back to the nineteenth century. The colonial power Portugal had chosen Rio de Janeiro as its seat of government in 1763, so when Brazil gained independence in 1822, there was talk of building a new capital to be called Petrópole or Brasilia in what is now the “Triângulo Mineiro” in the state of Minas Gerais.” The dream was never actually buried, but nor did it feature on the agenda of those in power. This did not change until the mid-twentieth century when Juscelino Kubitschek (1902-1976), the charismatic governor of Minas Gerais and the presidential candidate of a center-left coalition, was elected president in October 1955 and sworn in at the end of January 1956. As mayor of Belo Horizonte and later as governor, Kubitschek had been making a name for himself as a patron of modern architecture ever since 1940, and had found in Oscar Niemeyer (born 1907) an ideal partner. Niemeyer, one of Brazil’s leading pioneers of modern architecture, became the author of the exemplary architectural set built on the artificial lagoon at Pampulha in Belo Horizonte. As president, Kubitschek could easily have pleaded the excuse of being too busy running the country to build a new capital. Instead, he used his very first “message” to the Brazilian Congress on March 15th, 1956 to declare himself in favor of a new capital. His draft bill came into law on September 19th and the competition for the “pilot plan” opened that same day. The Congresso Nacional agreed a completion date for the new capital of April 21st, 1960, the day when Brazil’s national hero Tiradentes – an anti-Portuguese conspirator – was executed in 1726. Little wonder, therefore, that we find Niemeyer already hard at work on the project in September 1956. Not only was he to be one of the jurors of the competition, but that same month he was appointed chief architect of the state-financed Companhia Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil (NOVACAP). In October, moreover, it took him just ten days to erect the two-story wooden “palace” that was to be the first of the president’s residences on the site of the future capital, which in those days could be reached only by air. The “Cidade Livre,” a temporary township erected to house the workers was built just a short time later.

"Scarcely any other twentieth-century monument is more spectacular and more photogenic than Brasilia. It is certainly not the only modern city to have been built from scratch, but with the exception of Chandigarh, the capital of the Indian state of Punjab that Le Corbusier had designed just a few years earlier, not one of these other new cities fired the imagination as did Brasilia"

-

On March 16th, 1957, the prize for the best pilot plan went to Niemeyer’s erstwhile teacher Lúcio Costa. What had impressed the jury was not just the quasi-pharaonic stature of Costa’s vision (“Pharao Juscelino” was one of Kubitschek’s many nicknames), but also the rationality and hence practicability of a layout based on strictly functional criteria. A single monumental axis, the Eixo Monumental, was to link the site for small local industries in the hinterland with the main centers of culture, the government buildings, and the Three Powers Plaza built on a tongue of land projecting out into Paranoá Lake, the artificial lake created by damming the River Paranoá. The residential districts were to be built perpendicular to the Eixo Monumental along a bow-shaped strip following the curve of the lakeshore. The platform for the city’s transportation systems that Costa situated at the intersection of these two axes was to house a shopping mall and leisure center at the top and the central bus station at the bottom. Costa’s signature “P.P.B.” (Plano Pilôto de Brasilia) combines the intersecting streets and avenues of the grid layout so beloved of the Romans with Le Corbusier’s vision of a Ville radieuse. Remarkably true to Le Corbusier’s postulates are the apartment blocks erected on the 300 x 300-meter superquadras, which to this day allow the landscaped parkland on which they are built to flow through them unhindered. Yet the idea of subdividing the city into distinct neighborhoods each with its own green belt can be traced back to an Anglo-American tradition, specifically to Clarence Perry’s concept of the Neighborhood Unit (1929). The rules of the Plano Pilôto allowed some latitude with regard to the residential units to be built for the 3,000 inhabitants of each superquadra, and the numerous architects entrusted with designing them made liberal use of this.

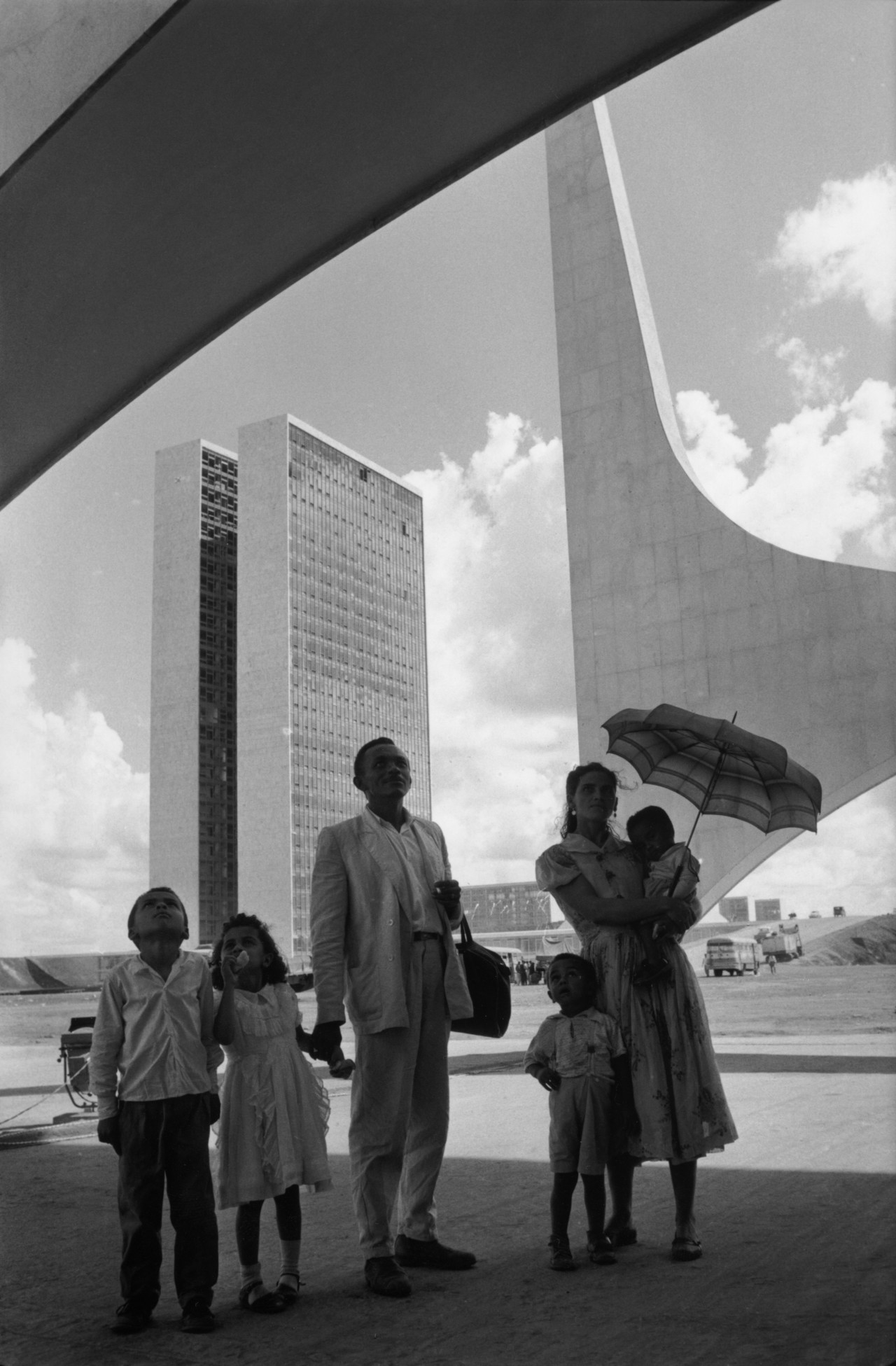

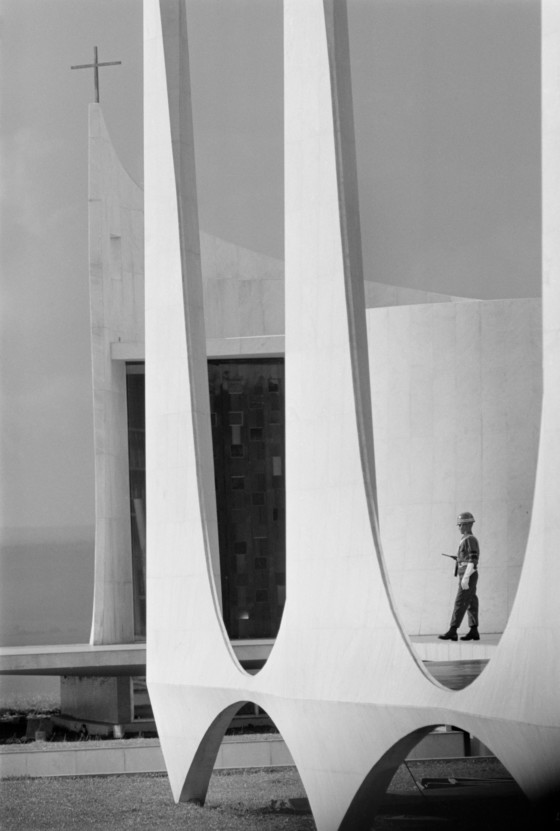

Unlike the apartment blocks, almost all the government buildings were the work of Oscar Niemeyer. The Palácio da Alvorada situated on the lakeshore beyond the Eixo Monumental and the Brasilia Palace Hotel was completed as early as mid-1958 and was followed in quick succession by the Supremo Tribunal Federal (the Supreme Court), the Palácio do Planalto (the seat of government), the Congresso Nacional (the famous Assembly building with the twin towers of the Secretariat), and the eleven ministries, as well as the Museu de Brasilia, all of which were inaugurated as planned on April 21st, 1960; the Palácio Itamaraty (housing the Foreign Ministry) and Catedral Metropolitana de Nossa Senhora Aparecida (the Roman Catholic cathedral) followed in 1970. This Herculean feat was possible only because planning in Brasilia was just one step away from realization, because there was an experienced team of urban planners, artists, and architects on hand ready to start work right away, and because the planners had Niemeyer’s crystal-clear design sketches to work from. The god that Niemeyer invoked was always Le Corbusier, the great inspiration behind modern Brazilian architecture, even if the point of invoking him was frequently to negate the classical modernist model he espoused. In one of his many ideogrammatic comparisons, Niemeyer pitted Le Corbusier’s slim, “crossed-out” pilotis against the skeletal façade supports that he himself favored. What he wanted was to “find forms which, though they may run counter to certain functional requirements, characterize the new buildings by lending them greater lightness so that they seem to be floating or resting only very lightly on the ground. This is the justification for the forms applied and the pointed ends. These forms afford the visitor new and unexpected views. Before long he sees them as a series of harmonious curves. Before long, standing in the middle of the Three Powers Plaza, he feels as if enveloped in a fan and in its play of plasticity, constantly changing, constantly taking on different guises, as if it were not at all an inert and immovable thing.” Concentration on just a few, visually effective designs often went hand in hand with the use of purely geometrical forms. One especially impressive example of this is the iconic Assembly building with its two hemispheres and tall and slim twin towers. Convinced that “architecture is not simply a matter of engineering, but an expression of the spirit, the imagination, and poetry,” Niemeyer set out to lend Brasilia what he himself called a “character of great monumentality.”

"The god that Niemeyer invoked was always Le Corbusier, the great inspiration behind modern Brazilian architecture, even if the point of invoking him was frequently to negate the classical modernist model he espoused"

-

The new palaces supplied the perfect backdrop for that lamentably short period of upbeat nationalism during which Brazil, under the leadership of the idolized President Kubitschek, appeared to be overcoming its backwardness and relative unimportance once and for all. Yet even a brief visit to Brasilia is enough to expose certain weaknesses in the city built from scratch. Writing just recently, Harper’s Magazine columnist Benjamin Moser was damning in his verdict on Niemeyer’s monumental buildings: “Except for the elegant Foreign Ministry, none offers anything beyond a startled first impression. There is nothing to see, no reason to linger. Once you have seen the postcard, you have seen the building.” The schematic row of uninspired hotels lining the Eixo Monumental in his eyes is no more capable of acquiring a distinctive identity than it is of arousing interest. The strict separation of functions envisaged in the Plano Pilôto has prevented the emergence of mixed-use urban spaces and given rise to traffic problems of gigantic proportions – especially since almost all of those who flocked to the rapidly growing capital had to settle in far-away satellite towns. “Brasilia’s difficulty lies in its self-imposed fetters,” complained Sigfried Giedion as early as 1960. One such “fetter” was the target population of half a million inhabitants underlying the plans: “The factor of the unforeseen cannot be disregarded,” he cautioned, “especially not in urban planning.” Brasilia today together with its many satellite towns already has a population of 2.5 million. Yet most candangos – as the people of Brasilia are known – seem perfectly adapted to their test-tube city. If the famous Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector is to be believed, the new capital has even spawned a new species of human: “Brasilia is artificial. As artificial as the world must have been when it was created. When the world was created, it was necessary to create a human being especially for that world”.

Burri’s View of Brasilia

Unlike now, when the verdicts range from the intrigued to the dismissive, the media of the day hailed Brasilia as a triumph and there can be no doubt that it was above all the photographers who turned the brand-new city into a worldwide media event. Photo-journalism in high-circulation magazines became far more than a mere service; on the contrary, it was “the undisputed ruler in the realm of photography,” as Gasser put it in Burri’s “El gaucho” edition of Du: “All the great photographers of the younger generation are at the same time reporters and see photojournalism in grand style as their ultimate calling, the true purpose of their work.” Little wonder, therefore, that NOVACAP in January 1957 launched its own lavishly illustrated magazine Brasilia in order to market the development of the construction site littered with state-of-the-art machinery for as long as possible.” NOVACAP even engaged its own photographer, the aircraft engineer Mário Fontanelle (1919-1986), whom President Kubitschek had taken a particular shine to. Fontanelle was the author of the magical aerial shots of the Plano Pilôto’s main intersection scored by bulldozers into the highland plateau. While Niemeyer engaged a personal friend of his, the French photographer Marcel Gautherot (1910-1996), numerous magazines and agencies dispatched photographers of their own to capture the genesis of Brasilia on film, among them Alberto Ferreira, Thomaz Farkas, Jean Mazon, Peter Scheier, and of course René Burri for Magnum – each of whom naturally had his own angle on the city.”

"Symbolism was part of Brasilia's history right from the start, but symbolism alone was nothing without monumentality, sentimentality, and kitsch. Burri was not afraid of turning the spotlight on this explosive combination"

-

While Burri, who was a generation younger than Gautherot, represented what Gasser called “photojournalism in grand style,” the Frenchman who had been working in Brazil since 1939 delivered sharply drawn, perfectly composed architectural photographs, in which people often look like hired extras. Thus his work is very much in the spirit of his contemporaries Julius Shulman and Ezra Stoller, the two great chroniclers of North American architecture. Possibly the most exciting of his iconic photos, however, show the steel skeletons of the unfinished ministries and the Secretariat as little more than a blurred backdrop rising up out of the dust like a shimmering Fata Morgana, while the brightly lit lunarscapes in the foreground with their mounds of sand crawling with workers are sharply in focus. The pathos of these images reminds Kenneth Frampton of the films of Socialist Realism. And Gautherot used a variety of techniques to make them more expressive still, among them fragmentation and concentration on material textures or on the contrast between areas of light and shade. Yet he never strayed as far from documentary photography as did Lucien Hervé, who in those same years was translating Le Corbusier’s government buildings in Chandigarh into black-and-white compositions so abstract as to be scarcely localizable at all.

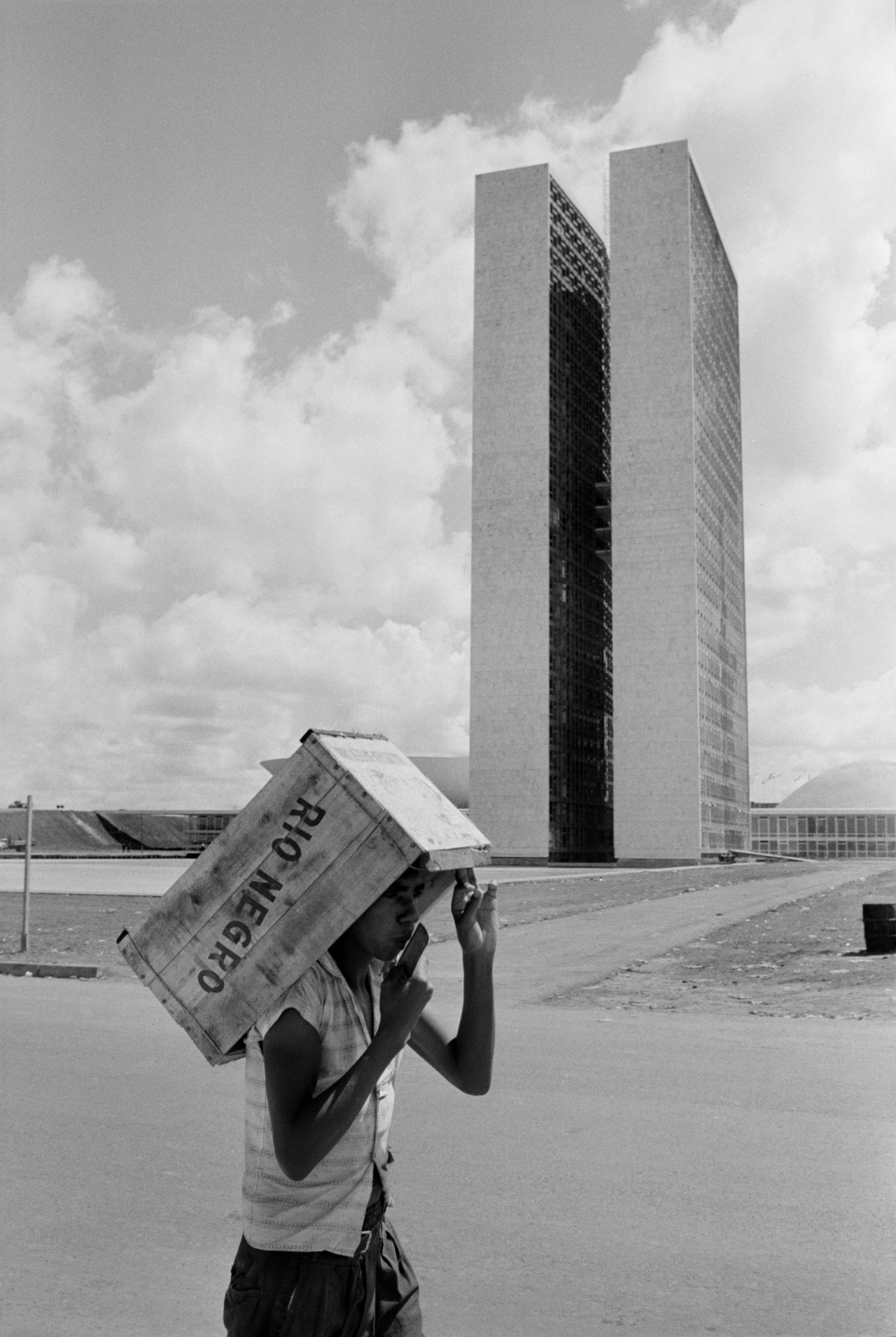

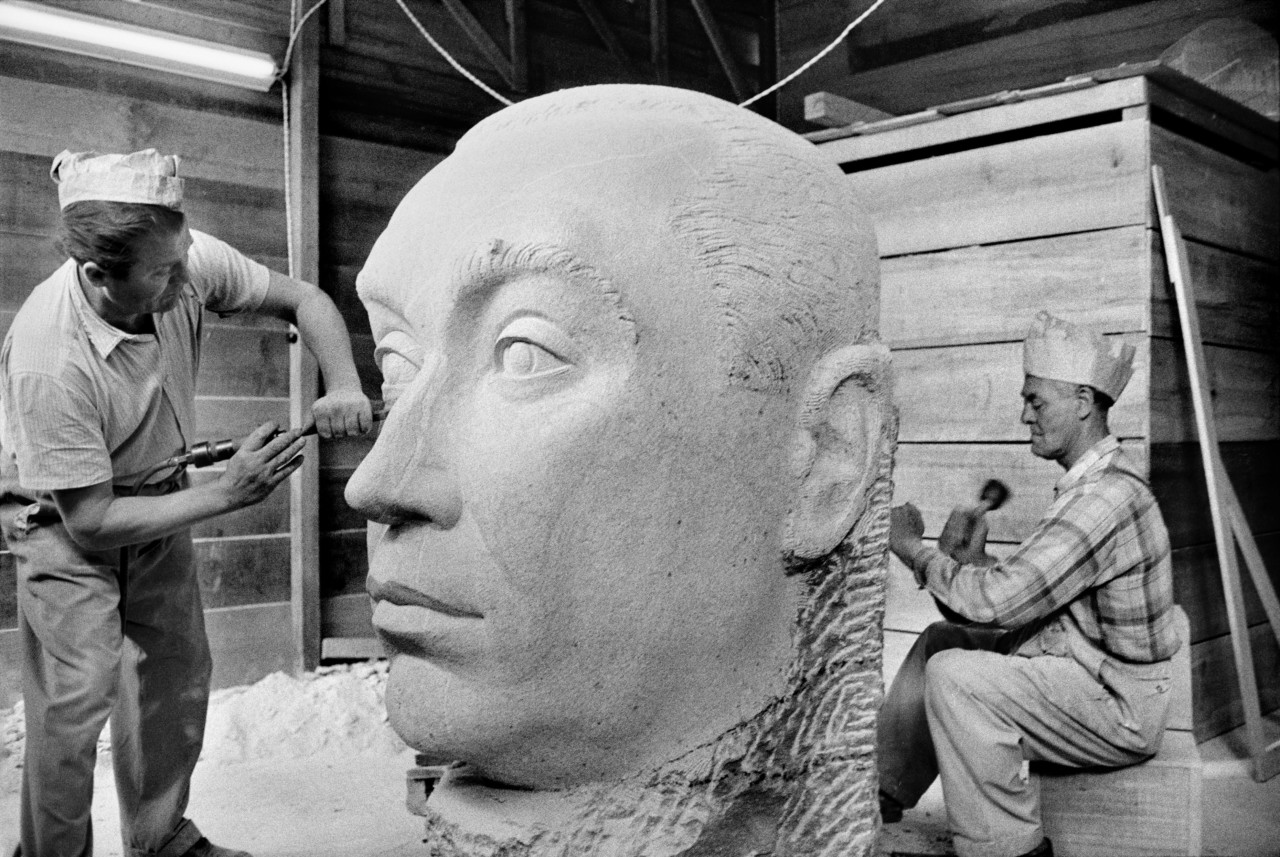

When René Burri returned to Brasilia in 1960 nearly two years after that first flying visit, he took a very different approach. His photographs never seem static, and if certain architectural forms fascinate him, then always because of the mood they generate, their inherent symbolism, or what Stanislaus von Moos in one case calls the “spectacular iconicity of Niemeyer’s monumental composition of the Assembly and the Secretariat buildings as revealed … in a famous shot by René Burri”. Symbolism was part of Brasilia’s history right from the start, but symbolism alone was nothing without monumentality, sentimentality, and kitsch. Burri was not afraid of turning the spotlight on this explosive combination and captured it above all in his superb color photographs. What fascinated him most, however, even in Brasilia, was still the comédie humaine. Endowed with the open-mindedness and impartiality of a typical cub reporter, he painted for himself a portrait of a city in the process of becoming: He photographed the workers in the colorful Cidade Livre and in the red dust of the construction site; he snapped the president, the architects, and the diplomats installed in their new quarters; he immortalized the indigenous peoples who had been driven off their ancestral lands and the families of the construction workers on a visit to the finished buildings; he recorded both the humdrum routine of an ordinary working day in the city’s schools and hospitals and the festivities of April 21st, 1960, complete with the motor racing and the air show. Only for the superquadras did he content himself with aerial shots alone; in his eyes the International Style of the apartment blocks was a reflection of the comparatively unspecific lives of those who inhabited them. Thus Burri succeeded as had no other in conveying “the vibrations of life” that characterized the early days of Brasilia. Unlike Ernst Scheidegger – and recently Bärbel Högner – whose Chandigarh cycle is likewise full of scenes of everyday life, Burri did not have an ethnographic agenda. Nor did he have ambitions of doing what Iwan Baan recently set out to do, namely to record “how people are living, thriving, or coping with Modernism” And he certainly did not use these exciting new buildings merely as a stage set for a “story” in the way that Philippe de Broca did when he sent Jean-Paul Belmondo on a wild chase through the government buildings in L’homme de Rio – although a chase is hard to beat when it comes to making the magic of architecture in the round an almost palpable experience. Burri’s concern was rather to package complex processes and significant events in fascinating pictorial dispatches whose message went far beyond the actual occasion for sending them.

"Among the innovations here were Burri's aerial shots of small fragments of the city, which at times look like abstract compositions and at times like crystals or biological matter seen under the microscope"

-

Burri was at last granted full membership of Magnum in 1959. Most of his 3,000 negatives on the life and works of Niemeyer’s great mentor Le Corbusier were shot that same year and the year following: the result was a series of extraordinary, quasi-filmic sequences showing archetypal situations in the life of the great architect. There can be no doubt that Burri was now at the height of his powers. He was also “leading a double life” in the sense that alongside his black-and-white camera, he now armed himself with one loaded with color film as well. At first he simply took two versions of the same picture, but he soon learned how to exploit the potential of color photography to the full. While the aforementioned “El Gaucho” special for Du lives from the magisterial rhythm of its black-and-white images, his photo report on Le Corbusier that was likewise published in Du in 1961 is essentially a sequence of both black- and-white and color photographs, neither of which is given prominence over the other. But in “Brasilia,” the report published in Paris Match of May 28th, 1960, the black-and-white images are no more than bookends with five double pages of spectacular color photographs sandwiched between them. Brasilia’s cinemascope-like scenery with its red earth, unnaturally blue sky, and dramatic cumulus clouds was of course ideal material for the large and glossy magazines. Yet it showcased only one of the many genres which Burri, his eyes now calibrated for color, was then exploring. The fifteen pages of color photographs which Burri shot in 1977 for the Brazilian magazine Manchete read like a textbook account of alternative approaches to photography. Among the innovations here were Burri’s aerial shots of small fragments of the city, which at times look like abstract compositions and at times like crystals or biological matter seen under the microscope. The colorful scenes from the sectarian milieu of the Vale do Amanhecer date from as recently as 1997, as do the magical twilight images of the Las Vegas-like neon facades of the shopping center and of a disk-like sun disappearing behind the Eixo Monumental. Burri defined the mission underlying his work with the camera very early on in his career: “The enormous social upheavals of our technical age are changing the face of contemporary man. My task is to trace this development and to reflect on it in my images,” wrote the twenty-five-year-old Burri in “El Gaucho.” As an inquiring art photographer, moreover, he was equally interested in exploring, and constantly adding to, his own expressive palette. Color was one such addition, though he has also ventured into the terrain of film, and in recent years has produced more and more collages, many of which recycle fragments of his own work. The new Brazilian capital in the process of becoming supplied him with the raw material he needed for a story of truly epic breadth. And if he continued working with this material for years to come, then not only because it reflected so perfectly his own personal interests, but also because it had proved such fertile soil for cultivating an artistic style of his own.