Trent Parke’s Monument to Life on Earth

In the Australian's latest book, images of light battle dark in a dystopian vision of humankind. Interview by Colin Pantall.

“When I moved to Sydney, my first real impression was the sheer volume of people and the endless procession of city workers making their way to and from it,” writes Trent Parke in his overview of his epic new photobook, published this summer.

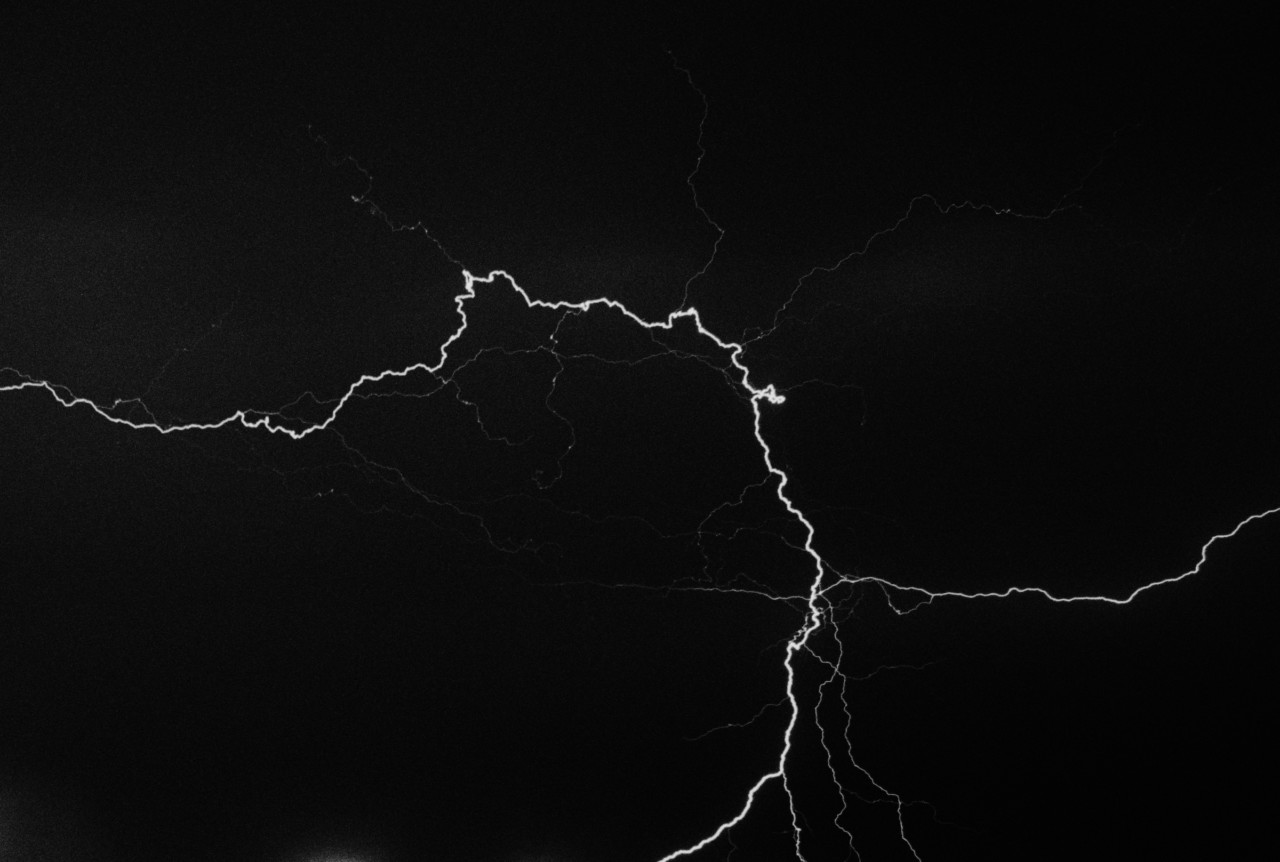

Monument is a book with a narrative in which the earth is approached from space; in which the futility of our existence is laid against the inevitability of our impending demise. It’s a book where images of light battle dark — a dystopian vision that owes as much to the science fiction films Parke watched in his youth as it does to the magical photographic experiments he undertook in Sydney two decades ago.

Here, in Australia’s biggest city, Parke worked the streets, moving with the flow of people, increasing his photographic intensity as rush hour approached. He became one with the rhythms of the metropolis, falling in step with the commuters who massed the city’s train stations and bus stops, following the harsh Australian light that would arc down into the crevasses of the city, bouncing off tarmac and windows to light up even the darkest space.

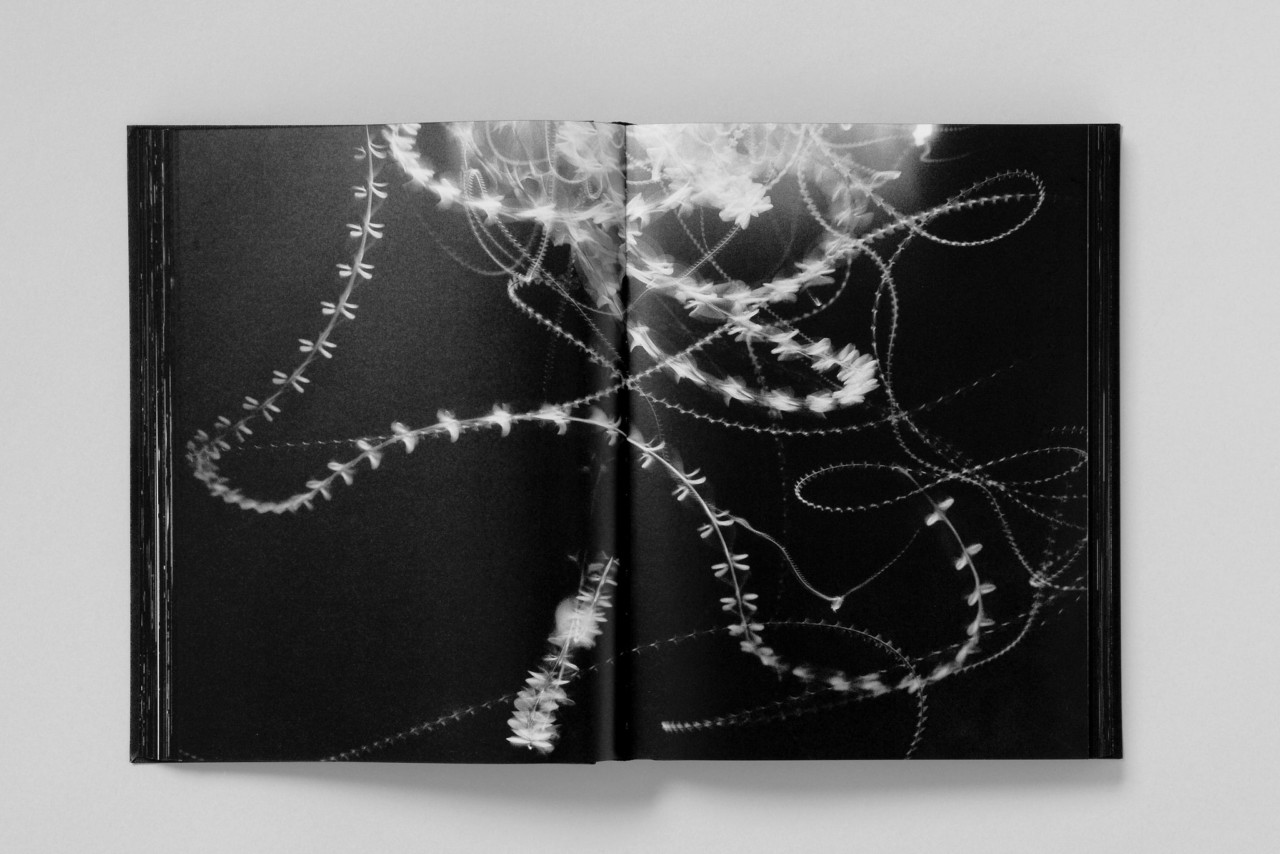

Later, after publishing his first photobook, Dream/Life, in 1999, five years after his arrival in Sydney, he took a more experimental turn, pushing the limits of what a camera can do, creating outlandish images where time, scale and perspective are skewed into a vision of Parke’s own creation. At night, he would go home to his flat and watch the moths fly over Sydney Harbour Bridge, “spiraling out of control, like small space-ships caught in a tractor beam.”

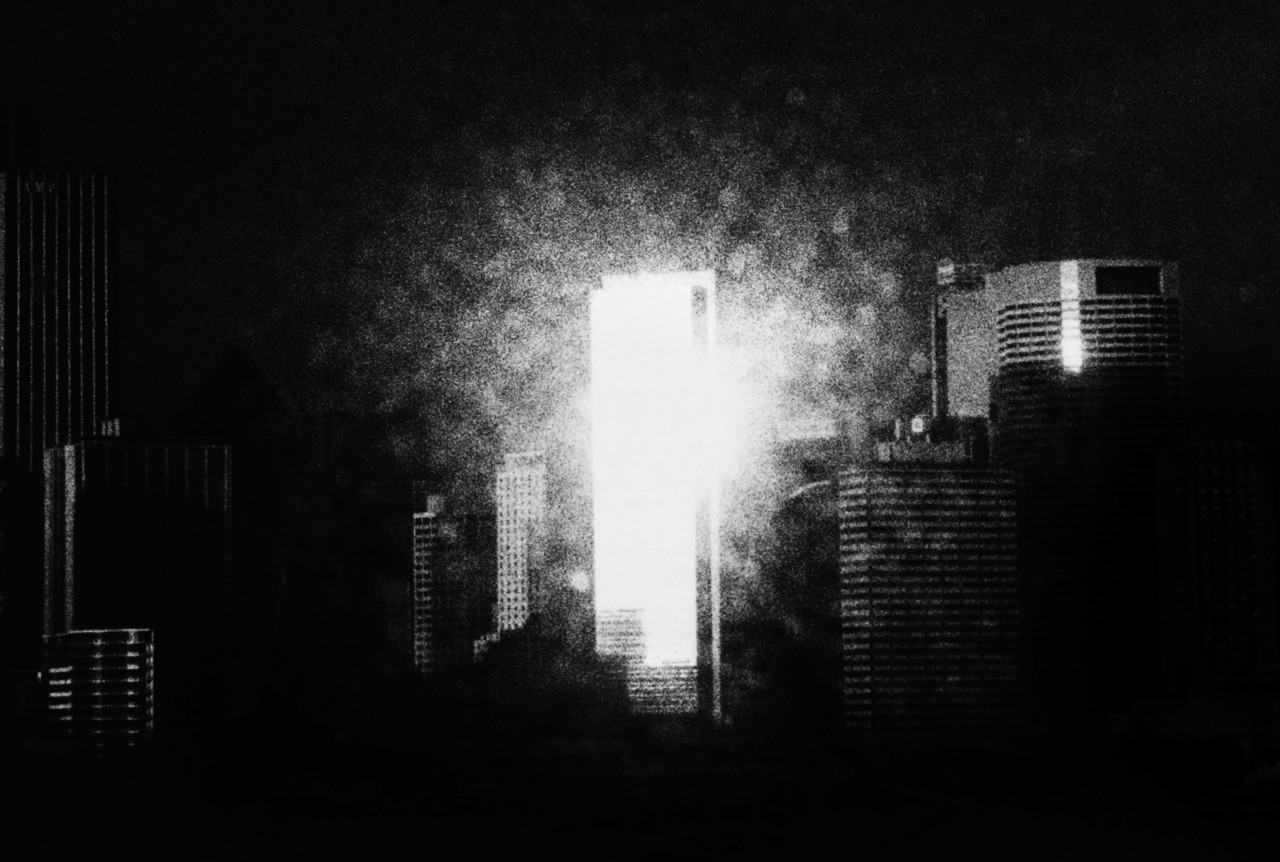

A few of these images made their way into Minutes to Midnight, Parke’s 2013 photobook, published some eight years after he and his partner, Narelle Autio, returned from their two-year, 90,000-kilometer road trip across Australia. In these pictures the city is simultaneously scalded by the sun and soaked by the rain; the end-times gathering over a country beset by firestorms and drought, in the midst of one its perennial identity crises.

But it was the whole country that Parke was looking at in this now acclaimed classic photobook in which humanity seems a guest in the natural environment, where there is a definite feeling that we are living on the surface of a planet.

"This is some of the best work that I have made... where I really became experimental and started to push the boundaries of what I was doing."

-

Year followed year, and books followed books. There was little time to reflect on past work; to look back at the thousands of images that didn’t fit.

“That’s what we do. We make the next body of work and the next exhibition and away we go,” Parke tells me from his home in Adelaide, South Australia. “We very rarely take on any commercial work, so most of the time we survive, and we only just survive, by print sales. We scrape by, but it’s always been the case where you’re onto the next thing, and the next one, and one thing leads to another and you just keep going and going and going. You never get the chance to stop.”

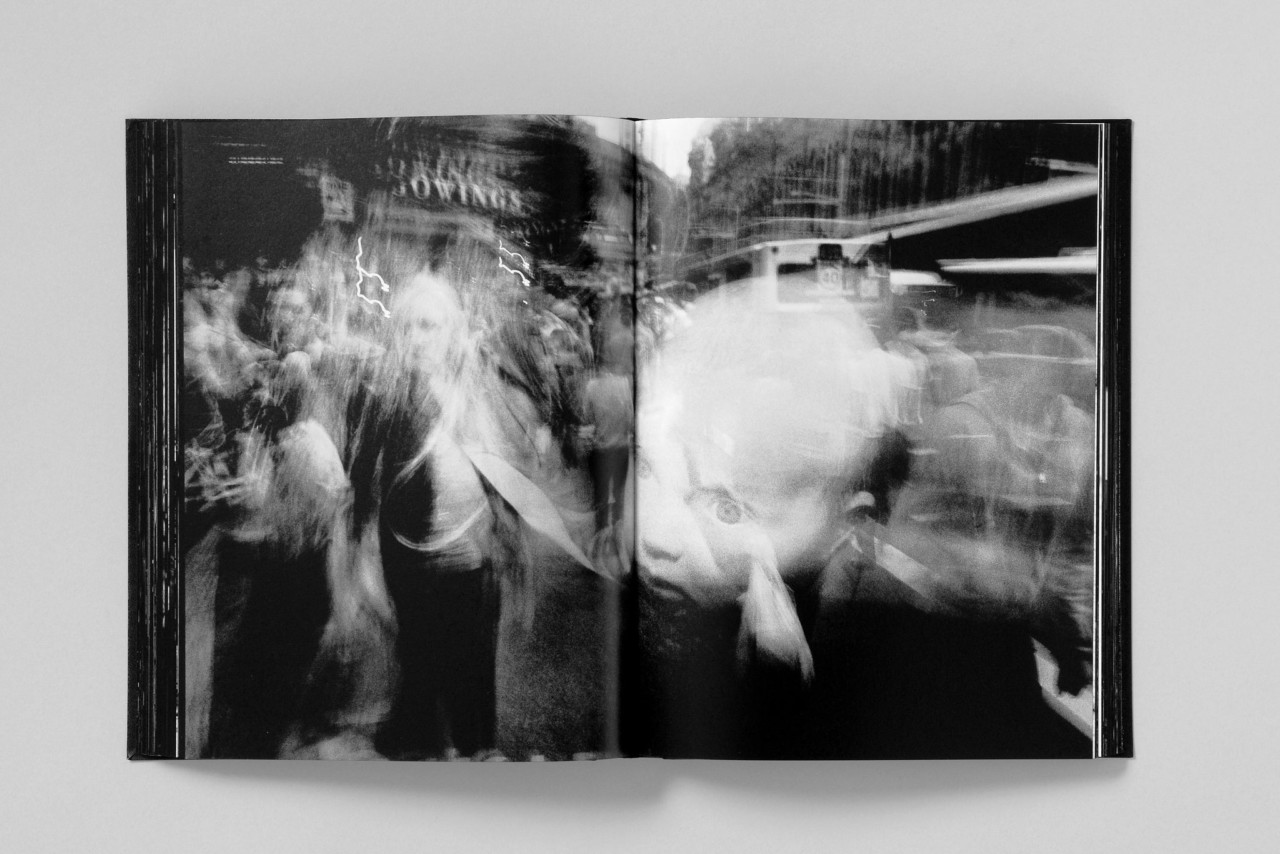

For once, he did. “I went back and started going through these negatives that are from 2000 to 2003, which is when I started shooting all this movement work on the streets of Sydney… I was like, ‘Oh my goodness, this is some of the best work that I have ever made.’ It was where I really became experimental and started to really push the boundaries of what I was doing. This is when I started to slow things down and shoot on these slow shutter speeds and really start to experiment with light, with film, with the darkroom.”

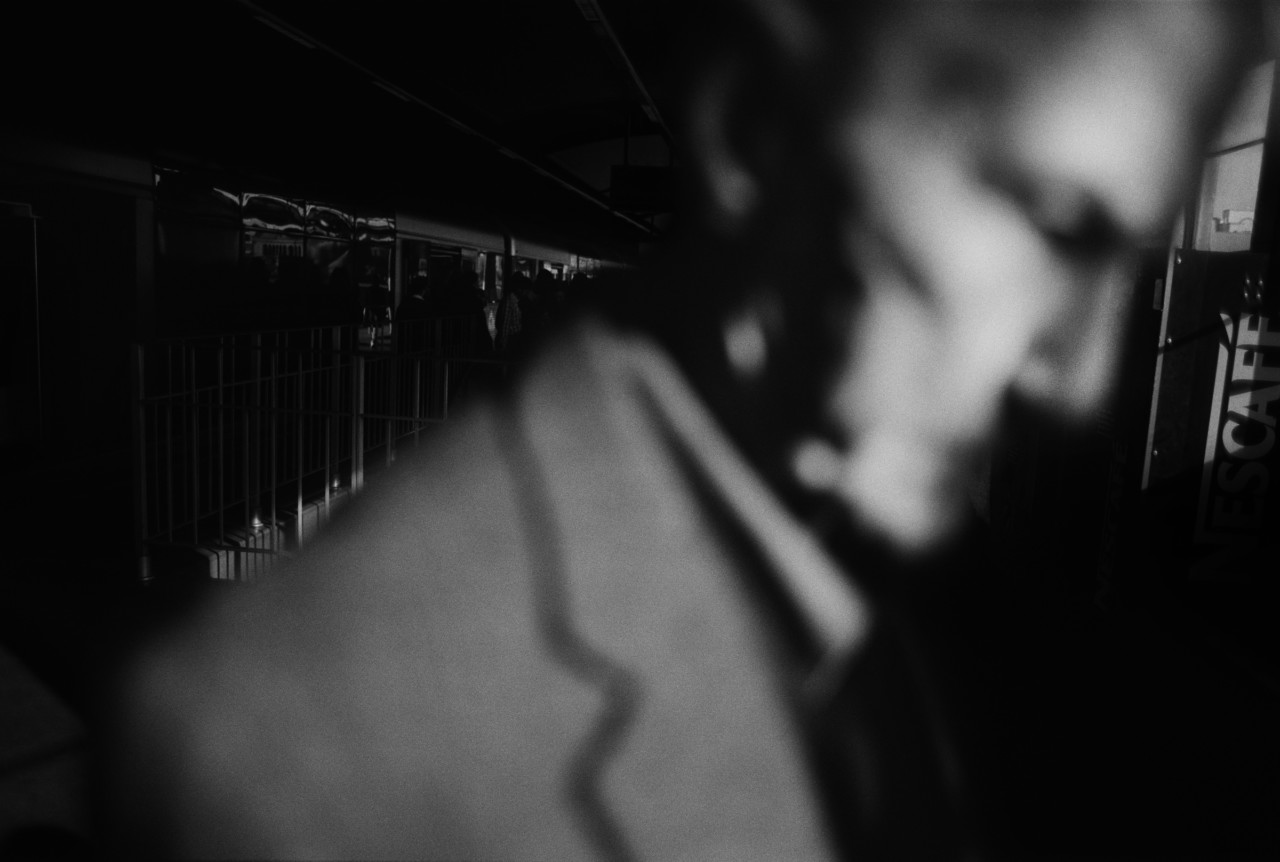

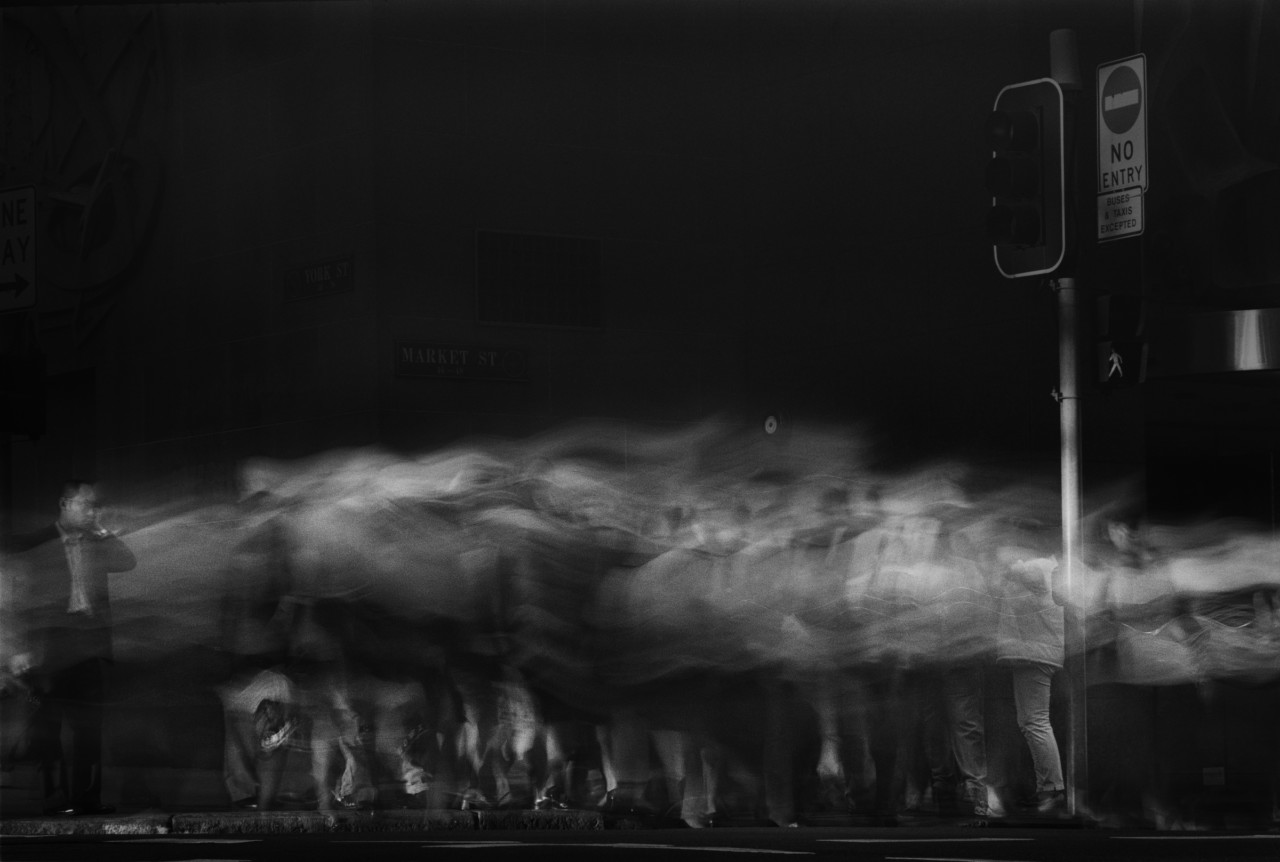

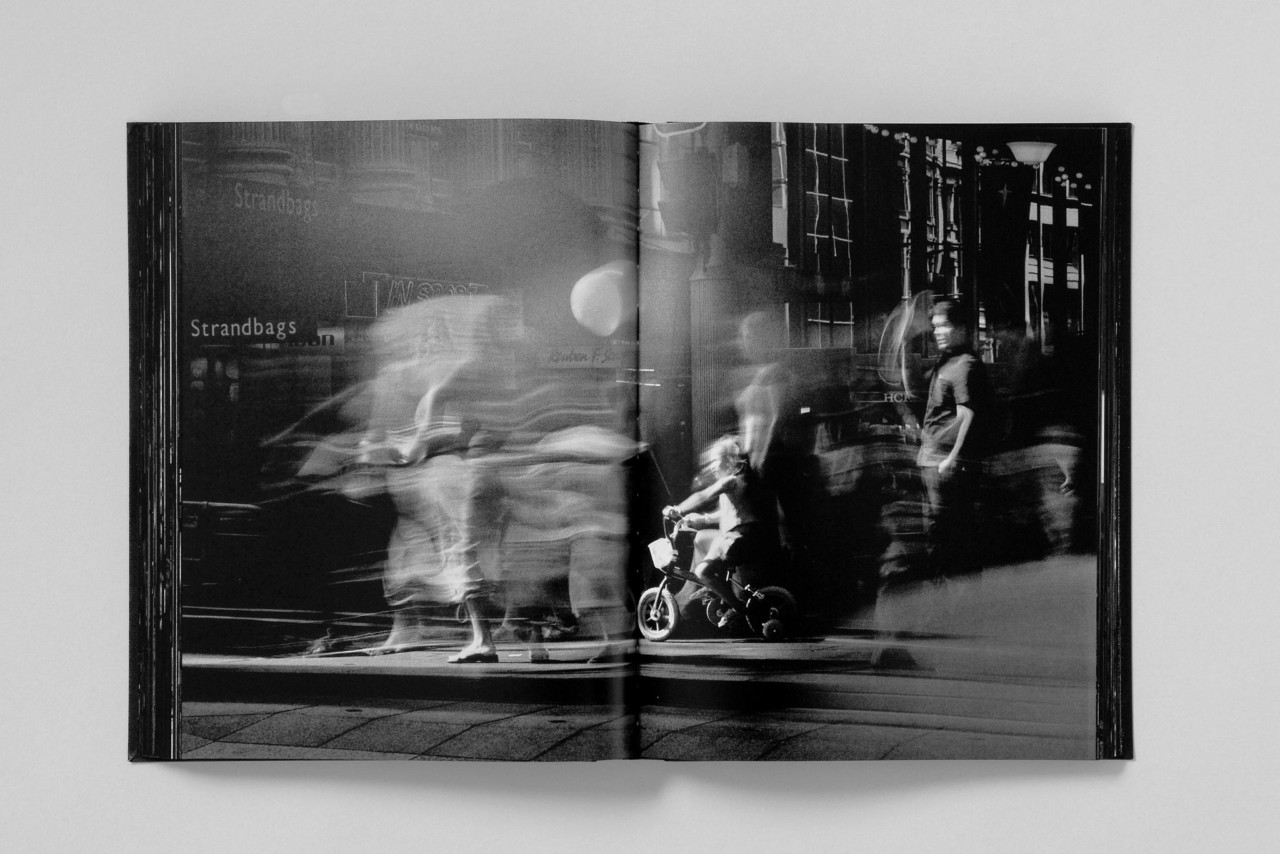

Working with different film settings, apertures, and darkroom developer concentrations, Parke increased exposure times in the Australian sun to 10 seconds, creating images that show the blurs of people drifting like ghosts through city streets. The problem was it took hours to even make one print in the darkroom.

"I’m always trying to create a fictional world in my documentary work."

-

All that work was put to one side until last year when he started scanning the negatives using a high-end Flextight scanner. What had taken hours in the darkroom took minutes on a scanner that was able to handle the blown out details. “Lots of the negs were over-exposed due to the constant experimenting, and it was only due to the hi-res scans that I started to realize that there was enough information to print them.”

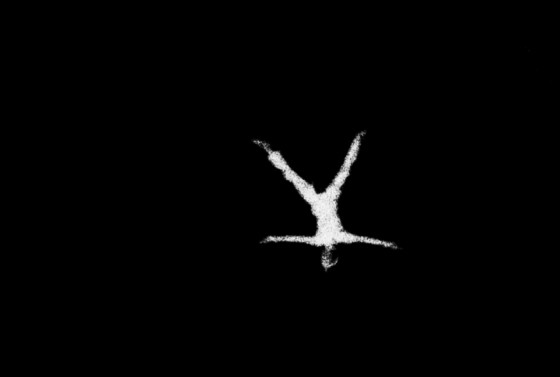

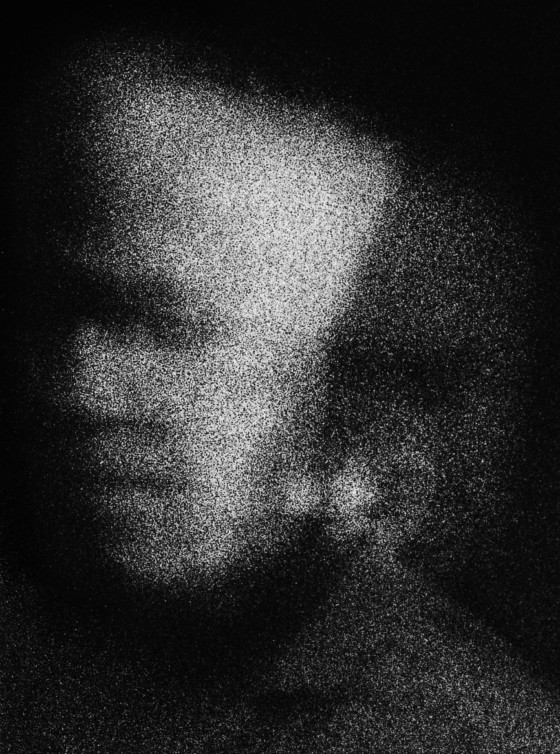

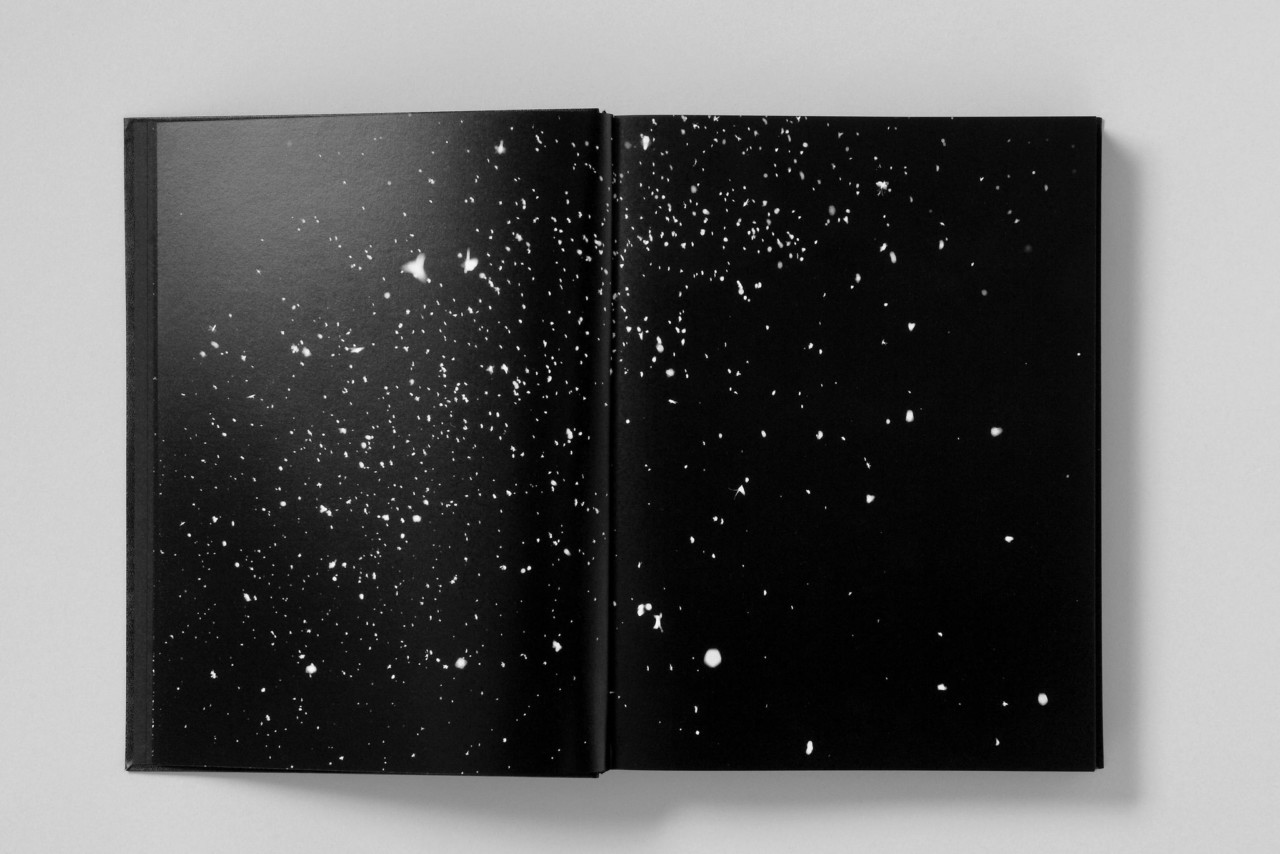

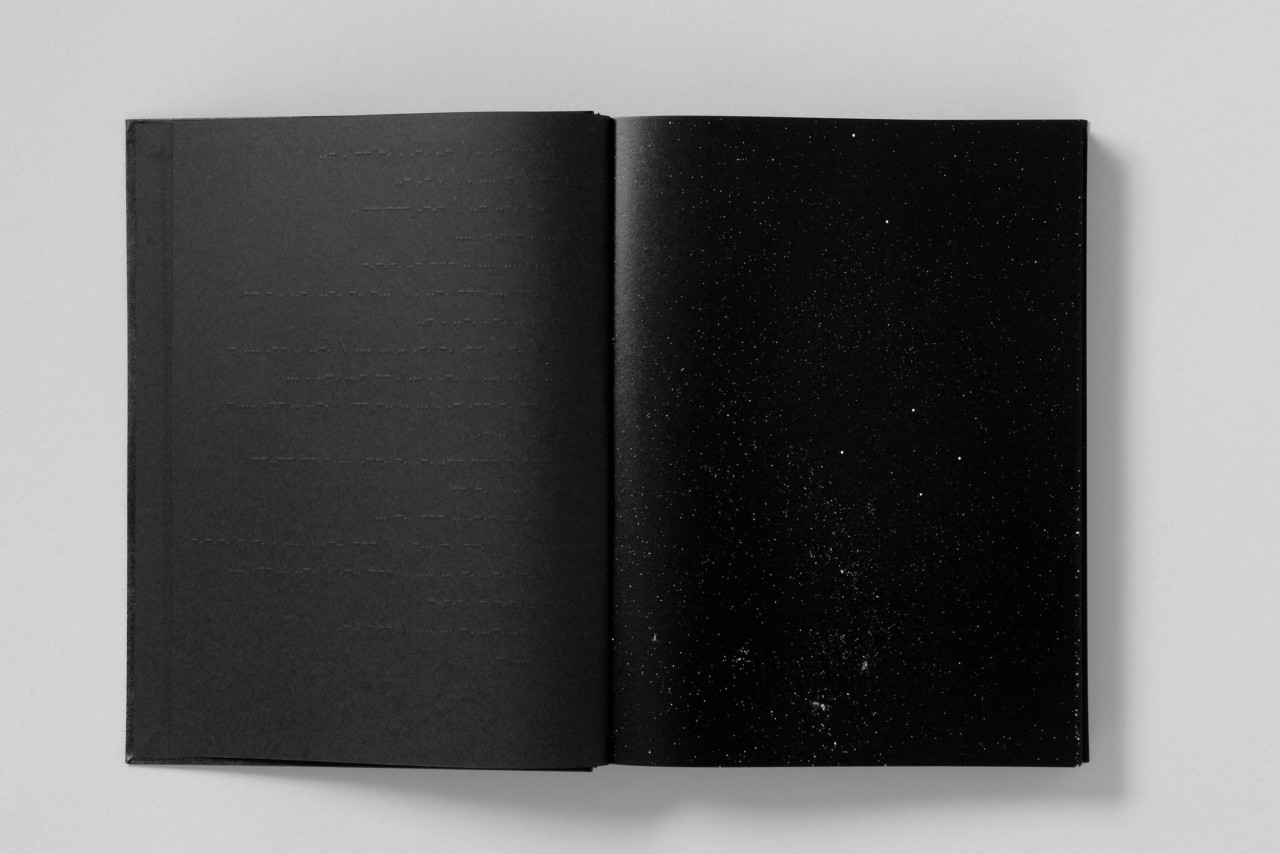

He rediscovered a tranche of work he’d never properly looked at before, and returned to other series he’d made, eventually scanning between three and four thousand negatives. They included his The Camera is God series, in which Parke photographed an Adelaide road crossing, shooting blind onto roll after roll of 35mm film, rapid-firing his shutter via a cable release. From these negatives he pulled out the tiny fragments that showed faces, blowing them up so that they lost most of their features and dissolved into a mass of star-speckled grain, fitting Parke’s conceptual framework that “…we are all just specks of dust, insects in this vast universe.”

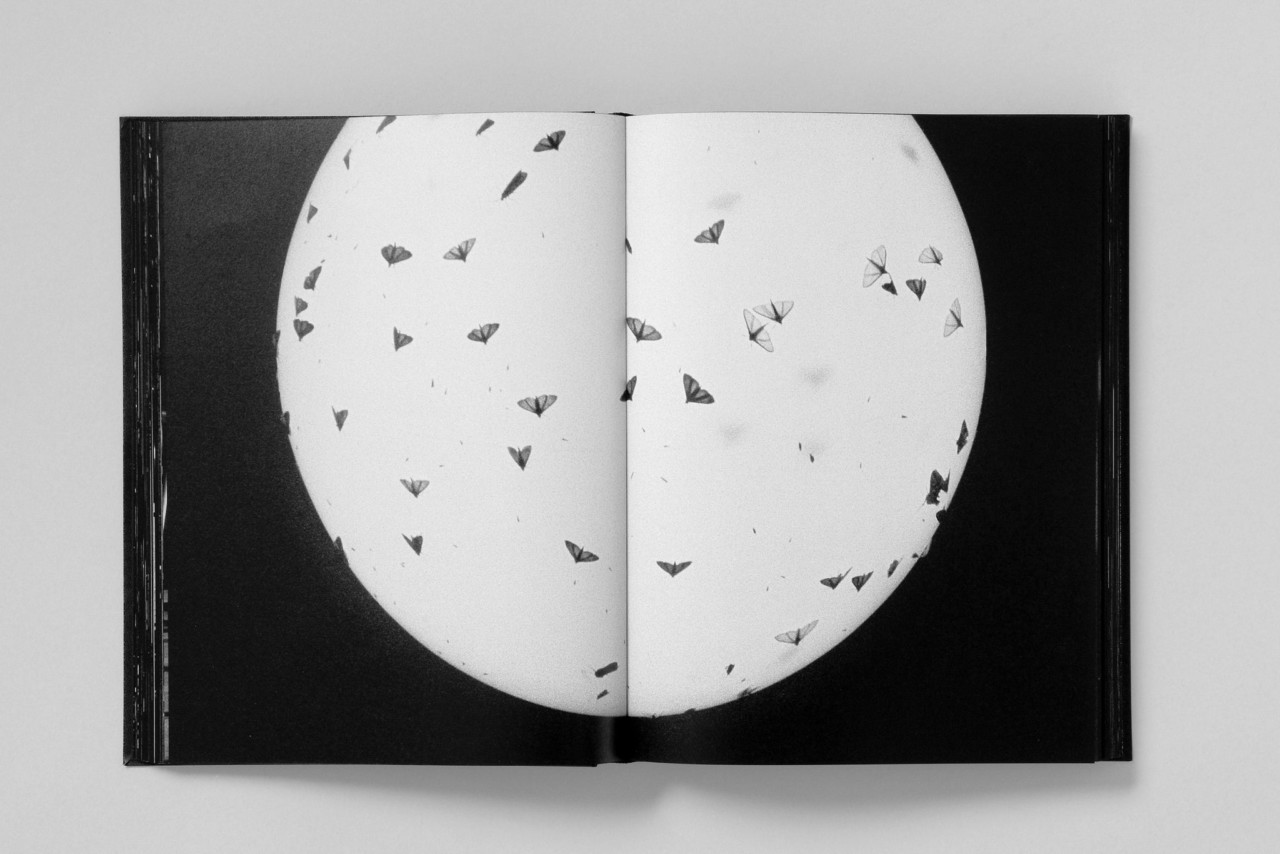

The dilemma was how to edit these together into a coherent body of work that made sense. The key to the problem was a series of pictures of moths that he had almost forgotten about and a piece of music by Max Richter.

“While I was looking through the Sydney work, I found these pictures of moths and seagulls on the Harbour bridge. I realized that I’d been photographing moths the entire time as well. The moths in a sense are a symbol of me because I’ve always been drawn to the light like the moths are to the flame. And that’s where the idea of Monument evolved from. I’m always trying to create a fictional world in my documentary work, always trying to tell a different story to the one that you actually think you’re looking at.

“In my mind it’s a film before a book, and therefore I need a soundtrack to storyboard the idea, sequence the work and create the narrative. In this case it was a score from Max Richter’s Hostiles album called Never Goodbye. By chance this music happened to be playing in the background when I first started scanning and editing the thousands of negatives for the book.

“I knew straight away that it was the feeling I was looking for. I wanted something that started off very simple but had that feeling of melancholy, before spiraling out of control to eventually end up the same way that it started. It’s the human race as a blip in the life of the universe spanning the dawn of time.”

"We are all just specks of dust — insects in this vast universe."

-

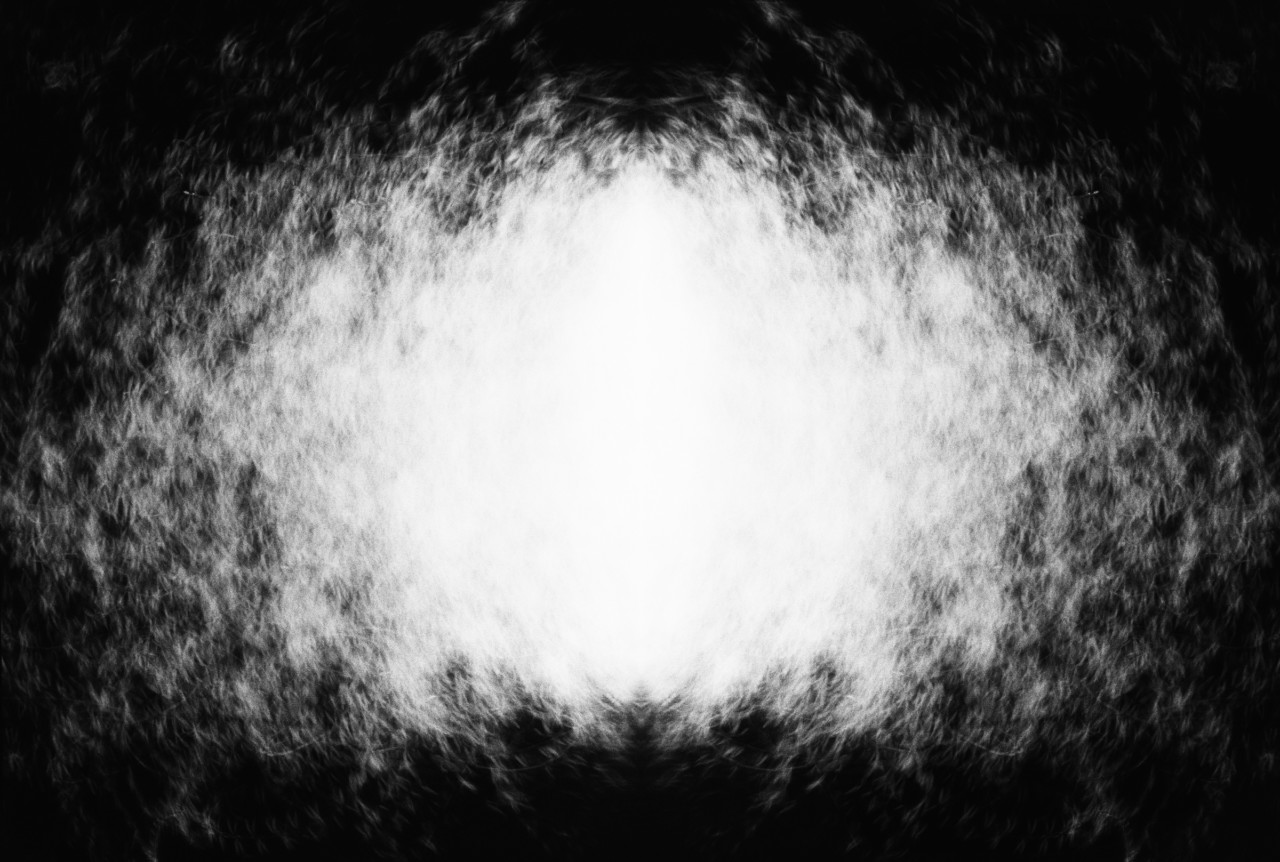

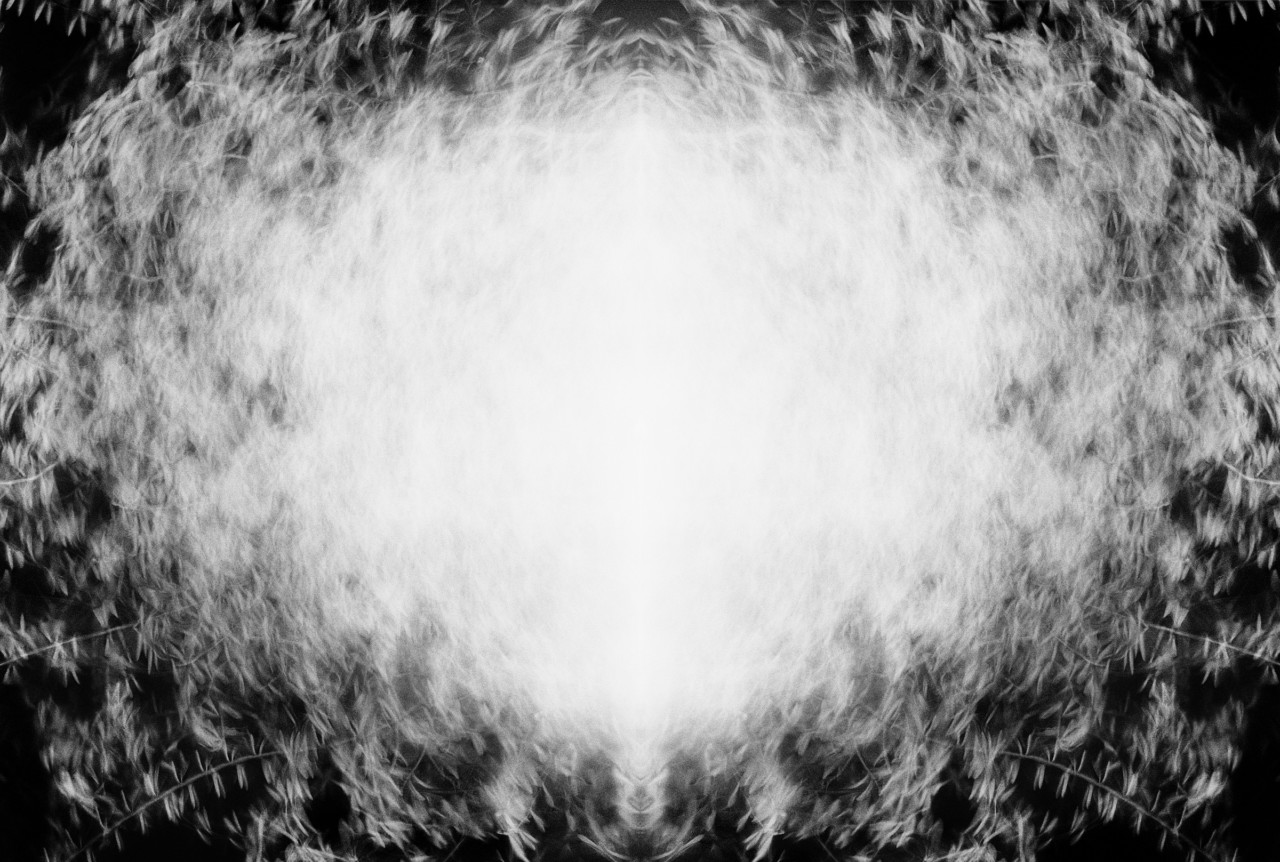

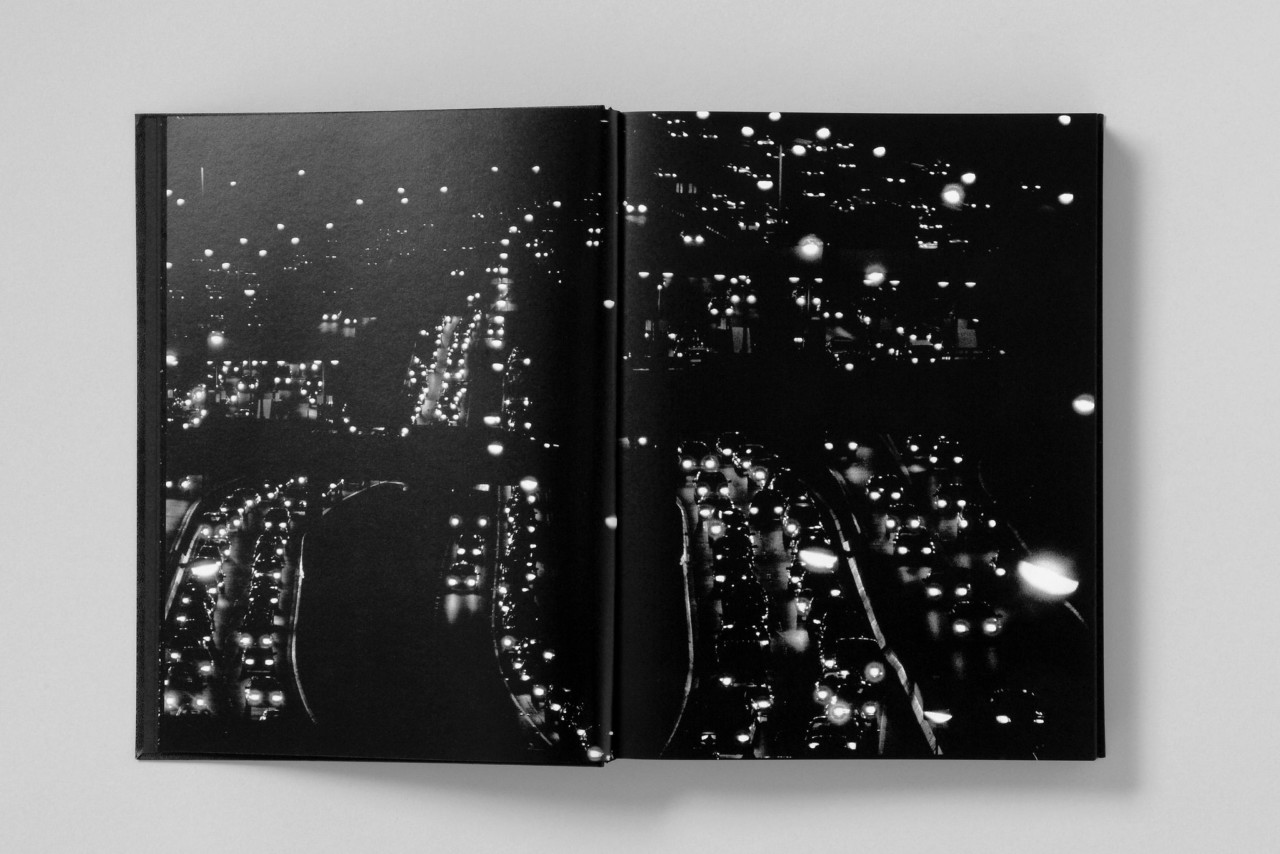

The book begins with the moths. They appear as glowing, star-like specks, vague shapes that gradually come into being as they trail across the Sydney night sky. The moths are the entry point to the world, and gradually they morph into the lights of the highway, the lights of city streets, and the idea that we are all part of this same planet and that our time on this earth is limited.

Then we move to the city, a dark metropolis delineated by light and shade. People emerge from the shadows, walk into clouds of steam, rush through shafts of light and darkness, disappear into chasms of concrete, and carry the weight of the world upon their shoulders.

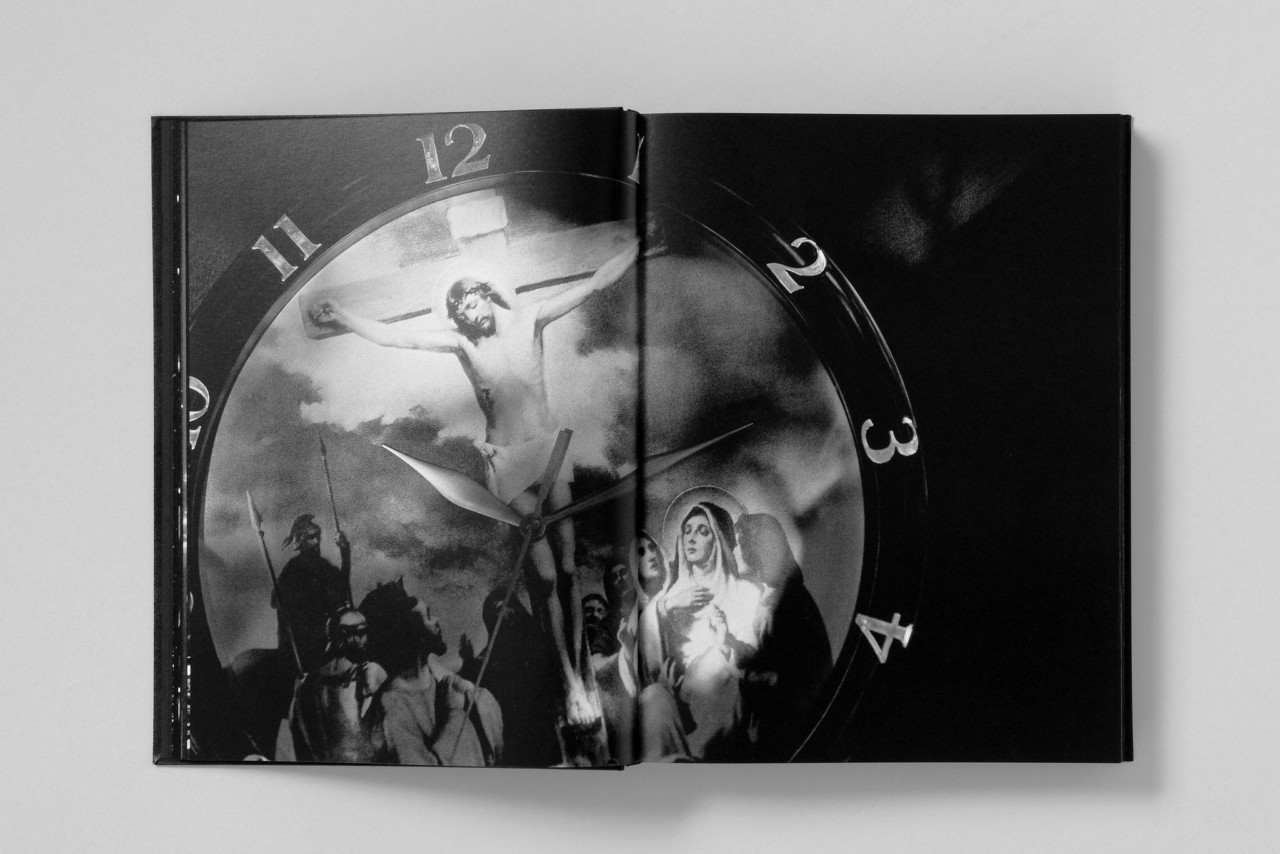

Homeless people mix with commuters; a man wears a crown of thorns; isolated figures seek out single pillars of light; and then the moths return, swirling masses of them that make corkscrew shapes in the sky, the DNA of our existence.

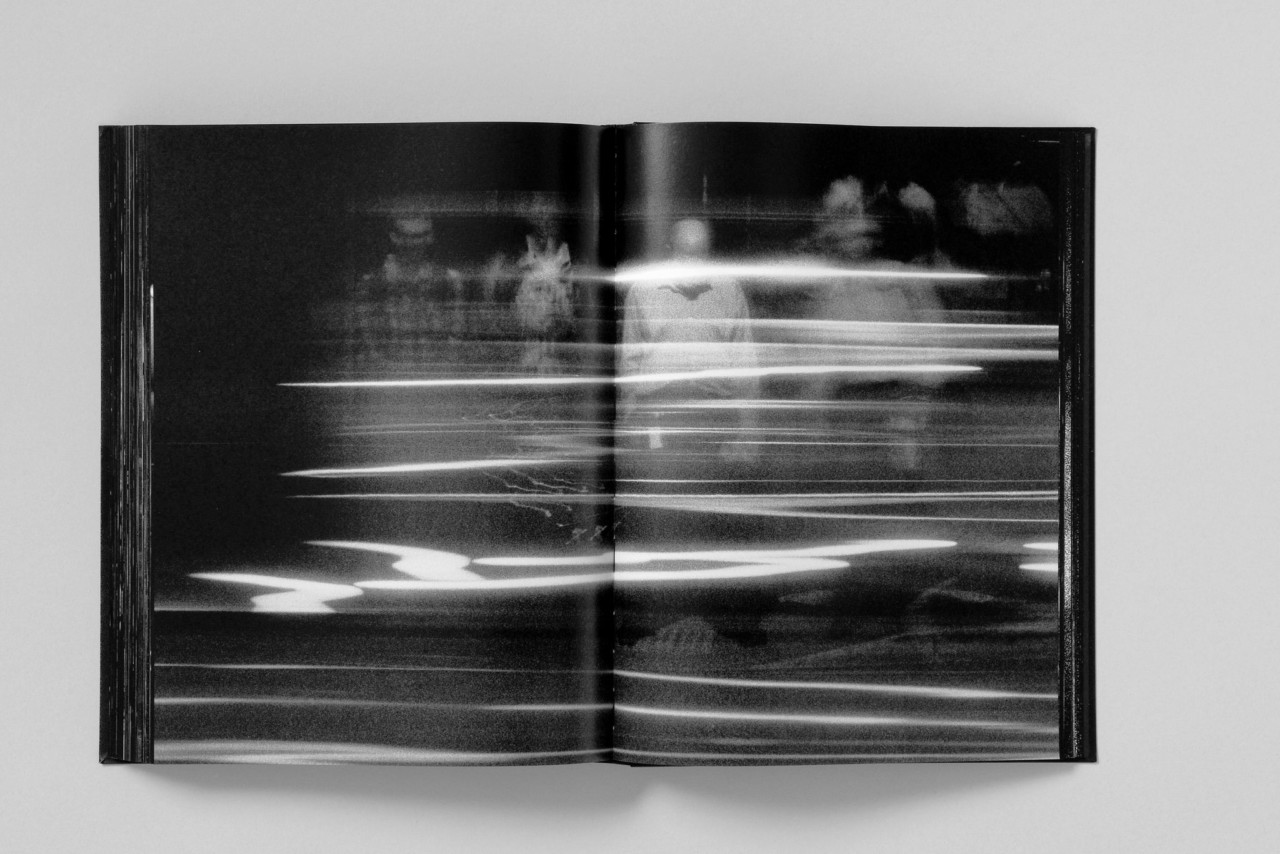

And then the light returns, blazing sheets of light that scorch the earth, light that people, just like moths, can’t help but walk towards. It’s an explosion of light made with long exposures that create a ghost world through which figures drift and fade.

A few of Parke’s most iconic images from Minutes to Midnight appear; the shadows of pedestrians set against the ghost-image of the bus, the stop light in the blast of rain, the workers on George Street. Time slows down, movement decelerates, and scale enters another dimension as the populace finds itself stretched and distorted across the face of the silver emulsion.

The fragmentation continues as bodies, faces and limbs disintegrate into the grain. And then finally we’re back where we started, in a starscape, a constellation made up of fragments of humanity. Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, with no hope of resurrection to eternal life, the book ends.

"I started to slow things down and shoot on these slow shutter speeds and experiment with light, with film, with the darkroom."

-

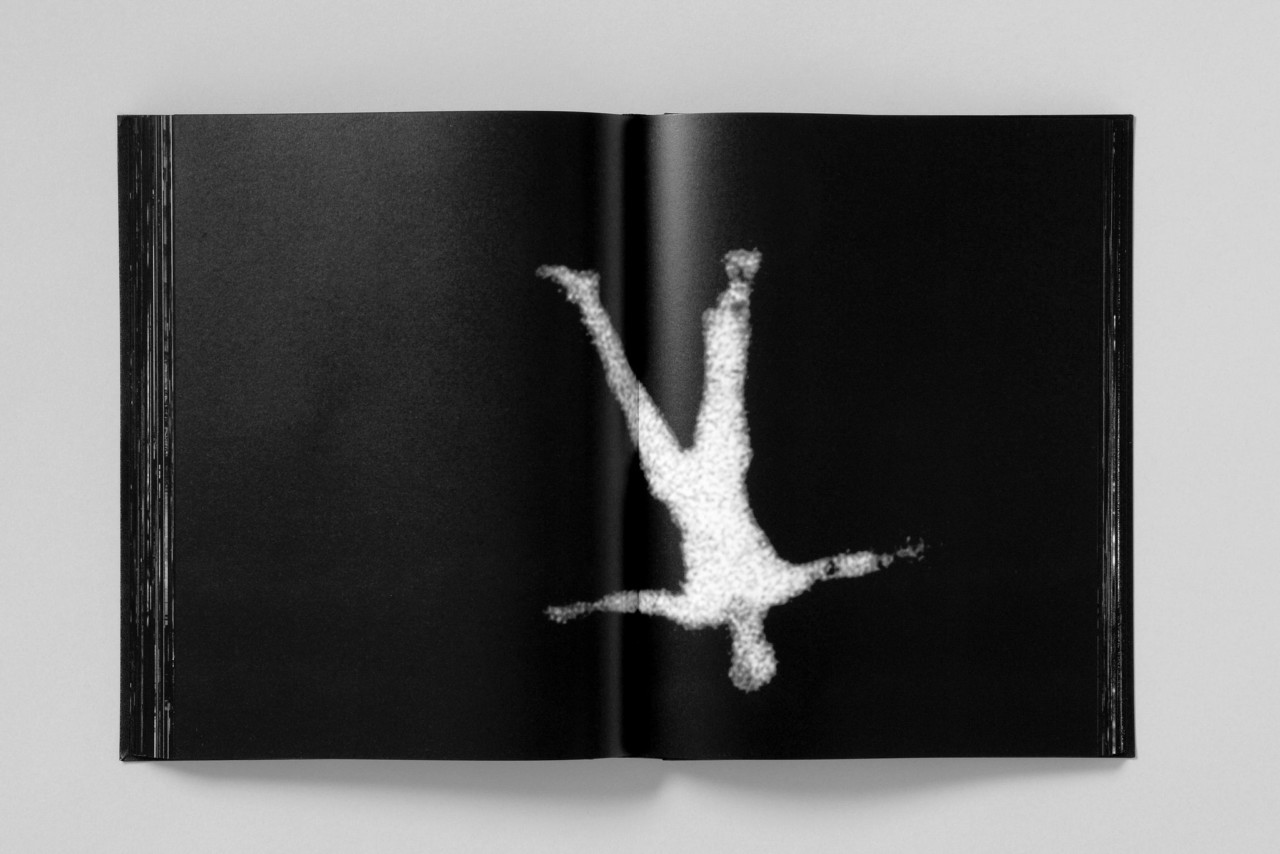

Throughout the book, a single finger keeps repeating, a man apparently in freefall silhouetted against the Sydney sky. “He’s a symbol of what’s left of the human race after the world is over,” says Parke. “He tumbles through the book, he’s like my falling star, in eternal blackness forever and ever.”

It’s a dystopian book, but one in keeping both with Australia’s geographical otherness — a place where the prospect of a long drawn-out death to global heating is in clear sight. And it’s a world view based on Parke’s life experience.

“I’ve always felt (as a lot of photographers do) like I’m on the outside. It’s as if I’m looking at humans from space, where you’re removed from everything, and you’re looking at the world, what it is, your place in it, and how we came to be here, and what’s going to happen next.

“I think for me it’s always trying to find the surreal in the ordinary. I think the formative years in your childhood are the most important. My mum died when I was quite young and it was a pretty traumatic experience because I was with her at the time, and from that point on, nothing’s ever the same. You’re continually questioning life, and death is never far away from my thoughts. On a daily basis you are thinking about it because at the end, what else is there?”

"This is my record. This is my time capsule of what it was like to live in my lifetime. This is my monument of humankind."

-

The use of stars as a metaphor for the essential insignificance of our existence also have a link to Parke’s personal history and photographic development, in particular the time he spent in the bush with his partner, Narelle Autio, making some of the photographs that appeared in the book

“I think sleeping in a two-man tent like we did for two years out in the Outback influenced me. You’re alone with the stars. We went for months while we were out in the bush without seeing another person or a car or a cloud in the sky. That was the thing. Not seeing a cloud for three months in the winter. It’s just blue, blue, blue, blue. A cloud is an amazing thing when you see it for the first time after a long time.”

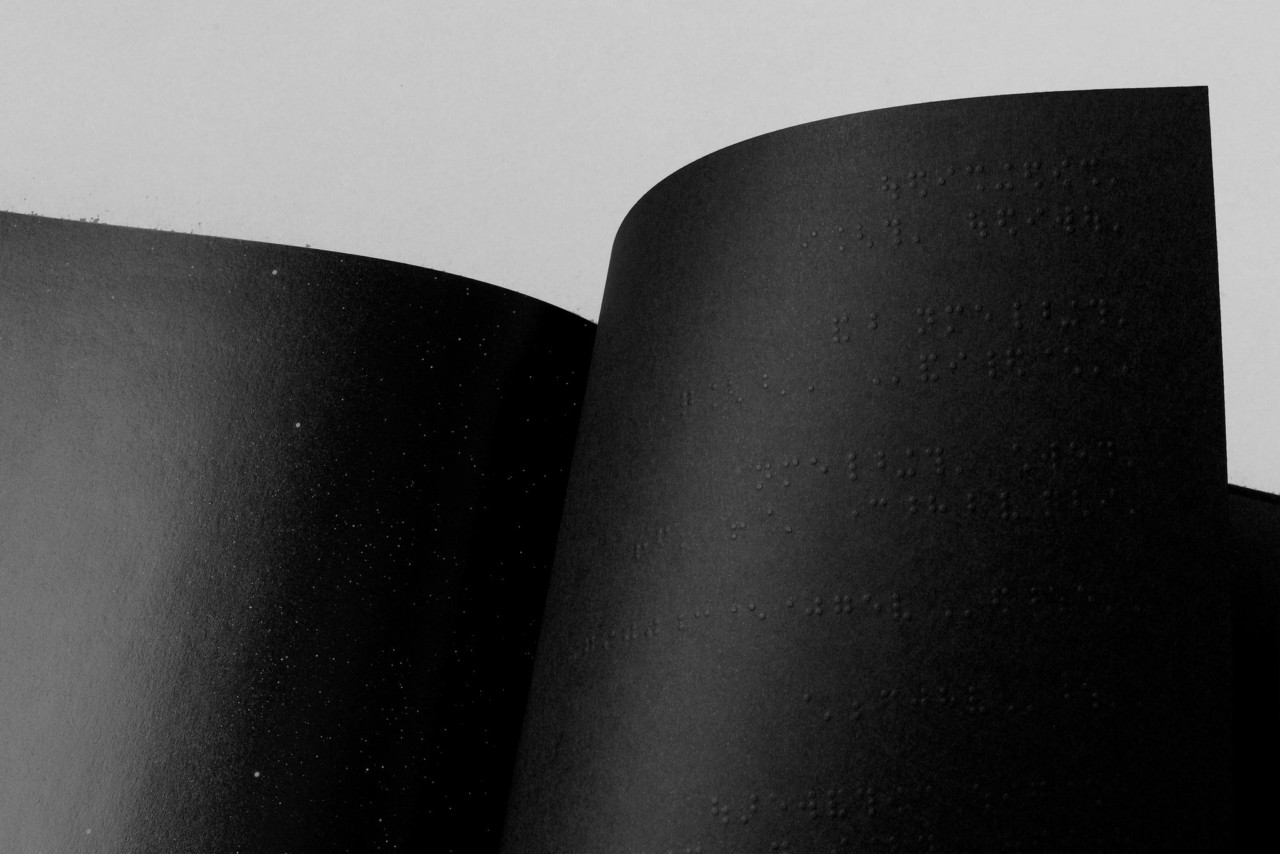

The cover of the book is a take on the Golden Record that accompanied NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, “…a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.”

“I find it absolutely fascinating that in 1977, they sent these golden records into space for intelligent extraterrestrial life to find,” he says. “This is my record. This is my time capsule of what it was like to live in my lifetime. This is my monument of humankind.”

Trent Parke’s Monument is published this July by Stanley/Barker, and is available in the Magnum Shop here.

The Magnum Shop’s Trent Parke Collection includes books, posters, contact sheet prints, and a limited edition print of one of the photographs that appears in Monument.