Humanism, Magnum, and the Family of Man

Alona Pardo, photography curator of The Barbican Gallery, on the blockbuster show and the unifying 'perspective of solidarity'

The following article is adapted from a presentation given by Alona Pardo as part of The Medium is the Message symposium, on June 26, 2019 at London’s Barbican Center. The presentation preceded a discussion, chaired by Pardo and featuring Magnum photographers Olivia Arthur and Peter van Agtmael, on the topic of humanism in contemporary photographic practice.

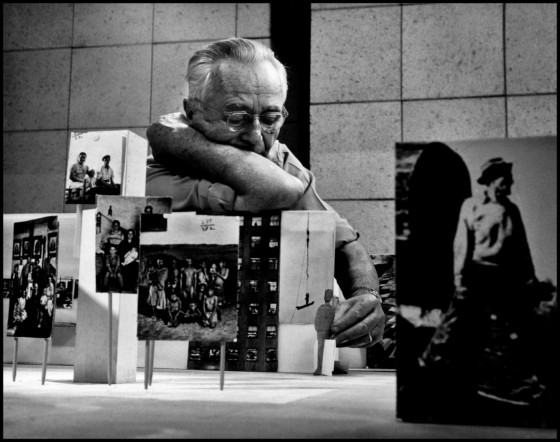

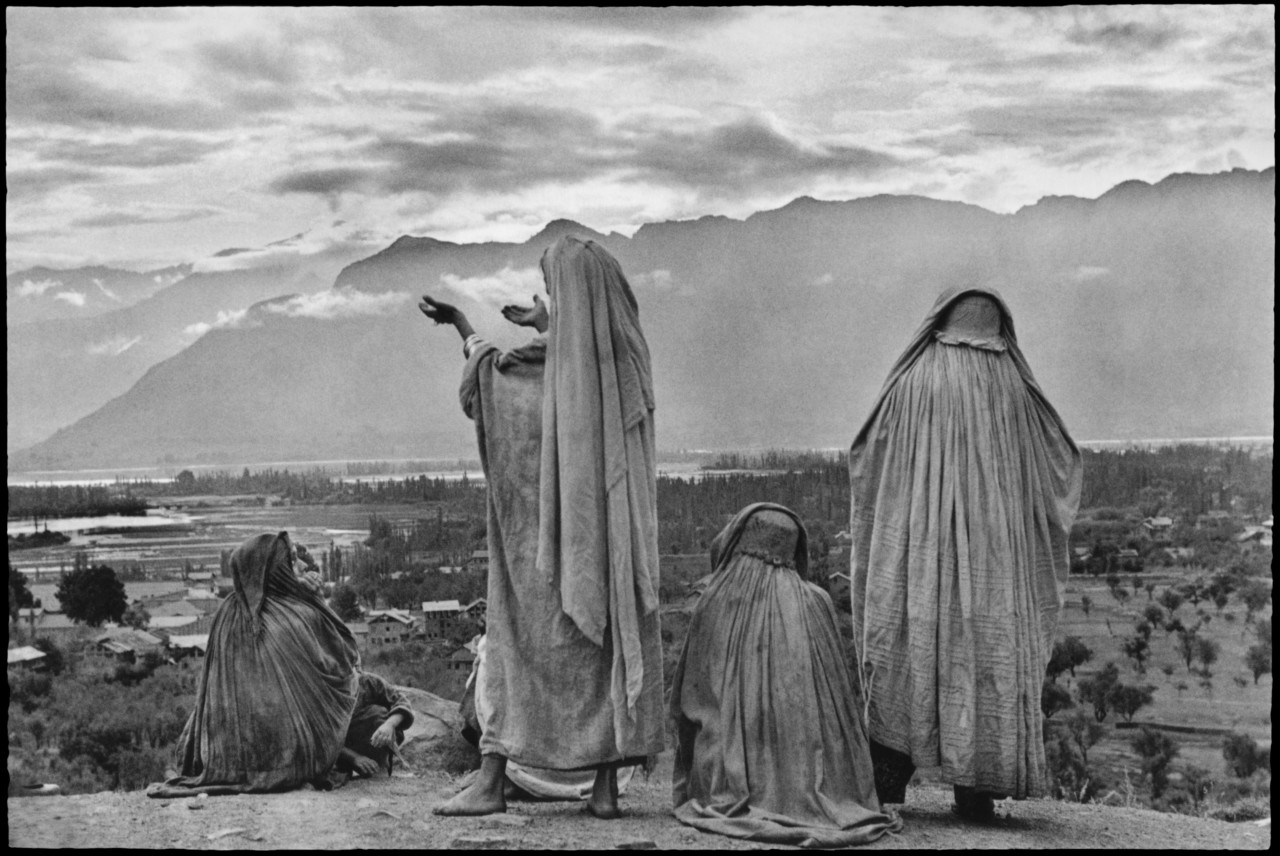

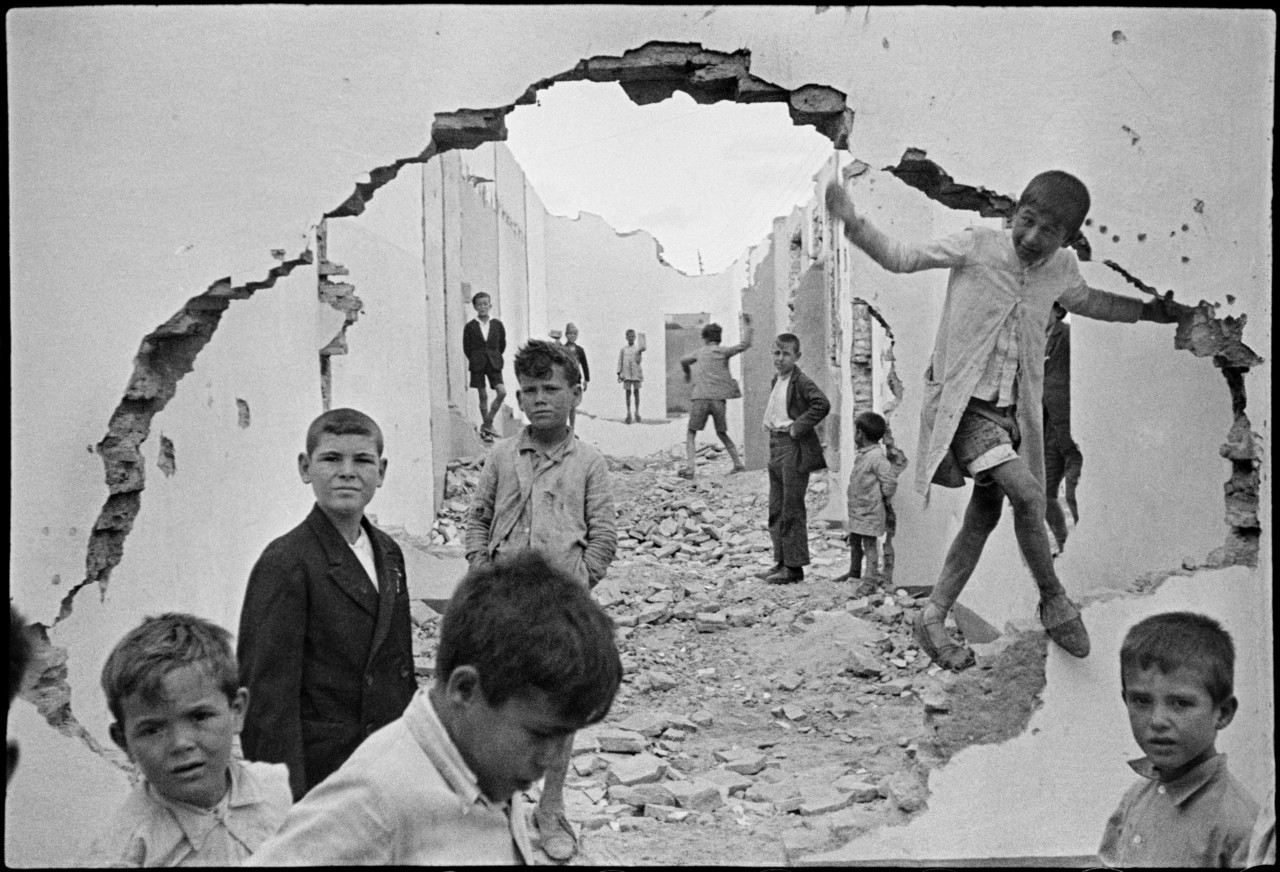

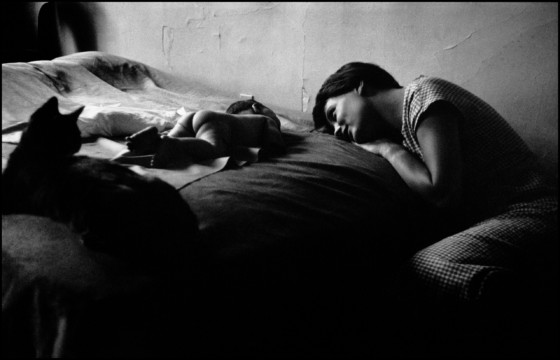

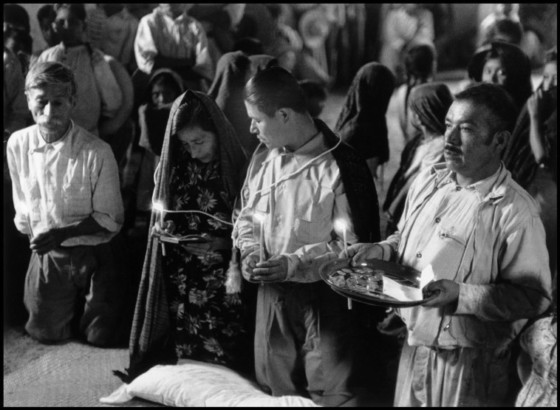

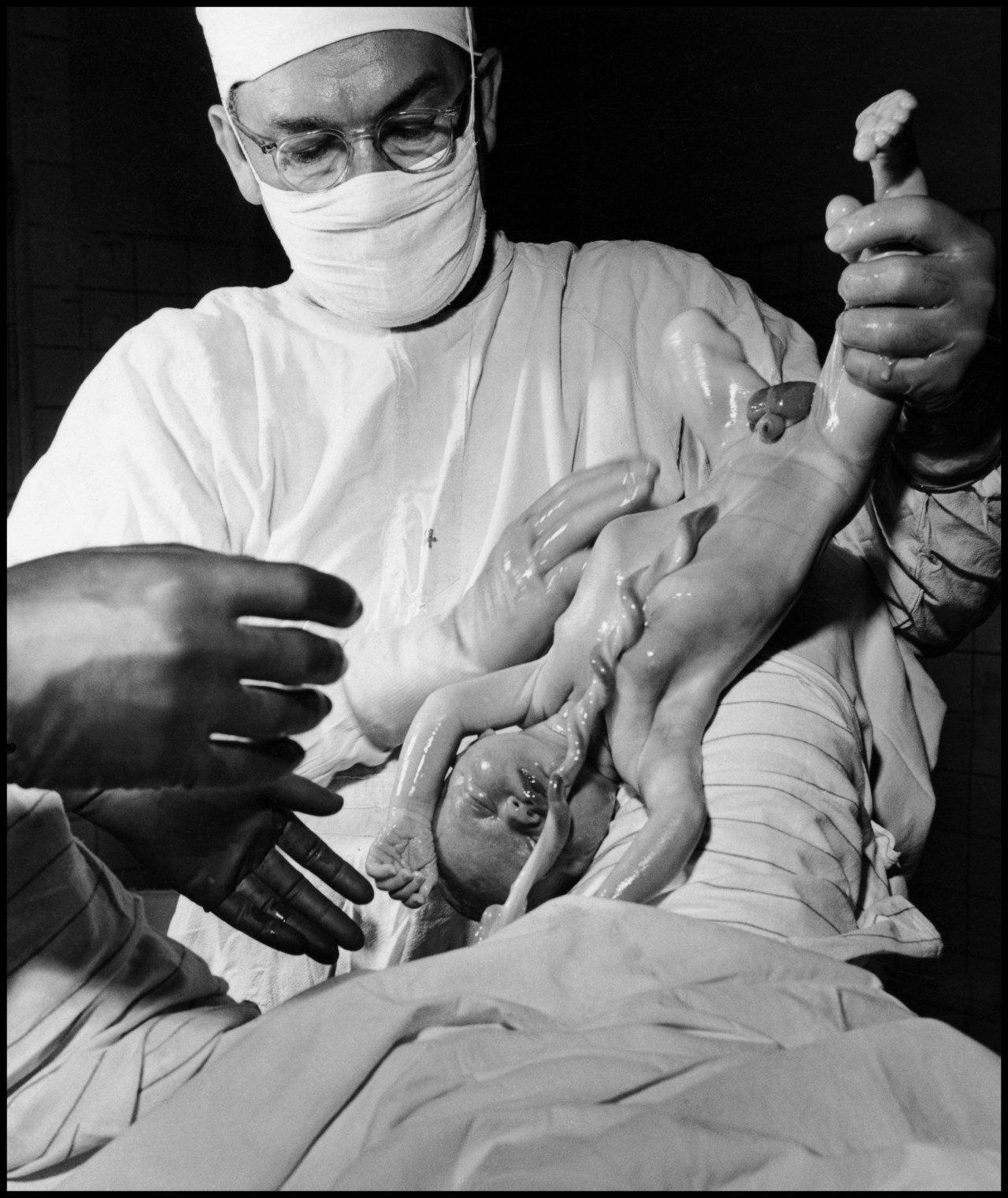

Pardo’s talk dwelt upon the origins of the humanist theme in photography, and Edward Steichen’s seminal 1955 MoMA exhibition The Family of Man, which drew on the work of hundreds of photographers and had attracted more than nine million visitors by the time its global eight-year tour was over. Accordingly the following article features images made by Magnum photographers which were included in The Family of Man exhibition, as well as a number of Wayne Miller’s photos of the show’s opening days at MoMA. Miller himself assisted Steichen in the show’s curation.

When tasked with unpacking and unravelling the complexities, contradictions and misunderstandings wrapped up in the loaded term of humanism, as it relates to the photographic medium, it is wise to kickstart the process by first trying to define humanism and its multiplicity of meanings while also locating the term in its historic specificity. Only then can we turn our attention to how humanism manifests itself in contemporary practice and in particular how it informs or diverges in various practices and ways of looking.

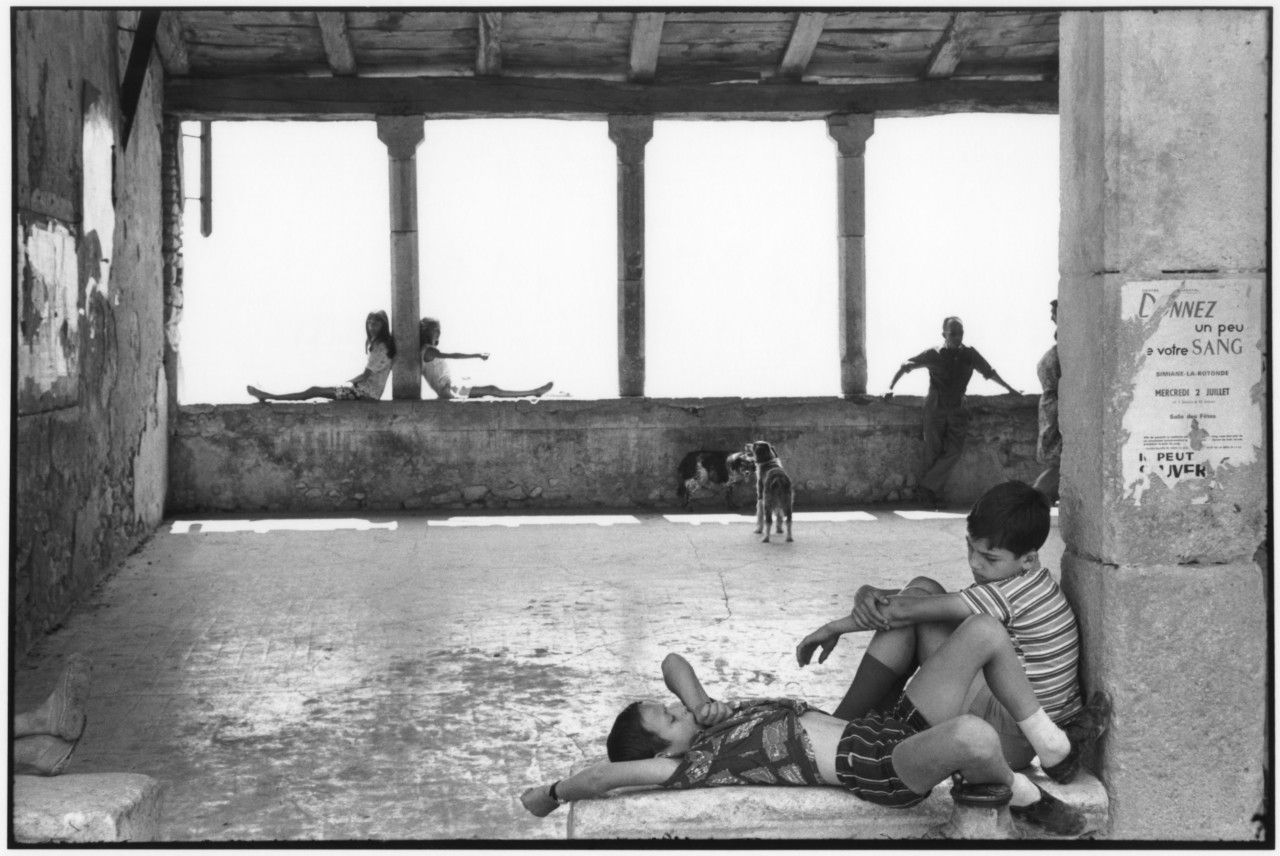

In very broad terms humanism, or humanist photography, was an international movement, whose early arch-exponents were Robert Doisneau, Willy Ronis, as well as one of Magnum’s co-founders Henri Cartier-Bresson whose principal focus was the human being in everyday life.

The movement came to prominence in the interwar and post-War period, particularly in France, where it flourished in the country’s optimistic post-War climate which Cartier-Bresson perfectly expressed in an interview in the 1950s stating that, ‘For a short time the French really believed that they could love another. One felt oneself borne along on a wave of warm-heartedness’. However, it is important to note here that the movement really reached its apotheosis in Edward Steichen’s seminal 1955 exhibition The Family of Man, which we’ll get back to later.

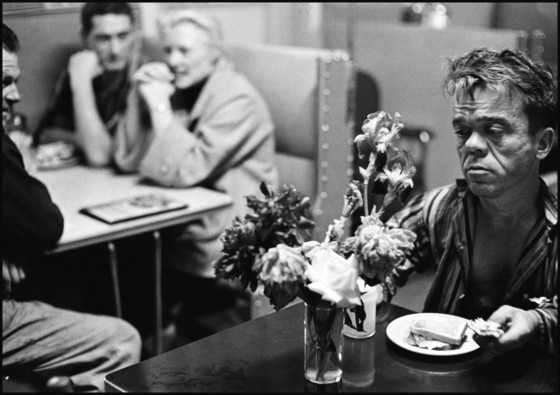

So, we’ve established that French photographers played a pivotal role in the movements’ development, turning their lens not only on everyday life and people but just as importantly on their immediate urban environment, which played a critical role. The streets of Paris, factories, bars, children, lovers and marginal communities were all favoured subjects for seemingly intimate yet realistic portraits illustrating the common man’s way of life, which was celebrated for its simplicity and authenticity. Again, I quote Cartier-Bresson who said his most important subject at the time was ‘mankind; man and his life, so brief, so frail, so threatened.’ And although it is of course important to remember Europe, and to a lesser extent the US, were scarred by the trauma of the two World Wars, I would argue here already that early manifestations of humanism – with its mixture of social realism and poetry – depended on the photographers maintaining a certain critical and subjective distance from their subjects.

"The world view of the humanists placed great emphasis on the unifying perspective of solidarity, the idea that it is through comradeship society can and will change for the better"

-

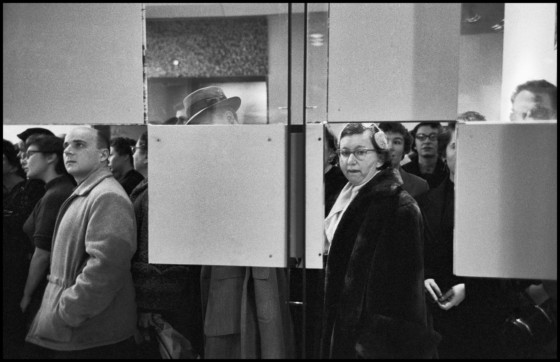

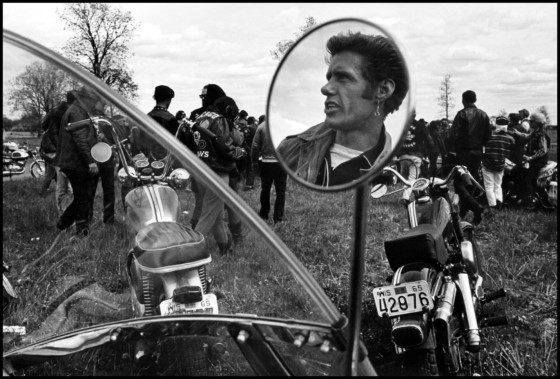

Other key characteristics of early humanism include the centrality of universal human emotions as subject-matter, the framing of the specificity of where and when the picture was taken, a focus on everyday life as it referred predominantly to the working class, a sense of empathy or complicity with their subjects, the viewpoint of the photographer – notably they often positioned themselves as if they were bystanders or participants in the unfolding dramas, which I would contest – and always expressed in black and white photography. The world view of the humanists placed great emphasis on the unifying perspective of solidarity: the idea that it is through comradeship society can and will change for the better.

It is also important to remember that the primary platform for these hopeful – albeit naive and culturally relativistic images – were the pages of the widely read illustrated press, by whom many of these photographers were commissioned. Just as with Instagram today or other social media platforms, the wider public encountered the world through photographs in the press. Indeed at its height LIFE Magazine enjoyed a phenomenal international distribution of over 8 million copies per week.

Ultimately this explosion of interest in photography and its supposedly faithful or truthful representation of the real world was harnessed and to a degree exploited by the flourishing magazine world, by titles such as LIFE and Fortune Magazine which consequently led to the founding, by Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, David ‘Chim’ Seymour, and George Rodger of Magnum Photos, in 1947.

It is no coincidence that the idea of Magnum was dreamt up supposedly in the café of MoMA in New York, which, under the auspice of the celebrated photography curator Edward Steichen, went on to champion this type of photography, and which — as mentioned earlier — staged Steichen’s exhibition The Family of Man. So, from the streets of Paris, humanism found a new outlet and that was through the numerous exhibitions Steichen curated during his tenure at MoMA including Road to Victory and Power in the Pacific, although none would surpass the popularity and influence of The Family of Man.

"The World War II experiences of Magnum’s founders oriented them toward a photography that would contribute to human betterment"

-

The World War II experiences of Magnum’s founders oriented them toward a photography that would contribute to human betterment. And it was this aspiration that was shared by Steichen as he prepared The Family of Man. The show proposed photography as a means through which the tensions and uncertainties of the Cold War era, with the threat of nuclear annihilation ever-present, could be seen in a wider context of human values, emphasising the theme of common humanity against the destructive effects of political polarisation – a phenomenon no less pervasive and damaging today.

The Family of Man reaffirmed a faith in humanity for an audience shaken by the harrowing images in LIFE Magazine of Nagasaki and Hiroshima and troubled by the spectre of global nuclear war. Steichen hoped that the show would illustrate the ‘essential oneness of mankind throughout the world’. Steichen’s focus on common humanity reflected a larger movement, motivated to affirm the basic rights of all peoples as underscored by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, the exhibition was firmly anchored in a Western view of this so-called universal community.

Despite the exhibition’s call for unity and peace, it faced criticism for its cultural relativism and seemed to exacerbate American cultural imperialism with its depiction of the ‘bourgeois nuclear family’. As Roland Barthes comments in his seminal volume Mythologies, The Family of Man offered an essentialist depiction of human experiences such as birth, death and love coupled with the removal of any historical specificity.

By the mid-1960s the humanist project began to fall out of favour as photographers like Bruce Davidson, Danny Lyon and others began to explore a more hyper-subjective position with the world and explored a new social landscape — one that privileged a direct relationship with the subject, that reflected the fractures and dissonance of a more complex and nuanced post-war reality.