Cops, Uniforms, and the Visualisation of Power

Christopher Anderson discusses his new book, COP

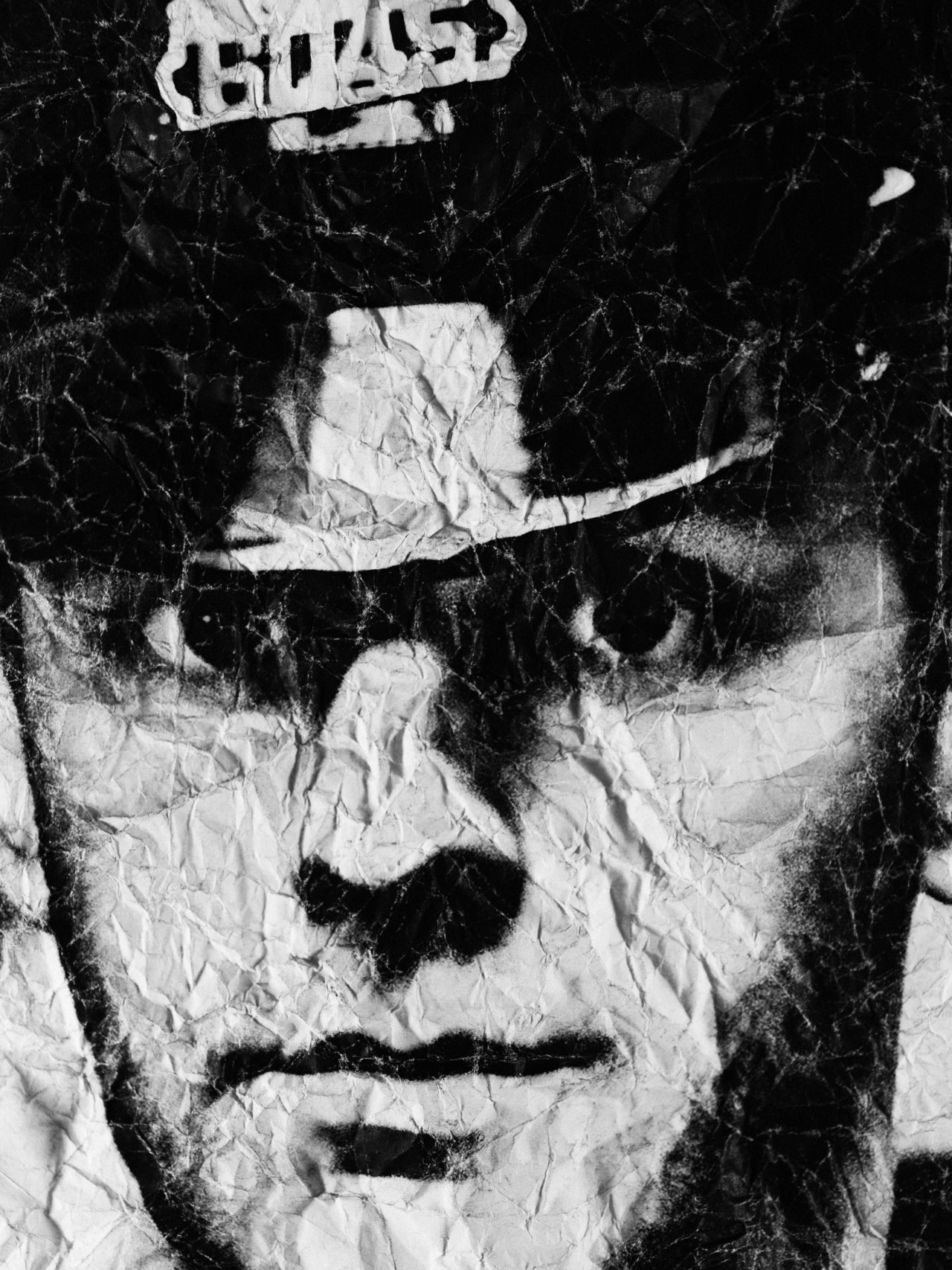

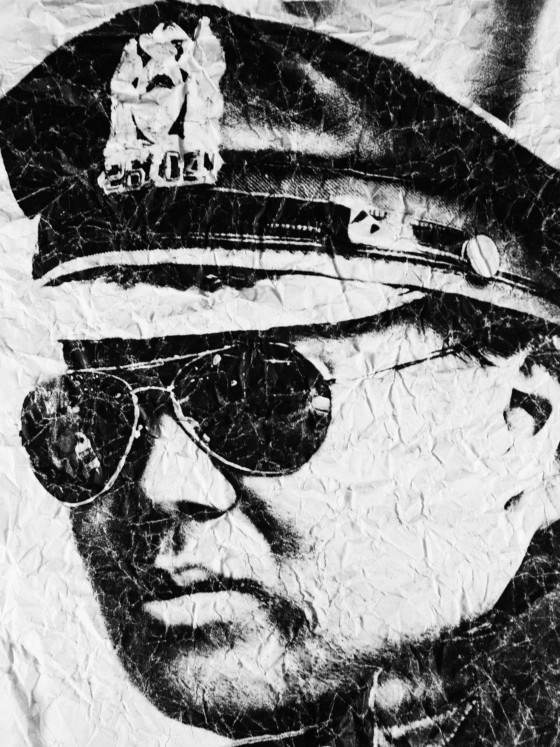

Christopher Anderson‘s new book, COP, published by Stanley/Barker is the result of his photographing police in his hometown of New York since 9/11. In the years that followed the attacks he witnessed the increasing militarisation of the police, and the growth of defensive architecture in the city, and was unsettled by both. Following numerous events including high profile police shootings, and Trump’s election Anderson started photographing the NYPD anew, initially in opposition to the unsettling changes, but over time his feelings about the images changed.

Here, New York-based photographer, educator, and editor of photography publication Matte – Matthew Leifheit – speaks with Anderson about the complexities of the book, the evolution of the images in it, the issues around images of police in contemporary America, and the “changing visual landscape of the nature of authority”.

Anderson will be signing copies of COP at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, on July 17. More information, here.

Last week in Manhattan, I marched in an alternative queer pride march organized by Reclaim Pride Coalition. One of my reasons was that the overwhelming police presence at mainstream “world” pride is troubling to me, given that the event commemorates an uprising against the very same police force. I am not alone in having a strong reaction to the police, most Americans will have some kind of feeling about cops in general, and perhaps even the NYPD specifically.

Given that America has the highest incarceration rate in the world, many of us have experienced the cops first hand and those who haven’t know the force either through television dramas like Law & Order, through news footage depicting its heroism during the 9/11 attacks, or by seeing one of its officers murder Eric Garner in 2014. Others may have acted Officer Krupke in a school play, or dressed up like “sexy cop” for Halloween. The sexual elements evident in the latter are of particular interest to me: in the darkrooms of 1970s gay bars police play was a popular fetish night, where queers acted out the role of their oppressor in sadomasochistic rituals. I myself have never fucked or been fucked by a cop, but I imagine that the thrill in either case is dependent on reducing the person to the symbol of their uniform.

Christopher Anderson’s photographs, collected in COP, approach a similar kind of titillation in reverse, changing bully into body. These pictures use the uniform as a thread to show how the police might not fit into someone’s political agenda, ultimately emphasizing their humanity. Some could read this as outright celebration of our boys in blue. The depiction, though assertively neutral in a narrative sense, is photographically tender — the light is beautiful, the focus is shallow and sensual. Yet, the very act of choosing the police as a subject is somewhat transgressive. There is a half-written rule in the US that you’re not supposed to photograph cops, and these people were also not asked permission.

In my heart, I would like this trespass to go further. Although I firmly believe it’s not art’s job to be moralistic, I can’t help feeling that to humanize the police is not a productive thing to do at this particular moment. And of course this is my view, it is what I bring to the photographs. Christopher Anderson seems open to all of the strong reactions people might bring to his work. Early last week, we spoke about these complicated issues and more.

Do you think of New York as home?

I do, yeah. I lived basically in New York since the late nineties, but about two and a half years ago I moved my family to Spain and now we’re moving to Paris. But yeah, New York will always be home.

Okay. So, I’m interested in this kind of kind of shift in your view of the police. I understand it started as some sort of kind of critical investigation of their increased presence after 9/11?

I wouldn’t call it a critical investigation. I would say that I was just compelled, after 9/11 I was subconsciously and consciously reacting to the world, to my world visually. I was heading off to cover the subsequent wars, but also looking at how America, my hometown of New York, was changing. Sometimes I start making pictures with a sort of vague sense of reacting to something, I can’t quite articulate exactly what that is. I just feel compelled to respond to it visually. I was responding to the changing visual landscape of the nature of authority, the nature of power, security, all these sorts of things, which in New York obviously was changing fast.

Photography was getting scooped up in the overreaction to the events of 9/11, where it was being criminalized. There were a lot of photographers getting harassed for taking pictures, and there was this idea that you can’t photograph anymore, because it was a security threat. So there was a lot of responding to those sorts of things in a very generalized way, in a very vague way. Not, “I’m going to go out and photograph this because I’m investigating something specific.”

I was running off to Afghanistan and Iraq to photograph things, responding to how the world was changing in general. And among those things I was responding to was the sense I had of the changing of this notion of authority, power, and security. And next came Occupy Wall Street, which was all tied up in this sort of post-9/11 world and how it was reacting to ideas of authority and power. And then there was [the issue of] police brutality in America and the era of George Bush and the death of Eric Garner and all these things which were stirring up emotions in me… You feel kind of helpless and you don’t know what to do with that. And as a photographer, I guess you somehow—even as futile as it might seem—you start taking pictures of something just because you’re responding to it.

Anyway, that’s the environment in which these pictures began. Not as a conscious thing of “I’m going to go photograph police now because this is my struggle” – it was just sort of part of what I started noticing in this world. For me, it was not academic, it was more emotional.

"I like the idea that the work, the images present something that is universal and ambiguous and lend different meaning to different people. That's what I find interesting in photographs"

- Christopher Anderson

I think that’s what it should be for artists. But the way that you’ve photographed them for years now is actually very consistent. It seems like the interaction with their face and the uniform is really important to you. And it is a fairly neutral way of photographing them where it seems to just present kind of a portrait without comment. And I wonder, has the work been edited to be this consistent or were you only photographing them in this way throughout those years?

Well, there was a point when I started looking at the pictures and reflecting on what I was seeing because often when I photograph it’s, like I said, a kind of subconscious response, right? And what I started seeing in the pictures, it felt much more sentimental, if I can even say that. And really I didn’t see my protest in the pictures. I saw something else, which kind of had nothing to do with the idea of authority and cops themselves. It was more about that thing the uniform does. The images provide a sort of a cross section, a portrait of working class, immigrant New York.

A book is sort of a proof of thesis for me, and so once you’ve made the photographs and you sit down to make a book, you’re trying to make sense of what it is you want to say. So of course in the edit then I sought to strengthen that thesis. In other words, if you can imagine over all those years of photographing cops here and there for different reasons, I have pictures that make cops look like villains. But that wasn’t what the book became about in the end. So those pictures didn’t have a place in this book. Not because I wanted to show cops as good guys or bad guys, but because the book became about something else.

I always think in photographic work, there’s two things: there’s what the pictures meant as I was taking them, or what I thought I was seeing when I was photographing, then there’s the context of once you put them in a book, what do they mean then? Part of the idea of COP is that the subject is actually a vehicle for something else.

One thing that photographs do really well is perfect ambiguity. It’s one of the particular strengths of the medium, that you don’t have to arrive at a judgement. I’m not interested in art that is moralistic where you come out knowing who is a good guy and who’s a bad guy. Sometimes, maybe most of the time, it’s more complicated and moving to see just a human being.

I’m particularly interested in this body of work because I like the idea that you could go into a crowded public space with a camera and create this almost random sample of really detailed close-ups of people. It seems to prove that anyone is fascinating if you look at them right, which I think is true. But then I also think it’s a really complicated subject. Like you were saying, photographing public space was suspect after 9/11 and one thing you were particularly not supposed to photograph was the police.

Also, here’s a story: One of my students who was a sophomore at college brought in this picture of the New York City Police. In the photograph, it appeared that the cops had sort of cornered this person who was walking with a baby in a stroller at night and they were shining a very bright light at them, pushing them up against this fence in a public park. And I read it as a very scary image. I said, “Oh, this image to me is about what I perceive as the over militarization of the New York City Police force.” And this was closer to the time of Eric Garner, and I stupidly assumed that we all felt the same way about this. Then it turned out that there was a wide array of opinions about that in the room and that some people found even my personal expression of saying that I felt that the police were over militarized was offensive. It may have been upsetting to people who had family in the military or families who experienced 9/11 in different ways, or who knows what else. Cops are a subject that brings up a lot for a lot of different people. I think that’s part of what the book does—it provokes many different reactions and most of them will be vehement. And it seems like you’re open to all of that in the pictures.

Yeah, I mean, all of what you just said, I totally identify with. I think, actually in all my work, even my early book Capitlio about Venezuela and my book Son about my own family, I always think of my work as dealing more with universal themes than what the subject matter seems to be. This obviously isn’t a journalistic documentary about cops or the life of cops. And it certainly isn’t an activist perspective about police brutality and it certainly isn’t a defensive polemic either. It’s none of those things.

I like the idea that the work, the images present something that is universal and ambiguous and lend different meaning to different people. That’s what I find interesting in photographs, exactly that sort of ambiguity, that response that you can have when looking at the picture that is layered and is nonspecific, and there’s just an emotional reaction about something.

In the way that you’ve photographed and edited them, there’s no narrative, they seem more involved with the language of portraiture, in painting or something. Although I could also compare them to a mugshot, or a head shot. A close-up. I guess what I’m saying is you’re showing the thing that is most specific about a human, the face. Yet somehow it manages to not be about that person. And I think this is true of your previous series in Shenzhen also, where the real question is how I might feel about the subject.

Exactly. I view this book as kind of a third in a trilogy, following Stump, (pictures of politicians of the 2012 campaign), and Approximate Joy (the portraits in China). And yes, exactly, also working with this sort of idea of really close portraiture almost to remove context of place and activity. I said this about Approximate Joy as well—there’s this elicit pleasure in getting the opportunity to just stare at another human being so closely. Something feels… voyeuristic is the obvious term. But there’s something about it that feels so like a pleasure to look at another human.

"Because of this naturally occurring control sample of the uniform, I think that helps bring out the differences of the faces. You see women, you see men, you see race"

- Christopher Anderson

I think it’s exciting.

And not even in a sexual way, even though I think there is some sensuality in some of these images. I don’t mean that necessarily in a sexual way but just the idea of looking, intensely looking at someone.

Do you know Robert Bergman’s work? This is maybe an out of nowhere reference, but he is someone whose life’s work is basically looking at people’s faces very closely in photographs. And honestly I think, what could be more exciting than that? You’re specifically doing it in a way where the subject hasn’t been engaged in the portrait. I don’t know about voyeurism, but there is some element of being this sort of non emotionally dead surveillance. It’s like a surveillance that feels.

I also think about what clothes actually say about anyone, or what a uniform could actually mean to put on, in terms of its relationship to who you are as a person or your identity.

Oh absolutely because the uniform works on a couple of levels. First of all, it’s right there injecting this question of authority and security, but then it also becomes the control sample. You know what I mean? When you talk about scientific testing the control sample is the thread by which you’re able to actually distinguish difference. Because of this naturally occurring control sample of the uniform, I think that helps bring out the differences of the faces. You see women, you see men, you see race, you see all of these things that are the beautiful differences of humanity, and somehow putting them all into similar clothing makes you more aware of that.

Yes I think often these people are reduced to sort of symbols of political stances for me, and the uniform tends to enhance that reaction when I encounter it in the world. Your photographs use it to do the opposite thing. After all we’ve been saying about ambiguity in photography and the role of art, I can’t shake the feeling that this work refuses to acknowledge some of the problems that exist here. What do you hope to accomplish by humanizing the police?

I don’t hope to accomplish anything. I didn’t formulate a hypothesis and then go make photographs in support of that hypothesis. As I described in detail earlier, I made these pictures while reacting to something…as a response. Much later, looking at the images, I saw something in the photographs that I don’t think I was aware of while I was making them. If they are humanized in the pictures…and I agree that they are indeed humanized…it was not my intention. It was not something I set out to accomplish. It is not something I “hoped” for. It was the totally unexpected result of really looking at something closely. I find that fascinating, personally, and that is part of what I am drawn to in looking at the work. But humanizing the police is not the agenda. More to the point, I don’t think this book has anything to do with police. The uniform is just a frame to highlight something totally different. Maybe I could do the same book with construction workers or nurses, for example.

Alex Majoli was looking through the book a couple of days ago and his first reaction was the fact that the uniform sort of disappears after three pages. You don’t even think about the profession anymore. That is a visual experience that is interesting. But it isn’t a political agenda.