A World in Color: France, Monuments and Memory

Discover unseen archived images of France, home of Magnum's first headquarters and the origins of photography itself

After traveling to Czechia, Italy, and Belgium, A World in Color unlocks Magnum’s unseen archives of France, the birthplace of the cooperative and photography itself. A project in partnership with Fujifilm and the Heritage and Photography Library of Paris (MPP) to digitize the Paris color archives, A World In Color’s latest chapter revisits France’s monuments and structures, from the emblematic to the unexpected. Beginning with Burt Glinn and Inge Morath in 1958, these photographs retrace the steps of Magnum photographers who documented the country’s changing social fabric.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, advances in photography rapidly unfolded in France. The first photograph was created by Nicéphore Niépce in his home in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, using a process called heliography. At the turn of the 19th century, the Lumière brothers found a breakthrough in color photography.

Paris is also Magnum’s first home. As France dug itself out of the rubble of the Second World War, the agency began to take shape. Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson and George Rodger — three of the agency’s founders — all documented the liberation of Paris in 1944, having beaten improbably odds to get there. Capa, who survived the D-Day landings while on assignment, wrote in his memoir Slightly Out of Focus of his arrival in the capital on American tanks: “I was returning to Paris — the beautiful city where I first learned to eat, drink, and love.” Then, he spotted a familiar monument: “We drove through the quartier where I had lived for six years, passed my house by the Lion of Belfort. My concierge was waving a handkerchief, and I was yelling to her from the rolling tank, ‘C’est moi, c’est moi!’”

We naturally gravitate towards monuments. They remind us of a particular history — sometimes our own — within an immeasurable narrative. The word monument is from the Latin meaning “something that reminds.” Photography does the same; it reminds us and therefore situates us, preserving a fragment of a memory while writing us into the present. The framing of monuments and structures in this selection often surprises us, providing a vivid backdrop throughout both the country’s transformative moments — its post-war years and revolts — as well as the fleeting instances of everyday life.

Burt Glinn, who Susan Meiselas called “one of the most generous members of Magnum,” frequented Paris after he joined the agency in 1951. Glinn took an early leap into color in the 1950s, and although the majority of his lifework is in black and white, color remained a consistent language throughout his career. In 1954, over a drink at the Chelsea Hotel in New York, David “Chim” Seymour tried to convince Glinn to move to Paris from Seattle, where he worked for LIFE. “Boychik,” Chim said, “[…] You have to define yourself — instead of being a local photographer, you could be global.” The following year, Glinn left LIFE and visited Paris, where he embraced a newfound creative freedom. Chim helped him secure a story on American striptease at the Crazy Horse Saloon, and Robert Capa instilled in him a sense of spontaneity, a driving force behind some of Glinn’s self-funded projects.

In 1958, Glinn captured a quintessential Parisian monument: the 19th-century Sacre Coeur church, dominating the hill of Montmartre. Glinn allows simplicity to take hold: the eggshell white domes gleam against a cloudless, blue sky. On the terrace overlooking the city, a couple embrace next to a lone, troubled woman and a quizzical pair, encapsulating the way urban strangers routinely walk in and out of each other’s lives.

Glinn also photographed a relic from Montmartre’s artistic heyday: the “P’tits Poulbots” of the République de Montmartre. A philanthropic association founded in 1921 by Francisque Poulbot and other artists, the République de Montmartre helped local children living in poverty. Glinn shows a young troop dressed as the working class sans culottes of the French Revolution, a tradition still practiced in the association today. Afterwards, Glinn captured the children indulging in a glass of red wine (serving alcohol to children under 14 was only banned in France two years earlier).

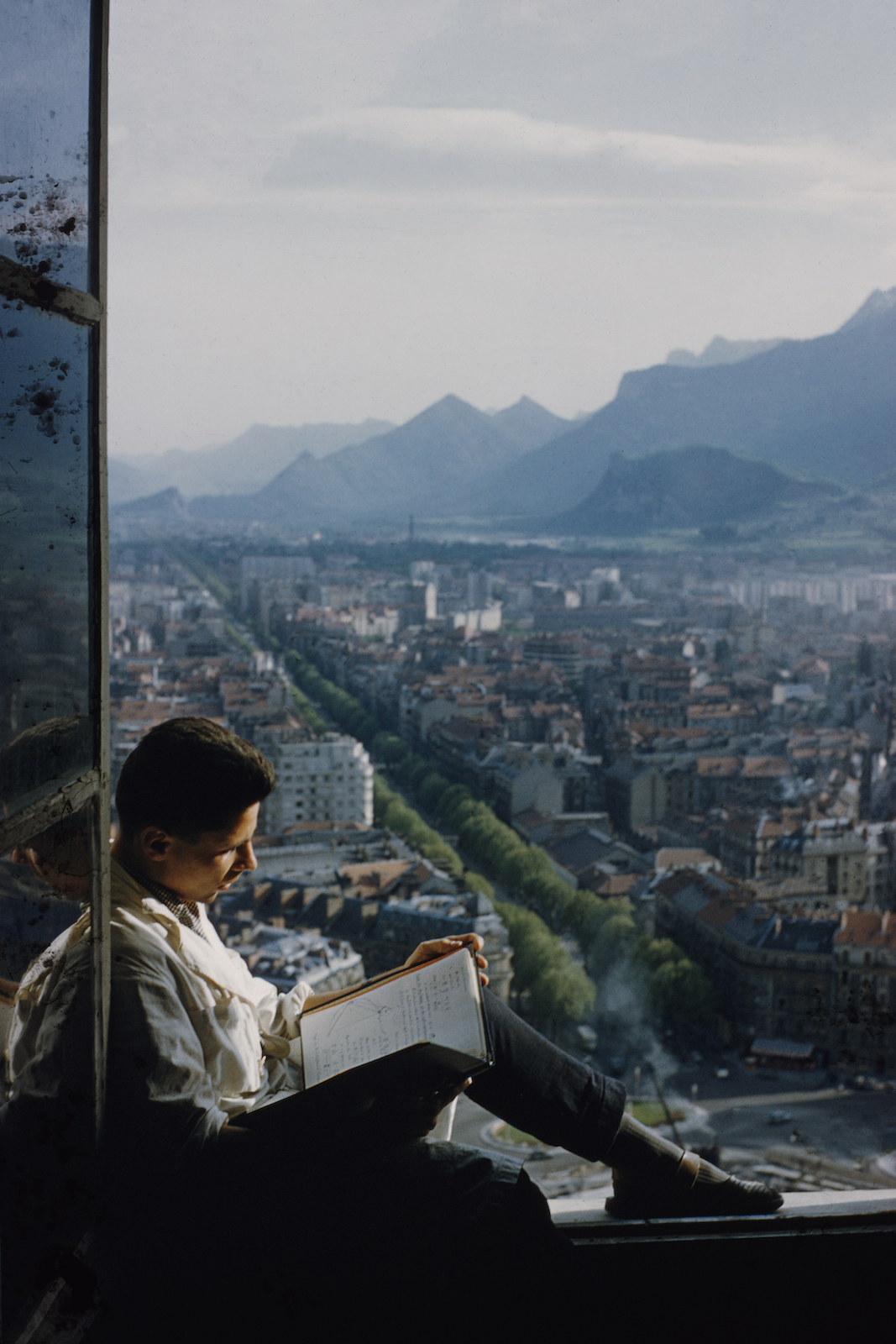

That same year, Austrian-born Inge Morath — the second woman to join Magnum after Eve Arnold — captured a student reviewing their notes in the former Institute of Geology at the University of Grenoble. An inviting poetry punctuates Morath’s color photographs, creating a distinct intimacy with the places we inhabit. Now an aparthotel, the building shares a steep slope with the famous Bastille, perched high above the city.

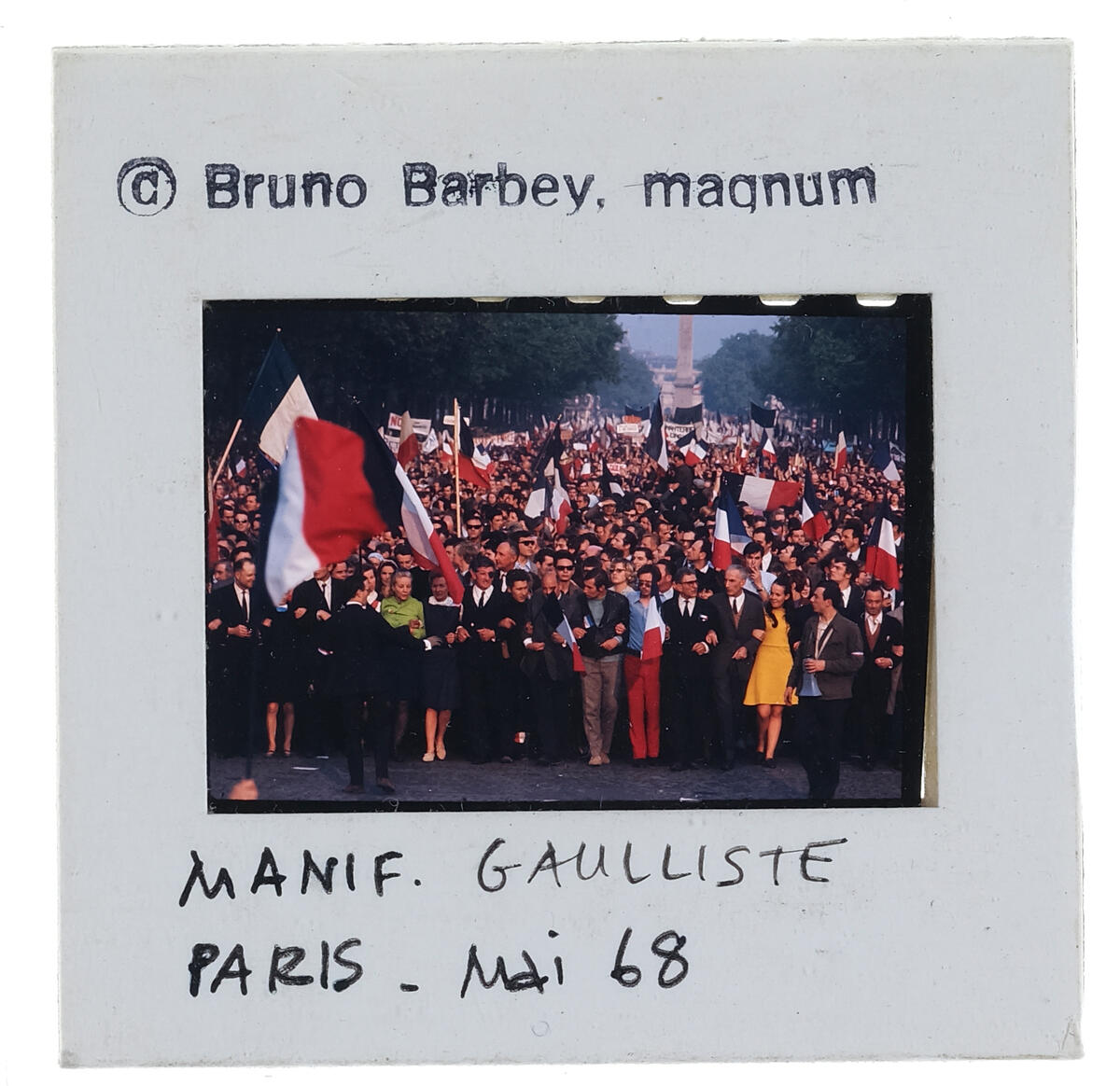

Over the next decade, the country’s underlying post-war strains began to surface. In May 1968, Paris erupted in a revolt, a pivotal moment in modern French history. Bruno Barbey’s documentation of May ‘68, predominantly in black and white, became synonymous with the tumultuous student-led demonstrations. Ignited by the disillusionment in President Charles de Gaulle and a paternalistic society, French protestors were largely inspired by the anti-Vietnam war protests in the United States. They denounced inequalities that stifled the working class and traditional social codes that repressed the politically engaged youth. One of the few color photographs from the series, this unseen image shows the opposition — the Gaullist march that quelled the uprising in its final days.

“Naturally, the French people supported the students at first because they didn’t like the way the police were beating the crowd,” Barbey recalled. “But eventually, after weeks and weeks of protests, people were fed up with the strikes, they wanted to fill their petrol tanks.” On May 30, approximately half a million people flocked to the Champs-Élysées, bearing French flags and chanting the Marseillaise in support of de Gaulle. His party won the subsequent National Assembly elections, and the dust slowly cleared.

At first glance, the famous boulevard and the Obélisque de Louxor at Place de la Concorde in the background seem to symbolize a nationalist restoration of order. However, a seismic shift had taken place: the protestors had forced open the door to an era of intellectual and cultural liberation. De Gaulle would resign just a year later.

In 1979, Dennis Stock traveled to rural Provence, taking vibrant color portraits of nature in the footsteps of the Impressionists. For Stock, painters were “the masters of color.” In Arles, the setting of A World In Color’s next FUJIKINA in July, he captured two girls in traditional Provençal dress striding across the walls of the Arènes, a Roman amphitheater built in 90 AD.

A few years later, further south in Nice, Stock photographed the luxurious Hotel Negresco, a beach-front séjour that once hosted Dali, Princess Grace of Monaco, the Beatles, Louis Armstrong, and Elton John. An art gallery in its own right, it houses works by Niki de Saint Phalle, Renoir, and Hyacinthe Rigaud’s portrait of Louis XIV. Juxtaposing the palatial hotel and the palm tree, Stock politicizes the scene: “Modern architecture in some ways is trying to supplant the majesty of tall trees and reeds; they’re trying to have us revere possibly what shouldn’t be revered,” Stock said. “That’s usually one of the signs of decadence.”

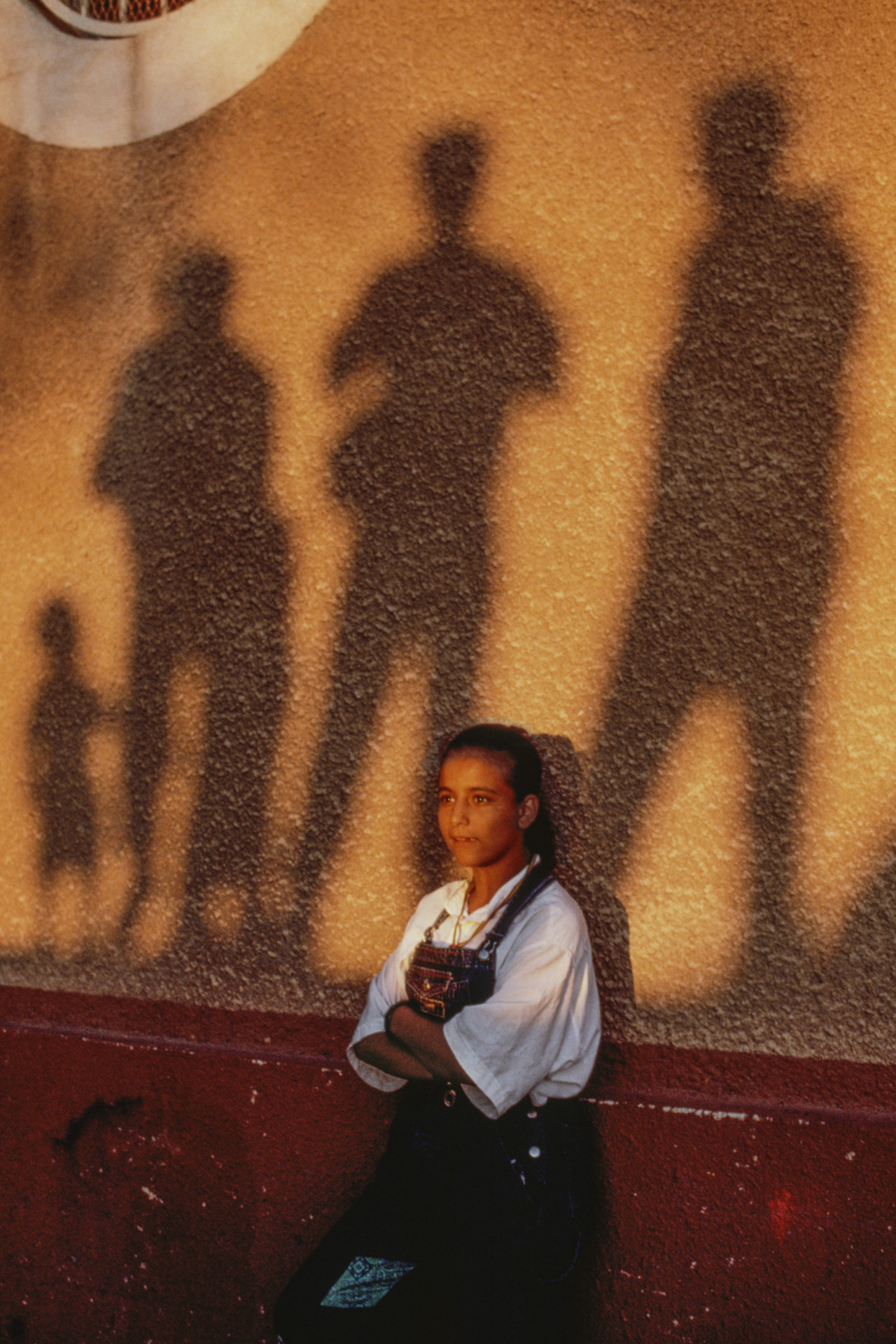

Steve McCurry was drawn to a less mythologized structure: the Bellevue housing project in Marseille. Completed in 1961, the immense apartment blocks were part of an urban project to construct “better, cheaper, and faster.” In the 1960s, it was mostly populated by Algerian, Tunisian, and Moroccan émigrés. However, the appalling living conditions were largely neglected by local authorities. Around the time McCurry took this photograph, up to 5,000 people were living in a total of 800 apartments. In 2020, 55% of the residents, many from the Comoros, still lived below the poverty line. McCurry documented the Bellevue residents and relayed their stories, calling attention to systemic racial disparities within the country.

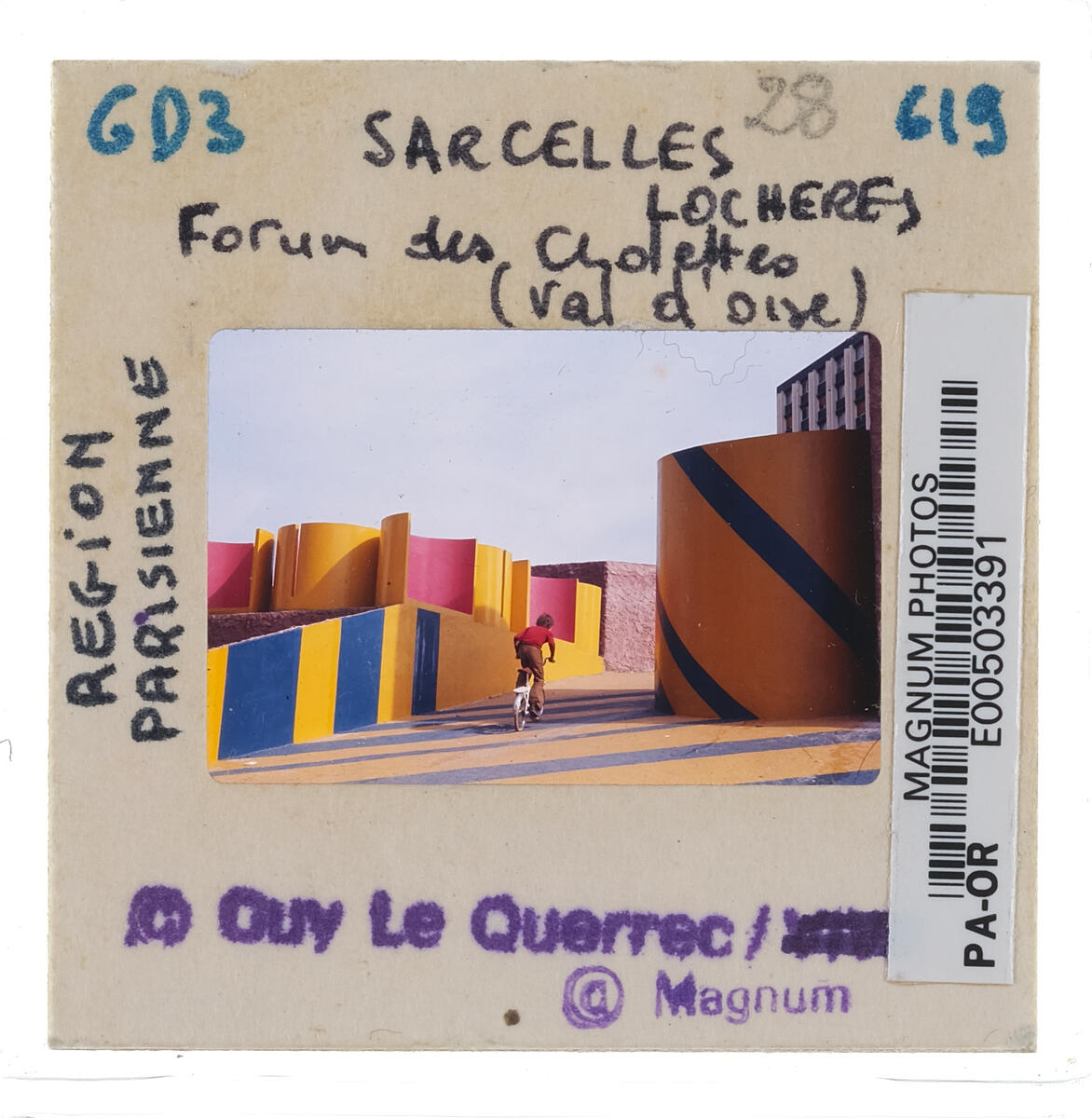

Guy Le Querrec also photographed a series of concrete housing projects and Brutalist buildings in the Parisian suburbs, or “dormitory towns.” Known for his portraits of jazz musicians and his love for the genre, Le Querrec’s image preserves the avant-garde, improvisational styles of the era. When Le Forum des Cholettes, a cultural center in the northern suburb of Sarcelles, shuttered in 1998, the confectionary colors that Le Querrec captured had long faded. It was finally demolished in 2018.

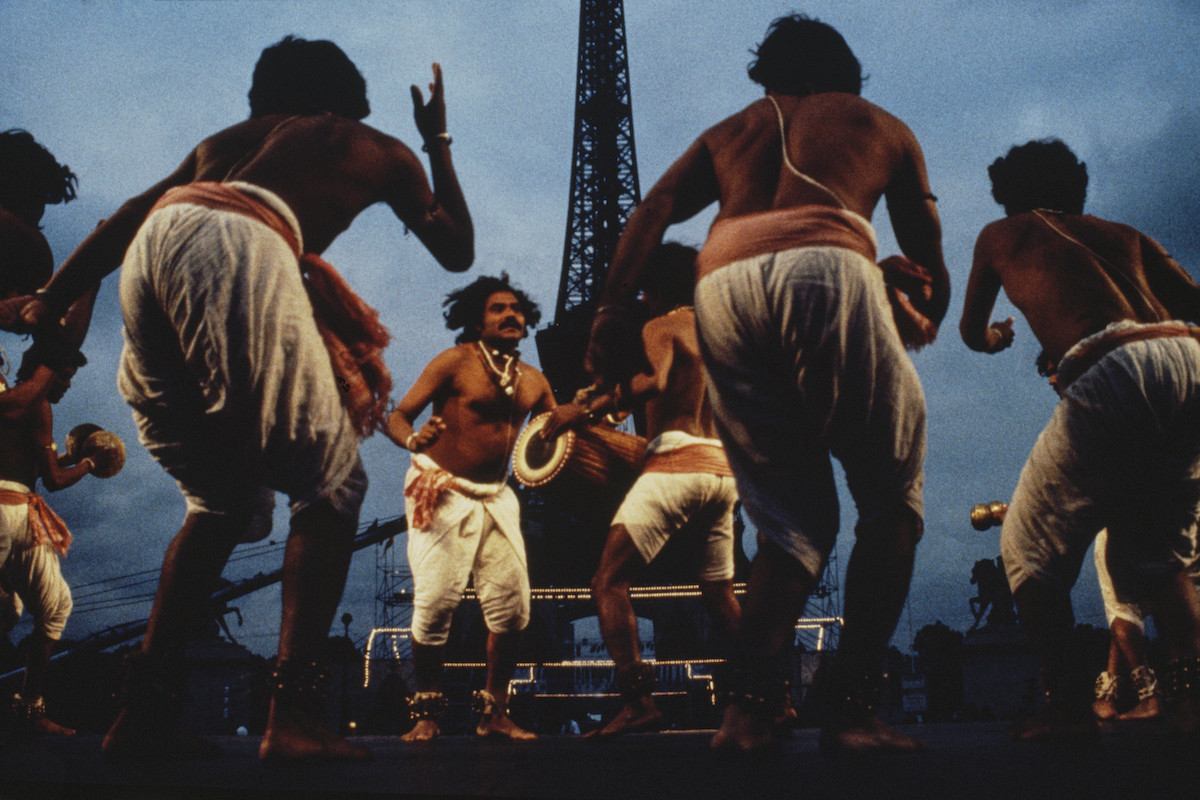

“You must take endless precautions, in Paris, not to see the Eiffel Tower; whatever the season, […] the Tower is there,” wrote French writer and thinker Roland Barthes. The Eiffel Tower is the “gateway” into the “essence” of the capital, Barthes notes — it is a right of passage, an undeniable symbol.

Almost exactly 100 years after the Tower was completed for the World’s Fair in 1889, where people from the French colonies were put on display, Raghu Rai captured dancers reclaiming the space on their own terms. In 1985, he photographed the opening ceremony of the “Year of India,” a series of performances held across the country to celebrate Indian culture. Framing the dancers to appear larger than life under the Eiffel Tower’s silhouette, Rai’s distillation of dynamism and movement is characteristic of his work.

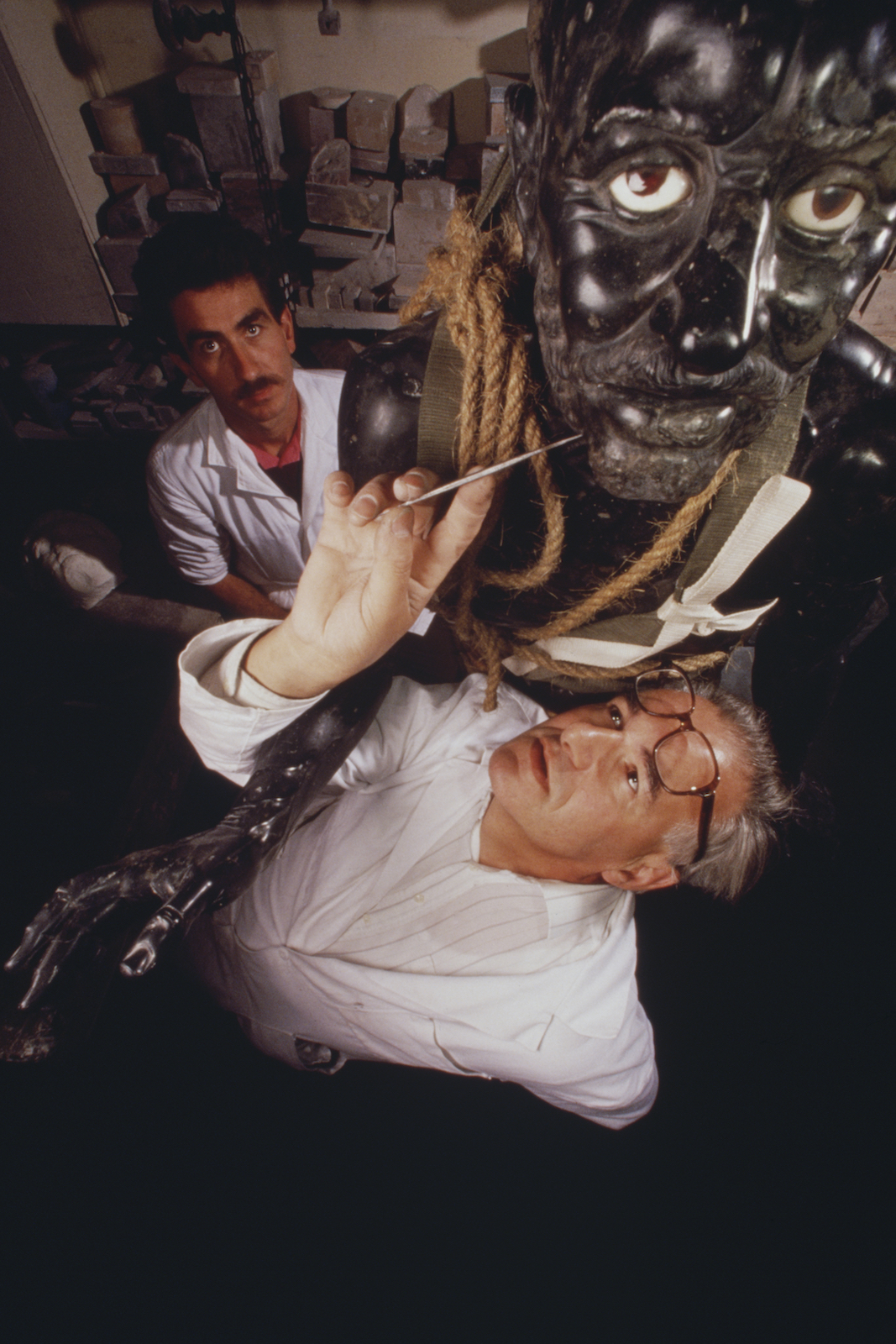

Elsewhere in the archives, restorers in the Louvre inspect the 2nd-century AD “Dying Seneca”; a passenger in a vintage Paris metro reads the classic Que sais-je, a Montaigne-inspired general knowledge series; ruins lie desolate from the Battle of Verdun during World War I; and friends rollick on the French Riviera.

Commanding light and shadow in Arles, Leonard Freed also photographed renowned Spanish actress, flamenco dancer and singer Lola Flores in mid-movement in 1988, seven years before her death. Freed captures her eye perfectly illuminated between the shadows of the pergola.

Revisiting the French archives reveals what compelled Magnum photographers to keep pursuing the unknown in the earlier decades of the agency. “One of the great temptations,” Burt Glinn said, “is when […] you’re going down a road, and you think maybe there will be some action down there. And the easiest thing in the world is to convince yourself that the odds are not so good. And that was the other thing that Bob [Capa] taught me. He said, ‘when you start down a road, go all the way down, sometimes you’ll find nothing and sometimes you’ll find everything there.’”

Live Events

Discover these images and more at the next live FUJIKINA event in Arles at the Les Rencontres de la photographie festival. The exhibition will reveal additional unseen images from the France color archives curated by Magnum photographer Gregory Halpern, alongside original slide sheets. Halpern also presents an exclusive new series of photographs commissioned for the event using the FUJIFILM GFX100 II, taken at the birthplace of photography itself: the home of Nicéphore Niépce. On July 9, Halpern will be presenting his series live at the FUJIKINA event, and on July 10, Raymond Depardon will be in conversation with Matthieu Rivallin, Head of the Photography Department at the Médiathèque du Patrimoine et de la Photographie.

FUJIKINA ARLES

GALERIE ARENA

16 Rue des Arènes, 13200 Arles

July 8-August 31, 2025

With Gregory Halpern and Raymond Depardon

Shop three exclusive prints from the French unseen color archive in the Magnum Store.

Follow the full series via our World in Color newsletter. Subscribe here.