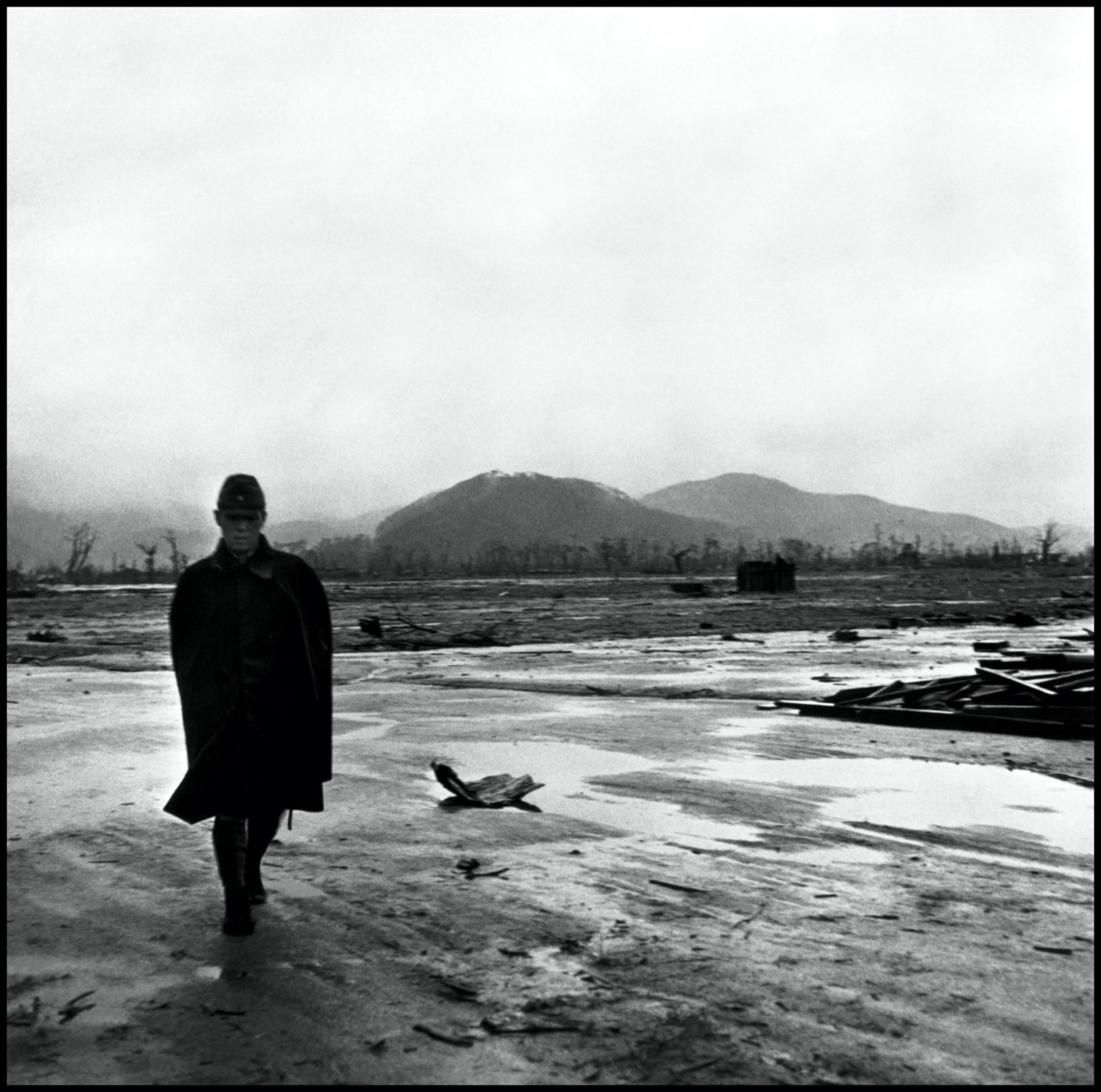

Japan 1945: Hiroshima Aftermath

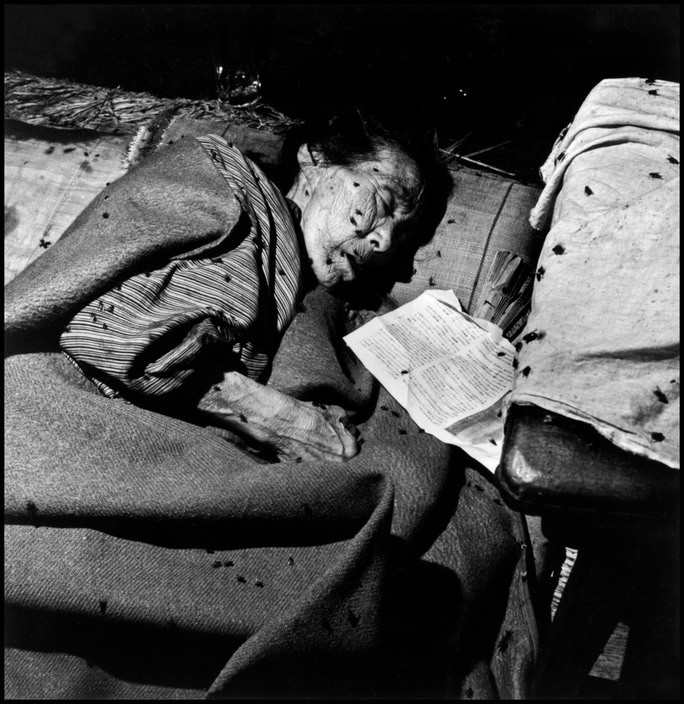

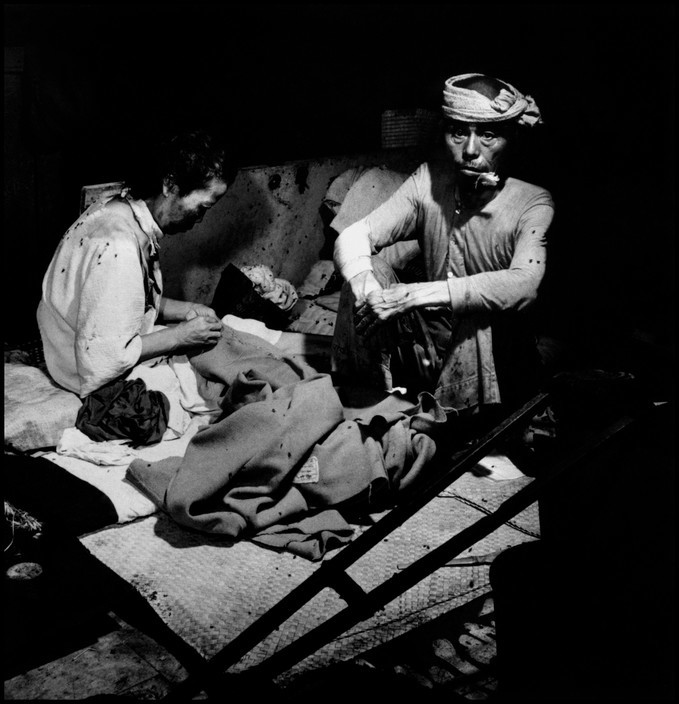

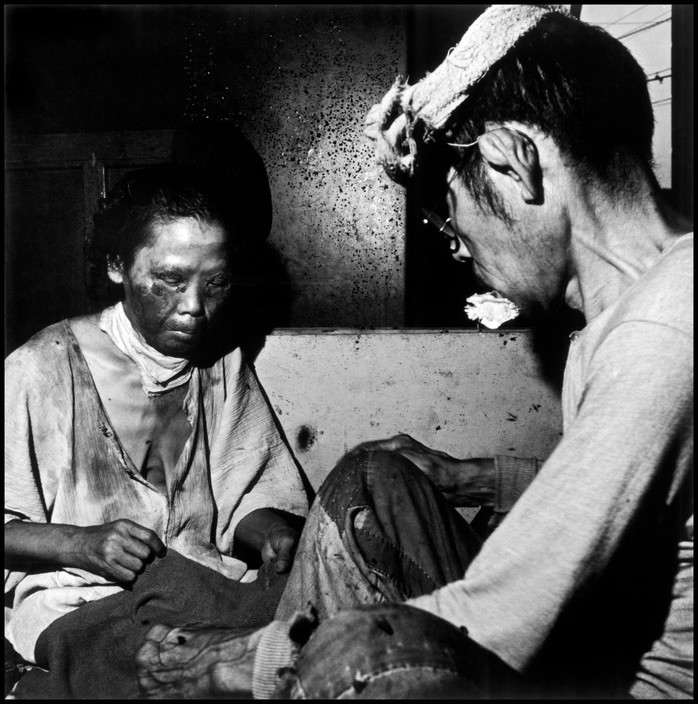

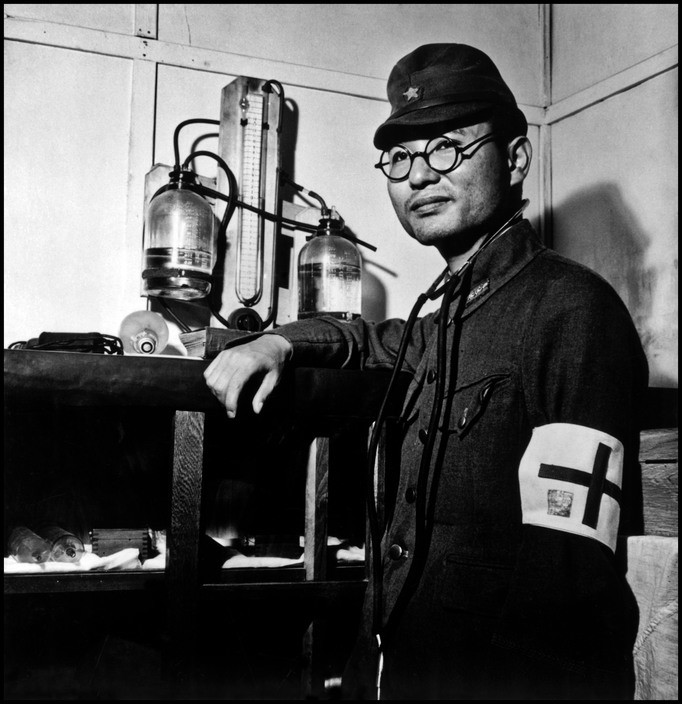

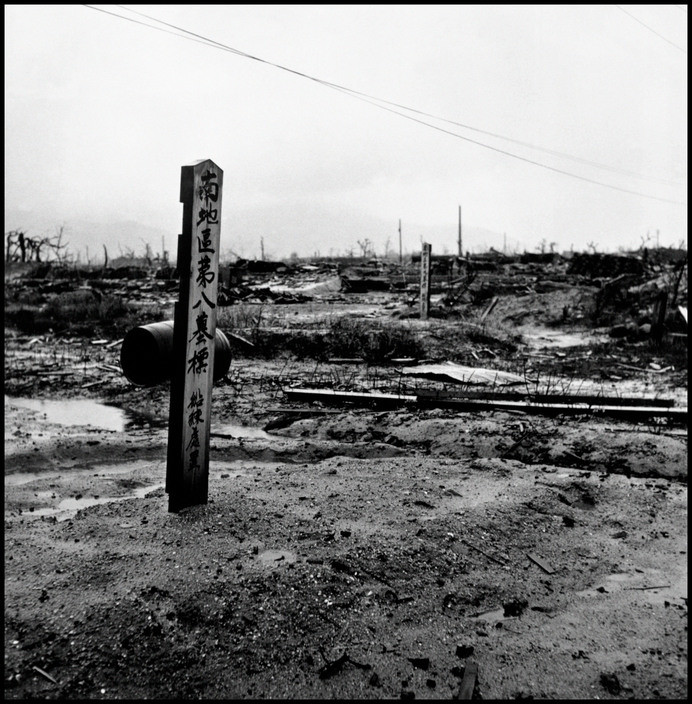

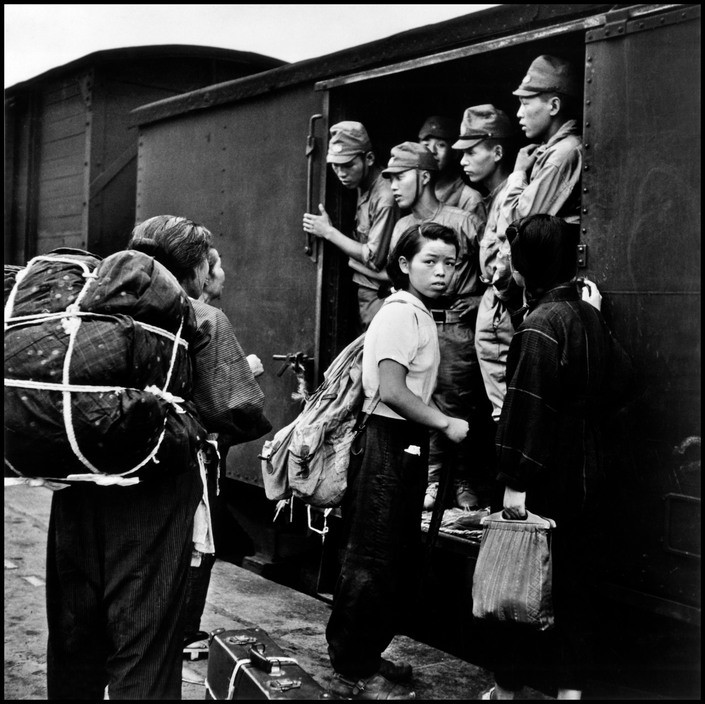

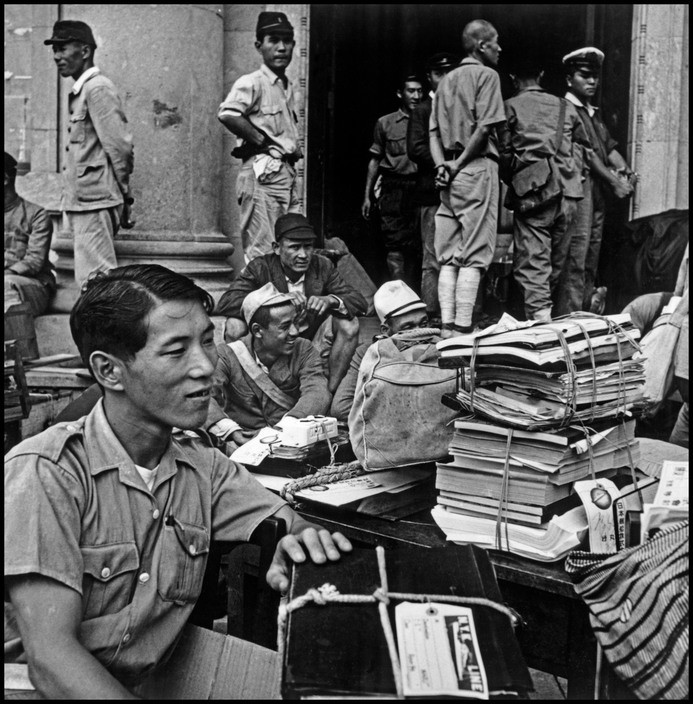

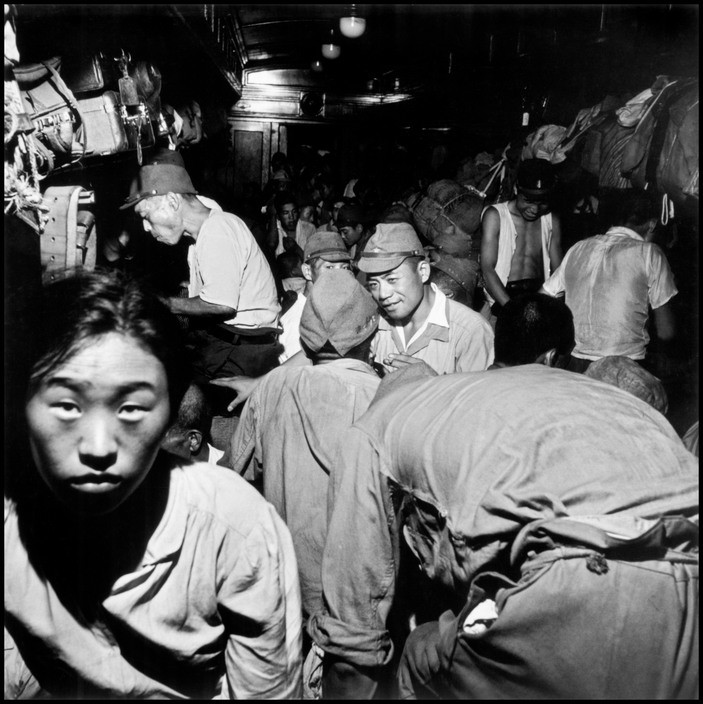

One month after the American atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, 80 years ago this week, Wayne Miller photographed the devastation of the city and its people

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. bomber Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb named “Little Boy” on Hiroshima, a Japanese city with a population of about 300,000. The force of the atomic blast was greater than 20,000 tons of TNT. According to U.S. statistics, 60,000–70,000 people were killed by the bomb. Other statistics show that 10,000 others were never found, and more than 70,000 were injured. Nearly two-thirds of the city was destroyed.

Three days later, on August 9, the day after the U.S.S.R. declared war on Japan, another atomic bomb called “Fat Man” was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, which had a population of 250,000. About 40,000 people were killed by the Nagasaki bomb, and about the same number injured. On August 14, Japan agreed to the Allied terms of surrender.

Wayne Miller was among the first photographers to enter the city of Hiroshima, where he documented the devastation inflicted by the atomic bomb. He regarded the horror of war as a product of ignorance and was determined to use photography as a means to help dispel this. “We didn’t know the people we were fighting. They didn’t know us. Maybe if we knew each other better, the War would be a different kind of war,” he explains in The World is Young, a short documentary in which Miller reflects on his life and work.

80 years later, in 2025, an exhibition by Antoine d’Agata at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo documents the faces of the organization Nihon Hidankyo. Winner of the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize, Nihon Hidankyo is a grassroots organization composed of hibakusha, or atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Titled A Message to Humanity, the exhibition presents archival work around the devastating aftermath of the atomic bombs, and new work around those who survived — encapsulating a message of peace for future generations.

“One day, the hibakusha will no longer be among us as witnesses to history,” the Norwegian Nobel Committee wrote in their statement. “But with a strong culture of remembrance and continued commitment, new generations in Japan are carrying forward the experience and the message of the witnesses. They are inspiring and educating people around the world. In this way they are helping to maintain the nuclear taboo — a precondition of a peaceful future for humanity.”

A Message to Humanity is now touring the world on the Nobel Peace Boat, calling at Vietnam, Singapore, Mauritius and South Africa, before heading to Europe, the United States, and Latin America.