“Short Hair Shorthand”: The Far Right in the UK Through the Magnum Archive

Three Magnum photographers reflect on their experiences photographing extreme anti-immigrant sentiment in the British Isles, and the dangers of focusing on aesthetics when documenting the right-wing

This is the first of a two part series looking at far right movements and their supporters through the Magnum archive. The second will focus on the far right in the United States.

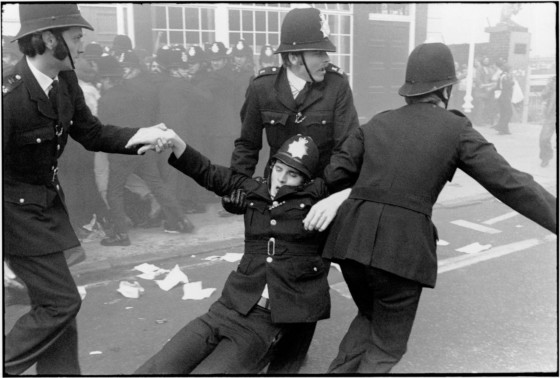

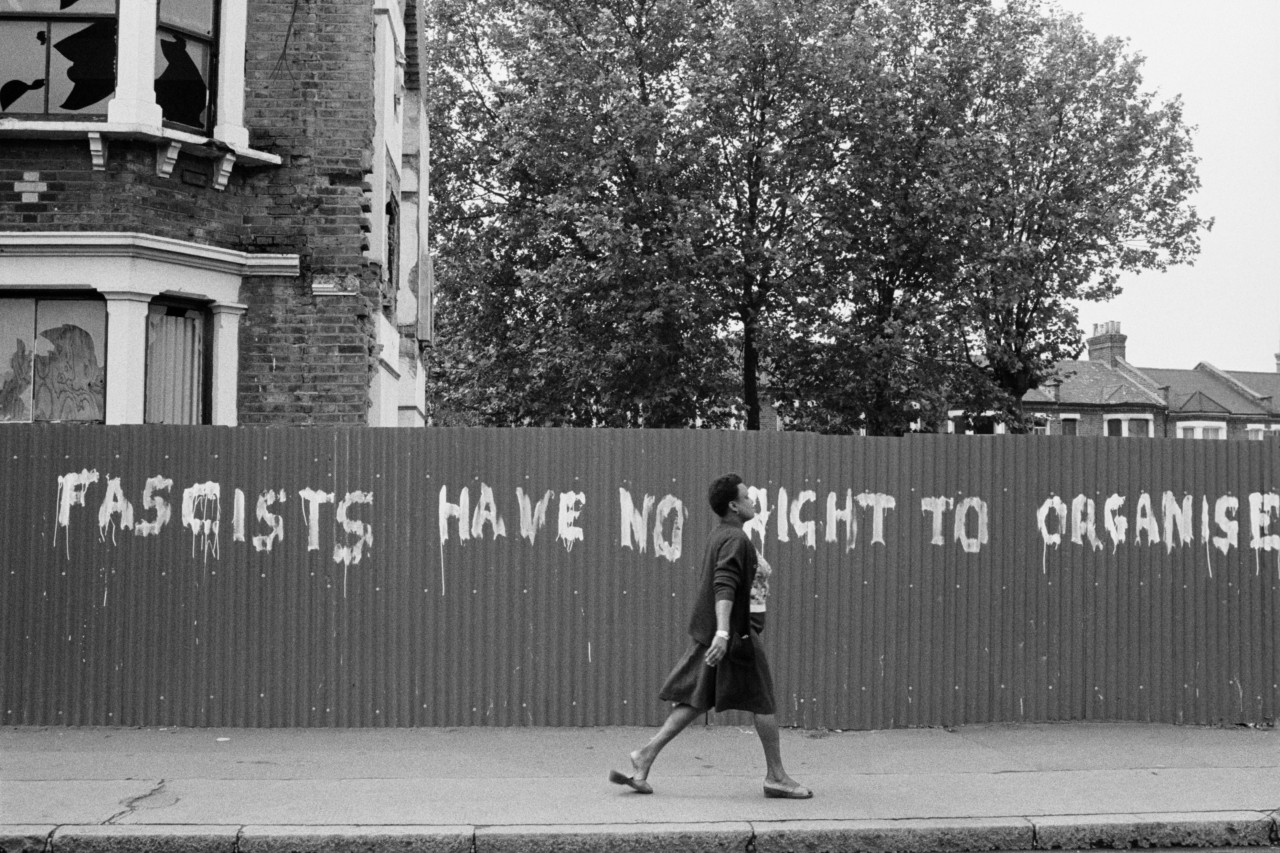

Lewisham, London, 13 August 1977. 500 members of the far right National Front plan to march across the borough and into its town centre; about 4,000 counter-demonstrators have come out to stop them. About 5,000 police are in attendance but by late afternoon pitched battles have broken out on the streets. 56 police officers are injured and 214 people are arrested; police riot shields are used for the first time on the UK mainland. Here, pictures by Chris Steele-Perkins and Peter Marlow show that heavy-handed policing of counter-protestors was as much a part of the story as the activities of the far right minority on the day.

It’s an event that came to be dubbed The Battle of Lewisham, and seen by many as a high-water mark for far right activity on British streets. But, says Steele-Perkins, it didn’t seem like it at the time. There on the day, “running around, trying not to get hit”, he thought it could be part of an ongoing spiral into chaos.

“It was out of control!” he says. “It was a kind of peak in London, of that kind of fighting in the street between the police and the demonstrators, but there wasn’t any sense that that was the case at the time. I thought it would go on for years.

“Part of the idea I had at the time was that civil disturbances could escalate into the situation we had in Northern Ireland,” he adds. “The streets in west Belfast were battle zones with soldiers with live ammunition on the corners, and I thought this could happen in mainland Britain.”

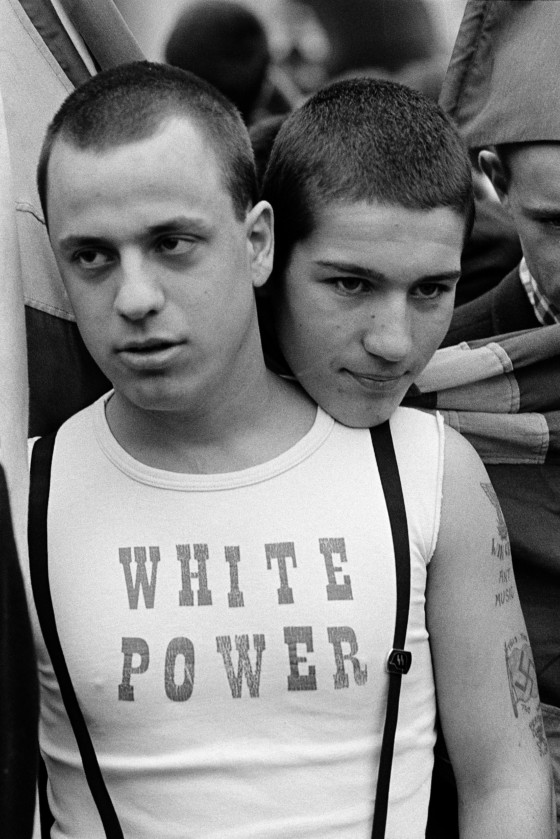

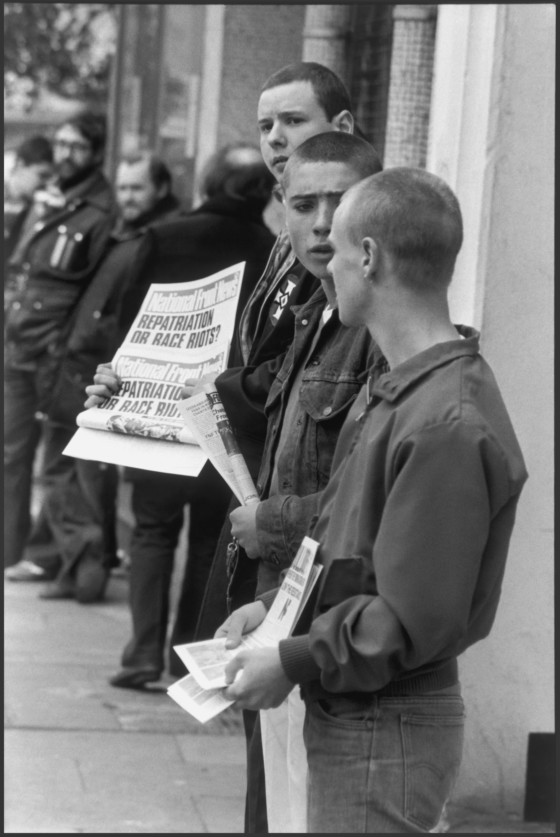

Steele-Perkins kept on photographing far right supporters throughout the 1980s, capturing images that still look disturbing today. Those who turned out onto the streets to support views such as ending immigration and repatriating all settled immigrants to their ancestral homelands sported shaved heads and White Power t-shirts, and were happy to be photographed giving Nazi salutes.

The images are accurate, he explains, but they only tell part of the story and he thinks they’re less effective because of it. “The far right is depicted in photographs as the burly boys because it’s easy to do it that way,” he says. “Skinheads shouting perhaps looks more intimidating than people with long hair shouting.”

In taking these photographs, Steele-Perkins was following a long tradition for Magnum Photos, whose members have documented those on both the right and left of the political divide since – well, since the very start. The work Magnum co-founder Robert Capa brought with him from the Spanish Civil War and from World War II showed exponents of radically disparate views, from the International Brigades in Madrid in 1936–1938, to a French Nazi-sympathizer who had her head publicly shorn upon the Liberation of Paris in 1945.

Other photographers at Magnum have continued to carry this baton, with Eve Arnold capturing members of the American Nazi party listening to Malcolm X in 1962, and Bruno Barbey showing a far-right demonstration in Paris during the more famously leftist protests of 1968. But today Steele-Perkins is critical of the images he took of Britain’s far-right, describing them as “short hair shorthand”.

The racist skinhead subculture depicted in Steele-Perkins and Berry’s images grew out of an earlier, broader skinhead culture originating in the late 1960s amongst young working class people in London, predominantly living in multicultural areas, who were influenced by mod and Jamaican rude boy fashion. In the ‘80s, political affiliations amongst skinheads diverged, with a far right fringe attracting extremist and racist individuals — it was this group which in much of the public’s view came to be most associated with the wider skinhead aesthetic.

Steele-Perkins recognizes the dangers of focusing on aesthetic tropes.“The real problem is the people who don’t talk – the political classes behind it are really to blame. The others are just foot soldiers, some of whom are not too bright and just want to get into a rumble. […] This is where photography and representation have a problem,” he adds. “The message is maybe not carried in the picture in same way [if it doesn’t show a skinhead].”

Ian Berry photographed National Front marches in the UK in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, and has captured his fair share of shaved heads and racist insignia. But, he says, the people who adopt this look are not the only people on the marches. In fact his impression is that far-right demonstrations these days include attendees who appear more middle-of-the-road than before – but that this is not necessarily what comes across in the pictures of such events.

“If I see a guy with swastikas tattooed on his cheeks, I tend to hone in on him,” he says. “People who are middle class, who look reasonable and well-dressed are not so interesting.”

But with far-right parties now holding 10% of the seats in the European Parliament — compared with 5% in the 2014-19 session – it’s perhaps the wider appeal of such parties that is most disturbing. “People forget that Hitler came to power by democratic process in Germany,” says Steele-Perkins. “It wasn’t a coup, the people did it.”

Jérôme Sessini, meanwhile, argues it’s important to take a non-judgmental look at far-right protests, to try to understand what motivates people to adopt such views. He photographed far-right protests twice in 2016 in Dover – a town on Britain’s south coast whose geographical position has contributed to the arrival of both immigrants and anti-immigrant sentiment in recent years.

The images contain some shocking slogans and symbols – including National Front banners modelled on the Nazi flag – and their fair share of shouting, closely-shaved men. But, says Sessini, he aimed to show something more. “

“I was documenting the migrant camp in Calais, The Jungle, and I wanted to see what was going on in UK – the place where all the migrants are willing to go,” he explains.

“I just wanted to show another reality, the hunger of some people, people left behind who have chosen a radical way to express their despair. I wanted to show that there are some people who don’t believe that migration is a ‘chance’ for their country; people who are afraid of globalization ‘out of control’. I’m not judging them.”

When I ask if there’s a risk that by photographing such protests, he helps publicize or normalize them, he argues that “the risk is bigger if you do not show some realities, even those you don’t like.” He notes, “I’m not a publicist, I document.”

It’s a feeling echoed by both Steele-Perkins and Berry, with Berry retorting that he will “photograph anybody who interests me”, though adding that he finds the resurgence of the far right in the UK “rather disgusting”.

Steele-Perkins, for his part, says he got “a bit fed up with photographing skinheads”, though he adds the he could continue doing so “because it’s still going on”. Recently he’s undertaken a project focusing upon the other side of the story of multiculturalism in the UK, this time in much broader terms, working on a huge project titled The New Londoners. The work, which was made over four years, saw Steele-Perkins photographing individuals and families from 187 countries around the world who have made London their home. “I hope it’s a more nuanced way of dealing with immigration,” he says.

He adds that he doesn’t believe photography can change anything – but that he does believe it can it can stand as a record, and he hopes that The New Londoners will do just that in the future. By the same logic, he also defends photographers’ right to photograph far-right supporters, even if the sentiment they’re interested in shooting is not always visible.

“I think one should do it to keep people informed if nothing else,” Steele-Perkins says. “But I guess I’m not that interested in doing it. I find the company difficult to keep.”