The Spanish Civil War: The Catalonia Offensive

This January marks 80 years since the fall of Barcelona to nationalist General Franco's troops in the Spanish Civil War

Before he would go on to co-found Magnum, Robert Capa made his name photographing the Spanish Civil War. In an era when photojournalists weren’t often credited for their work, 1938 saw Picture Post taking the unprecedented step of introducing him, along with his Spanish Civil War work, as “the greatest war photographer in the world”.

The photographs taken by Capa and his partner Gerda Taro captured the brutal realities of combat. Photographic coverage of the Spanish Civil War was an emotional investment for Capa; ideologically, he sympathized with the plight of the anti-fascist Republicans, consisting of the workers, the trade unionists, socialists and the poor.

On December 23, 1938, the Nationalist Army started an offensive that rapidly conquered Republican-held Catalonia. Barcelona – the Republic’s capital city from October 1937 – was eventually captured on January 26, 1939. The Republican government headed for the French border and safety, and thousands of people fleeing the Nationalists also crossed in the following month, to be placed in internment camps. Franco had closed the border with France by February 10, 1939.

The following extract from the essay Robert Capa in Spain, by the late photography writer Richard Whelan, from the book Heart of Spain: Robert Capa’s Photographs of the Spanish Civil War, published by Aperture, details these the pivotal events of December 1938 through to the dramatic conclusion of January 1939 – which would become known as The Catalonia Offensive – and the immediate aftermath.

In 1936, the rebellion of monarchists and fascists led by General Franco, in alliance with Hitler and Mussolini, mobilized anti-fascists all over the world, among them Robert Capa. During the entire period of the civil war, Capa traveled throughout the Loyalist-held areas of Spain, photographing battles, cities under siege, and the chaos of a modern nation at war with itself. One series of images documents the heroic Loyalist defense of Madrid; another the mass exodus of Catalonians from Barcelona to the French border. His iconic photograph of a Loyalist militiaman who has just been shot shocked the world with its brutal immediacy. Capa’s pictures not only illuminated the strength and courage of the soldiers who carried on against overwhelming odds but also galvanized compassion for the innocent and injured. John Steinbeck praised Capa for his ability to “show the horror of a whole people in the face of a child.”

Capa spent most of the first nine months of 1938 in China. When he finally returned to Spain, in October, the news was bad. In an attempt to win Hitler’s friendship, Stalin had ordered the International Brigades to disband, thereby more or less guaranteeing victory to Hitler’s ally Franco. On October 16, in the hills near Falset, a few miles east of the Ebro River, Capa photographed the men of the brigades as they marched in their final review.

On October 25, Capa, in the company of fellow photographer and close friend David Seymour (also known as Chim), drove out to Montblanch, where government and military leaders were to bid farewell to a large delegation of volunteers of all nationalities. Capa focused on the men’s strong faces, whose sadness reflected their certainty that the departure of the brigades would mean the Republic’s defeat. Four days later he and Chim covered Barcelona’s exuberant but bittersweet farewell parade for the volunteers.i

On November 5, Capa and Hemingway drove out to Mora de Ebro and crossed the treacherous Ebro River in a small boat to spend a day with General Lister and his fifth Army Corps, which was barely holding out against a major Nationalist offensive.ii

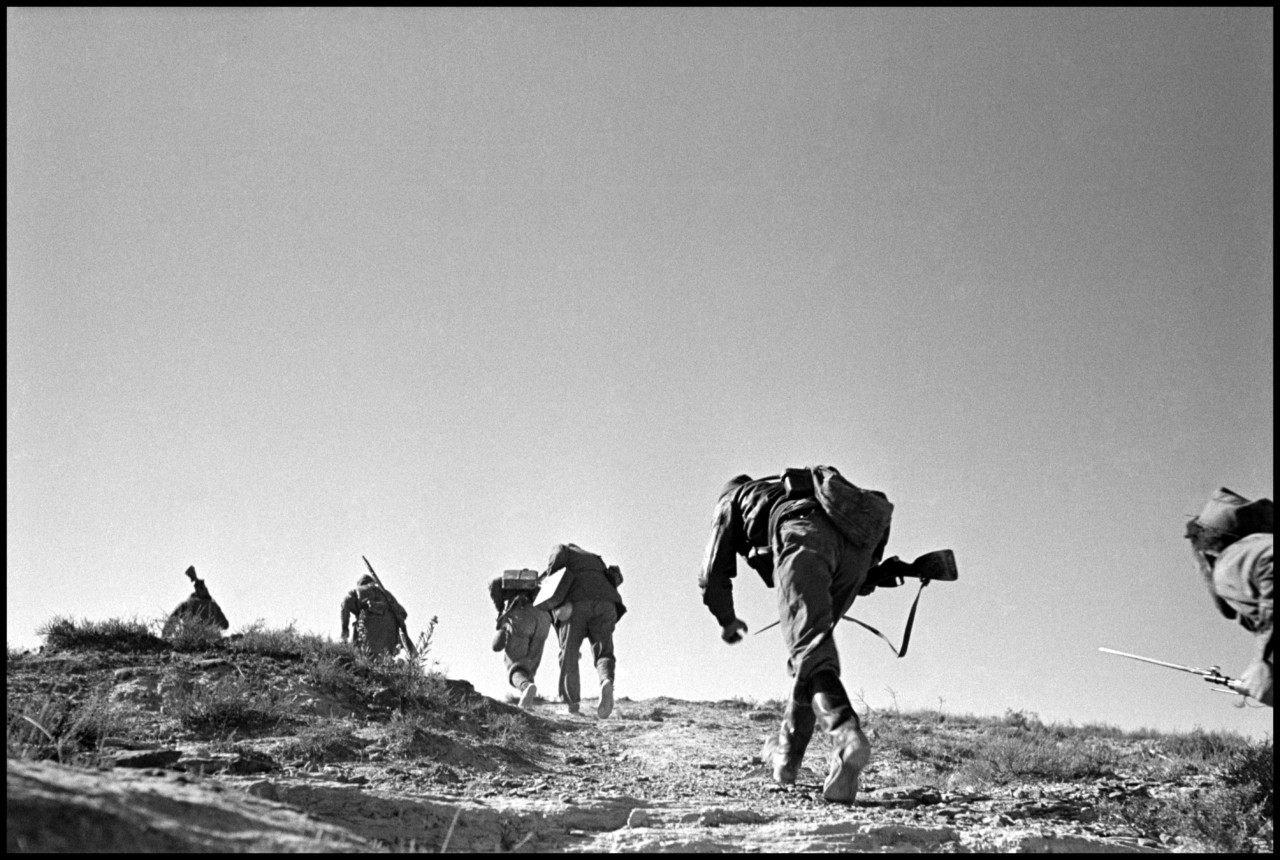

The next night, in an effort to divert the Nationalists from the battle at Mora de Ebro, Republican troops waded across the Segre River, a tributary of the Ebro, some forty miles to the north. When word of the offensive reached Barcelona early on the morning of the seventh, Capa headed straight for the front. He found it Southwest of Urida, near the town of Fraga, where the fighting was especially heavy. In this barren, rocky, hilly terrain, as thousands of men made a last, futile attempt to thwart the imminent Nationalist victory on the Ebro, Capa made some of the most dramatic frontline battle photographs of his entire career. Looking at them, we can almost believe that we can smell the acrid fumes of gunpowder and feel the earth shaking as shells explode nearby. iii

Life gave the story two pages; Regards gave it five pages and the back cover; and Stefan Lorant’s new British magazine, Picture Post, devoted eleven pages to the photographs, calling one of them (of several men taking refuge under a rock overhang as shells explode close by) “the most amazing war picture ever taken.” The magazine prefaced the story with a nearly full-page photograph of Capa.

When Capa returned to Spain, around January 10, 1939, he went to the Catalonian front to photograph General Lister and his men, but there was a lull in the fighting, and thereafter he remained in Barcelona.

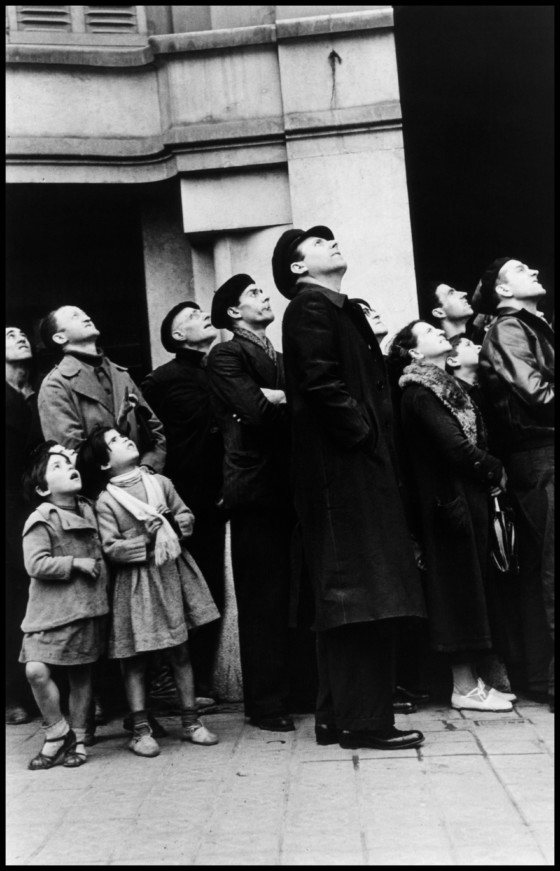

Although some hoped that the city might follow Madrid’s heroic example in defending itself, the realists correctly surmised that the hungry, exhausted, poorly armed city, which was now being heavily bombed, could offer little resistance.

During the night of January 12, Barcelona was plastered with posters announcing the general mobilization of all men up to the age of fifty for the defense of Catalonia, and by noon on the thirteenth the mobilization centers were filled to overflowing. That afternoon Capa went to one such center, a stadium on the outskirts of town. In his poignant series of photographs of the men with their families, he captured the fear, the gravity and the resignation of the farewells.

"I have seen hundreds of thousands flee"

- Robert Capa

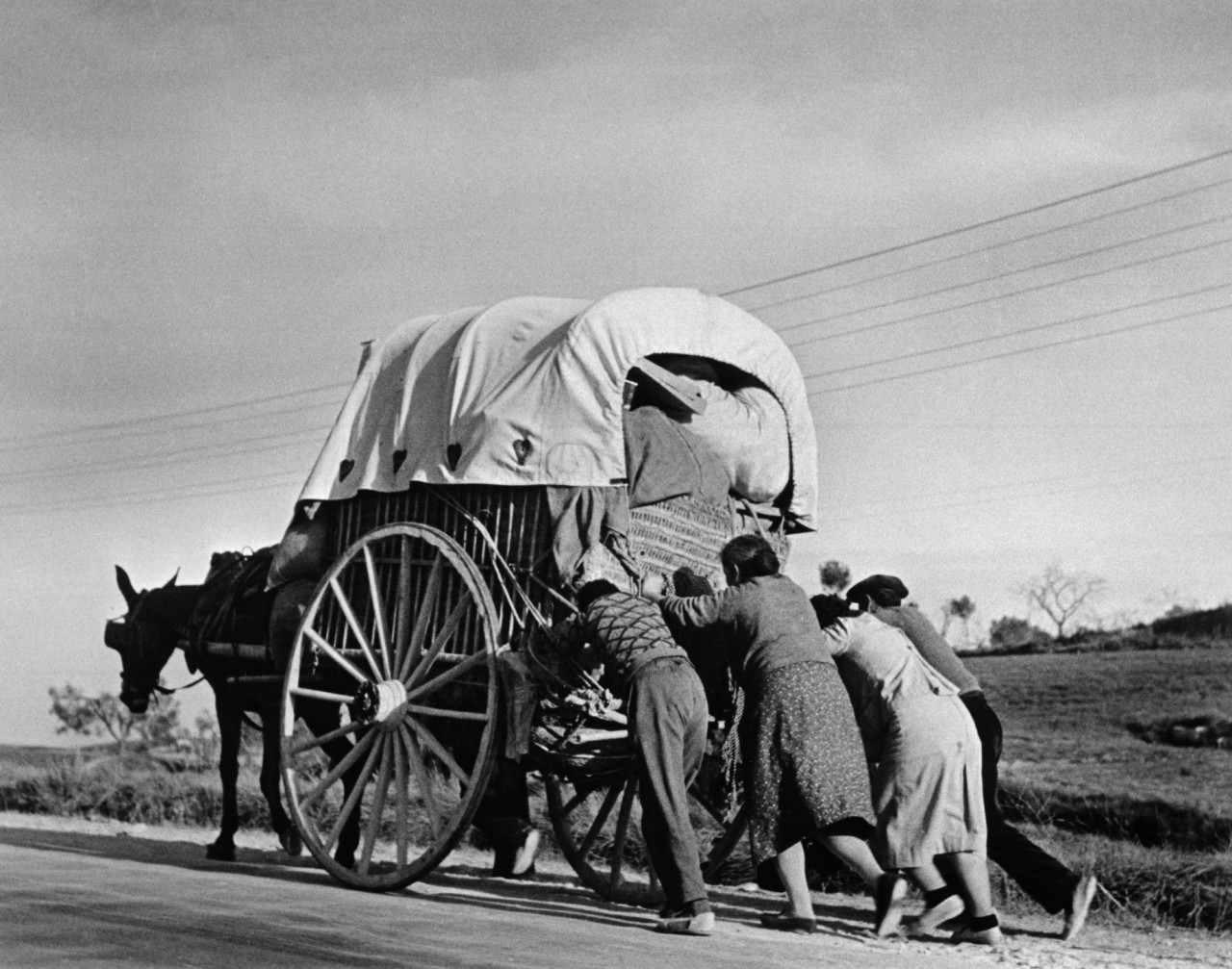

Two days later, on January 15, Capa was out on the coastal road south of Barcelona photographing the refugees who had waited until the last minute to abandon Tarragona. Some had piled so many possessions onto their carts that they had to help the emaciated mules by pushing from behind. Suddenly, planes swooped down over the road to machine-gun the helpless refugees. Among the most harrowing of the photographs Capa took that day was a series that show [sic] an old woman who miraculously survived unscathed an attack that killed everyone else in her group as well as her dog and her two mules. Capa found her circling her cart endlessly in a state of uncomprehending shock.iv

To accompany his reportage, Capa wrote:

I have seen hundreds of thousands flee thus, in two countries, Spain and China. And I am afraid to think that hundreds of thousands of others who are yet living undisturbed peace in other countries will one day meet with the same fate. For during these last three years that is the direction in which the world we wanted to live has been going.v

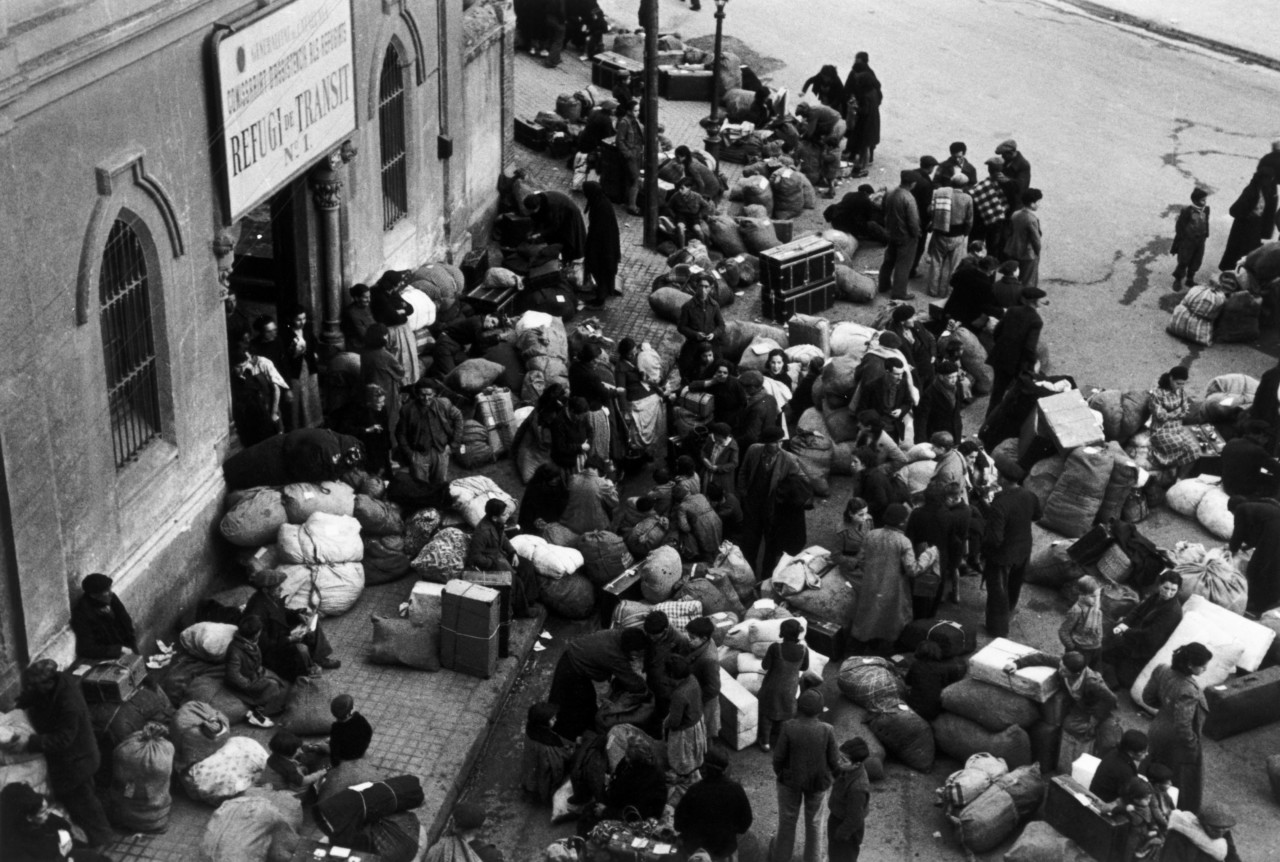

A few days later, after describing a beautiful, dark-eyed young girl he had photographed as she sat despondently on a pile of sacks in front of a Barcelona refugee center, he wrote, “It is not always easy to stand aside and be unable to do anything except record the sufferings around one.”vi

"It is not always easy to stand aside and be unable to do anything except record the sufferings around one"

- Robert Capa

By January 21, Heinkel bombers had become an even more familiar and dreaded sight than ever in the skies over Barcelona. Often a respite of no more than fifteen minutes separated the raids, day and night. Then, at about one o’clock on the morning of Wednesday, January 25, arrived the alarming news that the Nationalists had already crossed the Llobregat River, less than ten miles to the west. Capa and several other correspondents piled into their car and drove north on the coastal road to Figueras, the last major town before the French border. One of Capa’s companions wrote that they “overtook thousands and thousands of refugees, in carts, on mules, afoot, begging rides in trucks and cars, and always wearily struggling forward to that inhospitable frontier which still remained grimly closed to them,” for the French has not yet agreed to allow the refugees to enter France.vii

Capa spent the next several days in Figueras, photographing refugees in the town and on the nearby roads. On January 28, Capa crossed the border along with some of the first of the four hundred thousand men, women and children who were eventually to leave Spain.

While he was in London in February, word came through that the French government (which until then had admitted only Spanish civilians) had finally decided to allow the retreating army of two hundred thousand Republican soldiers to cross the border, though they would be held in internment camps near Perpignan. Lorant immediately assigned Capa to do a story for Picture Post about the camps, but the photographer could not yet bear to face the humiliation that his Spanish comrades were having to endure at the hands of the French, who, he later wrote, “received the exhausted Spanish refugees with the cruel indifference of the people who are warm and well fed.”

Excerpted from the essay “Robert Capa in Spain,” copyright Richard Whelan, © 1999. From the book, Heart of Spain: Robert Capa’s Photographs of the Spanish Civil War from the Collection of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, copyright Aperture Foundation © 1999

————-

[i] Regards, October 27, 1938, pp. 6–7 & back cover; November 10, pp. 12–13; November 17, p. 9. Ce Soir, October 29, 1938, p. 8; November 15, p. 8; Picture Post, November 12, 1938, pp. 34–37.

[ii] Herbert Matthews, The Education of a Correspondent (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1946).

[iii] Regards, November 24, 1938, pp.11–15 & back cover. Picture Post, December 3, 1938, pp. 13–24. Life, December 12, 1938, pp. 28–9.

[iv] Ce Soir, January 22, 1939, p. 8. Picture Post, February 4, 1939, pp.13–19.

[v] Original typescript in German. Capa Archives, International Center of Photography, New York.

[vi] Original typescript in German. Capa Archives, International Center of Photography, New York.

[vii] Herbert Matthews, op. cit. Ce Soir, January 29, 1939, pp. 1 & 8; January 30, pp. 1& 8; January 31, p. 8. Regards, February 2. 1939, pp. 9–13. Match, February 2, 1939, pp. 9–14. Collier’s, February 4, 1939, pp. 12–13.