House of Bondage Revisited

As Aperture releases a new edition of Ernest Cole's influential 1967 classic, Colin Pantall reflects on the powerful directness of its message and how its legacy was felt by those who followed.

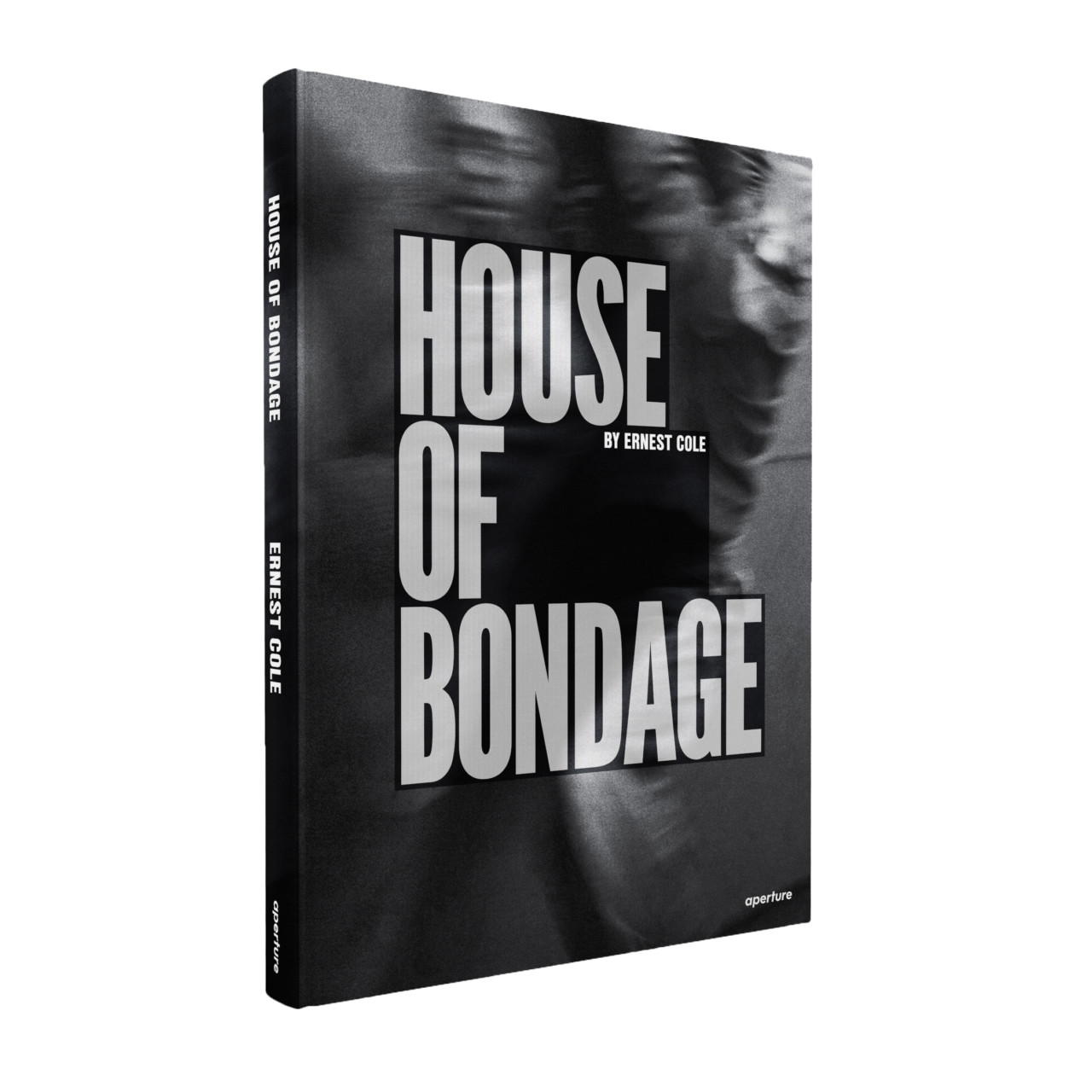

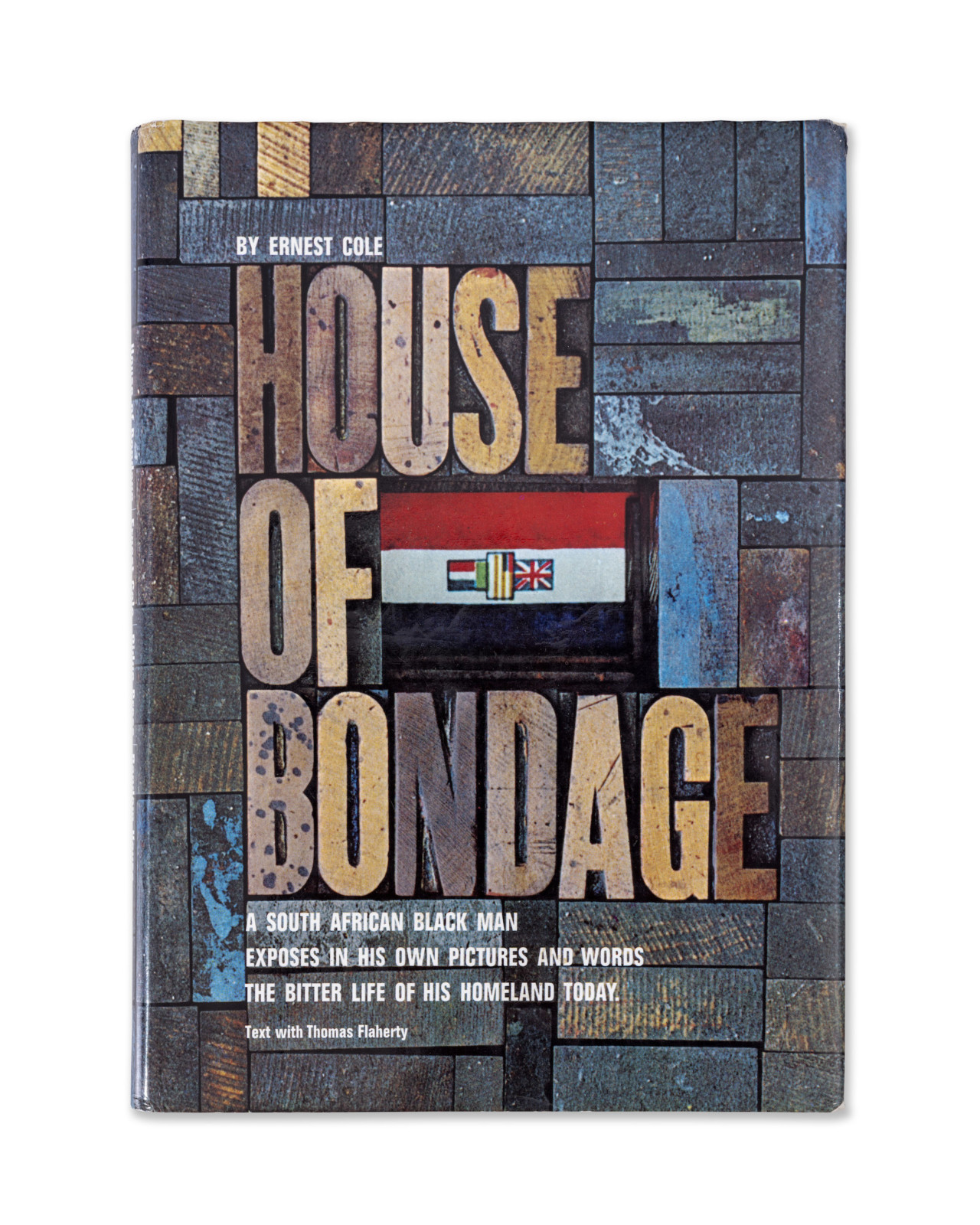

Aperture’s new edition of Ernest Cole’s important and influential 1967 book, House of Bondage, is not too different from the original. There are a few additional images, some added texts, but that’s about it – deliberately so.

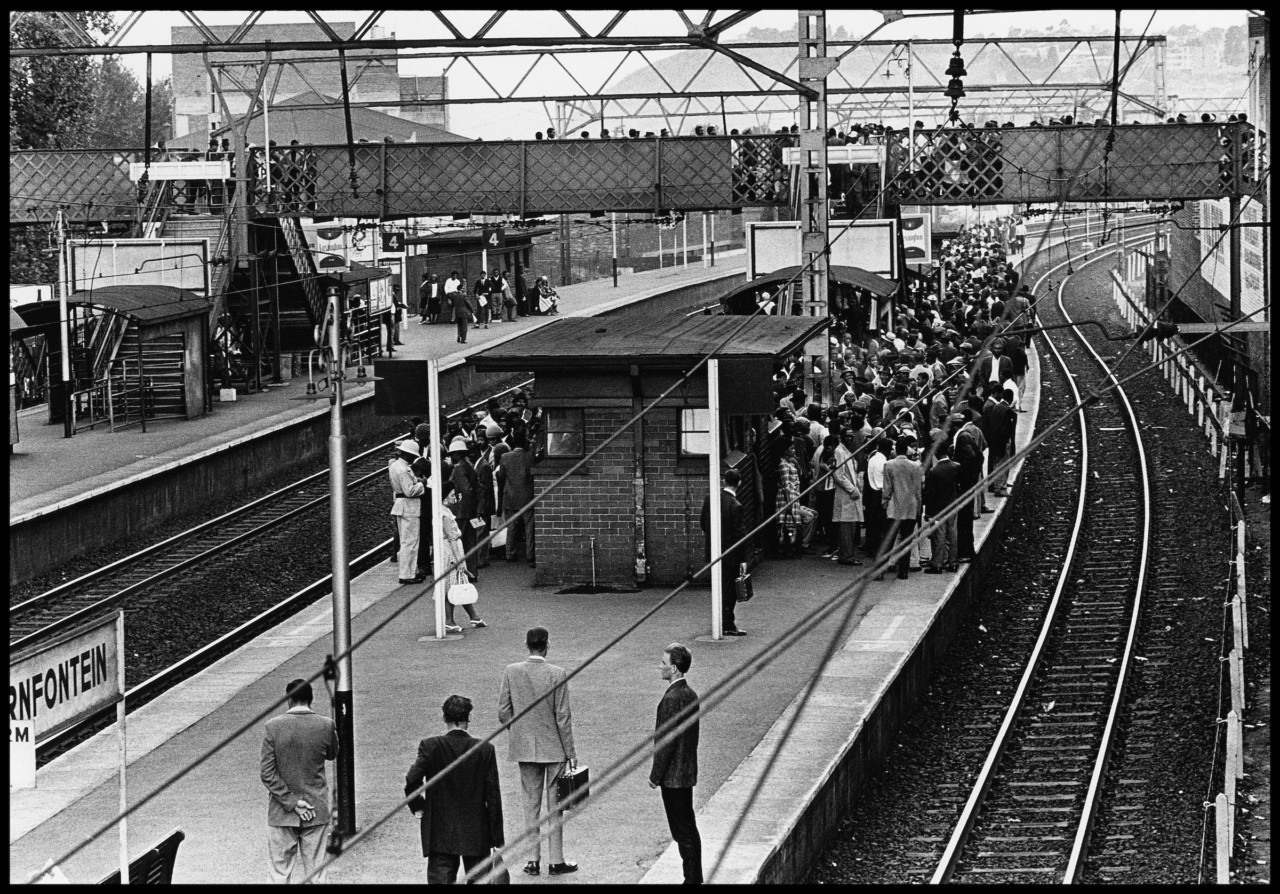

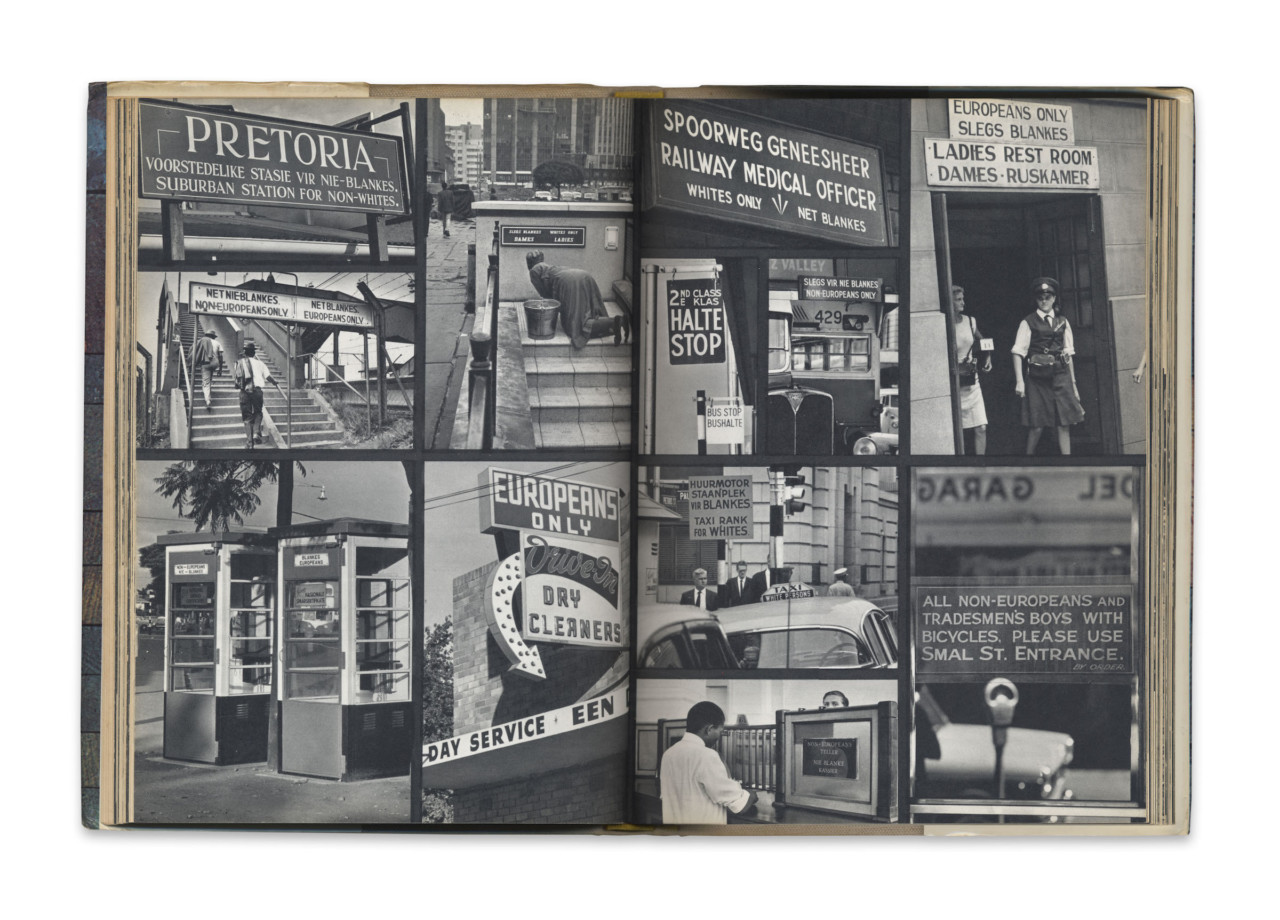

The cover has changed from color to a sober black-and-white image and text. On the original inside cover there was a double-page-spread of Cole’s iconic picture of a South African train platform, distilling the structural division between white and black; one side populated by just seven commuters, the other side crammed edge-to-edge. In its place is a grid of pictures from the original contact sheet showing variations on the same theme. This, if anything, is even more devastating as we see both sides of the platform, and the sea of space that is available to the white travelers.

The message is direct. There is no room for ambiguity or misunderstanding. Right from the start you know that this is a book about the evils of apartheid; about its racism, its injustice, and the way in which it is so easily grasped by those who it always benefits in terms of health, housing, education, work, transport, food, everything. There are no two sides to this story. There is one side, and it’s the side that Cole tells.

The Aperture edition of House of Bondage is available in the Magnum shop.

Open the book up and you come to some new writing. Oluremi C. Onabanjo writes on how Cole saw the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson and was inspired to make his House of Bondage work. “I knew then what I must do,” he said. “I would do a book of photographs that would show the world what the white South African had done to the black.”

In On Looking at House of Bondage: A Lament, an Indictment, Mongane Wally Serote wonders how it is possible that, despite the depictions of Cole, and the howls of outrage and horror, it is possible that such conditions still exist in South Africa and beyond. “Human beings consciously and deliberately founded the apartheid system, colonialism, imperialism. People who sit in air-conditioned high-rise offices plot for these conditions to be a reality for other human beings because the countries of those, the subjects of the Coles of the world in Africa, Asia, Latin America, happen to be endowed abundantly with natural resources.”

The apartheid system is the formal structure that was the foundation for what the white South African did to the black. It segregated the nation into whites, coloreds, and blacks. Whites were rewarded for their whiteness, blacks were punished for their blackness.

That exposition of the apartheid system is evident in the contents page. There are 14 sections, including chapters titled, ‘The Mines,’ ‘Police and Passes,’ ‘Nightmare Rides,’ ‘For Whites Only,’ ‘Education for Servitude,’ and ‘Banishment.’

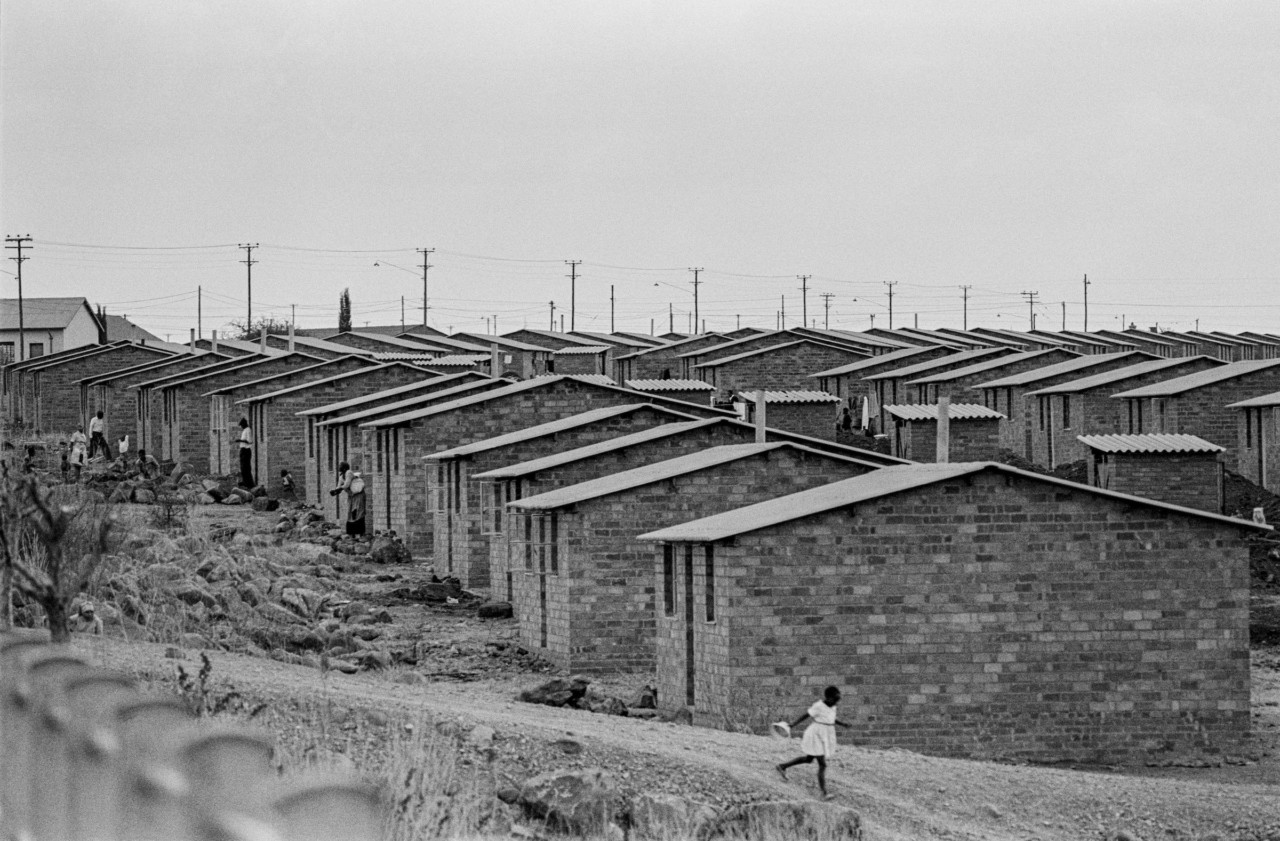

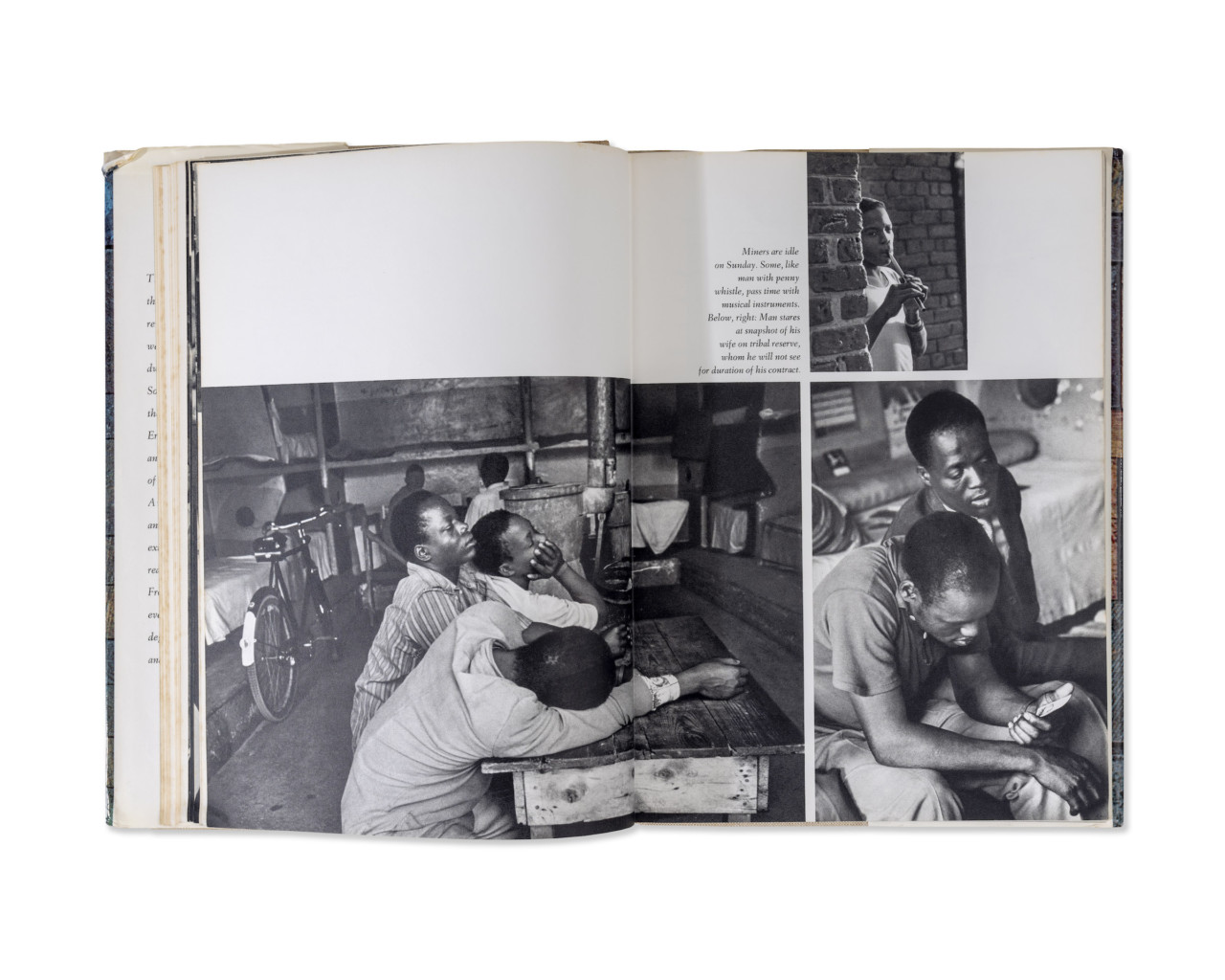

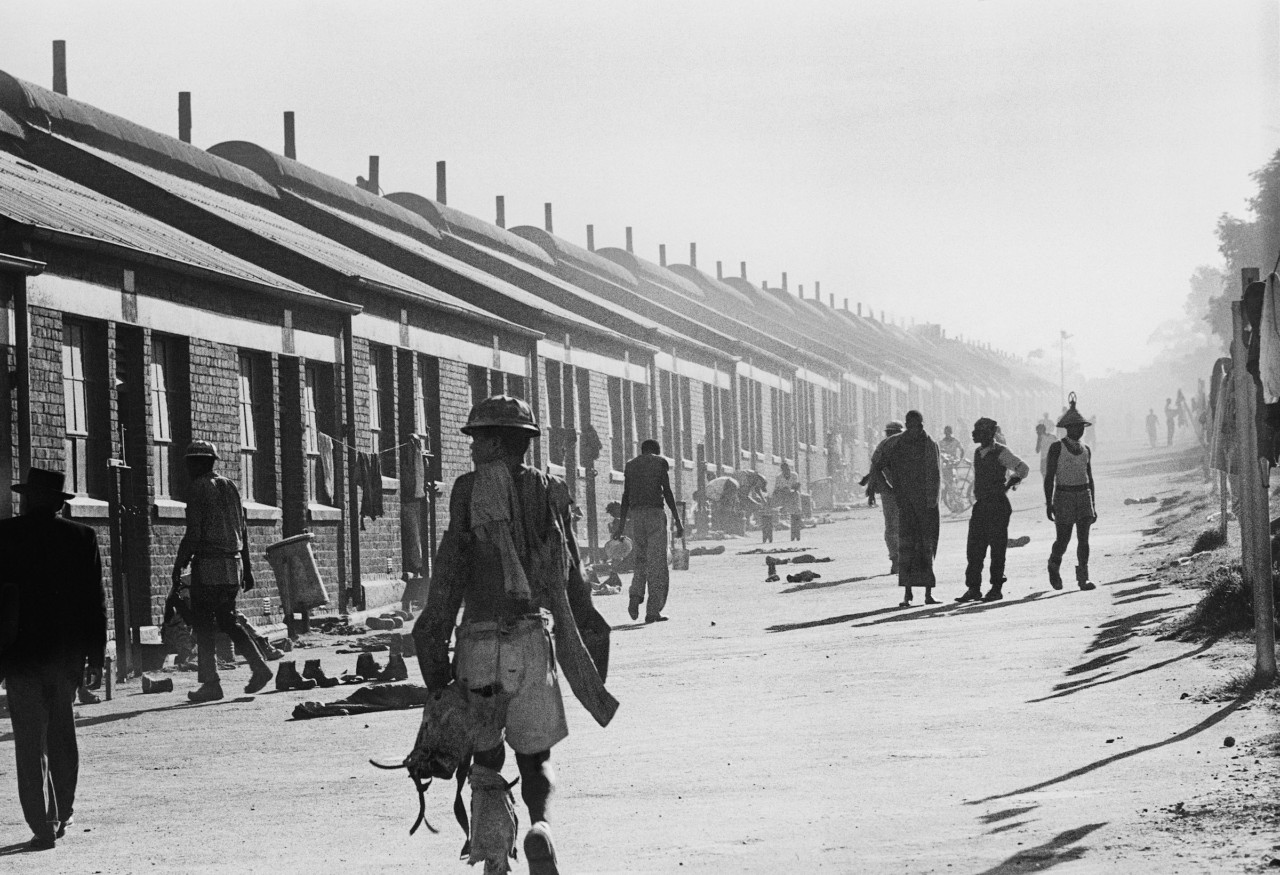

These chapters show the interconnectedness of the apartheid regime. The pass system (legislating where blacks could and, more importantly, couldn’t live) links in to the mines, and transport links in to housing, which was often built at a distance from places of employment so that the exhaustion of work would be compounded by the exhaustion of travel, leaving no space for political thought or activism. Everything is connected.

"I knew what I must do. I would show the world what the white South African had done to the black."

-

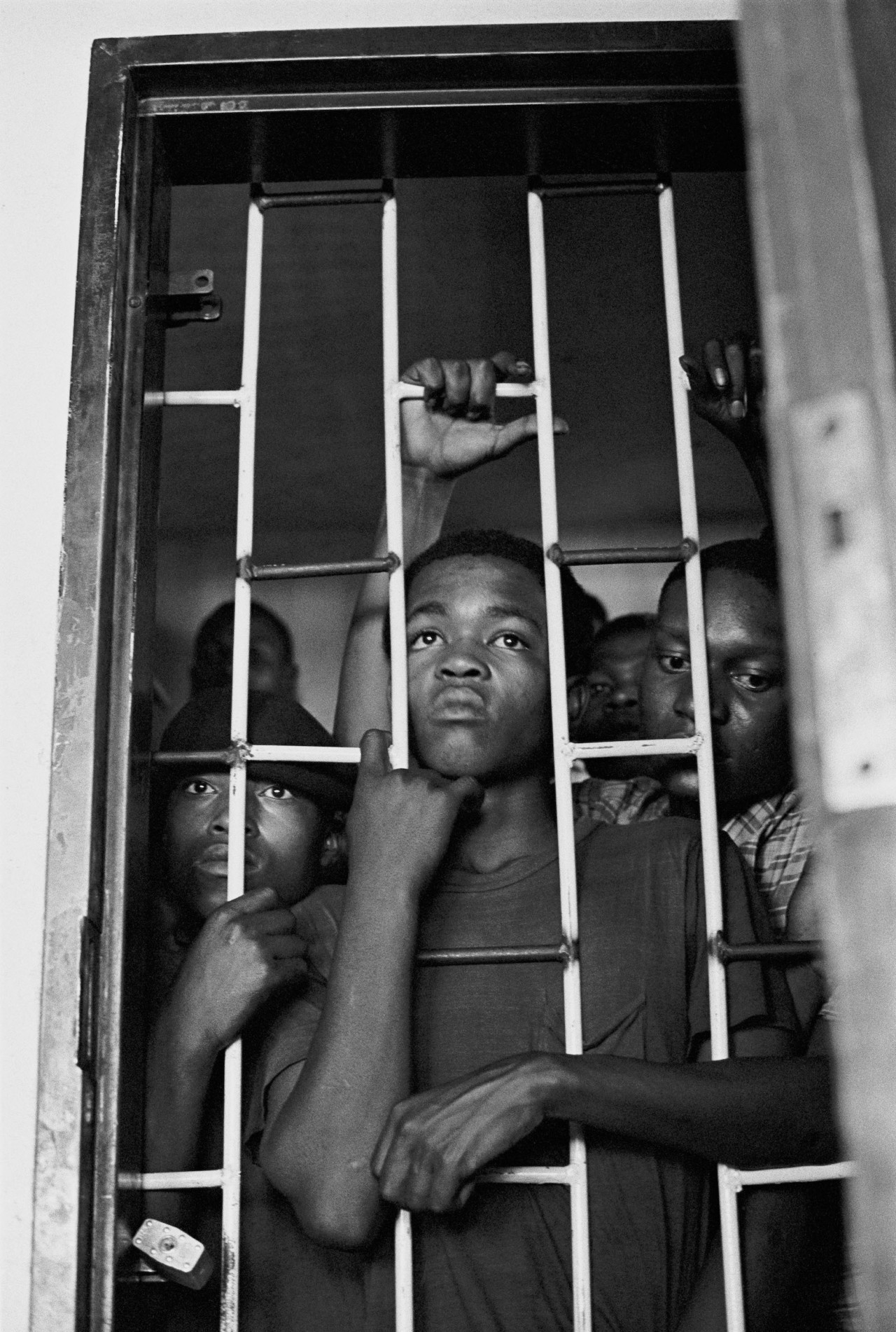

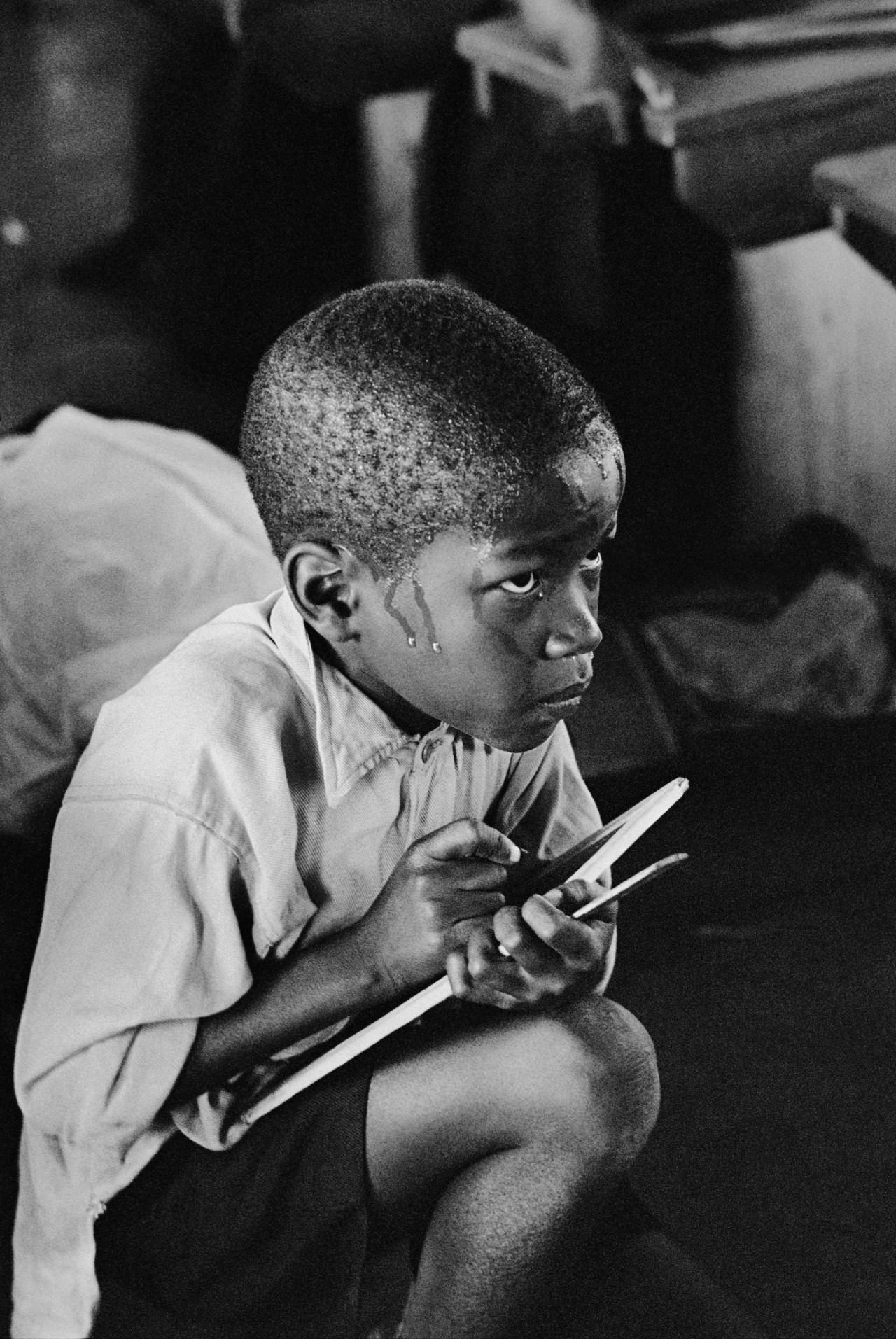

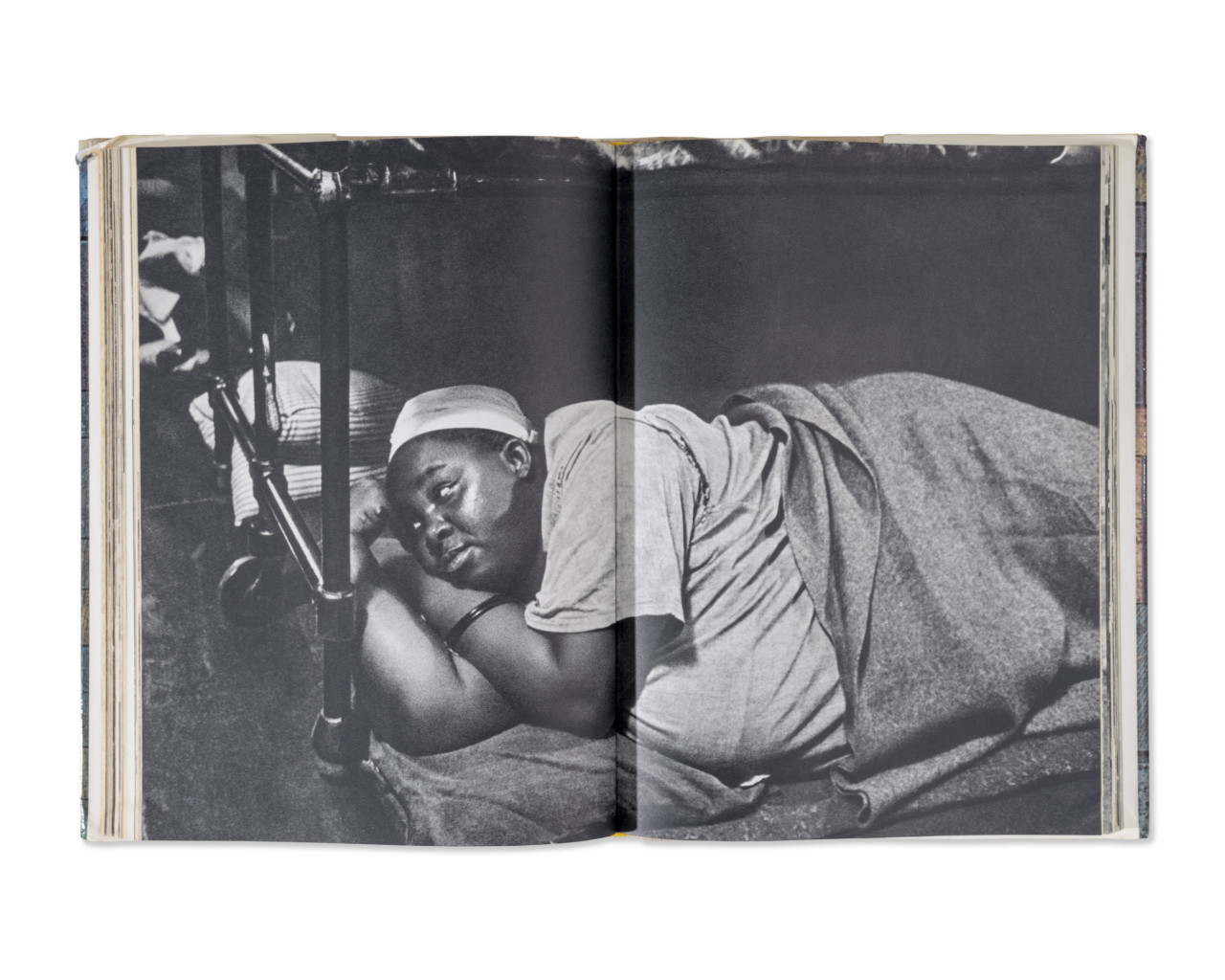

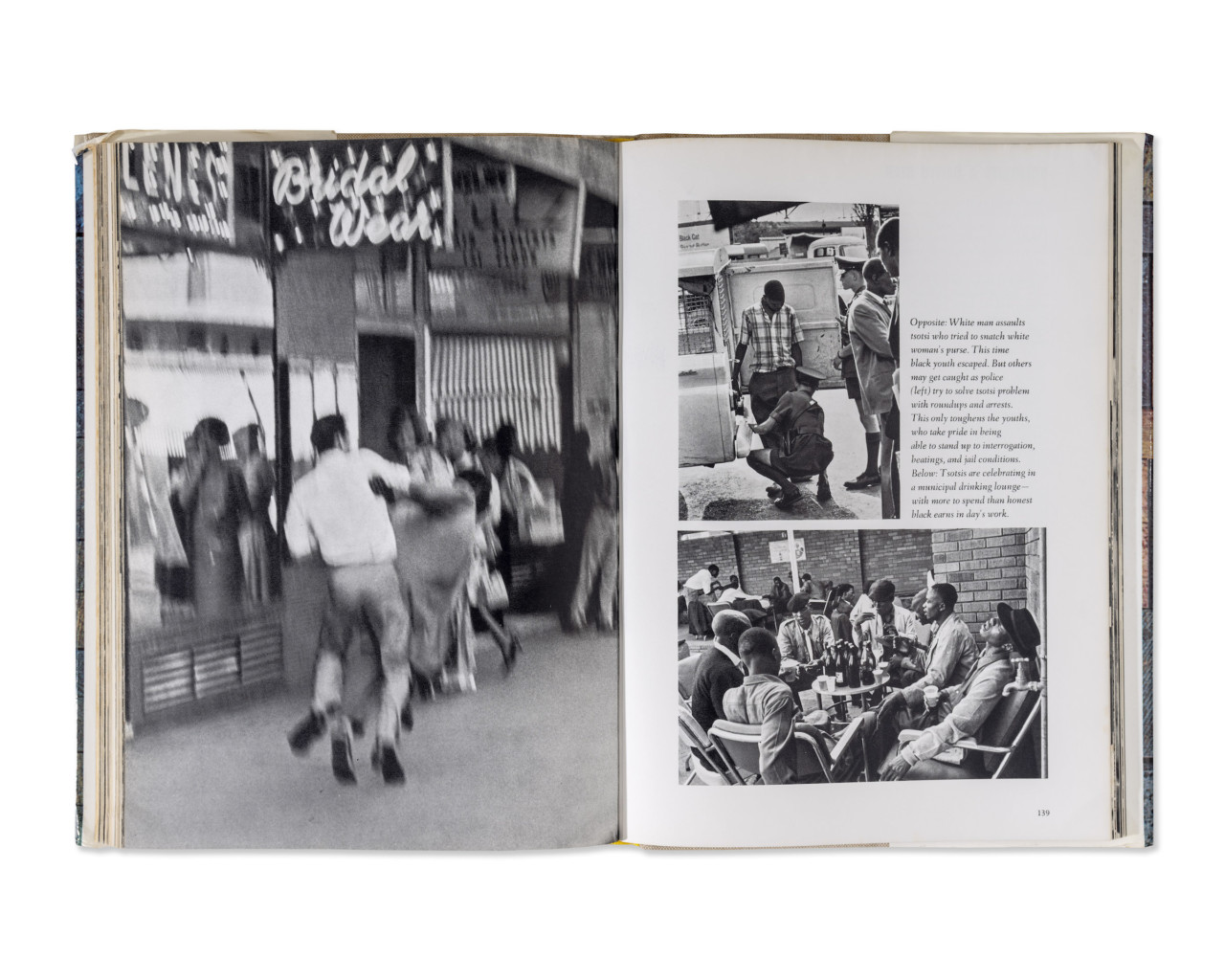

Serote writes about “…something in the being of those captured by Cole’s camera is always revealing of the utter rejection of their state of affairs. The impact of the brutality is expressed through their frozen silence, as it is also, the loudest rejection of their state of affairs.”

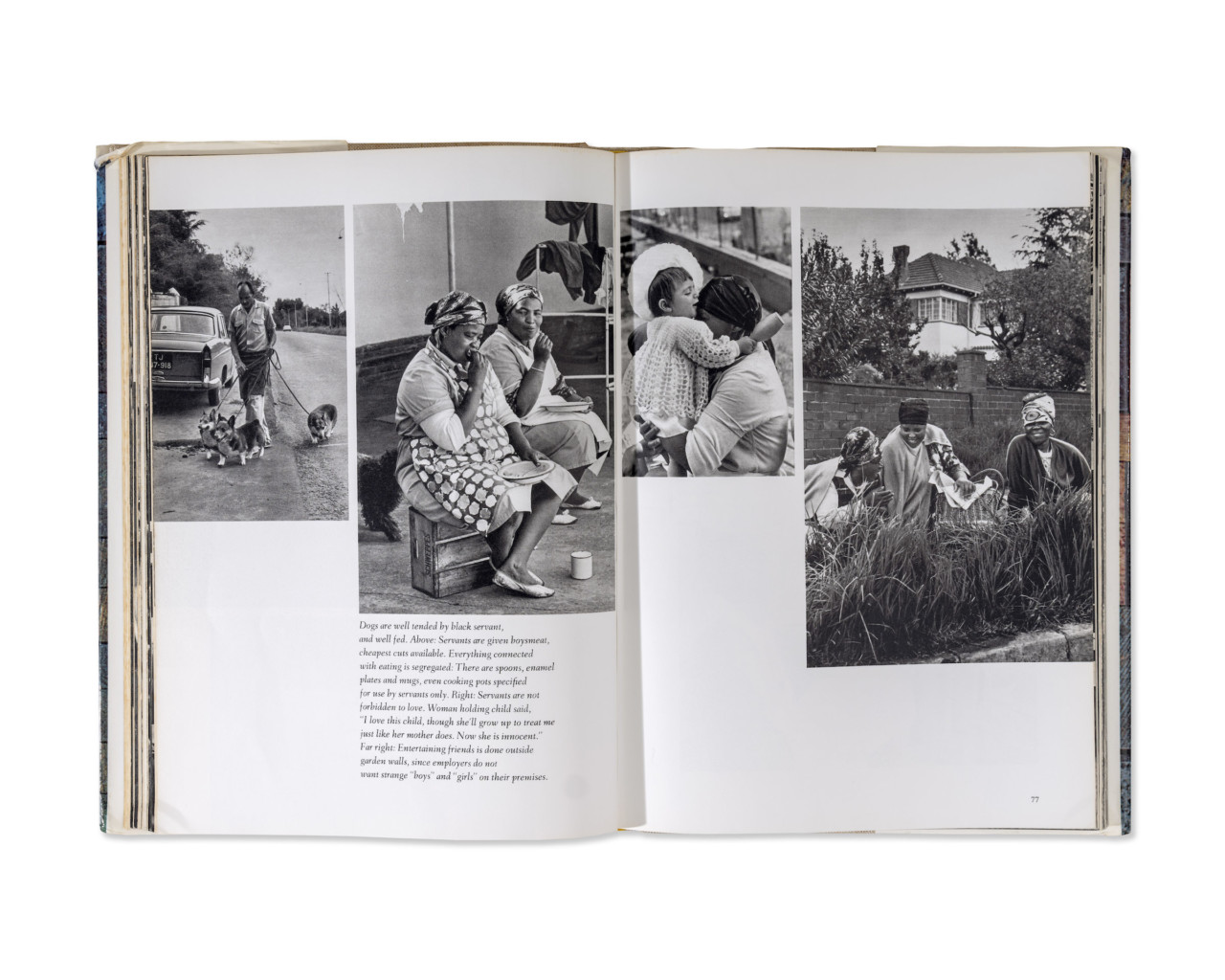

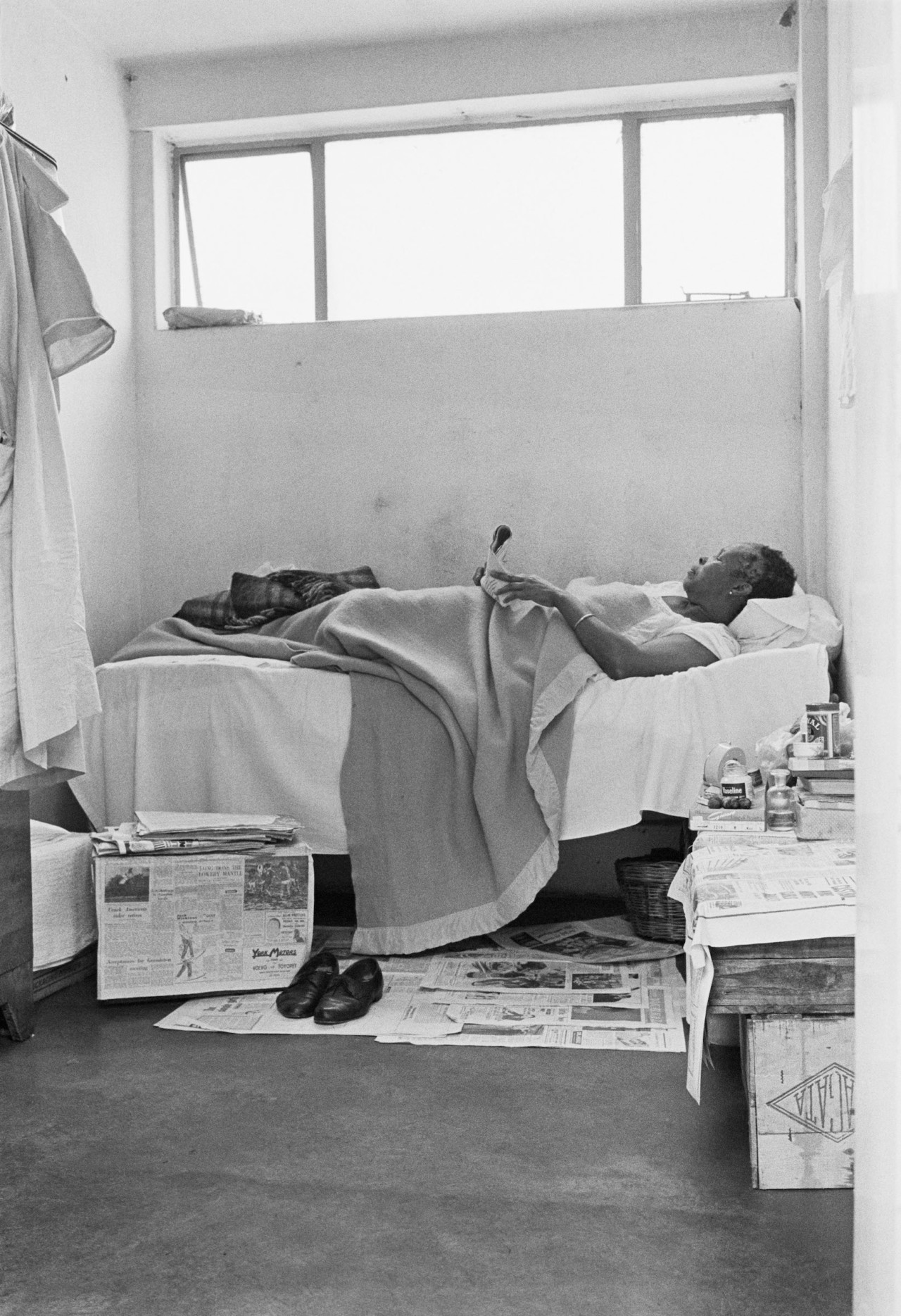

You can see this in the faces of black commuters packing onto trains to travel from the townships to their places of work in cities they are not allowed to live; in his pictures of black servants who are not allowed to live under the same roof as their white employers; in the faces of people queuing from early morning to see a doctor who will decide if you are allowed to be admitted and be treated under a policy of ‘calculated neglect’.

Inequality is enacted in schools where black pupils get 10 per cent of the funding of white pupils. “When I have control of native education,” said Dr. Hendrik F. Verwoerd (a future prime-minister) in 1953, “I will reform it so that natives will be taught from childhood to realize that equality with Europeans is not for them.”

The classes are packed into whatever ramshackle structure is available. Teachers are shown running classes of a hundred. Schools are shown lacking in basic furniture and equipment as exhaustion overtakes both pupils and teachers struggling to cope in a deliberately made to be incompatible with learning.

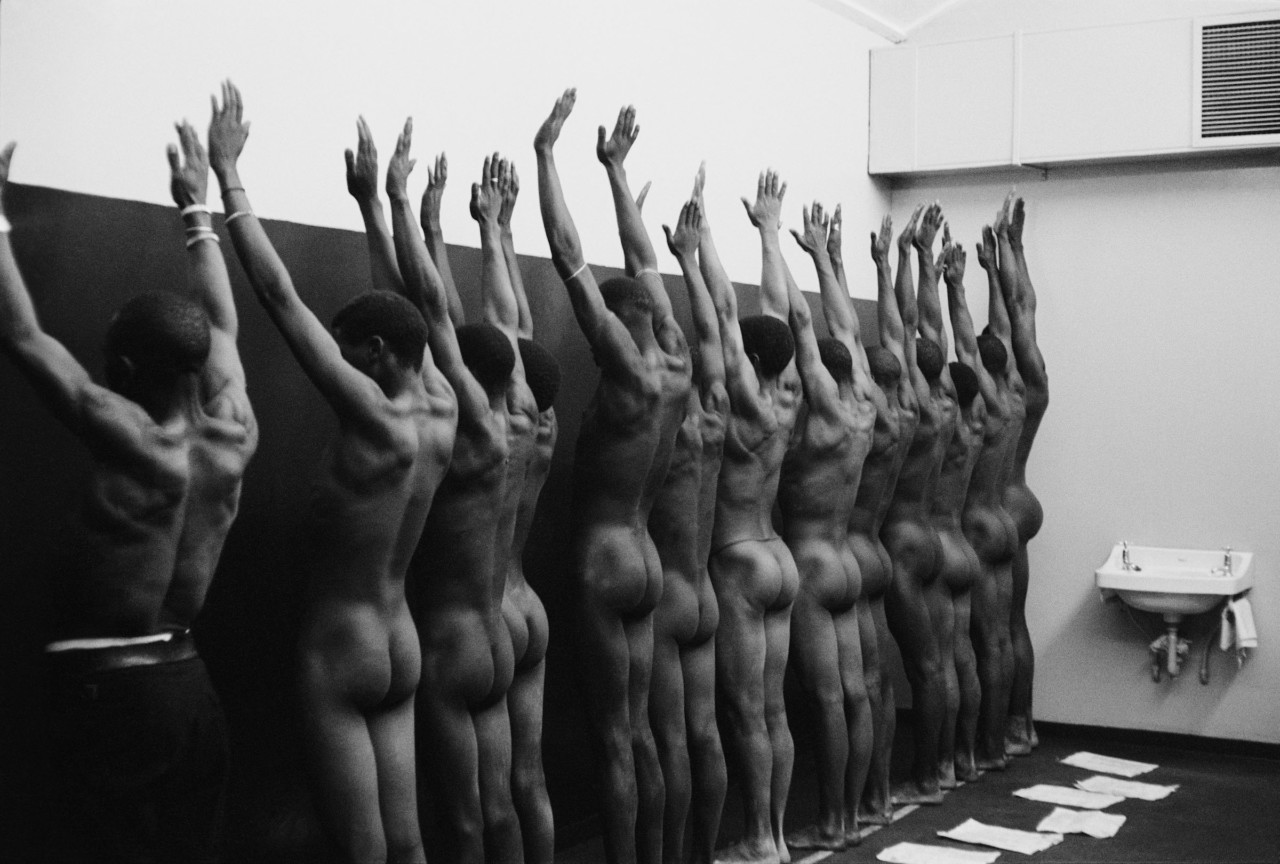

Some of Cole’s most devastating pictures were made in the gold mines. His image of a medical examination of black miners standing naked with their hands raised captures the dehumanization they underwent in their working conditions, their food and lodging, and their contracts.

James Sanders writes that “there is no doubt that Cole prided himself on his ability to retain a level of invisibility as he swiftly raised and lowered his camera to his eye. It has been claimed that in the mines he hid his camera in a paper bag under a sandwich and photographed through a small rip in the paper.”

The ability to photograph at all came from Cole being able to change his racial classification from black to colored, something almost impossible to do in a nation led by a white elite with an unwavering belief in eugenics – a change that coincided with him changing his name from Kole to a more European-sounding Cole.

In 1966 Cole went into exile, ahead of House of Bondage being published the following year to international acclaim. The book was banned in South Africa, but sold out elsewhere, revealing the horrors of apartheid to the world for the first time, its chaptered image sequences clearly describing the interconnected oppressions of apartheid.

"The message is direct. There is no room for ambiguity or misunderstanding."

-

House of Bondage would influence generations of photographers around the globe. Its defining message is apparent in books like Philip Jones Griffiths’ Vietnam Inc., published in 1971, using titled sections that highlighted the Kafkaesque nature of the war and its rationalizations. It used the design language of color supplements for its layouts, accompanying them by a direct and very sarcastic text that is directly connected to that of House of Bondage. One image shows a woman and her baby “shortly before being killed”, another shows the computer that ‘proves’ the Americans are winning the war, another an American marine “winning hearts and minds” by “demonstrating to bored mothers how to bathe a baby.”

There is a glossary of language at the beginning of Vietnam Inc. that owes much to Cole’s interest in the language of apartheid, as evidenced directly in his image-texts of signs above segregated entrances, exits, benches, clinics, train platforms and telephone boxes, but also indirectly in his interest in the euphemisms of racism. Cole writes about on boysmeat (the second rate cuts and offal bought for black servants) and location (the vague term used to describe the home of people who are given only vague human status under the laws of apartheid).

Head forward in time and you can link the unambiguous messages of Laia Abril’s On Misogyny series or Mathieu Asselin’s Monsanto to House of Bondage. Again the purpose is not to show a balanced argument, or to get all sides, because there is only one side. It’s a complex side and it has multiple dimensions, but ultimately the purpose of the work is to highlight injustice, cruelty, and the imbalance of power.

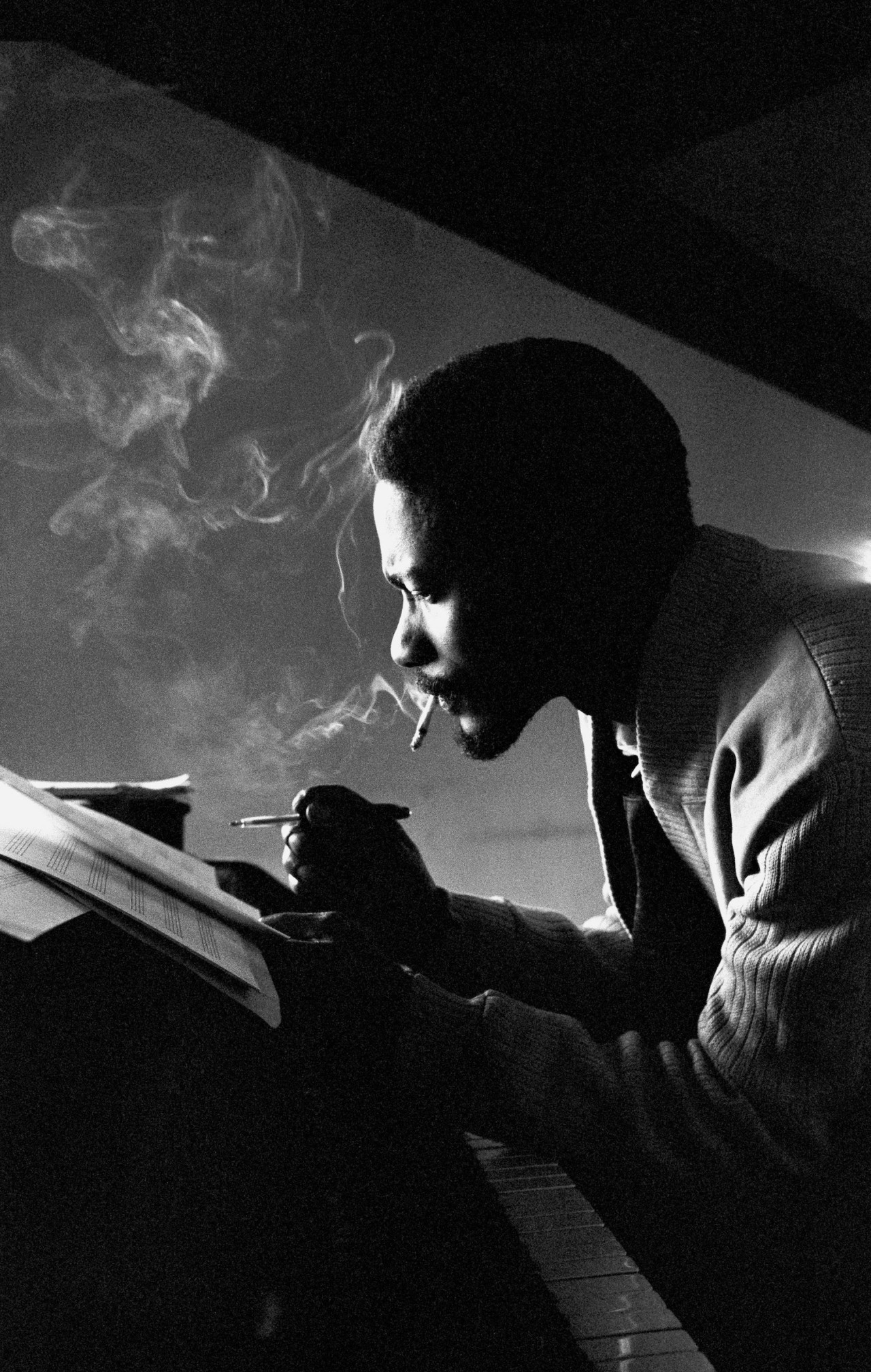

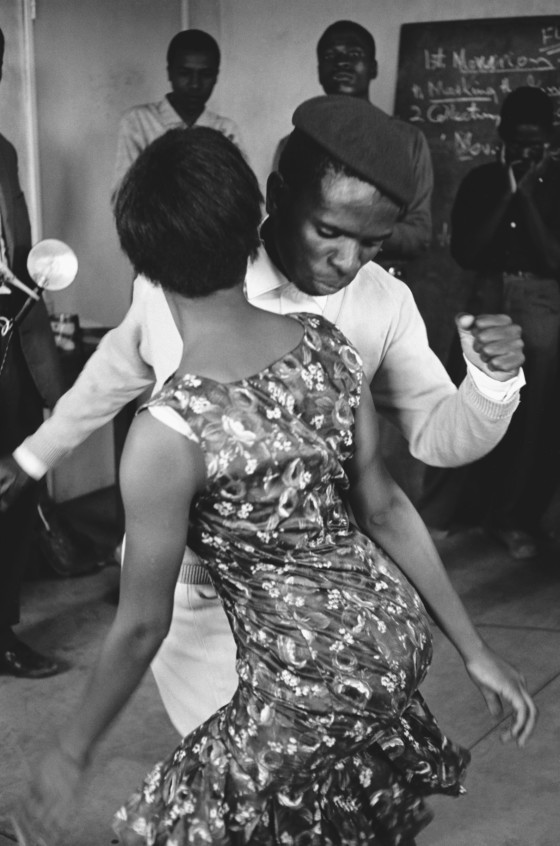

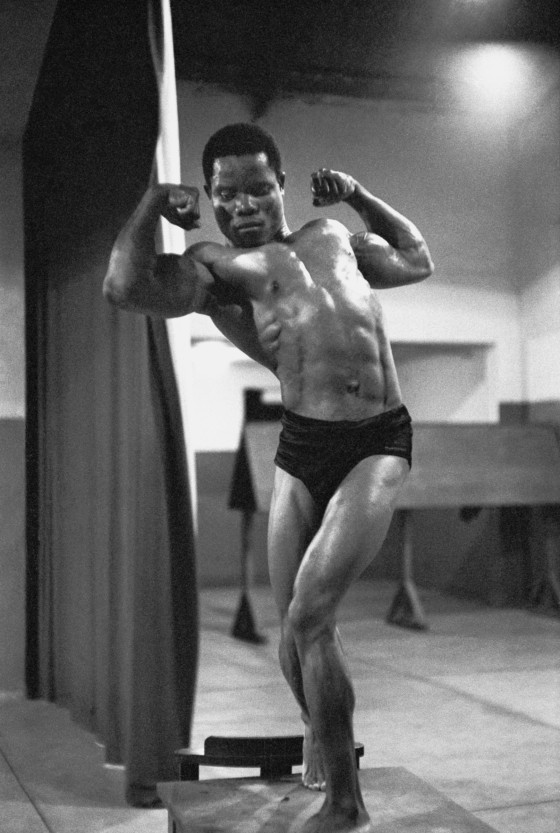

The book ends with a new addition; a series of images that Cole had loosely entitled ‘Black Ingenuity’. It highlights the creative power of black South Africans, showing what is possible even within the structures of racist and economic injustice, making visible the musical and artistic potentials that white South Africa was trying to hide or erase. He shows the places where musicians like Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba practiced, where the hugely popular King Kong, the “all-African jazz opera,” was developed. It’s a complex chapter where black creativity comes up against the contradictions of white patronage.

And this is perhaps where Ernest Cole’s influence is most powerful, in helping encourage a new group of South African photographers to express themselves with that same directness and clarity of vision. Perhaps Zanele Muholi and their call to visual activism and an acceptance of queer identities is the most notable of these photographers, but Peter Magubane, Santu Mofokeng, David Goldblatt, Sabelo Malangeni are others are mentioned by Onabanjo as making work which Cole’s “commitment to the photographic medium” contributed to.

South African Magnum member, Lindokuhle Sobekwa, directly cites Cole as an inspiration. House of Bondage was the first photobook by a black South African that he had ever seen, and he became “obsessed” by the book and its power to tell a nuanced story that connected both personally and politically. “As a ‘born free’ who grew up after the end of apartheid,” he wrote in an article on Cole for Tate Etc, “I can still connect and relate to his work and experience. We were both Black children growing up in the townships. Conditions may have since changed – but not enough.”

"Conditions may have since changed – but not enough."

-

This new edition of House of Bondage is as relevant today as it was in 1967. The structural injustices Cole highlights in his text and images still exist today. White supremacism still flourishes, rationalizations of where global populations can travel and work are still in effect around the world. “Why, why is it so?” asks Serote in his introduction to the book. “Why are so many people, children, youth, workers, men, women, nations subjected to such utter cruelty?”

The Aperture edition of House of Bondage is available in the Magnum shop.