The Day Havana Fell

On New Year's Eve 1958, Burt Glinn made a decision to leave a party and capture history as he bolted to Cuba to photograph the revolution

Over the course of New Year’s Eve on Dec. 31, 1958 and January 1, 1959, the reigning Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista, abdicated his position as a result of the growing revolution led by Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, who replaced the government with a revolutionary socialist state.

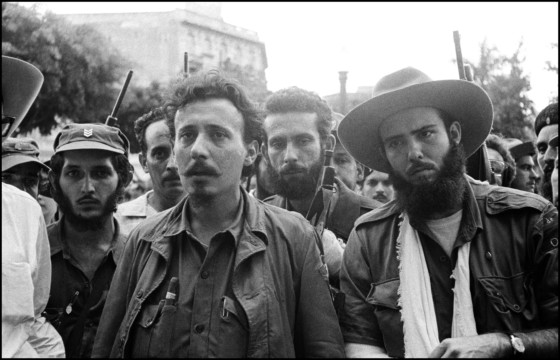

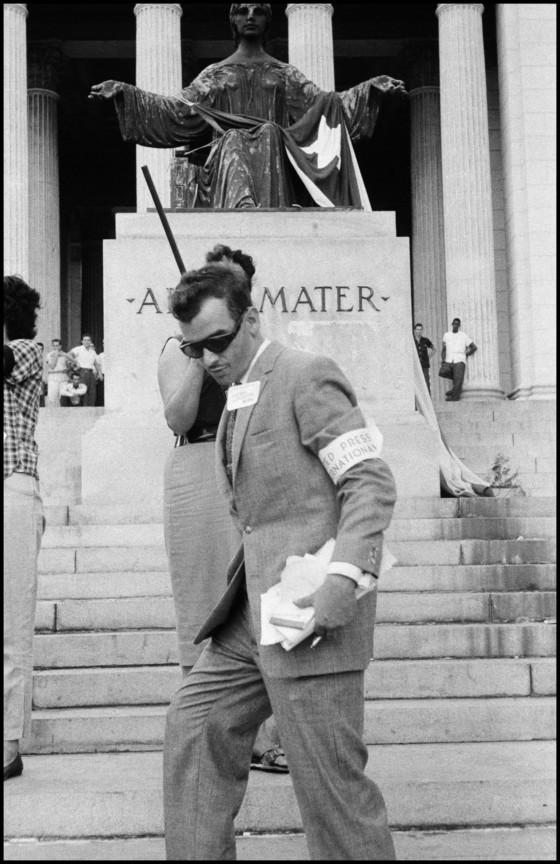

In the 2001 essay The Day Havana Fell, published in his book Havana: the Revolutionary Moment, Burt Glinn describes the combination of chutzpah and journalistic prescience that led him to leave a New York party and hop on a plane to Havana, arriving just after dawn on New Year’s Day, 1959. He went in search of a revolution, and what he found was one of the most revealing accounts of Fidel Castro and Cuba ever recorded. Glinn was able to grasp that, far more than bearing witness to some interesting news event, he had found himself in the very midst of history-in-the-making, at a moment of serious radical change. His images of Castro, thronged by his countrymen and women, as he stopped to encourage them along the road to Havana, of troops embracing, and of fierce men and women alike taking up arms in the streets, are full of the fervor, hope, and idealism that characterized very defining moment in Cuban history.

The last day of 1958 started promisingly enough. I was living in Manhattan, sharing an apartment with a friend who would turn out, to my surprise, to be legendary magazine editor Clay Felker. This arrangement afforded an excellent inside track on assignments from Esquire magazine and, since Clay was so much better connected, it did wonders for my social life, too. This New Year’s Eve, Clay’s network had gotten us, and two appropriately gorgeous young women, an invitation to a West Side party at Nick Pileggi’s. Nick was a reporter at The New York Times then, and when we arrived much of the talk was of the Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista. The word was that, at that moment, he had backed his trucks up to the treasury in Havana and was on his way into exile. Now I was, and am, a photographer with Magnum Photos.

"Under other circumstances, I would have had another drink and stayed at the party. But this time, pride was involved."

- Burt Glinn

Contrary to the romantic misconceptions about the job, I was not particularly brave. I really hated it when people I did not know began shooting at me. And I was not impetuous. I like travelling to the ends of the world taking pictures, but I like doing it on assignments when someone else has already agreed to cover my expenses and pay me a fee. This night everyone was on holiday and there was no time to get commitments. Under other circumstances, I would have had another drink and stayed at the party. But this time, pride was involved. Fidel Castro had been an outlaw and rebel in the Sierra Maestra for a couple of years. If you made the right connections and did not mind sleeping on the ground, he was reachable by the press . . .

Without a second thought, I was off. I borrowed whatever money I could from Clay, cabbed home, changed clothes – a tuxedo, even from Morty Sills, my politically radical tailor, is not appropriate for a revolution – packed my cameras and called Cornell Capa, who was then president of Magnum. Cornell knocked on every door in his building and raised whatever cash he could for me. I arrived at LaGuardia Airport in time to make the last Yellow Bird to Miami, with my gear, an Air Travel Card, $400 in cash, and no idea what I was doing.

In those days there was a first-come, first-serve charter shuttle between Miami and Havana. But at 3a.m. on New Year’s morning, the Miami airport was deserted. There was no one at the other charter counter but there was a phone with a line to the pilot. After a lot of expletives from him about the hour, I explained that there was a revolution going on in Cuba and that I had to get there as soon as possible. He assured me that no matter what hotshot TV journalist came or how much money he was offered, I would have the first seat to Havana at daybreak. And for all of twenty dollars I did.

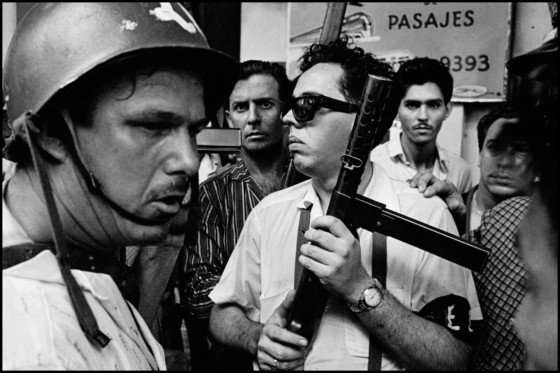

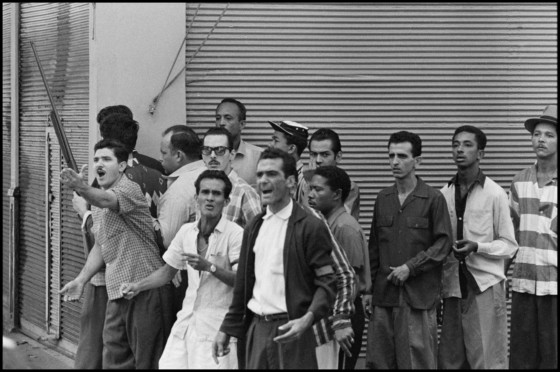

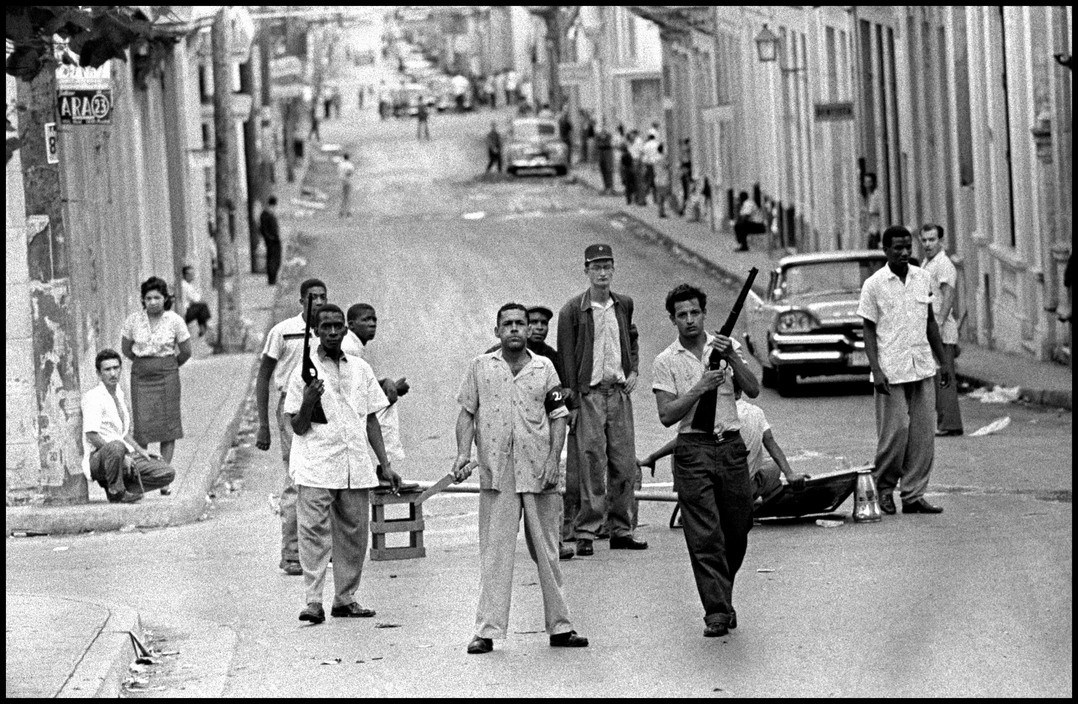

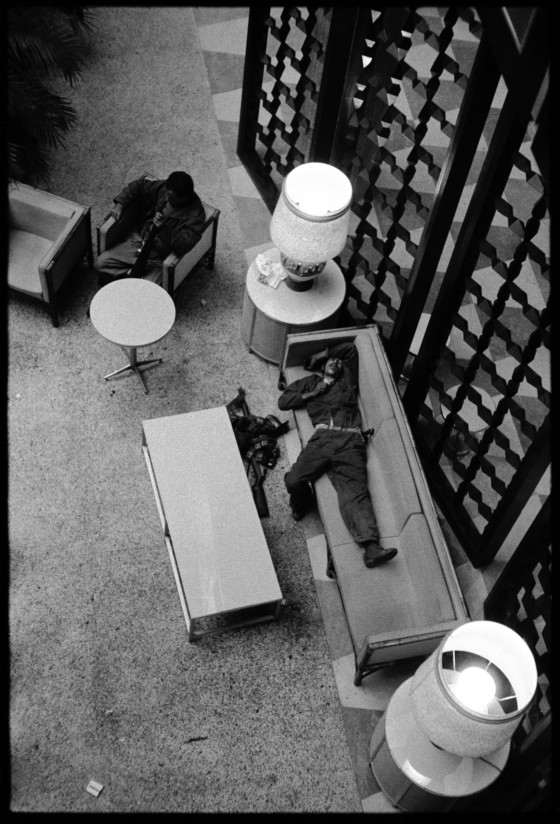

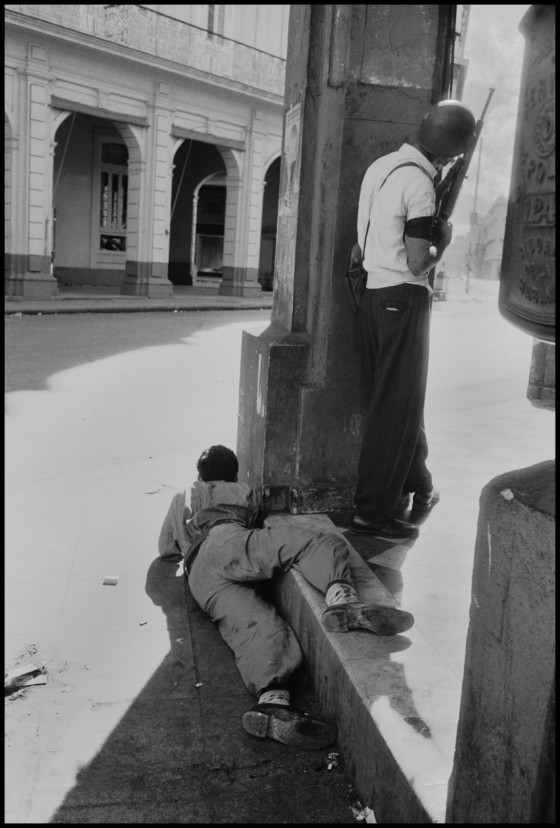

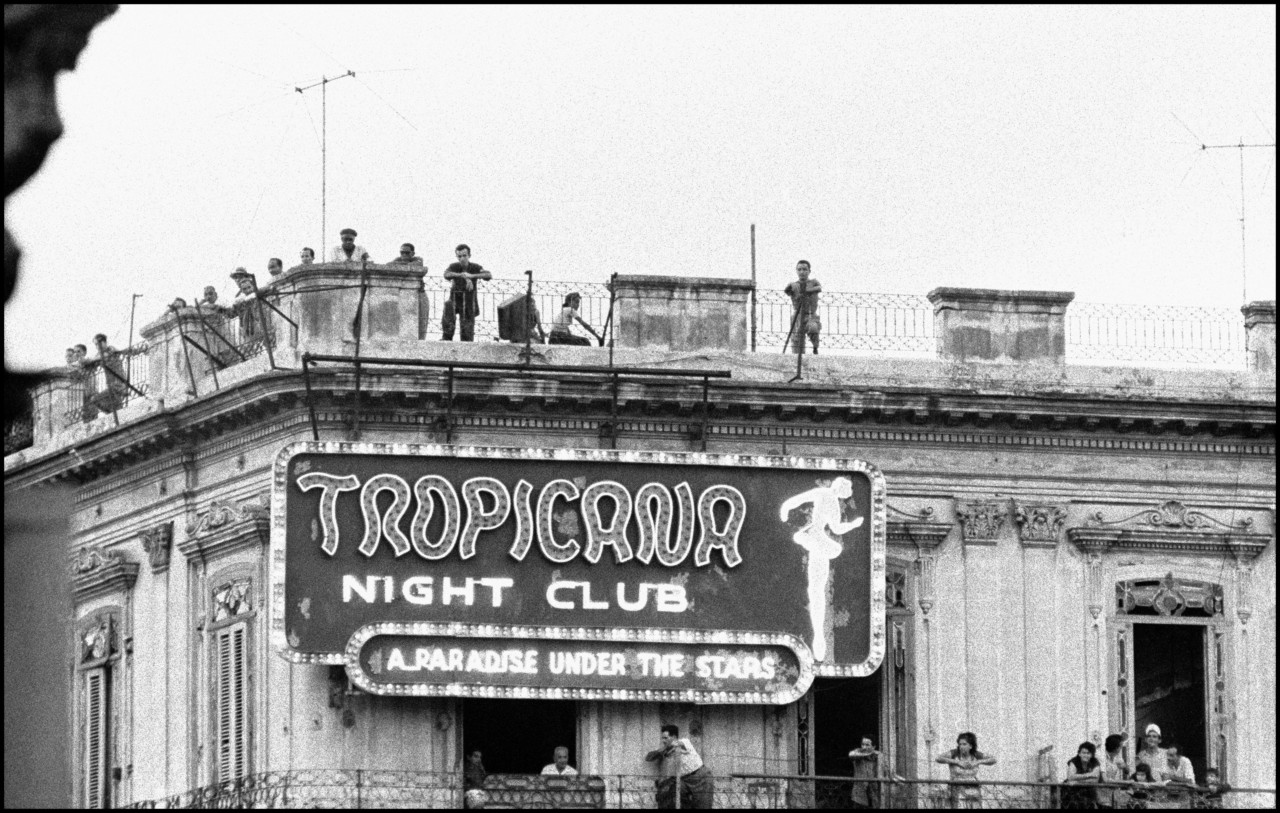

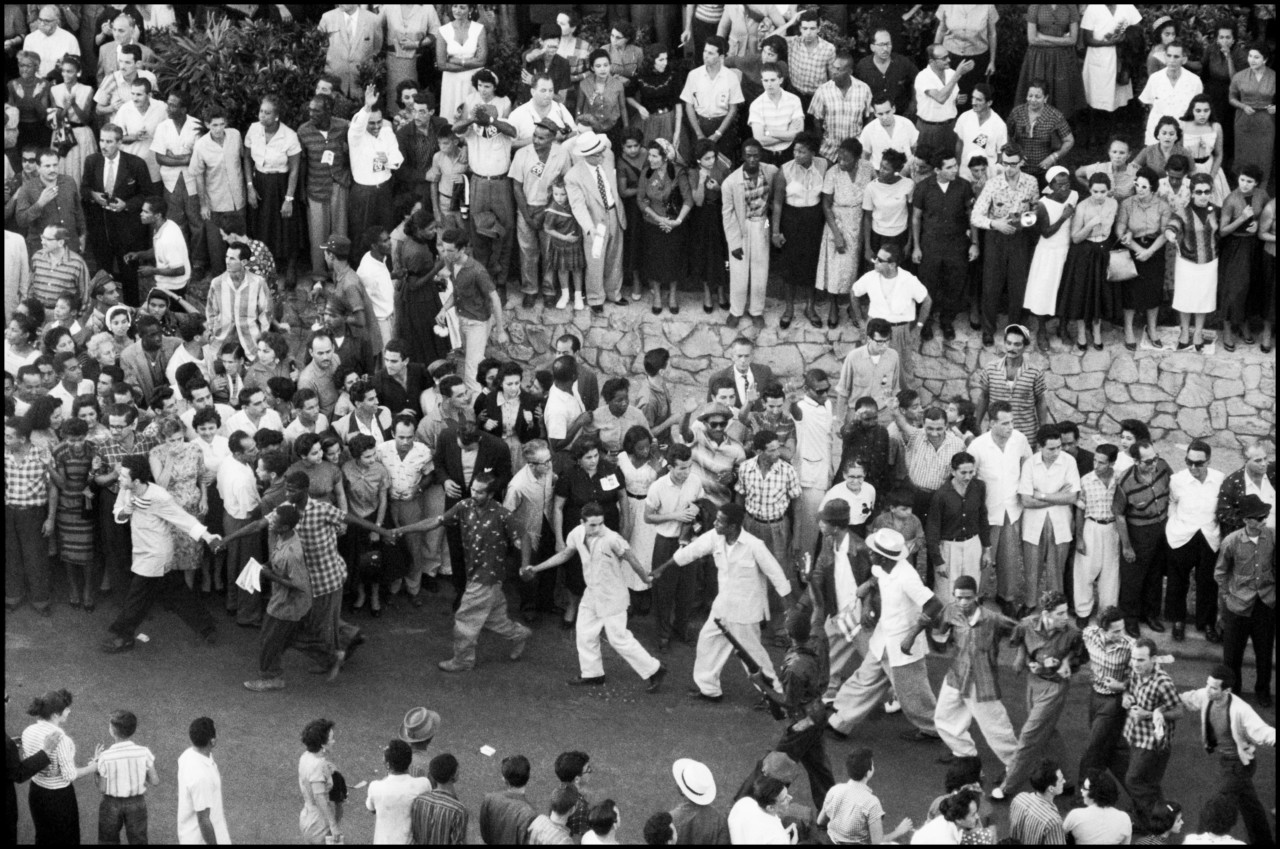

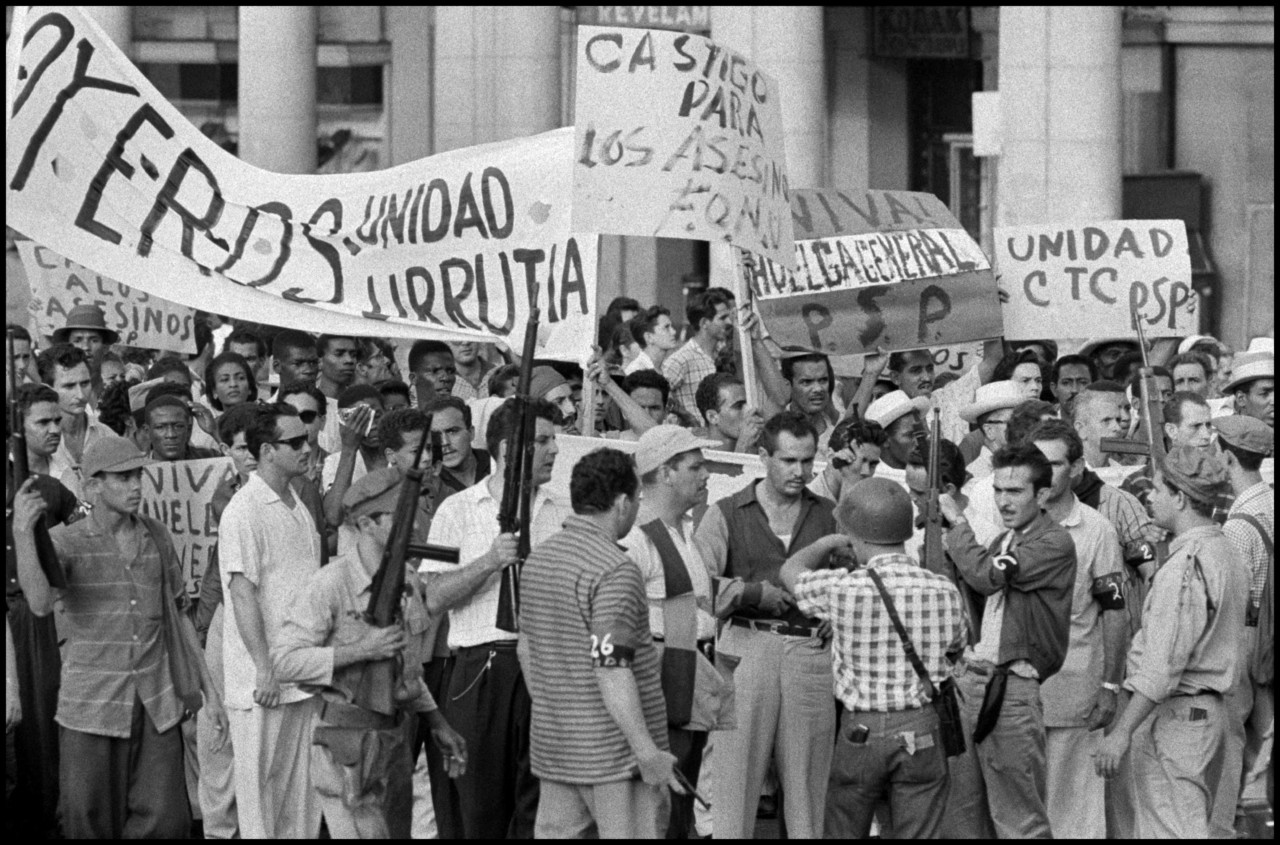

By the time I arrived, it was past dawn in Havana. Batista had fled. Fidel was still hundreds of miles away, although nobody knew exactly where. Che Guevara was on his way to Havana and nobody seemed to be in charge. You just can’t hail a taxi and ask the cabbie to take you to the revolution. Without any sleep, I checked into the Sevilla Biltmore in downtown Havana, which figured to be near the action, and I looked forward to a shower, a nap, and a quiet period cleaning the cameras and girding my loins. Not bloody likely. The moment I got to the room there was gunfire in the streets. It’s not my favourite sound, but from the hotel window I spotted a couple of photographers running towards the firing. Cursing their industry, I grabbed my stuff and made for the street. Leaderless crowds were gathering, armed with whatever they had at hand: pistols, shot-guns, machetes – whatever. They raided the casino in the plaza hotel and some other office buildings where they suspected Batista sympathizers.

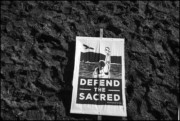

There did not seem to be much opposition, but there was a lot of firing. You could not tell who was shooting at whom. People appeared in the streets wearing “26 de Julio” (the name of Fidel’s movement) armbands and helmets with “26” painted on them. On the first day, it was not clear who was a legitimate rebel and who was a summer patriot. I spent most of my time trying to figure out what was happening and mooching as much information as I could from the other journalists who were old Cuban hands.

" Leaderless crowds were gathering, armed with whatever they had at hand: pistols, shot-guns, machetes – whatever."

- Burt Glinn

The remnants of the government Batista left behind had named a provisional president, but it was obvious that this quickly patched-together arrangement would not work. From Santiago, where the rebels had taken control, Castro called a general strike to show the old guard who was really in charge. This may have been great for the Revolution, but it was bad news for the journalists. For the next five days, all the stores and restaurants were closed. So were the bars and groceries and liquor stores. Fortunately in Havana, no matter what, you can always find a cigar and a bottle of rum. That is primarily was kept us going.

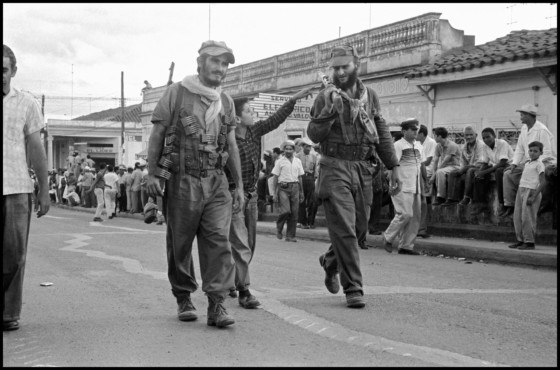

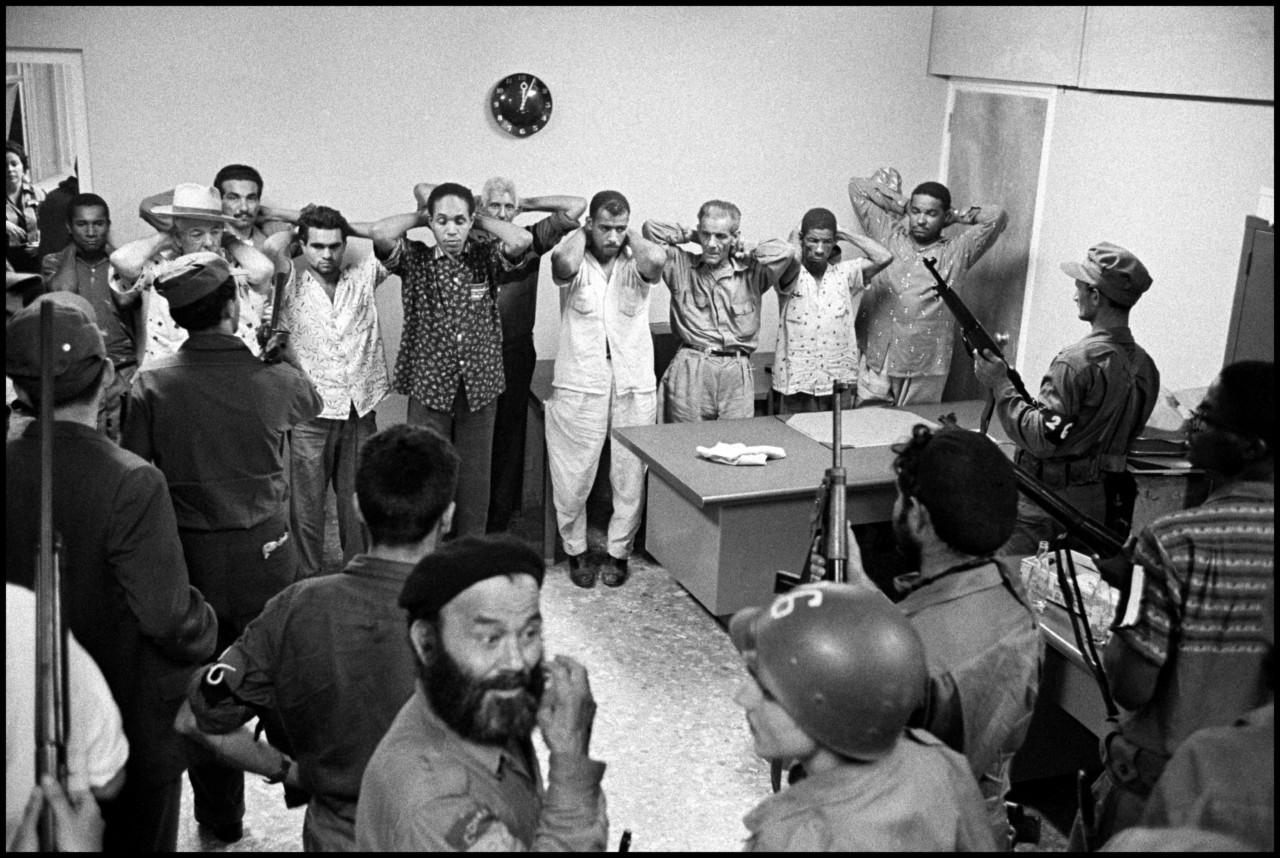

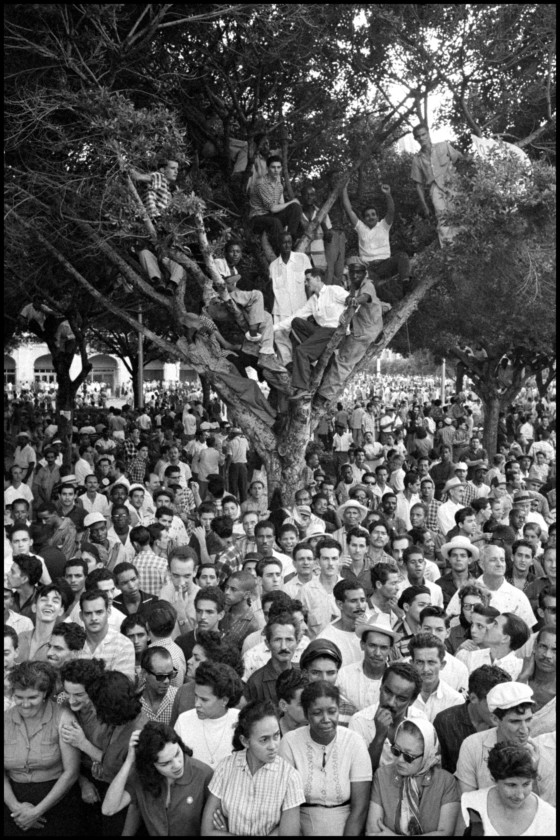

By the second day, hungry, sleepless, and still confused, I found the police station where the rebels had rounded up Batista’s secret police, at least the ones they could find. I photographed all of those newly terrified captives, classic cases of shoes on the other foot. By this time Che had arrived in Havana but was unavailable to us. Rebel general Camilo Cienfuegos was on his way, and the real barbudos, or bearded ones, had begun to come in from the hills. Castro sympathizers emerged from hiding and ecstatic reunions between mothers and sons and old friends were seen everywhere. The abrazo (embrace) was the gesture of the day. Crowds gathered and celebrated.

Everyone was calling for Fidel, but nobody knew where Fidel was. There was no press office; this was not a photo-op, it was a real revolution. The reality of where I was and what I was doing sunk in. I was exhilarated. I was in one of the great adventures in my life.

In the meantime, the Life magazine team – writers Jay Mallin and Jerry Hannifin and photographer Grey Villet – had organized their own transport and teamed with a Venezuelan photographer. At this distance, no one can remember his name, but everyone called him Caracas. I think he must have been a good photographer, but I know he was a hell of a quartermaster. He could always find something to eat . . . He kept us in enough chicken sandwiches to survive and enough rum and cigars to prevail. And it was Caracas who finally spotted Fidel on the road between Camagüey and Santa Clara.

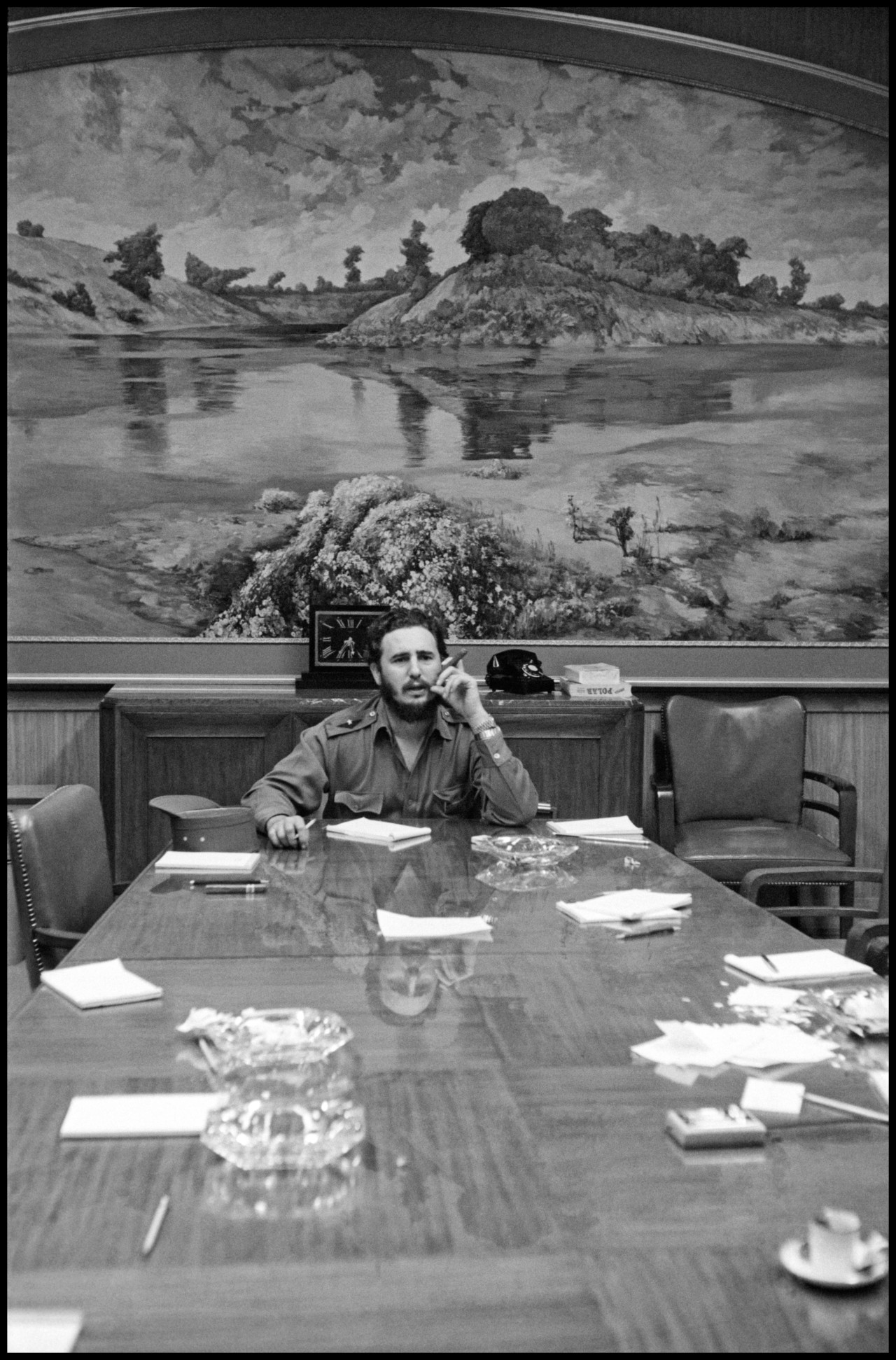

After an all-night speech in Sancti Spíritus, the Castro group had dwindled momentarily to four cars, carrying Fidel, his aide Celia Sánchez, and an escort of about eleven bearded ones. We had made contact with Fidel but it was hard to keep track of him. He had started in the Sierra Maestra without any official vehicles but as he progressed from Santiago, Camagüey, Santa Clara and Cienfuegos toward Havana, the column grew. Somehow the rebel entourage acquired tanks, trucks, buses, jeeps, cars, taxis, limousines, motorcycles and bikes.

Castro kept changing vehicles and we kept playing tag with him all the way, trying to spot him in the column on the road. As the caravan traversed the countryside, it would roar through towns where people lined the streets, cheering.

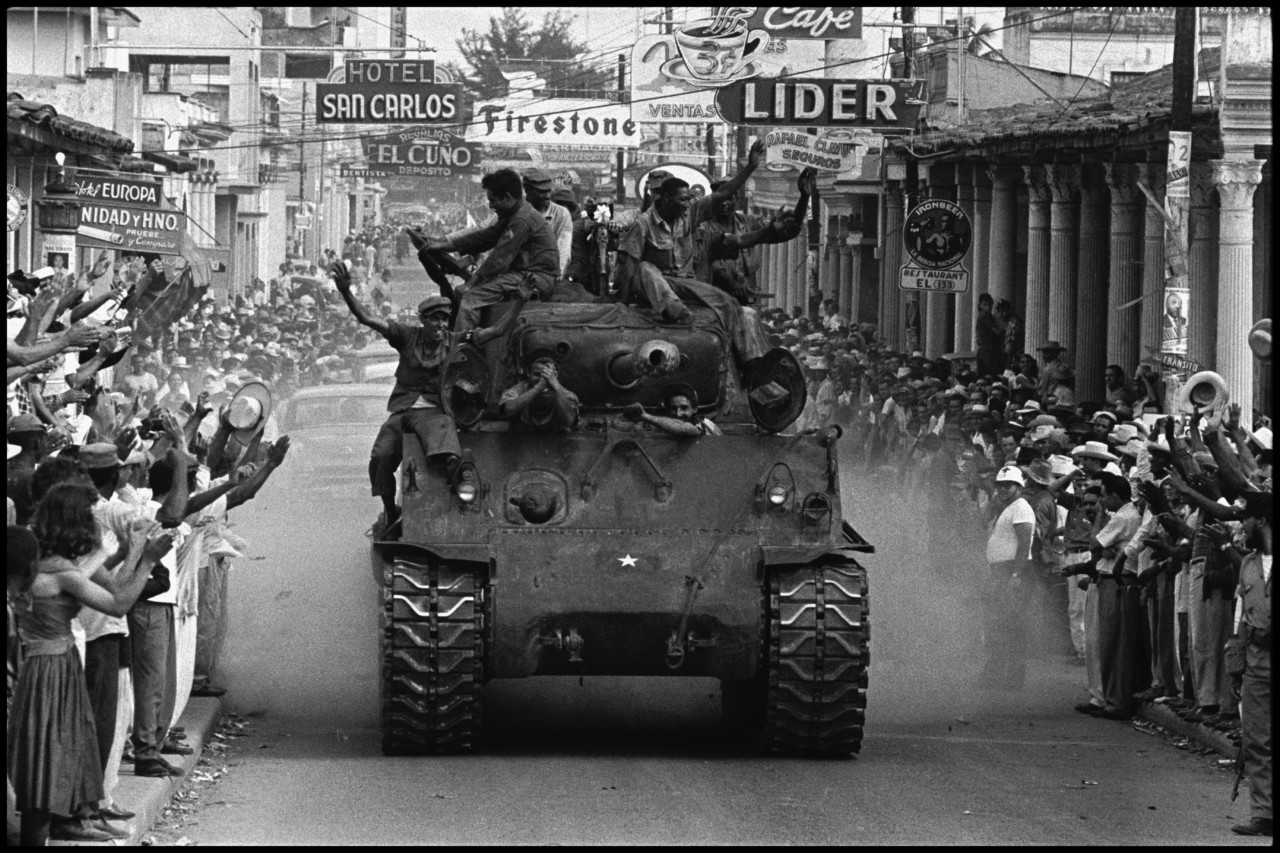

At Santa Clara, about 180 miles from Havana, the momentum really grew. The column arrived in a disorganized frenzy. Nobody knew which car Castro was in but they were delirious. Santa Clara had been the site of the one big battle of the Revolution, and when Che Guevara took the city it was a signal to the army that it was finished, and Batista fled. Although the city was already in rebel hands, Castro’s arrival was greeted like the liberation of Paris.

In Cienfuegos he started speaking at 11p.m and went on until two in the morning. He involved his listeners, asking them for advice on how to run the country. He climbed down from the platform into the crowd and discussed farming methods with them and exchanged jokes about the deposed Batista. It was an incredible demonstration of two-way faith. Considering the situation, his entourage was worried about an attempt on his life, but Castro was fearless. Fidel spouted no Marxist jargon in those days.

He made contact with the people all along the route form the mountains to Havana. Sometimes he would stop to buy gas for the column. He would sip a beer or a coke and ask the attendants for directions along the road. He talked with nuns, with middle-class matrons, with children. None of the conversations were political. The euphoria was incredible and permeated the whole country.

How sad to think of what has become of that moment. Che may have been right, but I wonder what would have happened if we had made an all-out effort with Fidel. Certainly anyone on this mystical magic tour to Havana would have known better than to believe the exiles’ theories about Castro’s unpopularity that two years later became the foundation for the US-financed invasion now known as the Bay of Pigs.

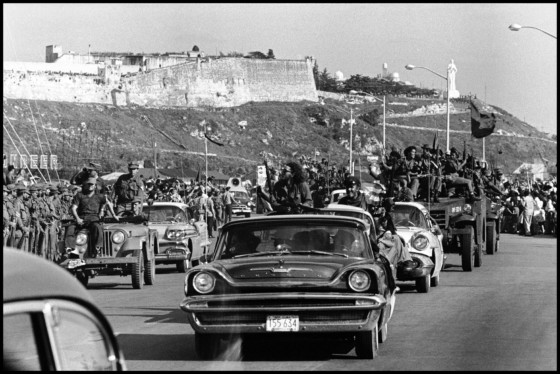

After leaving Cienfuegos, the route became so unruly that we lost Fidel until we caught up with him on the entry to Havana. By now the crowds were so tumultuous and the ranks of the marchers so swollen that it was impossible to differentiate the procession from the audience. Arriving in Havana, the crush along the seaside Malecón was so great that I lost my shoes while struggling to get my pictures.

We neither slept nor ate regularly nor bathed on the nine-day trip to Havana. But those were great days. I did learn then that a good cigar can be life sustaining. But I also remember the wild hopes and the ominous portents that filled those brief days. I only wished in all these years since then that Fidel had done the Cuban people better and that we had been smarter.

I think I would trade all of these, my favorite pictures, and all of the great cigars I have had from Cuba, if we could do it all over again. Only better this time.