Generation X

The story behind one of Magnum’s first collective projects investigating the postwar generation and why it’s inspiring the agency’s latest endeavor

Over 70 years ago, Magnum embarked on an ambitious project led by Robert Capa — their second large-scale collective storytelling feature, this time exclusively under Magnum’s coordination. They sought to understand the young generation at the mid-century threshold: Generation X. Today, nine Magnum photographers profile Generation Z, using this historical project from the archives as inspiration. Their photographs and interviews will be published in this year’s edition of Magnum Chronicles.

Explore Magnum Chronicles here.

“It suddenly struck me that something called the half-century was impending,” thought Robert Capa in 1949.

“At Magnum, most of us were close to our forties, which is just about the halfway mark in the life span of a human being. So we congratulated each other on our exceptional luck in being able to spend our lives in two so different halves of this great century. We talked about expectations we had when we were 20, and we found out that although the members of Magnum came from different countries, our hopes as 20-year-olds were similar — but very different from what has happened since then.”

This retrospection gave Capa an idea that would allow members of the newly founded Magnum Photos to travel around the world, establish the agency on a global scale, and touch upon a question of international concern: who was the new generation coming of age in the shadow of World War II, facing the onset of the second half of the century, and hoping to live until the year 2000?

“Bob was the ideas man, the promoter and the salesman,” said Magnum co-founder, George Rodger. “Project after project poured from Bob’s fertile mind, and our tiny office in the Faubourg Saint Honoré was where his ideas were sifted by the rest of us.” As was custom, Capa eagerly began to devise a plan.

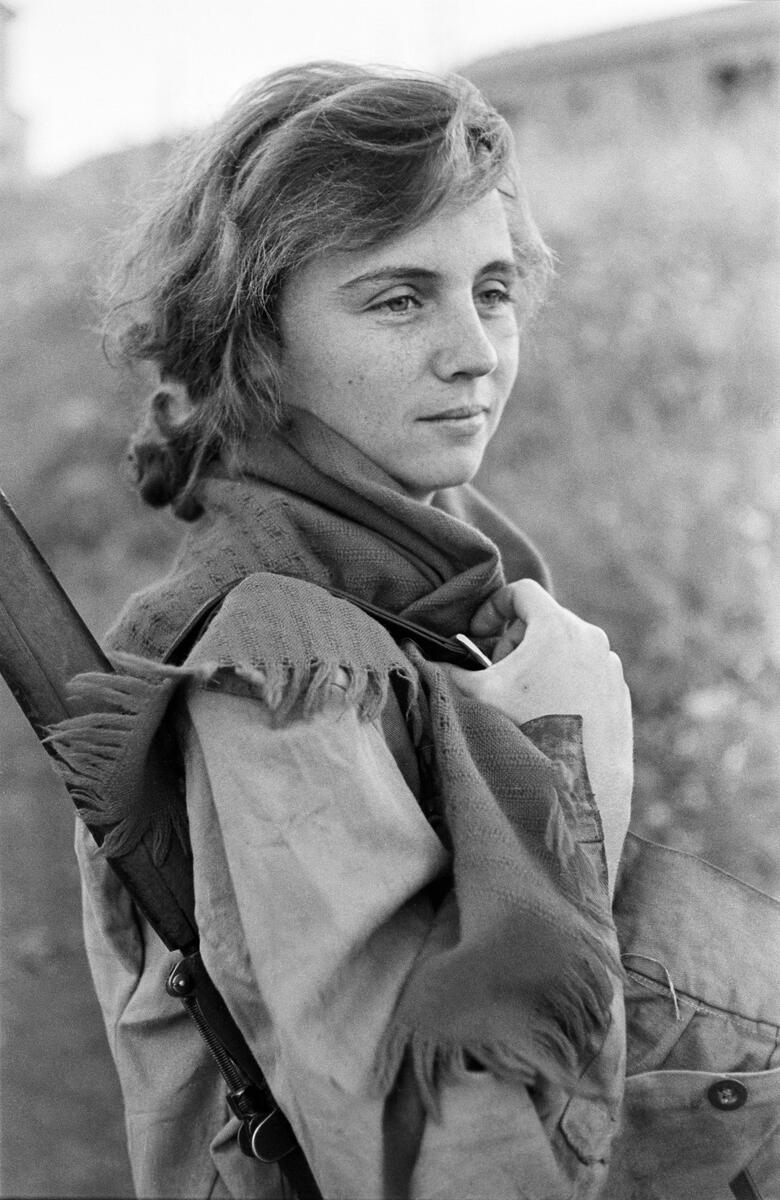

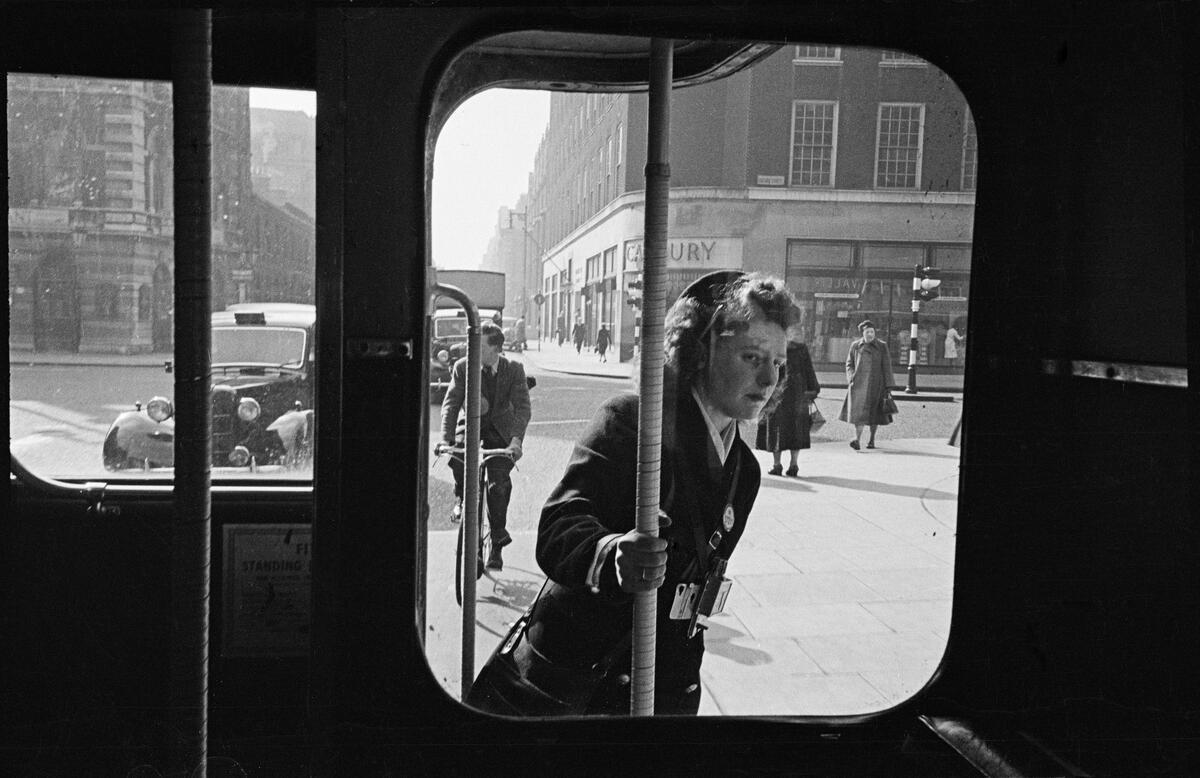

Grounded in the cooperative’s humanist vision, Magnum members and Capa’s recruits scattered across 14 countries and five continents. For three years, they turned their lenses towards the everyday experiences of young men and women around the world, portraying “their present way of life, their past history, and their hopes for the future,” said Capa.

Oriented towards shared human values and faith in a unified society, the project became an antidote to the Cold War threats of nuclear decimation and the lingering trauma of World War II as the world stitched itself back together.

"We named this unknown generation the Generation X."

- Robert Capa

The generation would be seen as individuals inspired by desires and ideas, not mere numbers. The project would “introduce viewers to human beings, which are easier to relate to than statistics or even text-only presentation of the subjects and their data,” says Matt Murphy, Global Director of Archive and Digital Production at Magnum. “The focus is on a fresh generation who had witnessed WWII, and who would be responsible for leading the world into the new postwar era,” Murphy adds.

They named this “unknown generation,” in Capa’s words, Generation X.

Generation X

In 1948, a year before this ambitious project first germinated, Magnum photographers participated in the project “People Are People the World Over,” spearheaded by Capa and editor John Morris, and published in Ladies Home Journal, profiling the daily lives of 12 families around the world.

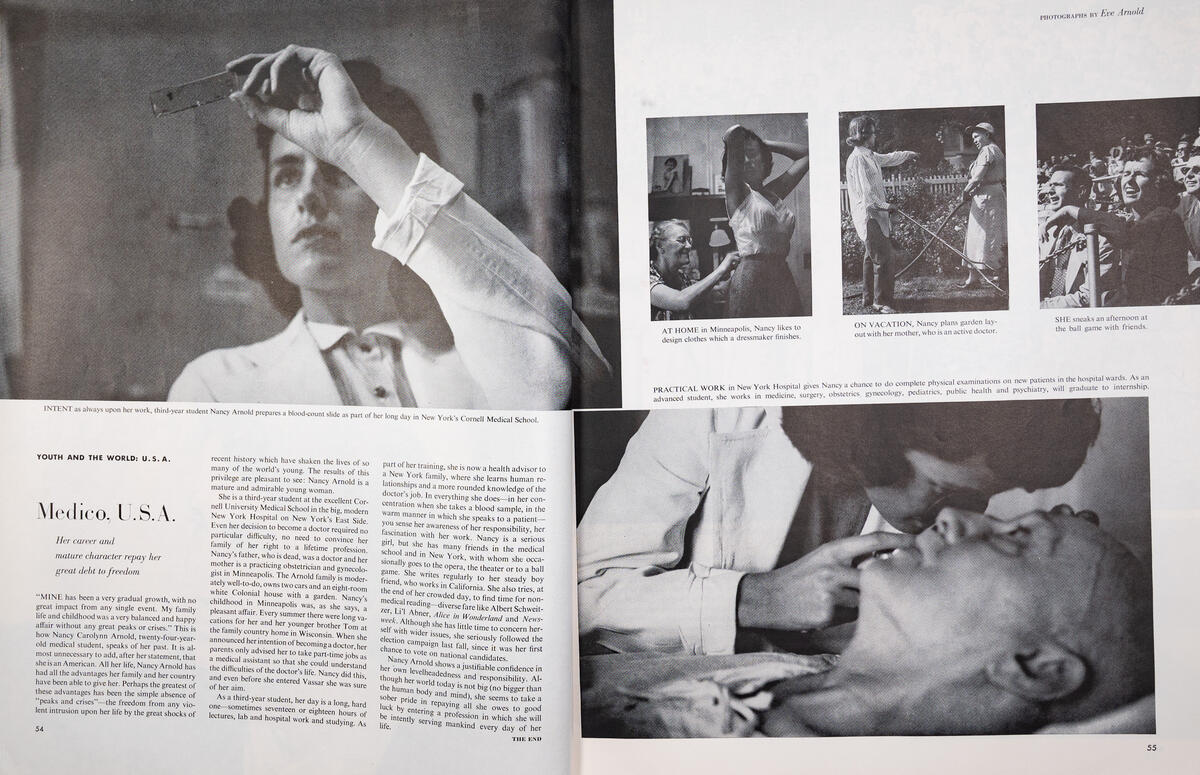

Capa was determined that this time the project be exclusively for Magnum members and collaborators. Energized from the success of “People are People,” he pitched his idea to the magazine McCall’s, who agreed to provide a substantial advance. Yet, due to the project’s scale, the photographer would need more recruits. Soon, a total of 11 photographers would sign their names to the story, seven of whom remained Magnum members: Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger, David Seymour, Eve Arnold, Werner Bischof and Herbert List.

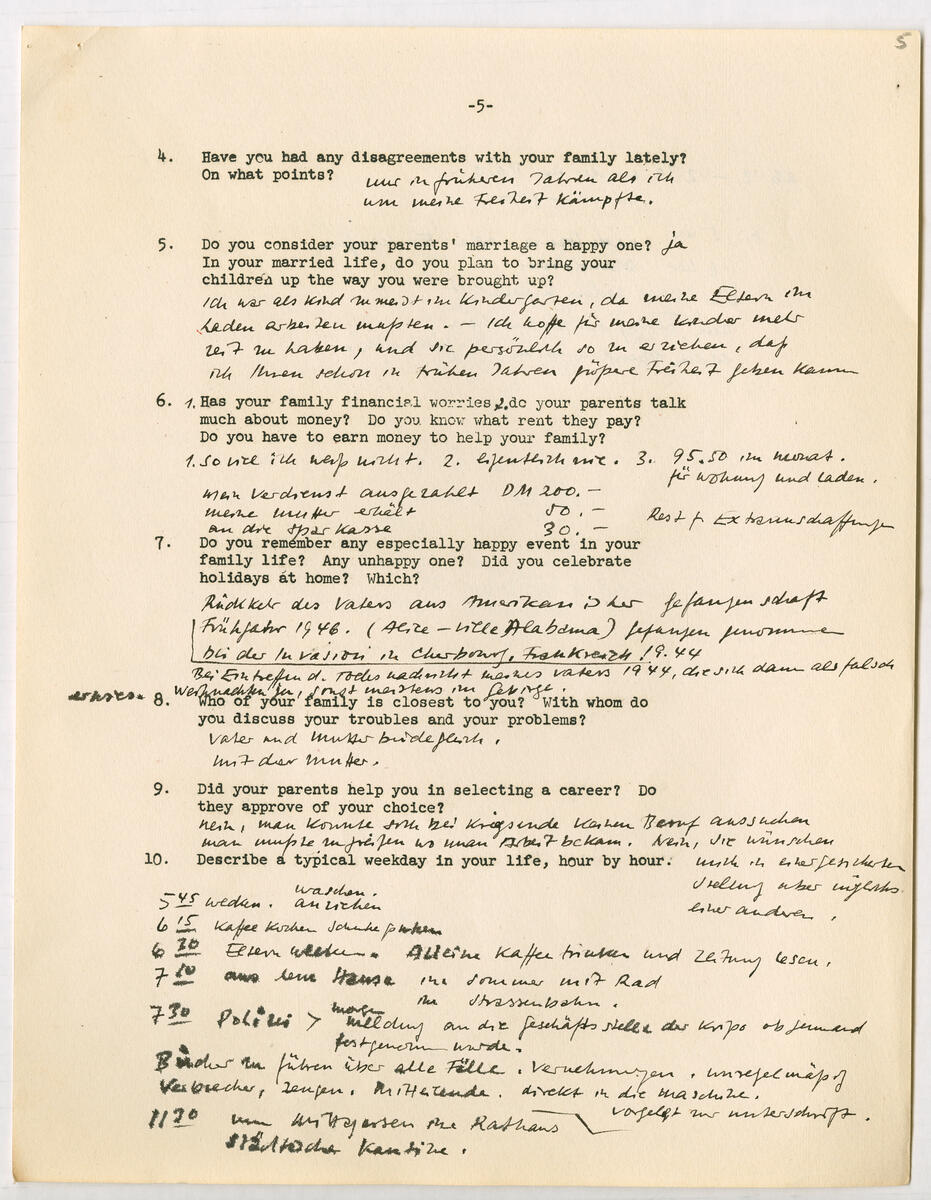

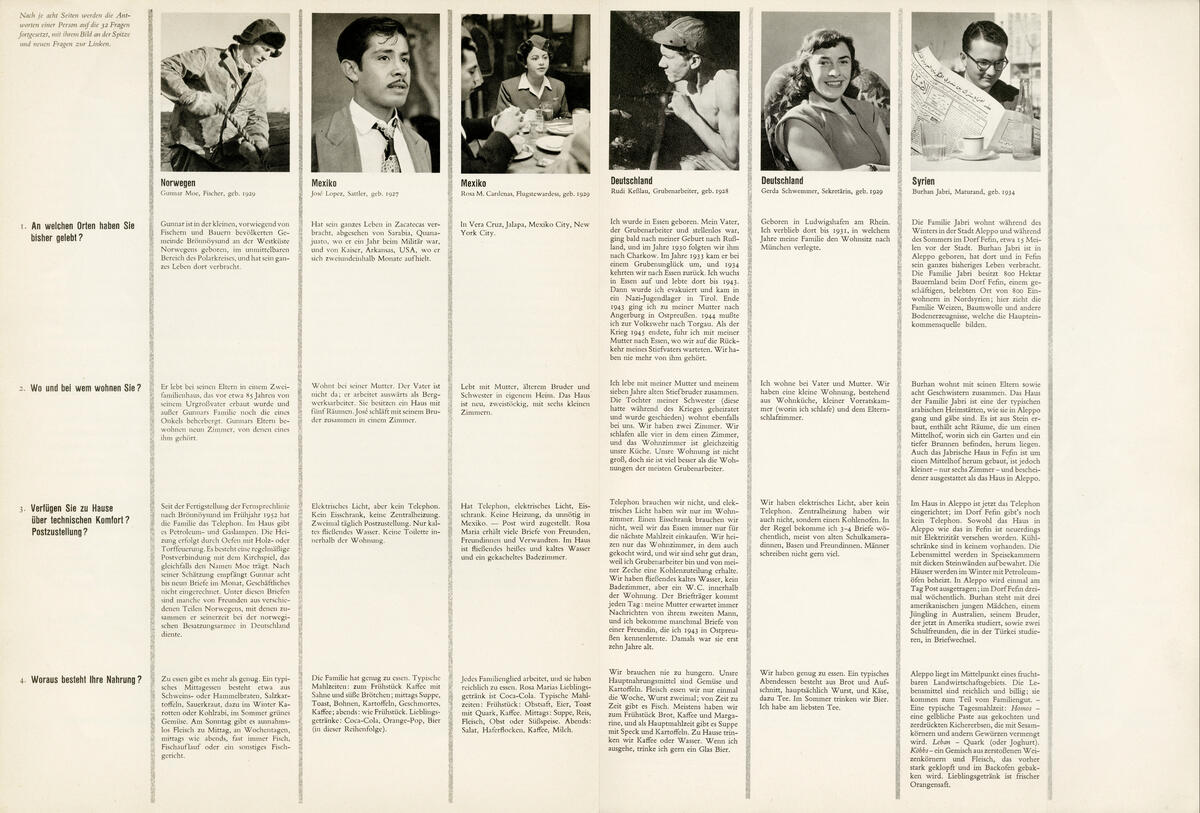

To get to the core of the hopes, fears, and daily lives of the 20-25 year olds, the photographers created a questionnaire for their subjects. What do you do on the weekends? Were there any national, local, political or personal events that influenced your childhood? What do you think of the United Nations? Do you have a telephone at home? How many children do you want to have?

"Project after project poured from Bob’s fertile mind, and our tiny office in the Faubourg Saint Honoré was where his ideas were sifted by the rest of us."

- George Rodger

The subjects were as distinct in cultural heritage and personal history as they were in their position in society. Ubaldo Orsini, photographed by David Seymour, is an impoverished 21-year-old farmer and musicophile from Gubbio, Italy, who reads romantic love stories. He vividly recalls the moment Nazis murdered 40 hostages from his village. Working nearby that day, he heard their cries to their patron saint, Ubaldo, his namesake.

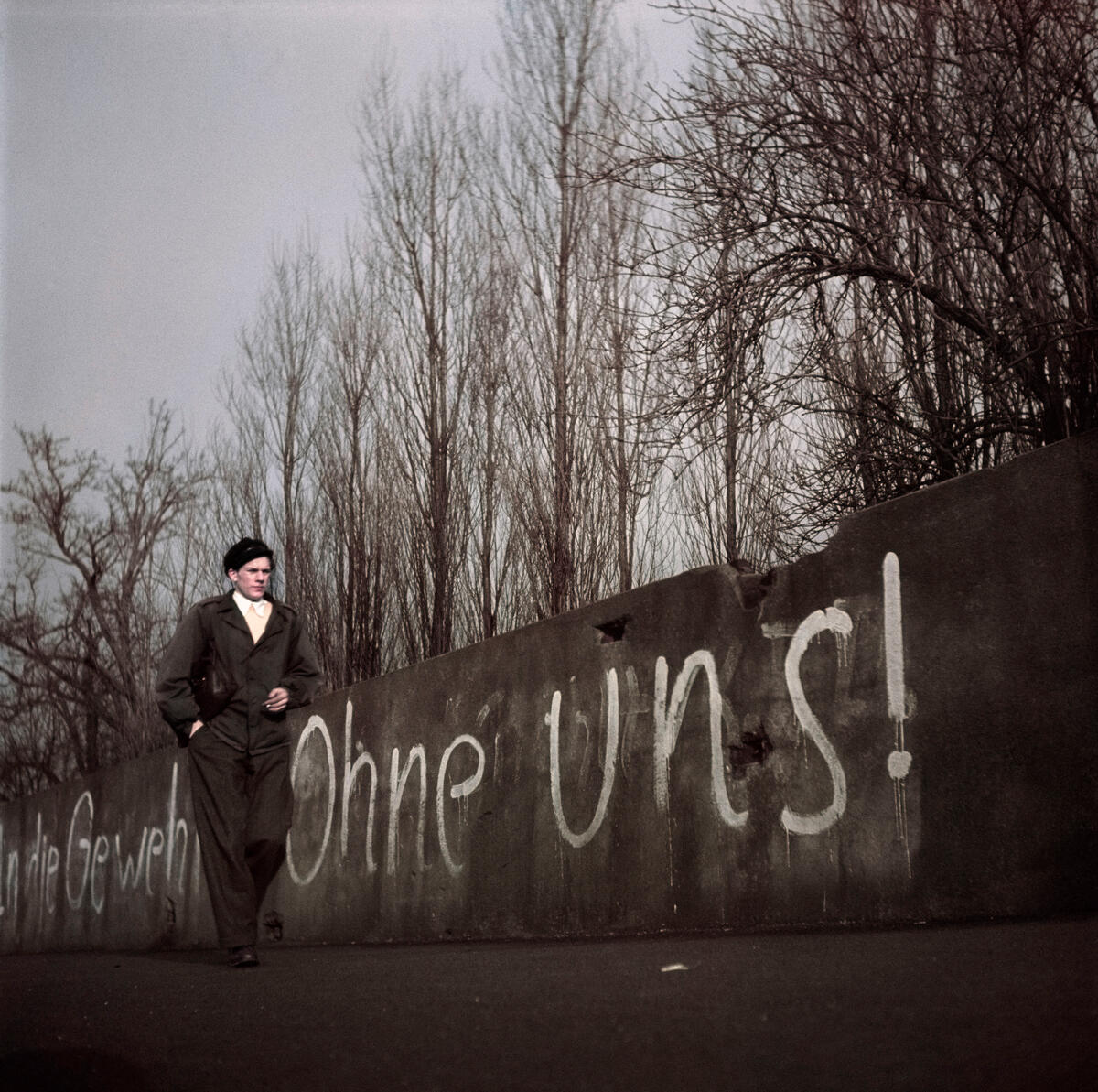

A young mother, Carmel Abramson, who lived in a Kibbutz in Israel, was photographed by David Seymour. “We are trying to create something out of nothing,” she says. “That is the spirit that moves us here.” Rudolf Kesslau, a former Nazi youth, is a sullen coal miner in Essen, the only financial supporter of his family, photographed by Robert Capa.

Werner Bischof, who had traveled to Japan after covering the Korean War, was mesmerized by the country and stayed for almost a year. He photographed Goro Suma, a poor 24-year-old law student in Kyoto and partisan of the Communist cause, who made $20 a month as a secretary in the school labor union, and 20-year-old Michiko Jinuma, a fashion student.

Women who were becoming more empowered to make their own choices and resist confinement to the domestic sphere also feature in the series. Despite traditions of female subservience, Bischof writes, Michiko “demands the same rights as men. She goes to the theater, to the movies, sits in cafés, goes shopping. In short, she has become modern.”

Capa’s profile of the young German and Bischof’s portrait of Suma offer “insight into the defeated nations of World War II and addressed latent fears among American leaders and the public. Have young Germans learned from their country’s mistakes? Would the Communist wave take hold of Japan?” writes Nadya Bair in The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market.

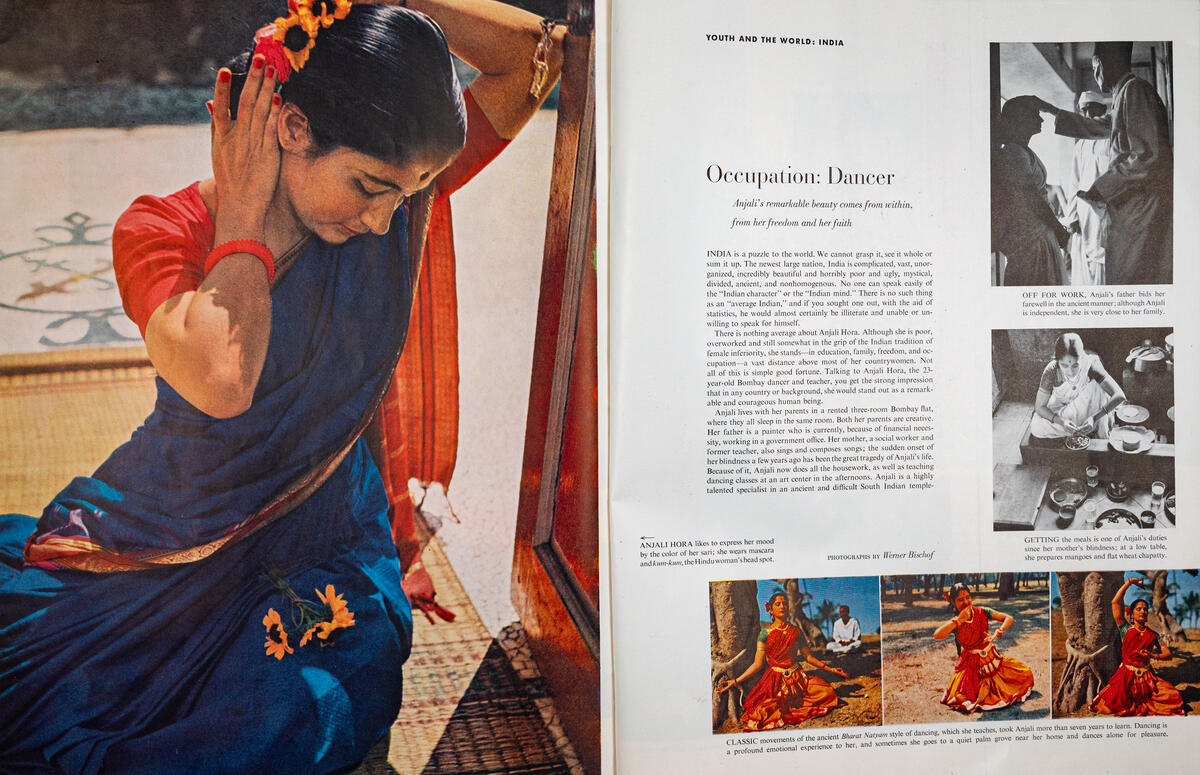

Bischof also met Anjali Hora, a bright 23-year-old Indian dancer of the Bharatanatyam tradition, compelled towards her craft despite living in poverty. “Indian dancing is steeped in history, religion, and music. […] With our cultural renaissance coming along in Indian life, I feel there is a great future in it,” says Hora.

Under her married name, Anjali Mehr, she became a celebrated dancer, choreographer and scholar, and was the Head of the Department of Dance at Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda. While she died in 1978 at the age of 50, never seeing the millennium as Capa had once imagined, a memorial organization bears her name.

Publication

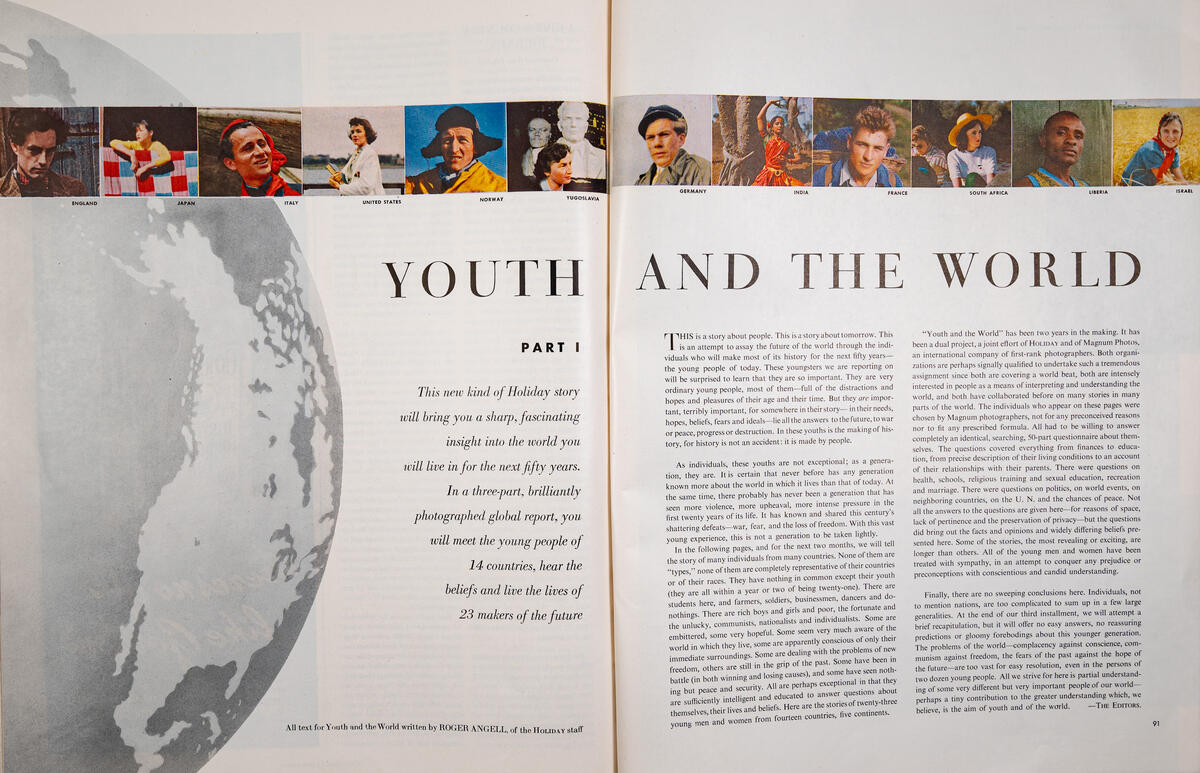

The Generation X project was published in 14 publications throughout the world, including Point de vue, Images du monde in France as “Jeunesse du Monde” in December 1952; Holiday in America as the three-part serial “Youth and the World” in January 1953; and Du in Switzerland as “Generation X” in January 1954.

“Because we know astonishingly little about those born around 1925 (there is far too little written about them, too little attention), they were named ‘Generation X,’” reads the introduction to the series in Du. The latter publication became an etymological landmark; it was the first time Generation X is used to describe this demographic.

“Youth in the World” not only earned more work with Holiday for the agency, it also shaped the magazine’s editorial approach to include more serialized stories.

Yet despite the project’s success, it was not without trepidation. Capa was hesitant of Holiday’s editorial angle as the series materialized: the magazine’s choice to compartmentalize countries risked politicizing and polarizing them, which was not Magnum’s intention. Capa was concerned that this country-by-country format pigeonholed cultures rather than revealed a common ground.

“I am more and more convinced that we should mix not only the persons, but the countries, to show more contrast and to show how many different continents and backgrounds can produce the same type of thinking in the same generation,” Capa wrote to Holiday’s photo editor, Louis Mercier, in 1952.

“Capa wanted the series to focus more on the people as individuals rather than allowing them to stand in for larger American political and economic concerns. He also wanted more emphasis on the young people’s forecasts for the future and their everyday lives, which would allow readers to see their commonalities despite cultural and geographic differences,” wrote Bair.

Capa’s sentiment shows the agency’s distinct vision and desire for control over their earliest group editorial projects. In the end, Holiday’s conclusion did glean commonalities within Generation X, noting that they showed no bitterness or despair. Denouncing violence, they wanted a “break from the past,” a sense of security, and respect for individuality.

Du had a more lateral conception, listing the interview answers side by side, also touching on the generation’s kinship. “Does something common emerge?” the introduction to the series asks. While the generation might be “thinking of a Third World War, […] they are not world-weary or filled with hatred. Most strive toward the normalities of an orderly life, even when they adopt — more easily than other generations — unconventional habits.”

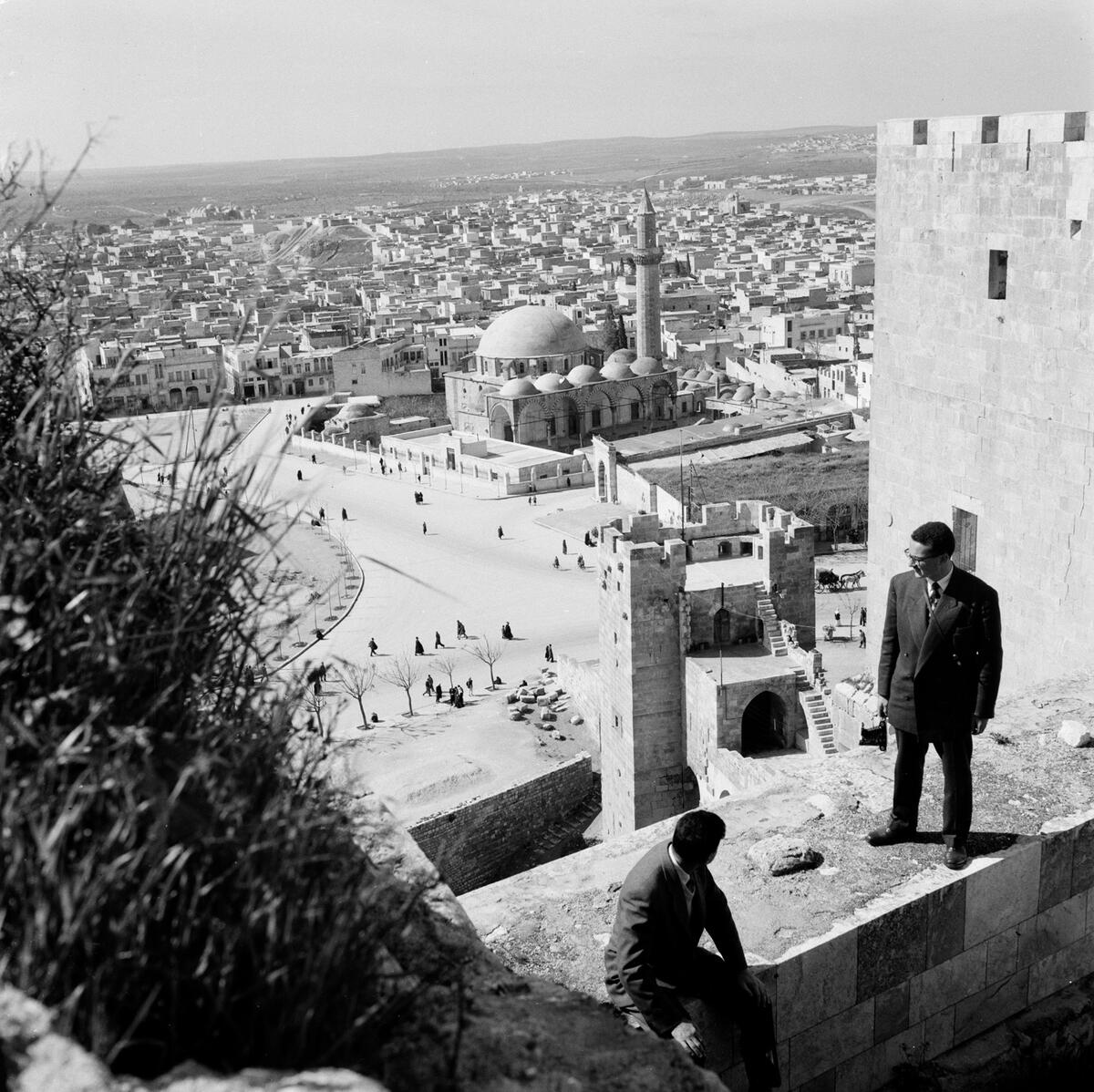

Many of the subjects’ answers, however, suggest a shirking away from the political arena. Sylvia Andrews, interviewed by Capa in England, said she “is not interested in politics, international affairs, or the United Nations,” while Syrian engineering student Burhan Jarobi said he has “turned his back on politics.” “No politics for me,” said Rudolf. “I may have believed some of things the Nazis taught us, but no politics — nothing good will come out of that.”

It is as if, on the precipice of a new era, they attempted to dislodge themselves from the burdensome aftermath of the war, to reinvent themselves as the world was being reconstructed around them. The label Generation X thus became an unanswered question for what they were to become.

“Youth in the World,” which won an award from the University of Missouri School of Journalism, was a turning point for the cooperative. It proved the agency could effectively produce their own complicated editorial projects on a global scale, involving multiple photographers with distinct aesthetic signatures.

Werner Bischof’s image of famine in Bihar province, India taken while he worked on the project would be displayed in Edward Steichen’s momentous traveling exhibition The Family of Man, which premiered at the MoMA in New York City in 1955.

Generation X was not only about trying to understand a generation, it was made for them. It was a send off for their future as they faced the rest of their lives. The final words in the introduction to “Generation X” in Du magazine are: “The future demands people of both open and strong character. May Generation X grow through its challenges until each individual lives as a rich, expansive whole, connected to the universal wholeness of the world.”

Capa would live to see Generation X published in the January 1954 issue of Du. He died only four months later.

Magnum Chronicles: GenZ

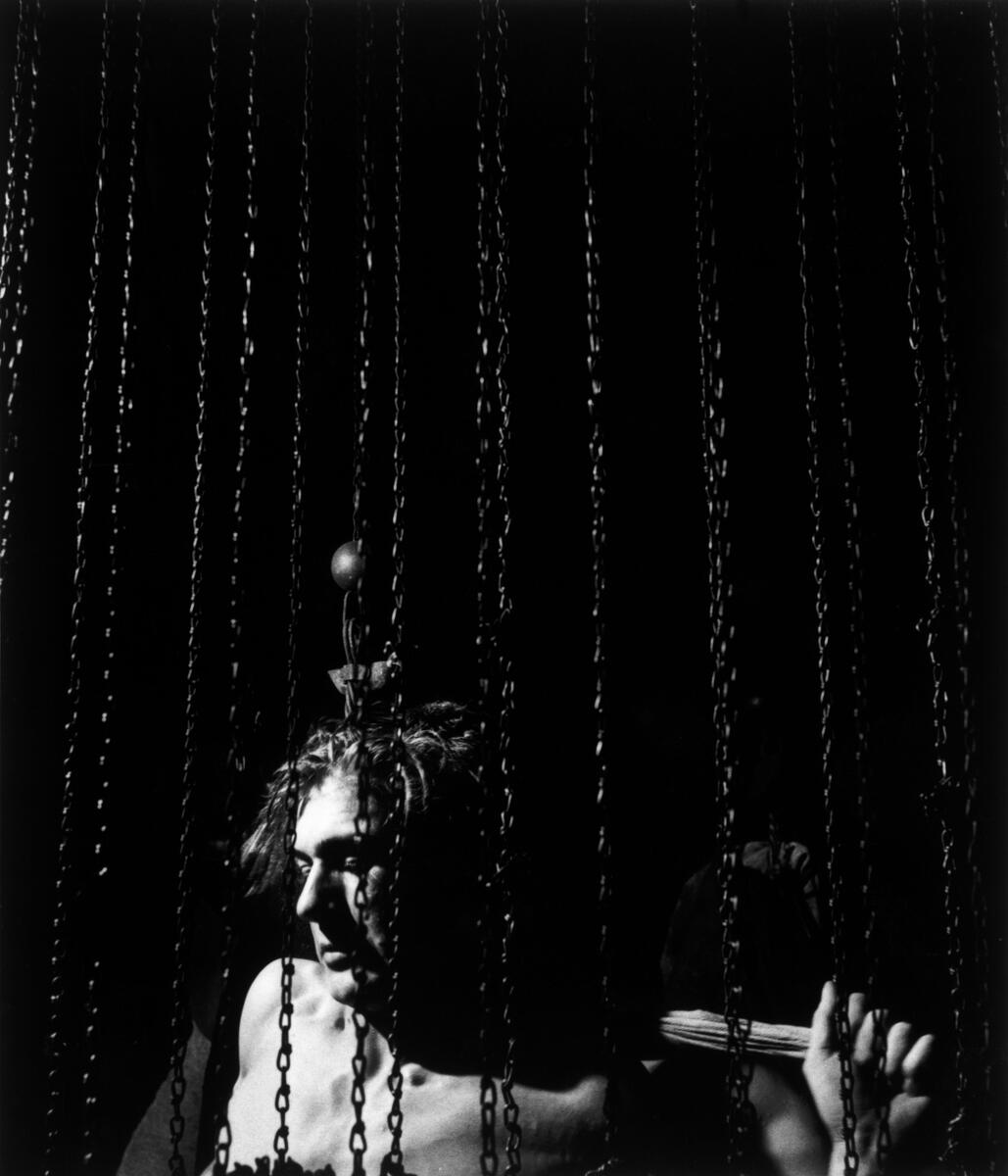

More than 70 years after Magnum’s global, collective storytelling endeavor, the agency revisits this archival project for a new initiative. Magnum Chronicles, an annual publication by Magnum photographers that explores current global issues through documentary photography, is releasing its second edition. This year, a group of Magnum photographers — including Chien-Chi Chang, Zied Ben Romdhane, Salih Basheer, Myriam Boulos, Newsha Tavakolian, Antoine d’Agata, Cristina De Middel, Emin Ozmen, and Sakir Khader — will produce an echo of Capa’s undertaking, a portrait of Generation Z.

“I think there’s great strength in using a format like the Generation X project for illustrating a global perspective. I absolutely believe that when you’re able to see candid images of the subjects in their daily lives alongside their biographical information and their answers to the questions, there’s a human connection: you are seeing and learning about an actual person rather than numbers in a statistic, or a conclusion applied to a general demographic,” says Murphy.

Using the same interview concept, Magnum Chronicles: GenZ is an homage to the Generation X project by Magnum’s co-founders, investigating the young generation today as they navigate multiple wars, migration, misinformation and authoritarianism.

To maintain the foundational values of independent storytelling and trusted collective authorship in a shifting industry, Magnum invites its audience to support the annual publication of Magnum Chronicles ahead of its latest issue.

Explore Magnum Chronicles here.