Watching Me, Watching You

The Edgelands Institute aims to get the world talking about creeping surveillance culture, reporting on six different cities, starting with Medellín. Colin Pantall reports on how and why they commissioned Magnum to bring "a different way of looking at and thinking about the subject."

Every time we leave the flat or the house, chances are somebody — a partner, a family member, a neighbor — is watching us. We get in a car, there are cameras upon us and we drive accordingly. We visit a supermarket or a department store and the eyes of cameras and security guards are watching us. Our faces, our movements, our identities are continuously being tracked through different forms of surveillance.

Few people think about the consequences of having all this data stored and potentially used against us. We have become blasé about surveillance, its digitization and the data that holds the details of so much of daily lives.

This apathy is what the Edgelands Institute seeks to address in its survey of surveillance and security in six cities across the globe. It’s a process in which academic research combines with community engagement, art, and the work of Magnum photographers to ask what surveillance means in our everyday lives.

The Edgelands Institute was initiated by Yves Daccord, a former CEO of the International Red Cross, and co-founder Beatriz Botero Arcila, an academic specializing in privacy law, surveillance and data governance. They met on a fellowship at Harvard where Daccord became fascinated by the ways in which surveillance and data could be used for both divisive and unifying ends.

“We selected six cities at the beginning, each with a different security context and story,” says Daccord. “We chose Medellín because it was once known as the most dangerous city in the world, and Geneva because it’s very small but has an amazing international footprint. Nairobi is fascinating because it’s divided along different lines, and the way the mobile phone is used to transfer money is far more dynamic than almost anywhere else. Singapore has a straightforward and tough social contract. Beirut was chosen because it’s completely fragmented along family and group lines, and Chicago has a specific geography, which is very much based on segregation.

A different Magnum photographer will work in each of the six cities, exploring some of the themes and issues surfaced in the reports. Magnum will also run a bespoke education program in each location, ensuring that some of the thinking and learnings on the subject are shared with locally-based photographers.

"The police, the cartels, and the youth are using technology for their own purposes."

-

The first to complete is Peter van Atgmael, who shot in Medellín in the spring. Thomas Dworzak recently began working in Geneva, and Lindokuhle Sobekwa is due to photograph the Nairobi leg of the project. (The photographers for the remaining cities have yet to be confirmed.)

“We wanted to look at how people and communities were experiencing the tradeoff between security and digitization. There are a lot of expert voices working in AI and security, but we didn’t want to become another expert voice, so we decided to make a pop-up institute. This means it will disappear after five years. It also means all our activities will be short and specific.”

In Medellín, the first city in the Edgelands program, the process began with local consultation. “The aim of Edgelands is to research and understand better at a grassroots level the impact surveillance and data has on society and its citizens,” says Sonia Jeunet, the Education Director of Magnum Photos, who oversees the agency’s participation in the projects.

“In each city, a team of researchers and psychologists carry out interviews to understand how people are using surveillance technologies and the effect of this technology on people’s daily lives. This is written up into a report and this is where artists and Magnum photographers come in to give a different interpretation of very academic reports.

“In Medellín, which is a city with a history of drug-related violence, and where the police are like a de-facto military, there are a lot of surveillance cameras. And the cartels themselves have a lot of surveillance cameras as well. One thing that came out of the report is that young people have created apps that help them monitor which areas of the city are safer than others. So technology and surveillance work in these three ways, where the police, the cartels, and the youth are using technology for their own purposes.”

"Who is watching whom? What data is being recorded? And where that data is going, and how it is being used?"

-

So here there are positive and negative aspects to surveillance. It can be a tool of control, but in the hands of Medellín youth, it is something that creates community and connects neighborhoods.

“Photographically speaking, this project is not really obvious,” says Jeunet. “So the aim for Edgelands, in partnership with Magnum, is to encourage people to have conversations about this topic [and it not just be] a dry, academic report. And documentary photography can do this.”

That was the challenge van Atgmael faced when he arrived in Medellín. “The more I talked to people, the more I understood that it was a case of formal and informal surveillance, and everyone watching one another,” he says.

With the help of Juan Fernando Ospina, a photographer and journalist, van Atgmael began photographing different aspects of surveillance; accompanying the police in their patrols of areas like Medellín’s notorious Bronx; from the perspective of neighborhood drug gangs; and also from an informal point of view.

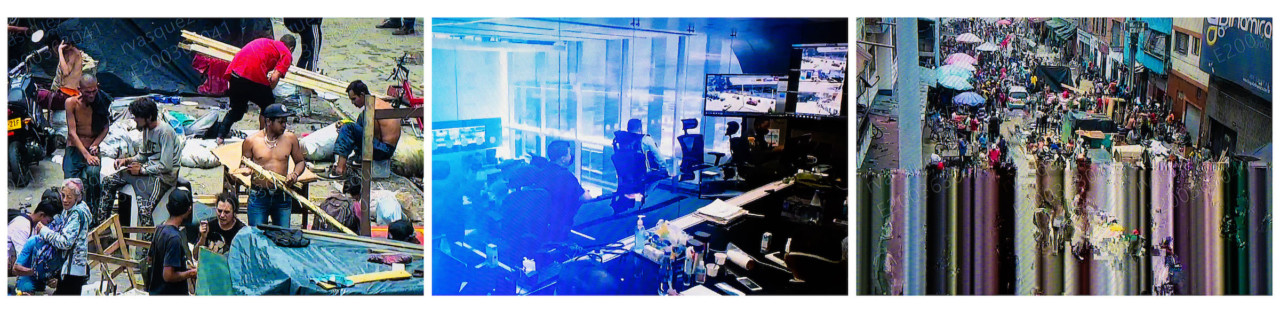

“The formal surveillance that you see in the pictures is a network of security cameras, both state-run and privately owned, that essentially dot the landscape just about everywhere you go,” says van Atgmael. ”You get the impression that nearly every kind of square inch of the city seems to be surveilled.”

"No matter who you talk to, whether it be the government and the police or the gangs, they always use the same rhetoric, that the surveillance is for people's protection."

-

In van Atgmael’s photographs, you see banks of screens lined up showing city streets — the selection of where cameras are located indicating a hierarchy of security that maps onto the demographics of the city. There are screenshots of arrests, photographs of police patrols, and repeated images of cameras.

“You get to the edge of the barrios outside the city center where the government doesn’t maintain any meaningful presence, doesn’t really patrol, and you find an area largely controlled by the drug dealers and that network of the black market. That’s where the state surveillance ends. And then that’s where the informal surveillance begins — of kids acting as lookouts for the gangs, or individuals from the neighborhoods looking for outsiders.

“It was striking that no matter who you talk to, whether it be the government and the police or the gangs, they always use the same rhetoric, that the surveillance is for people’s protection. But ultimately, the surveillance is there for both these organizations to be able to do their jobs more effectively with varying degrees of responsibility and fidelity to the rule of law.”

Van Atgmael traveled on police patrols and added his camera to the phones, body cams, and CCTV cameras that record the city. He became a surveyor, and his images show people’s response to this in sequences of gazes being returned by the gazed-upon as he accompanies the police as they raid bars and harass sex workers in the poorer parts of the city. Here, van Atgmael recognizes he is part of a surveillance that is a divisive expression of power, and his camera is met with hostile gazes.

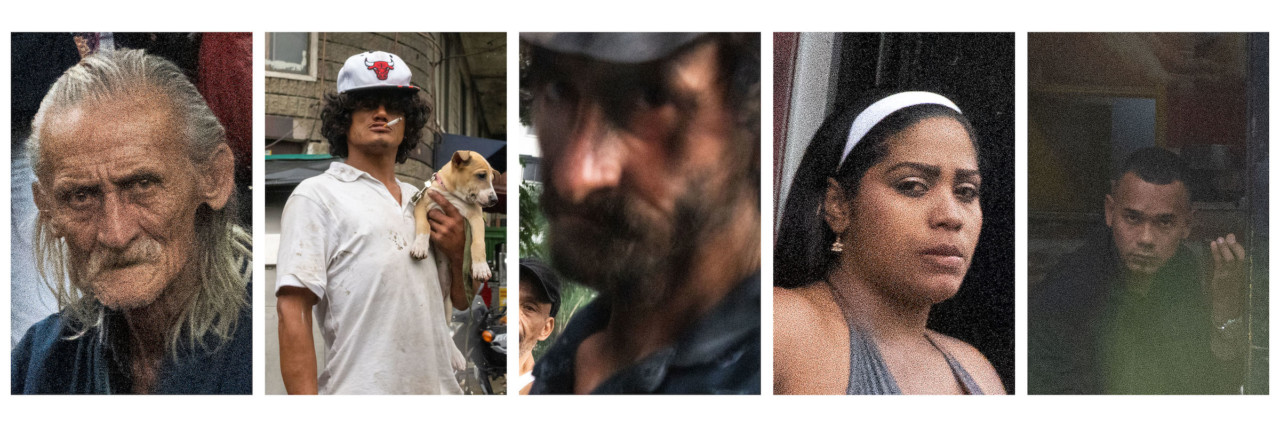

I’ve never been to a place where I felt as consistently watched as in Medellin. The various layers of surveillance, from technology, gangs, law enforcement and the regular citizens creates an unnerving atmosphere. I began to surreptitiously take images of people watching me with a long lens of shooting from the hip and assembled them into grids.

He also shows the ubiquity of informal surveillance. People stand on street corners, they look down from balconies, they watch what’s going on. Van Atgmael does the same, providing a Rear Window-like vignette of the balcony life of Medellín society. His photographs exemplify the key Edgelands question of who is watching whom, what data is being recorded, where that data is going and how it is being used.

“Surveillance has always been with us,” says Daccord. “Neighbors have always watched us. What is new is you have people watching you who are not at the heart of your social network. You don’t know where your data is going. You have data gatherers that store information. What does that mean for us as a community, how is it shaping us in a very specific way?

“We know AI and facial recognition can work in a biased way. It’s a question of, ‘Why are we surveilling?’ ‘What are we surveilling for?’ We don’t know at the moment. At the moment we focus on the data and how it’s managed. If we let things go, data will be used to create more segregation.”

At different points, I used a long lens on my camera to mimic some of the surveillance tactics in Medellín. This is a picture of a guest at a wedding taking a selfie. Despite the ubiquitousness of surveillance camera technology on the streets, the biggest scandals in recent history in Colombia have revolved around government surveillance of cellphones of journalists, activists, and opposition members.

The work that Magnum photographers are making for Edgelands is helping to create visual perspectives that provide entry and discussion points for these questions, says Daccord. “There is something three-dimensional about those perspectives. It brings a different way of looking at and thinking about the subject. Photography can challenge you and help you to think differently. I love that.”

“I personally think we can learn from Medellín and the way they are organizing their department of security and their coexistence. I like the way that security is being used not to separate and segregate a people but to find a way to find the right balance and the right rules to live together, at a time when most rules to do with the digitization of security are to do with segregation.

“We have the power to segregate entire populations in real-time. We have seen that in China during Covid, we see that in Israel, we see that in other countries, and I think it’s coming to Europe.” He gives the example of the sizable populace of Europeans who don’t have access to the banking system, and who might easily be shut out of travel systems, or even the ability to walk freely around a city, based on their data — or, rather, the absence of it as an access tool.

"Photography can challenge you and help you to think differently. I love that."

-

“That’s security and segregation, but what I’m interested in is security and coexistence. The idea is to create a movement that can organize themselves, and that people in cities feel it is possible to have a conversation about this very complex issue.

“It’s a conversation about how we live together. It’s about creating a collaboration between cities. My main aim would be that some cities that we’re not working with start creating their own methodology about these questions.”