It’s Okay to be Quiet

In part one of a frank and honest interview, Jacob Aue Sobol tells Colin Pantall about why he stopped making pictures following his breakdown, and why he's returned to the pictures he made in Greenland two decades ago with his new book, James' House.

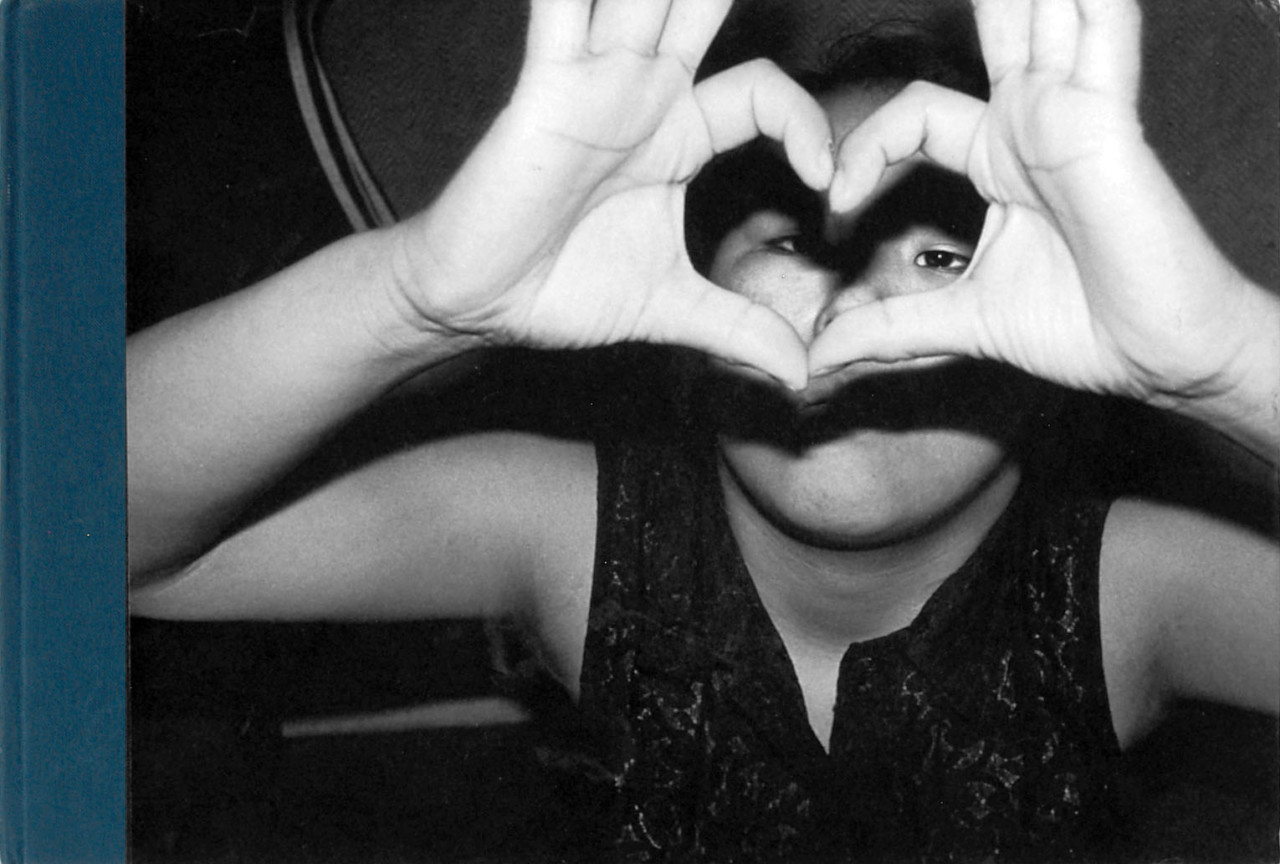

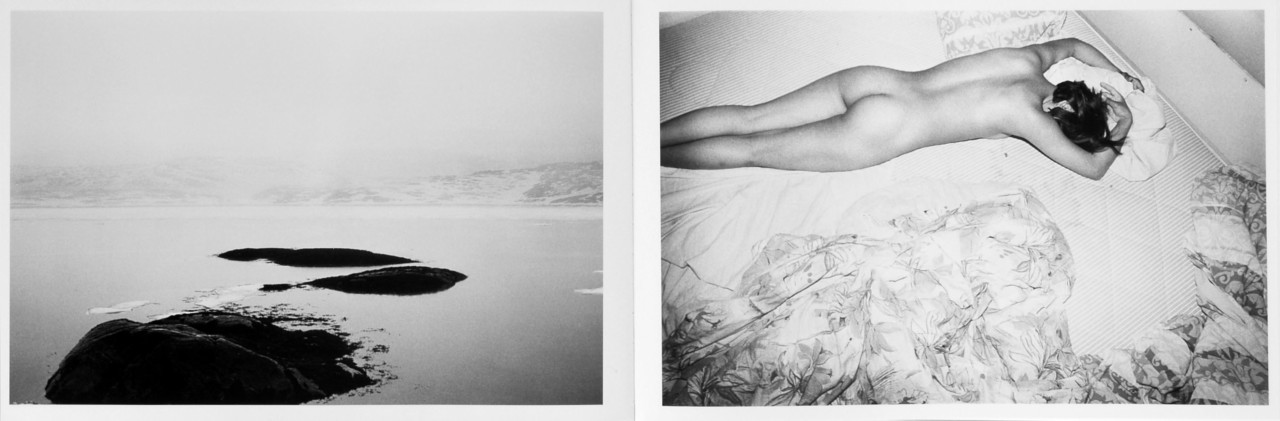

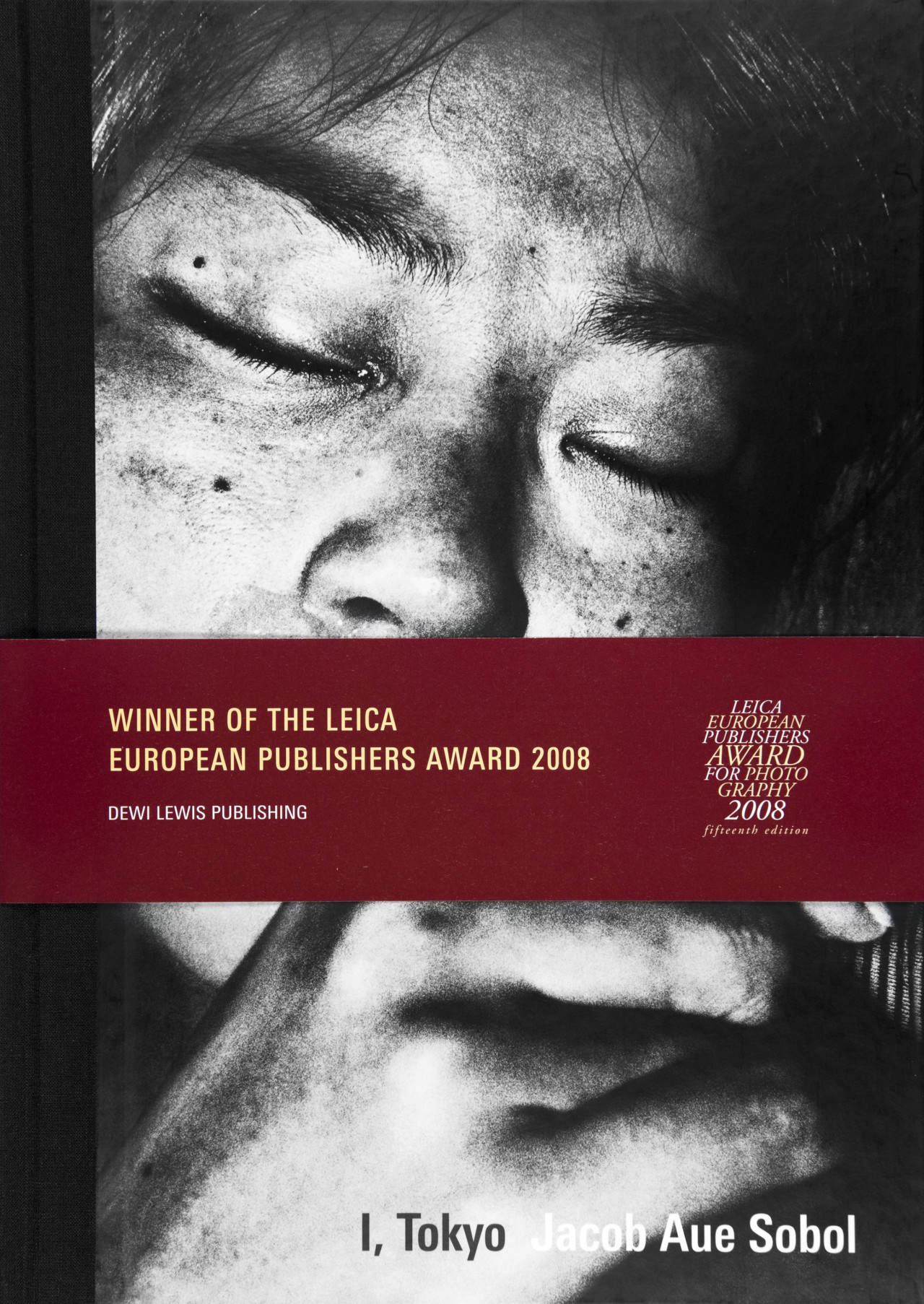

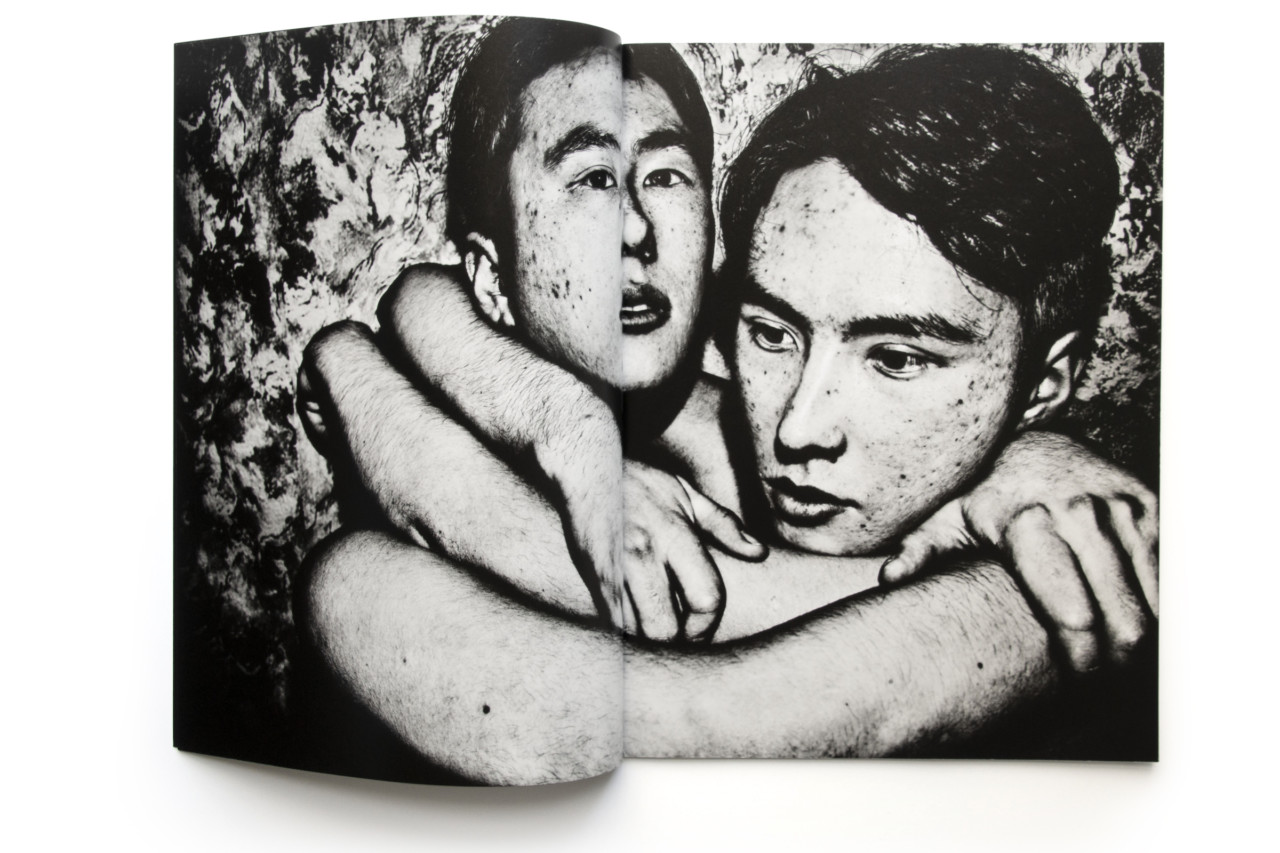

In 1999, Danish photographer Jacob Aue Sobol travelled to the isolated settlement of Tiniteqilaaq in East Greenland. He fell for a Greenlandic girl called Sabine. He made a book about her.

“I’m in love,” read the introductory text. “Sabine is 19 and I’m 23. I’ve decided to stay in Tiniteqilaaq. I want to be a hunter. Shoot seals and catch fish. Learn the language. I’ve stopped taking photographs.”

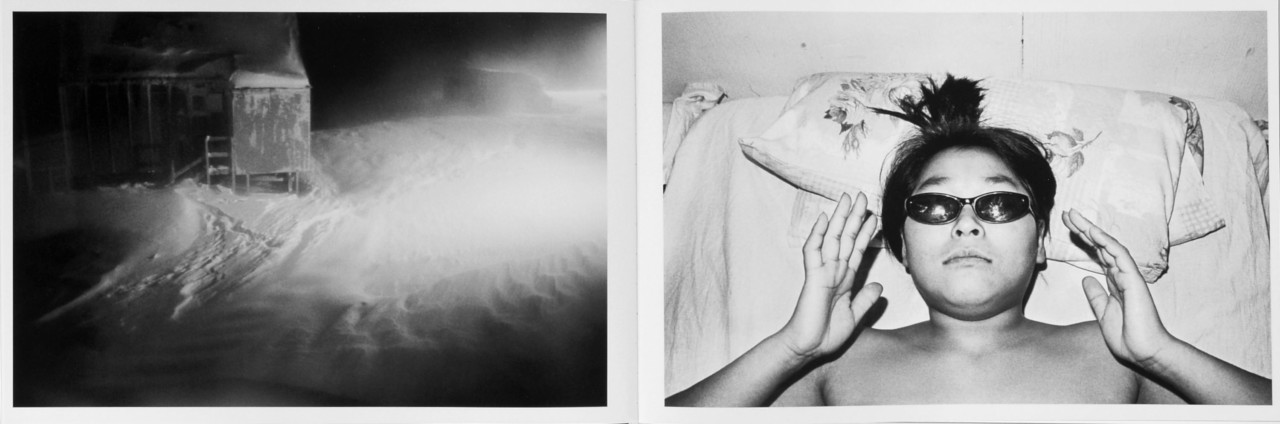

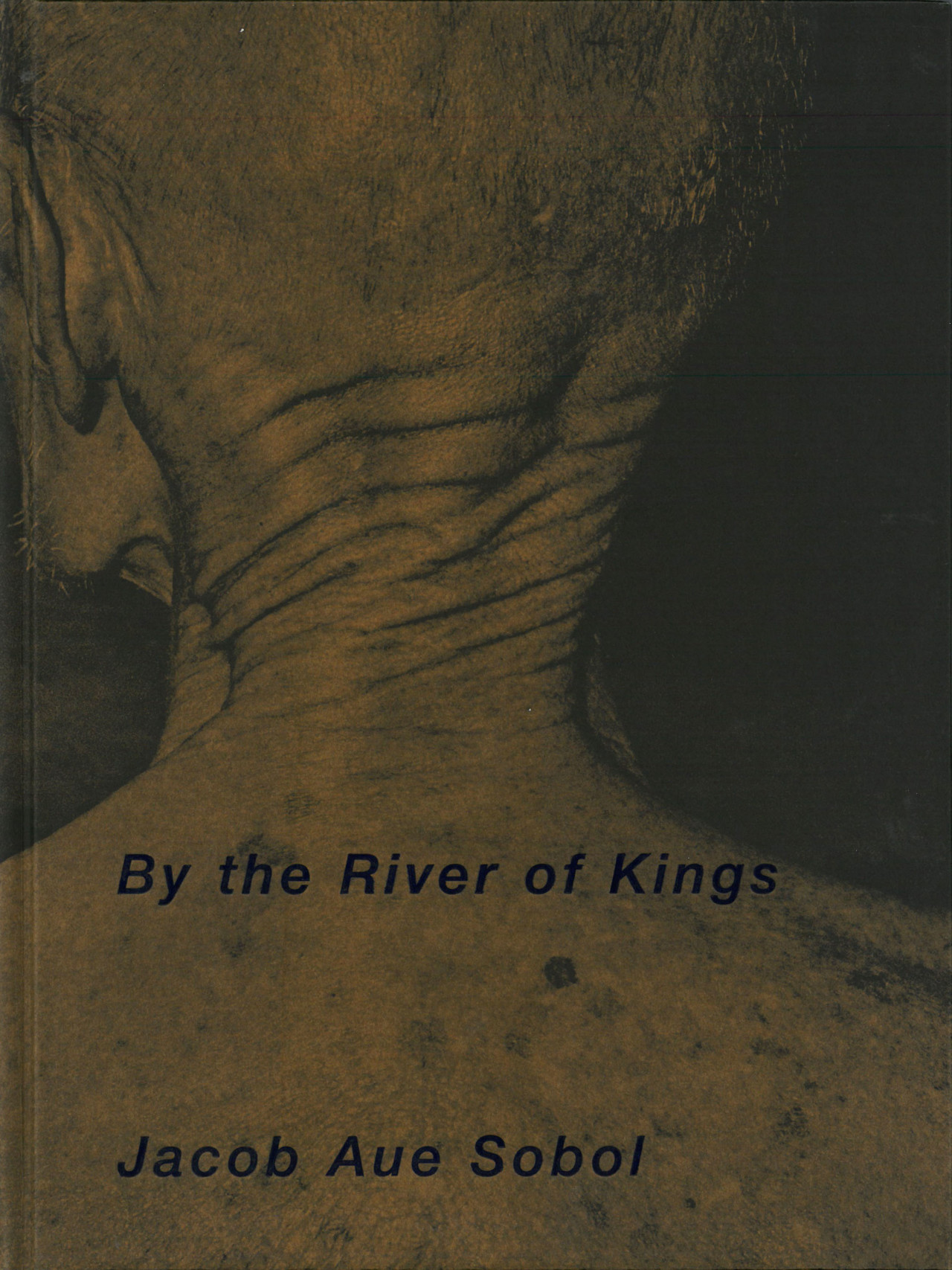

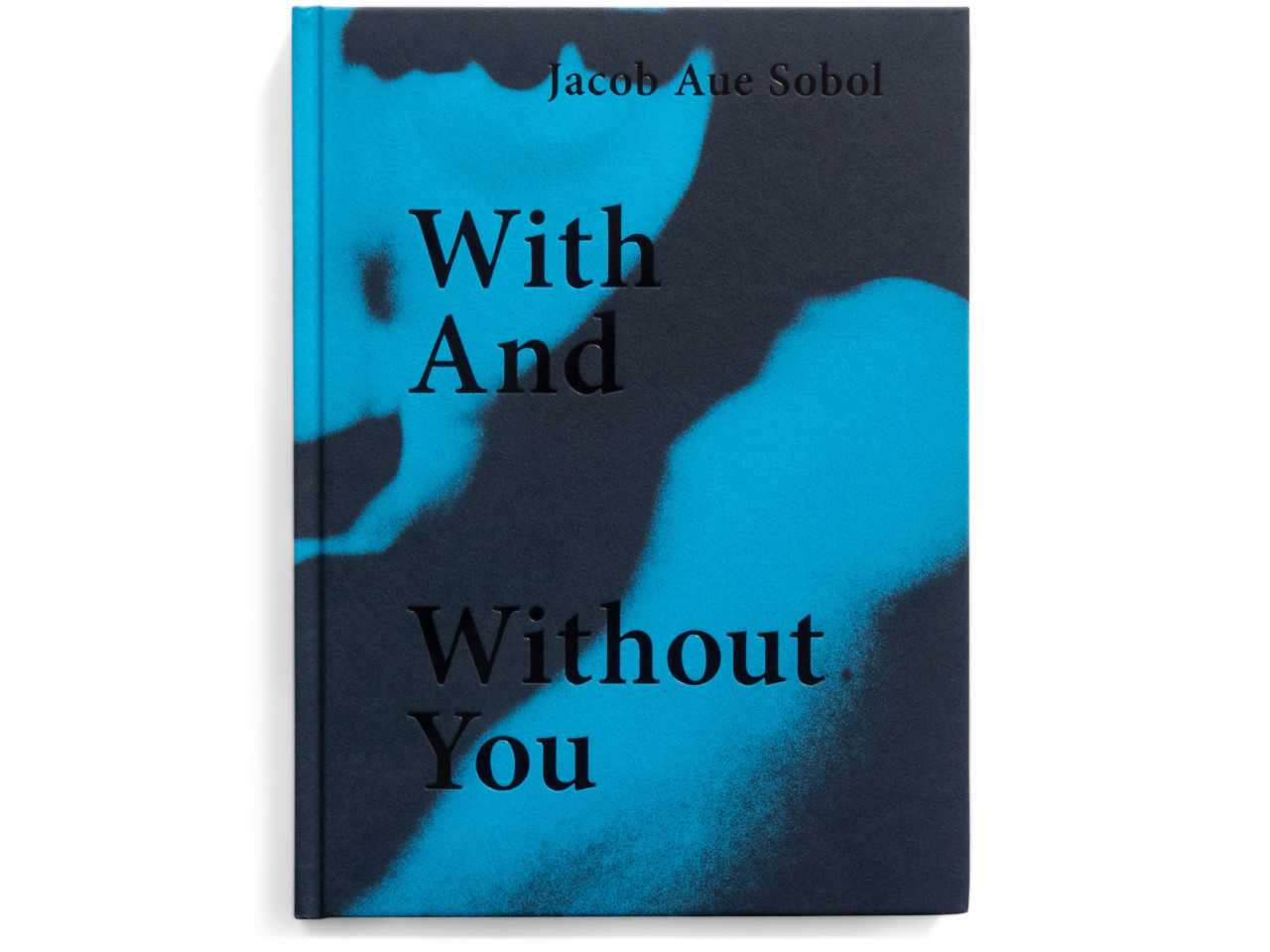

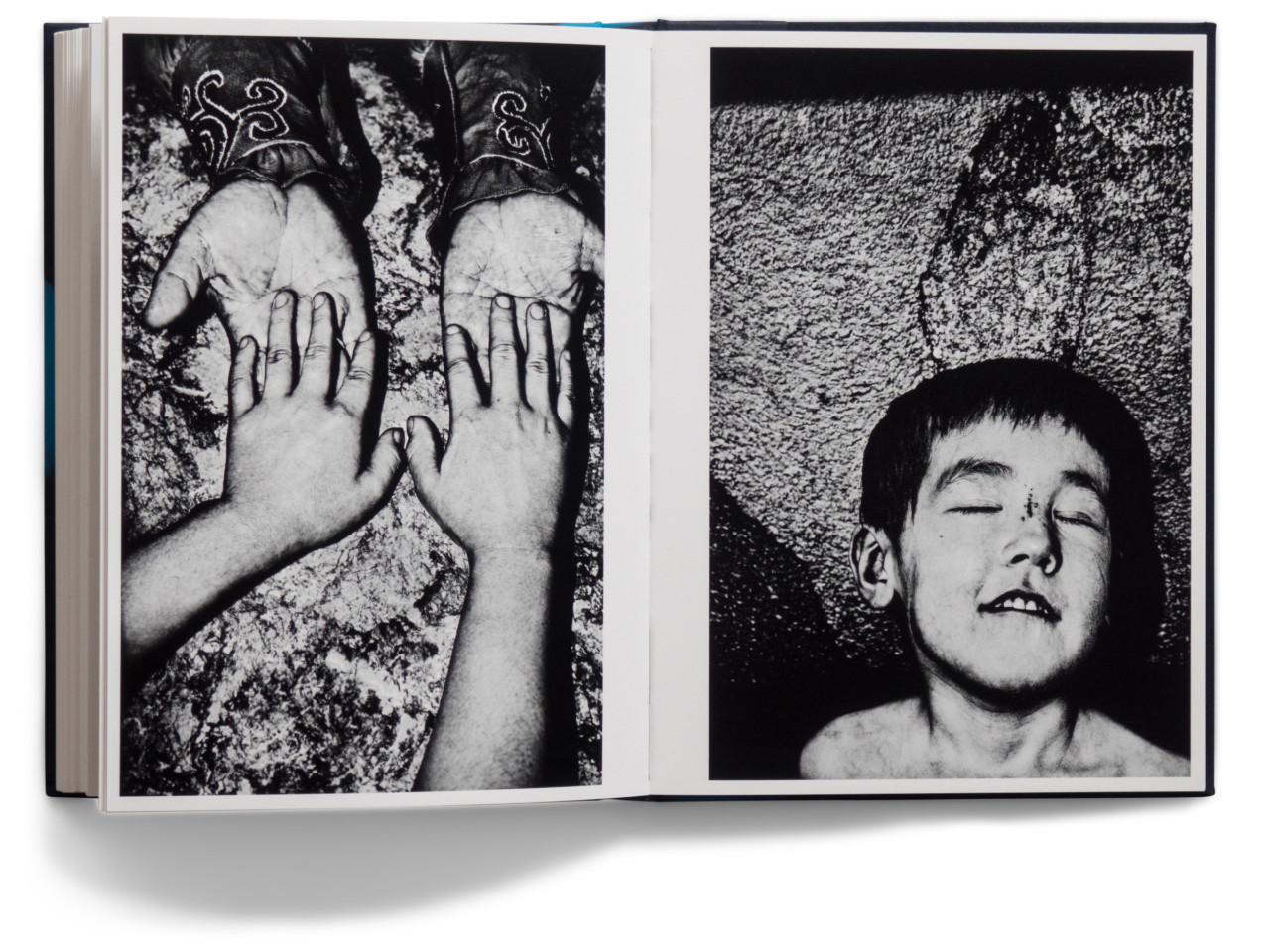

Now, 18 years after Sabine was published and became something of a cult classic, Sobol is making a new book, this time about James, one of the men who taught him to hunt and fish, the man whose home he spent so much time in. It’s a book that shares the same sense of immersion — within home, and within a land that time forgot — that made Sabine such a special publication. It’s a book that has embedded within it Sobol’s own ideas on what photography can be, and his struggles with how those ideas manifest themselves in his recent career.

In an interview from his home on the Danish island of Fejø, Sobol tells me about Greenland, fishing, and photography, and why he’s returned to the pictures he made two decades ago. “I first went to Greenland after my father had died in a traffic accident,” he explains. “It was a very brutal thing. My father had given me this book by Thomas Frederiksen called Grønlandske Dagbogsblade, which was like a diary of daily life in Greenland with these very minimalistic drawings. It had always been dear to me, but even more so after he died.

“It was a very difficult time. My father was hit by this truck, and suddenly he was gone. The whole family was split by that. We all reacted in different ways.” Sobol’s twin brother travelled to central America and started working at a children’s home, while his sister studied in Germany. He stayed with his mother, and continued his own education as a photography student at the renowned Fatamorgana school in Copenhagen.

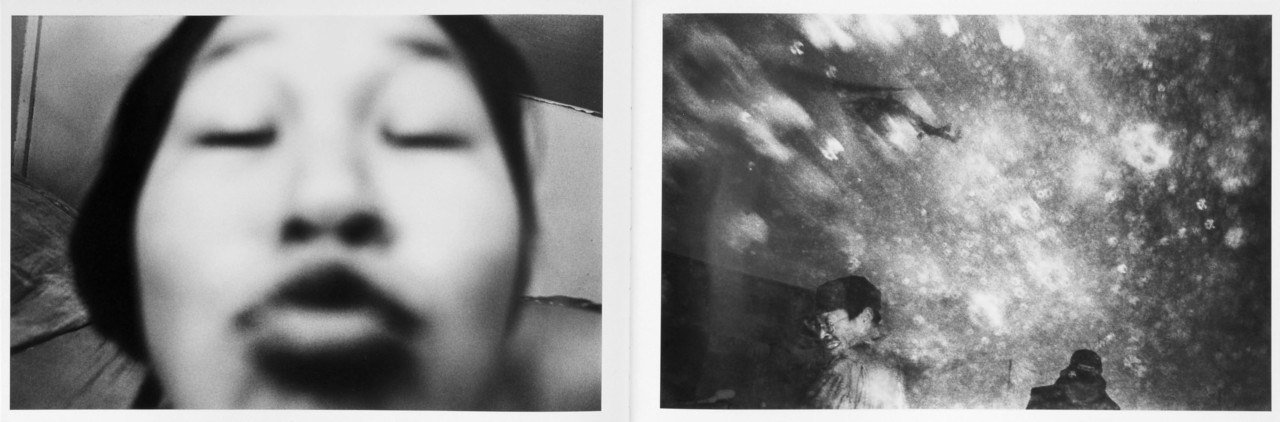

“I was experimenting in different directions, but one thing that changed my perspective was studying under Anders Petersen in a one-week course. He opened a door for me. I discovered that it’s really not about taking pictures. It’s not about projects. It’s about living. It’s about being involved with the people you photograph. It’s not a thing out there; it’s a part of you. And the camera is just a tool that you choose to use.”

"It's really not about taking pictures. It's about living. It's about being involved with the people you photograph."

-

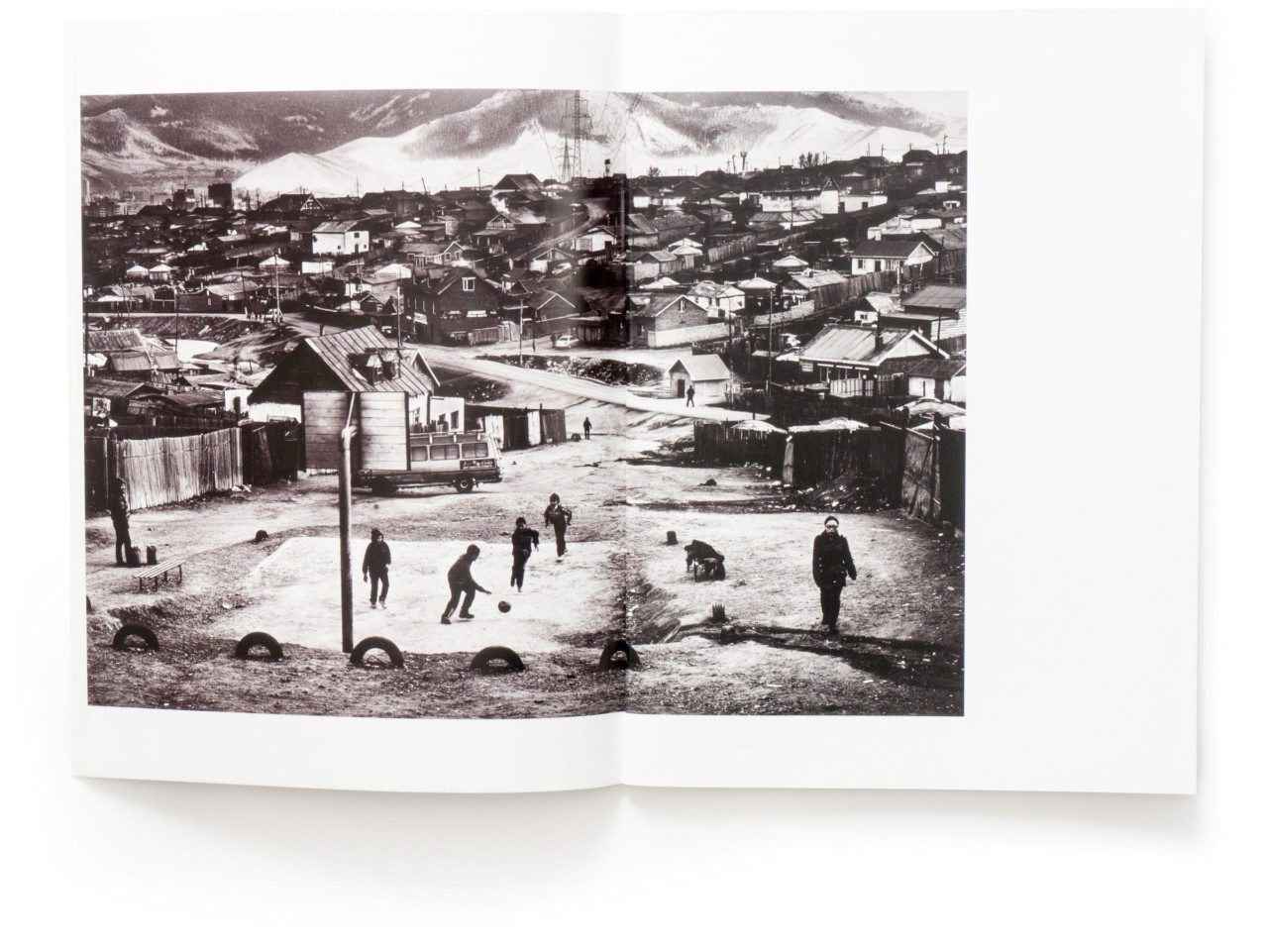

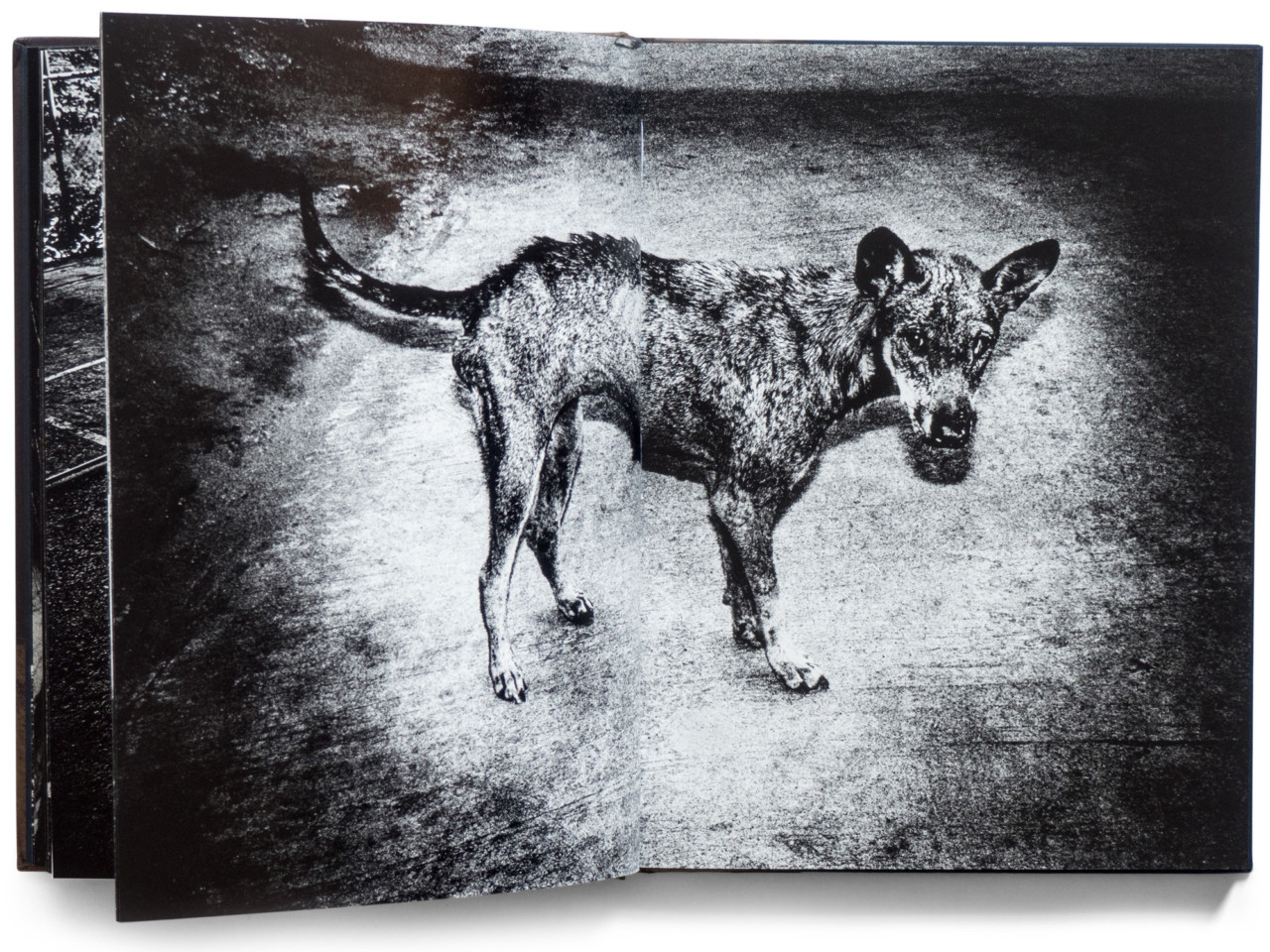

He feels that the first real pictures he took as a photographer were those in Greenland. “Today, I still go back and I look at them, and I see that everything that I did since — or have been looking for — is there in those pictures and in that place. I need to remind myself why I take pictures and how I take pictures because, after Greenland, I had periods where it became too much about photography again. There was the process of becoming part of Magnum, which makes you more of a photographer. Then I was in Tokyo, Bangkok, Siberia. I was producing a lot of work.

“Its not that I dislike it. I always felt that even though I produced a lot, I was always able to create a close contact with the people I photographed, if only for a short moment. I always had the feeling that it was not only me looking, but I was sharing an experience with the subject. I feel I create this space by focusing on the things we have in common as humans — our emotions — and not all the things that are different and which divide us. These things usually only exist on the surface.

“But, of course, it will never be the same as when you photograph the love of your life or your best friend. So at some point I felt like I was producing too much. I was becoming like a machine. And then I collapsed.”

He became clinical depressed in 2017, having worked nonstop for 15 years, amassing an archive of half a million pictures. “I couldn’t move; I was paralyzed. And it was very strange to experience, because I was used to having a very strong will. And then all of a sudden, I couldn’t go out and buy a litre of milk. Even now I don’t understand it, because it’s something that you can only feel when you are in it.”

“My [now] wife helped me, and my mother also pushed me to go running. Exercise helped me get back on my feet. But clinical depression is something that you have to live with because it’s never going to go away completely. It’s somewhere inside you with all the traumatic experiences we have in life. They stay with us. It’s a matter of finding a way to live. I need to respect more what kind of person I am and ask why I pushed myself so much to do all this?”

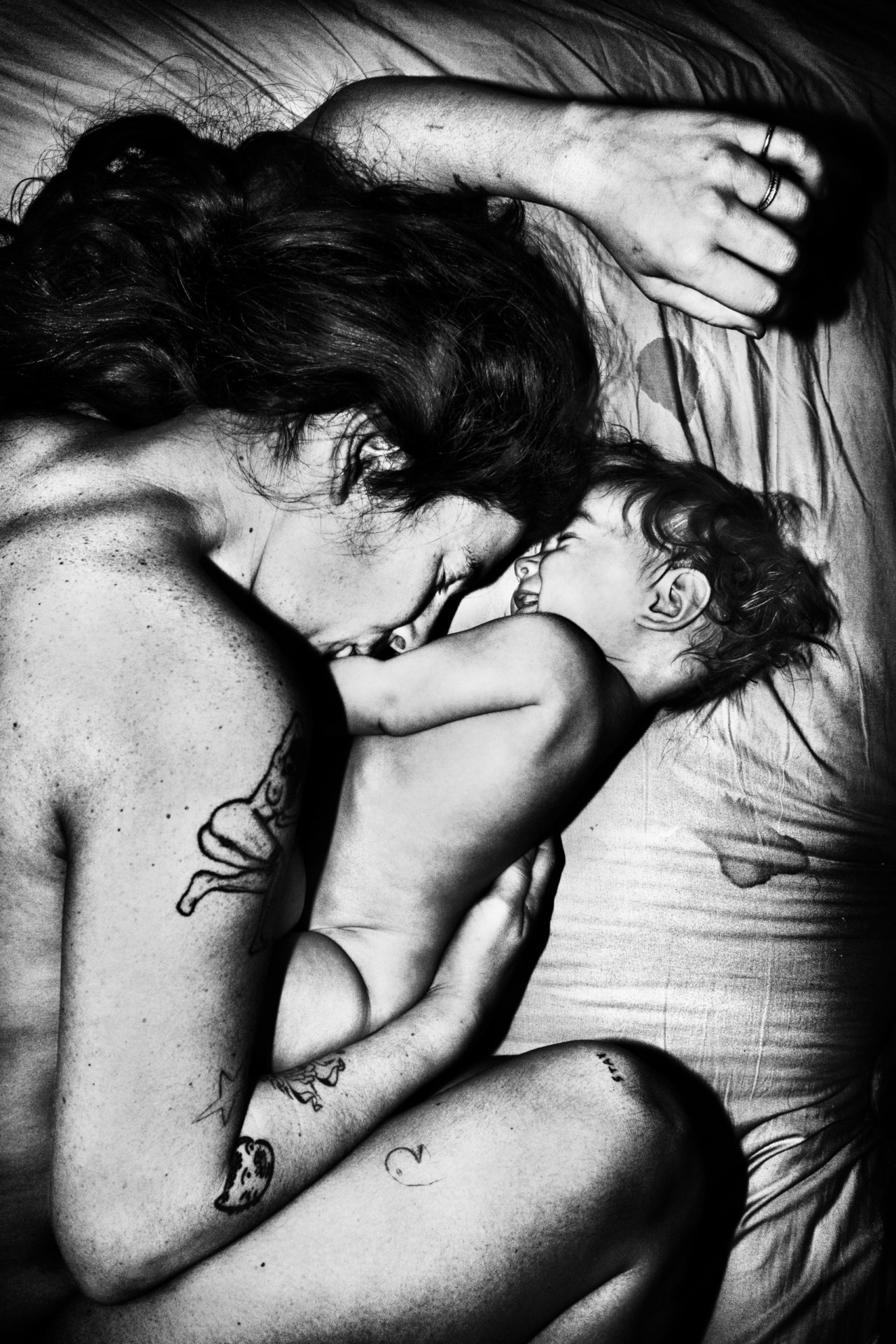

In the years following his collapse, Sobol got married, had children, and moved to a Danish island where life follows the rhythm of the sea and the soil, part of the process of his rediscovery of the photographic rhythms he experienced when living in Greenland.

”I haven’t taken any pictures since 2017, except for photographing my own family. I didn’t take any pictures at all the first two years, not one single one. But when my daughter was born, I felt like taking some pictures again. But now — and here is the connection back to why I started to photograph — it was someone I loved. And that inspired me to start to take pictures again.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen with those pictures, but it’s just a great feeling to have photography back to that point where it’s not about the photography or the project, it’s about life and love and the close connection you have with the people you spend your life with.

“So, I’m going back now to those Greenland pictures, which are about being in a place where I photographed what I experienced and what I loved, and it’s fantastic. But the rest — the last 20 years? What happened then? I mean, maybe I can be honest and say, no, I have not been able to take that kind of picture again. I think that’s also why I’m doing this book now.”

In part two of this interview, published here, Sobol talks about his latest book, James House, in which he returns to his work in Greenland from two decades earlier, but with an altogether different focus….