AIDS at the Ambassador Hotel

Paul Fusco’s visual account of residents living with AIDS at the San Francisco hotel that became their refuge

In 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) detected a rare form of pneumonia affecting five young homosexual men in Los Angeles. The next month, The New York Times reported on a “rare cancer observed in 41 homosexuals.” While HIV-1 strains were already known, this was the onset of the AIDS epidemic.

Paul Fusco was living in the San Francisco Bay at the time, “witnessing the crisis unfold from the very beginning,” says Marina Fusco Nims of the Paul Fusco estate. As the epidemic unfolded, “he was deeply troubled by the federal politicization of the epidemic and the devastating lack of support for those suffering, a neglect rooted in society’s disregard for LGBTQ+ lives,” she adds.

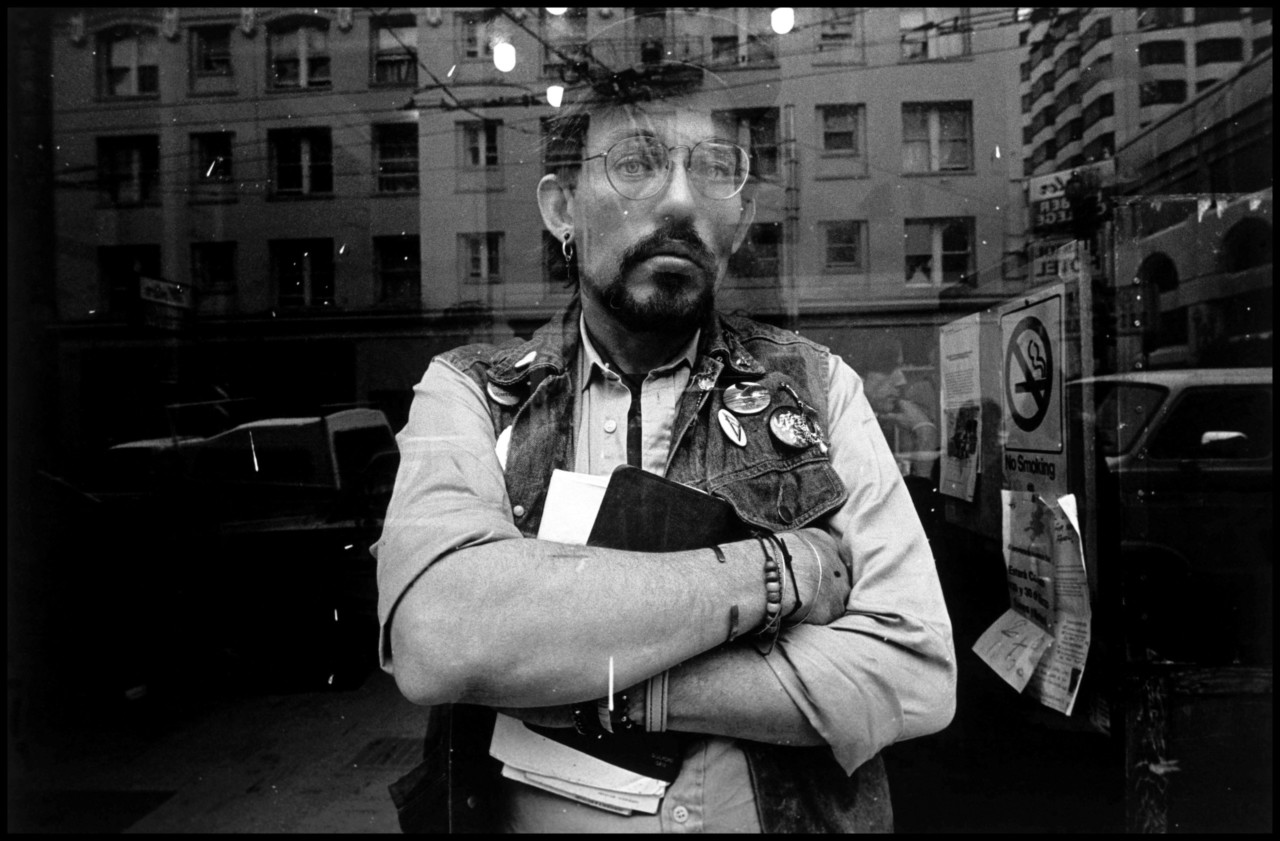

Beginning in the late 1970s, LGBTQ+ activist and homeless advocate Hank Wilson — who himself was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987 — began leasing four hotels in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, including the residential Ambassador Hotel. Under the management of Wilson and Tom Calvanese, the Ambassador opened its doors to marginalized, low-income people with AIDS, many of whom suffered from trauma, drug and alcohol abuse, and had been abandoned by their families.

“The Ambassador became well known as a safe harbor for anyone with AIDS and attracted them from all over the state and beyond,” Paul Fusco said. “Unlike others, Hank did not kick them out onto the street but tried to help those who had been stricken. His compassion attracted other sick men and women and his hotel became a refuge.”

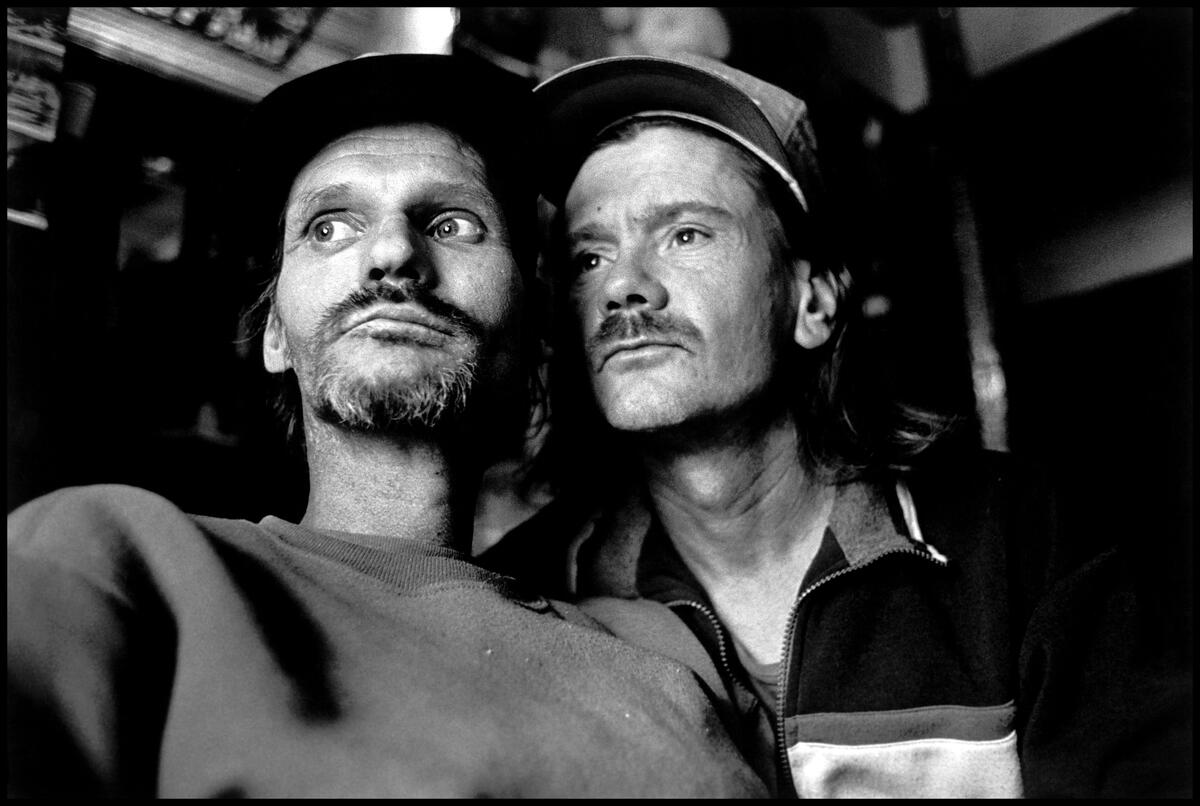

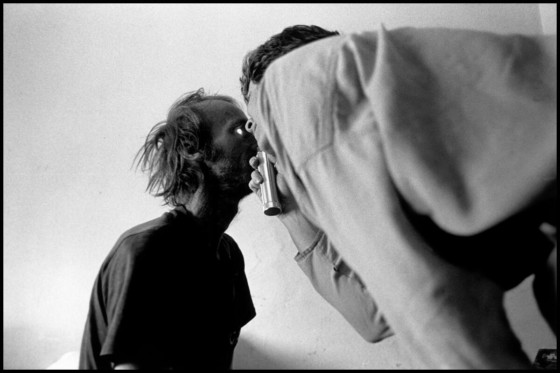

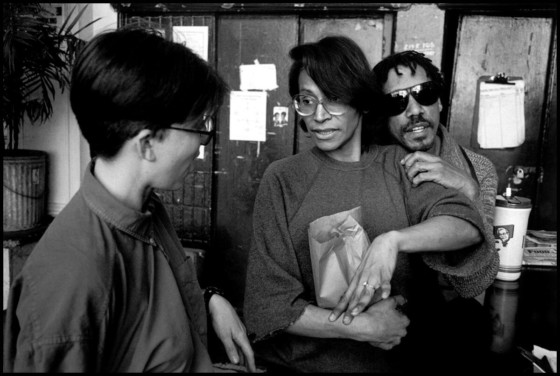

In 1993, Fusco began creating a visual account of the residents living with AIDS, as well as the staff, healthcare workers, volunteers — some of whom had AIDS themselves. Wilson’s initiative to provide not only a safe space but to bring social services and basic health care to the residents became a model for harm reduction within San Francisco’s LGBTQ+ movement.

“Fusco entered the rooms and corridors where residents lived, socialized, received care, and formed relationships. The portraits he captured honor the full humanity of his subjects, treating them with dignity rather than reducing them to symbols of suffering,” said Fusco Nims.

“We made a conscious decision to work with people with AIDS early on, and that was especially important because other agencies wouldn’t work with people who had substance abuse and alcohol problems,” said Wilson.

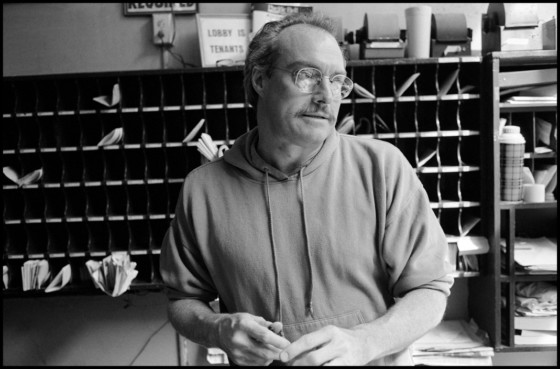

Wilson, who “treated his guests as friends” according to the photographer, arranged for agencies to provide hot meals, laundry services, health check-ups, and psychological support to the Ambassador’s residents.

At least one thirds of the residents in the 150-room hotel were HIV positive or were living with AIDS.

“There are times when you’re either going to start crying or you’re going to laugh about something. I have HIV myself, my lover has it, he’s sick. Most of my best friends are dead or are very sick. I know that I don’t have time to grieve anymore. I have to focus on staying alive myself and dealing with the people that are living around me and trying to help them survive. This is an epidemic. People are dropping dead left and right,” said Calvanese, the hotel’s co-manager, in “Life and Death at the Ambassador Hotel,” a 1994 news documentary about the Ambassador.

In the documentary, one resident calls it “a sanctuary,” despite some of the everyday tensions — clashes between residents, episodes of mental illness, and inevitably, death. “To do this work you have to be able to open up your heart,” said one of the Ambassador’s social workers.

Among the nurses that contributed to the effort was Val Robb, who helped bring medical services directly to the hotel, so that the residents didn’t need to struggle to find clinics to receive routine care. She recalls that one resident went to a hospice, yet “he came back here and lived for another year, and chose to die here with his friends and family. Well actually, we were his family,” said Robb. She believed that the common denominator of the care providers was a “lack of judgment and a willingness to help”.

Records from the staff log books in 1994 detail their selfless care towards the residents on a daily basis, from helping to rearrange their rooms to supporting them through drug addiction, depression, and suicidal thoughts.

Carolyn Jones, a visiting nurse, said, “There are a lot of people that I’ve met that don’t understand how I can work down here, and I think people who don’t understand that don’t realize that these guys down here are people too. Most of society tends to pass judgement on those people. Who are those people? Well, those people are me and you.”

Discover Paul Fusco’s collection of prints at the Magnum Store.