Boa Noite Povo

Cristina de Middel and Bruno Morais discuss their ongoing project which explores ecological and social extremes through the wildlife of the Brazilian jungle

A new photo series by Magnum photographer Cristina de Middel and artist Bruno Morais explores the extremes of human life, belief in mythology, and political feeling through depictions of nature. Working in Bahia, Brazil, the pair are composing a series focused largely around animals — wild, as well as domestic; in their home, and outdoors in the jungle of the Mata Atlântica. These animals appear alongside various interventions, from printed collage, to archival photographs, to mirrored surfaces and household objects — props and experiments which invite the viewer to question how they understand photographic representation. De Middel and Morais, who are married, have been fascinated with the wildlife of the area since 2017. They propose that an examination of the definition of nature and culture, through these motifs, and in the current moment, offer an apt insight into the “ecologic and social drama” of our current political and economic contexts.

In the following Q&A, the collaborators spoke to Magnum about the predictability of human nature, working responsibly with animals, and overlapping systems of science and belief.

Your text accompanying the work sets forth the idea of the cyclical nature of human development, civilization, and enlightenment. How would you characterize the ‘cycle’ we find ourselves living in now, generally speaking, but also in Brazil specifically? As living there seems to have been an impetus for starting the work.

Bruno Morais: It is very hard to not feel pessimistic when facing the current state of things around the world. In Brazil, for instance, after several years of social progress we are now living in a total dystopia. Still, if you can detach yourself from the human scale and observe the panoramic from an ecological perspective, you can clearly see the see signs of a cultural era that is coming to an end. And this is happening simultaneously with the syncretic rising of different groups that have been marginalized, and that are now becoming organized. In Brazil we never really had a democracy, we never reflected socially on slavery, or on the dictatorial period and its consequences in our daily lives, so perhaps this dystopia— this authoritarian, xenophobic spurt— is the fastest way to review and overcome the hypocritical varnish that covers the country. But it really feels like the end of an era.

Cristina de MiddeI: I think we are coming to the end of an era where profit has been the totem, and the truth is that it is not coming to an end because we realized it was wrong, but because our resources are exhausted and we have no choice. The profit party is over, and in my opinion this exhaustion and the stress that comes with it, is obviously visible in Nature and Wildlife but also in civilization. Brazil is living a period of constant tantrum and it translates into an irrational embracing of populist messages in an effort to respond to the survival mode that a majority of the population seems to have adopted as a routine. It is also not something specific to Brazil. I think in general, citizens worldwide, after years of trusting politicians and institutions, just want to be heard and, as a result, choose the person who shouts loudest to represent them. What seems to count is the noise you make, not what you have to say.

"We started this project right after the election of Bolsonaro as a president... We wanted to reflect on the dark times that the country was going through, but also wanted to avoid censorship and still pass on a critique"

- Cristina de Middel

How does looking at man’s interaction with and encroachment upon nature in Brazil reflect the nation’s tumultuous politics you allude to? And further – how did the nation’s situation inspire you to start this work in the first place upon arriving?

CdM: We started this project right after the election of Bolsonaro as a president. It was a commission from a Brazilian bank for a group exhibition around the theme of ‘The Night’. We wanted to reflect on the dark times that the country was going through, but also wanted to avoid censorship and still pass on a critique. The bank would never show images that carried a literal critique of politicians. So, by making it subtle and open ended, it became a much more global project. I guess we also soon realized, that the scale in the end did not matter, because we would still be shooting in our backyard to reflect on something much bigger.

"We wanted to add an extra political layer to the classical debate of Nature vs. Culture but we did not know it would become the series it is now"

- Bruno Morais

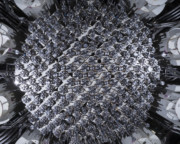

Can you explain a little how you chose to visualize this – the use of animals from around your new(ish) home, and the mixture of nature photography, posed still lives, and the utilization of archival images and paraphernalia?

BM: Initially, there was no conceptual framework or, at least, the idea was not as structured as it is now. The creative process has been purely experimental: we wanted to add an extra political layer to the classical debate of Nature vs. Culture but we did not know it would become the series it is now. Our house is full books, strange objects, old photos and other paraphernalia, but it is also located in a place that is full of animals and vegetation, so the experiment was in a way already going on. We just intensified it, and also documented it.

In that sense, I think we sort of played the role of alchemists who move half blindly in the search of transformative experiences.

CdM: We also wanted to do something at home, which turned out to be a good idea during the six months of confinement during the pandemic. It made sense because the way that animals enter the house and share the spaces within it is so natural, and anyway it doesn’t seem like we have much choice in the matter. I am far less used to this level of contact with nature than Bruno is, and to me the fact that you can see a banana tree grow a meter in one day is just mind-blowing.

You can almost sit and watch how life expands in slow motion. I immediately felt the tension between our presence and the environment and started looking for different ways to translate this tension. Of course we needed to make a reference to wildlife photography because— even if it has changed a lot, and the trend now seems to be showing animals with human emotions and reactions— photography and wildlife have a very interesting history together. The good wildlife photographer needs to be invisible and create a pure image that does not reveal their presence. It is one more of the areas of photography where the expectations on truth and neutrality are extremely high, and I am very interested in that.

"In a time where the relationships of power and photography are being redefined and when animal rights are finally being taken seriously, the technical aspect that was really challenging was not about the lenses or the flashes we could use, but finding the system that would make the minimal impact on our subject."

- Bruno Morais

Portraying insects, birds, reptiles, seems like it could be creatively —but also technically— quite liberating for a photographer who focuses on social themes. Have you found it easier to work with animals, or humans?

BM: You are right, but I would not say, however, that it is liberating because it is also compromising. The interaction with animals is relatively tense depending on the animal and in most cases you do not get the immediate feedback you would get from a human subject at the moment of the photograph, so you are completely in charge of the photographic act and your own ethical standards define the red lines. In a time where the relationships of power and photography are being redefined and when animal rights are finally being taken seriously, the technical aspect that was really challenging was not about the lenses or the flashes we could use, but finding the system that would make the minimal impact on our subject.

CdM: I find it equally difficult, honestly to work with animals or with humans, difficult in different ways. As Bruno said, we really spent a lot of energy figuring out how to affect these animals’ life minimally and all the decisions needed to be taken quite fast in order to liberate them as soon as possible. We had all the power, but we also felt all the responsibility, especially since our message was also about the action of man on Nature. We could really not replicate what we were denouncing and the line was sometimes extremely fine. We, for example, never captured an any animal: we only worked with those who entered the house themselves and we released them right after the “performance”. The whole thing was sometimes a bit stressful, so I admit that the plants are easier to work with!

"On one side you have Culture, as a human construct, with archival photography, as a record of what humanity has done. At the other extreme you have Nature, as an opposite to any ‘construction’, and wildlife photography as the attempt to record and capture Nature from a neutral point of view"

- Cristina de Middel

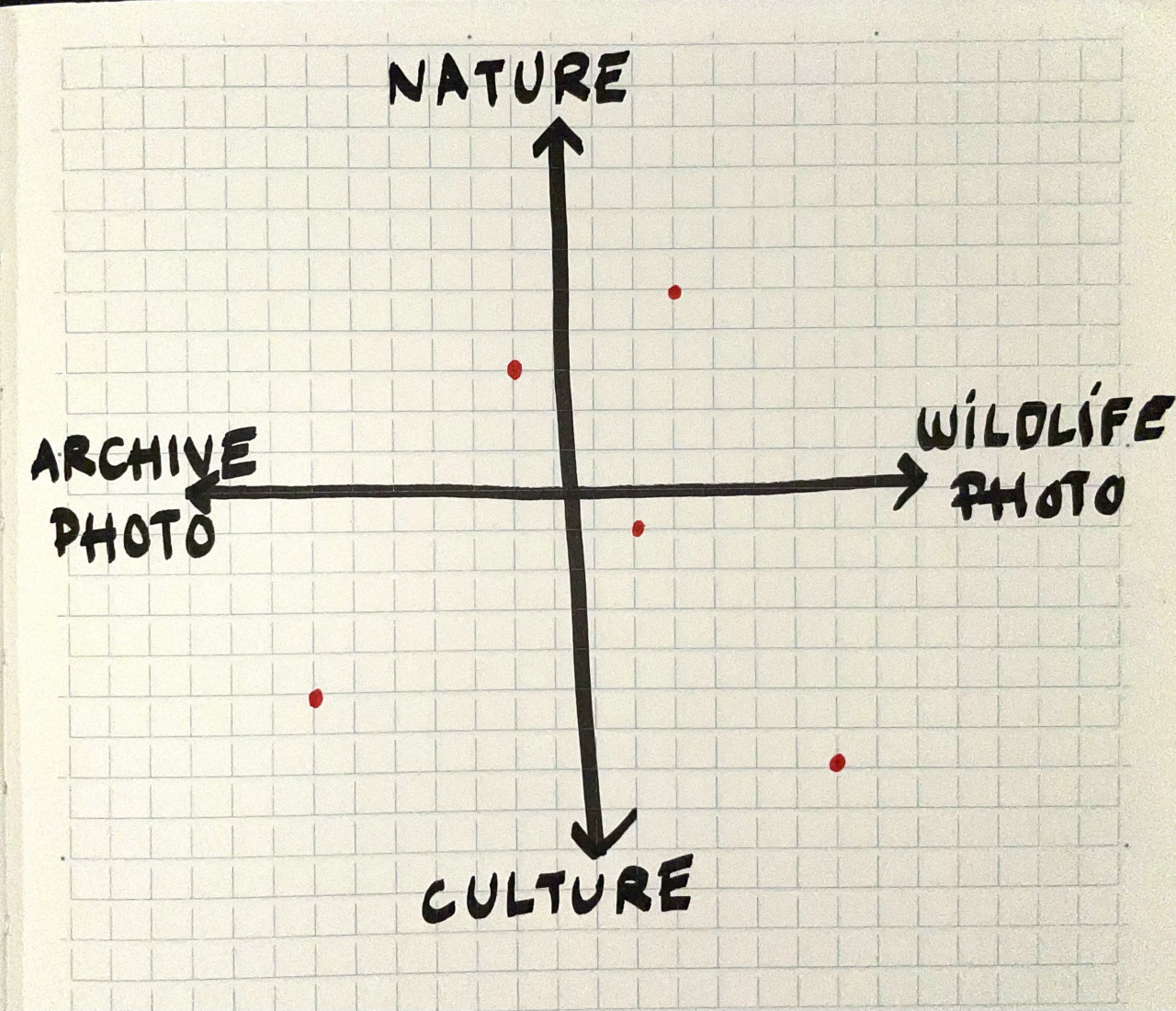

You shared a graph of sorts – two axes running from ‘Culture’ to ‘Nature’ and the other from ‘Archive’ to ‘Nature Photography’ – this seems an almost technical project in some ways: you are utilizing diverse tools and approaches to convey specific parts of a wider theme. With that in mind, can you explain how each of these distinct visual aspects of the work reflect aspects of the subjects you are exploring?

CdM: The graph and the text were presenting the framework for our experiments. It was, together with the introductory text, an initial statement that helped us kickstart the first ideas for images. On one side you have Culture, as a human construct, with archival photography, as a record of what humanity has done. At the other extreme you have Nature, as an opposite to any ‘construction’, and wildlife photography as the attempt to record and capture Nature from a neutral point of view. All the images we wanted to create had to find their position within the graph and we wanted to explore as many combinations as possible. I know it sounds very theoretical and brainy, but it really was just the beginning of the process, then things started unfolding very “naturally” and we started seeing this tension almost in anything around us. If you think about it, all the images in the world and all the things we do, are in dialogue with this conflict between Nature and Culture so we needed to shrink the frame a little bit if we wanted to make something meaningful and not generalistic.

"The thing is, that all this material— the photos, the magazines, the albums— they are being eaten by the humidity of the jungle. We constantly need to clean them to protect them from fungus and all sort of insects, so the invasion is real and nature is winning the fight every day at home... "

- Bruno Morais

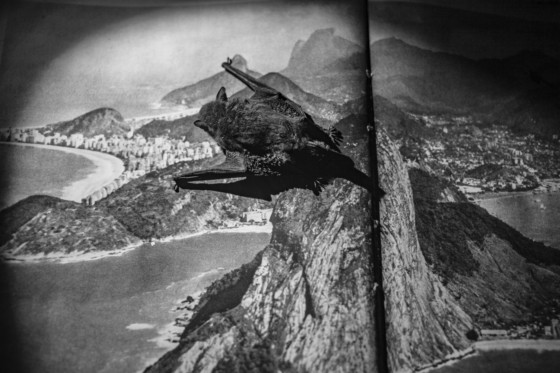

To dwell on the archival material – can you explain a little about these images, what they are and who the subjects are?

BM: These are images from our small collection of Brazilian albums, vernacular photos, and magazines. When we lived in Rio de Janeiro we would go to the “trash supermarket” (as they call it) or thrift markets to buy old photographs and magazines. It is not a big collection but there are interesting things in it, like the complete archive of a newspaper that supported the dictator back in the 60s and 70s, called Tribuna da Prensa. It conatins images of social life, crazy parties in the Copacabana nightclubs, and politicians, but also of the growth of the city with its favelas, and the launch of the first Brazilian satellite.

We started using these when the project was focusing on Brazil, but slowly shifted to looking at the more international news images that we could find in the pages of the same magazines and albums – things like the Space Race or advances in technology in general.

The thing is, that all this material— the photos, the magazines, the albums— they are being eaten by the humidity of the jungle. We constantly need to clean them to protect them from fungus and all sort of insects, so the invasion is real and nature is winning the fight every day at home. So maybe, in a way, we are also trying to record them, making more photographs to archive them, including the context of their degeneration.

The predominant feeling for me in the work – and something you mention in the text – is a sense of a return to occultism, to pre-scientific belief, and to ‘legends’ – to use your wording. It doesn’t feel to me like you are condemning this – is there for you both perhaps something positive to be said of these belief structures…? And if yes, how can they be of use to us today as a global society?

BM: Instead of the terms “belief structures” – which conveys an anti-scientific pejorative meaning, I would use “cosmogony of ancestral people”, acknowledging that these primitive societies do have complex scientific, philosophical and religious systems too, and that is continuously underestimated and ridiculed by the predominant white Western perspective. We want to question the idea of White Man having the exclusivity of the universal knowledge of the world thanks to his elaborated tools and how everything gravitates around that assumption. Now, more than ever, it is necessary to reflect on the idea of “cannibal metaphysics” (borrowing the term from the anthropologist Eduardo Viveiro de Castro) and to consider this body of ancestral knowledge as the most advanced that is now available.

CdM: I agree with Bruno regarding the language, as it is carries plenty of political dimensions, especially here. If we say “occultism”, we immediately think of late night esoteric shows where you pay and call to know your future from a cyber-witch wearing a ton of make-up, but we need to understand that indigenous and primitive knowledge is maybe not Cartesian, but it is still very, very “scientific”. A very obvious example is that most of the medicines that we use today bearing pharmaceutical logos, come from this ancestral knowledge, and that those people discovered the remedies thanks to the balanced dynamic they had with Nature. When we do not criticize this return to a world of legends and myths, we are actually saying that this Cartesianism and positivism that was put on a pedestal in the industrial era is what took us to this point of ecologic and social drama. I find it more coherent to see a god in the woods or in the waterfalls than to see it in some man that died on a cross (sorry). It shows a much needed respect for Nature that mankind totally forgot when it positioned itself in the center of the universe. This idea of not being the judges and the owners of everything could maybe save us faster than studying under a microscope the signs of the total collapse of the planet.

"I think our own marriage has evolved with each one of these projects. We come from different backgrounds and different cultures and it is sometimes difficult to not project the dynamics of our life in common into the work"

- Cristina de Middel

Could you explain a little how you work together – the division of the process, and the practicalities of creating work in tandem? What are the benefits of a collaborative process and project versus the potential drawbacks?

CdM: We were already used to working together. It has been a very interesting way to get to know each other better and also to understand our egos and weaknesses. I think our own marriage has evolved with each one of these projects. We come from different backgrounds and different cultures and it is sometimes difficult to not project the dynamics of our life in common into the work. What we do is to accept all the ideas as they come and to develop each one of them, even if we do not agree or if we do not think it will work. We judge the relevance of the idea only when it becomes an image and only when the editing process starts. I become Bruno´s assistant when we are working on his idea and he becomes my assistant when we are working on mine… and then we edit together.

The drawbacks are obvious and the situations can become tense, but we also have our own individual projects where we decide on everything, so even when things get ugly, there is always an escape door! Working together is maybe a very hardcore form of marriage therapy, but it’s one that is also quite productive. (Bruno does not want to add anything because he agrees!)