Tiananmen Square, 1989

Stuart Franklin reflects upon the nature of iconic photographs, and the events in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989

Stuart Franklin’s photograph of the famous ‘Tank Man’, as well as images of the Goddess of Democracy statue made in Tiananmen Square, are some of those which are often thought of today as a visual encapsulation of the events that shook China over 30 years ago: the long-running student protests, eventually ended by the People’s Liberation Army in Beijing, in June, 1989.

However, as Franklin explores in the following edited excerpt from his essay in the book The Media and the Cold War in the 1980s (Palgrave, 2018), his photograph was not the only one made of the Tank Man, and nor did his or the others spring to instant fame. Here Franklin reflects on the concept of iconic photographs – whether of the Goddess or the various images of the Tank Man – and the role that global media and political expediency play in making such images the ‘icons’ they are seen as today.

Before 1989 iconic photographs were normally seen as unique: attributed to one photograph by one photographer. Tiananmen changed all that. [A photograph of the statue named] The Goddess of Democracy, taken by an unknown photographer, has been described as iconic (Hariman and Lucaites 2007[1]). All four versions of the Tank Man image captured from a similar vantage point have also been described, at one time or another, as iconic, inviting the question: is it the photograph that should be described as iconic or the subject—or, as in the case of the Goddess of Democracy, the pictured object?

I happen to be one of the photographers whose image of the tank man first gained attention. Had a hundred photographers captured the tank man in front of the Beijing Hotel would all the images be iconic? Probably. The particular qualities of each version would be subsumed under the greater meaning connoted by the fetishized subject, echoing—I think it is reasonable to say—the various versions of Christ on the Cross, the Virgin of Guadalupe, Chairman Mao wearing his forage cap, or Babe Ruth at his last game.

Further, the assumption is that iconic photographs rise to prominence on the basis of the natural excellence of visual reporting. I suggest that the quality of the photograph per se is less important than the messages that such images convey, iconic photographs are accelerated into prominence due less to their formal excellence as photographs than to their fit with political expediency.

Protest

Between April and June, 1989, the world turned its spotlight on the gradual build-up of tension in China. The focus was on a student-led protest movement in Tiananmen Square which began after the death of reformist Hu Yaobang, the purged ex-general secretary of the Communist Party (CCP), who collapsed at age 73 after a heart attack on 15 April. The CCP was simplistically divided into factions favoring either conservatism or reform (Scobell and Wortzel 2005[2]).

On 16 April students marched from two leading Beijing universities to place a wreath at the Monument to the People’s Heroes—a 37.4 meter high obelisk in Tiananmen Square. Three days later Hu Yaobang’s portrait, painted at China’s top art school, joined the wreath (Wu[3]).

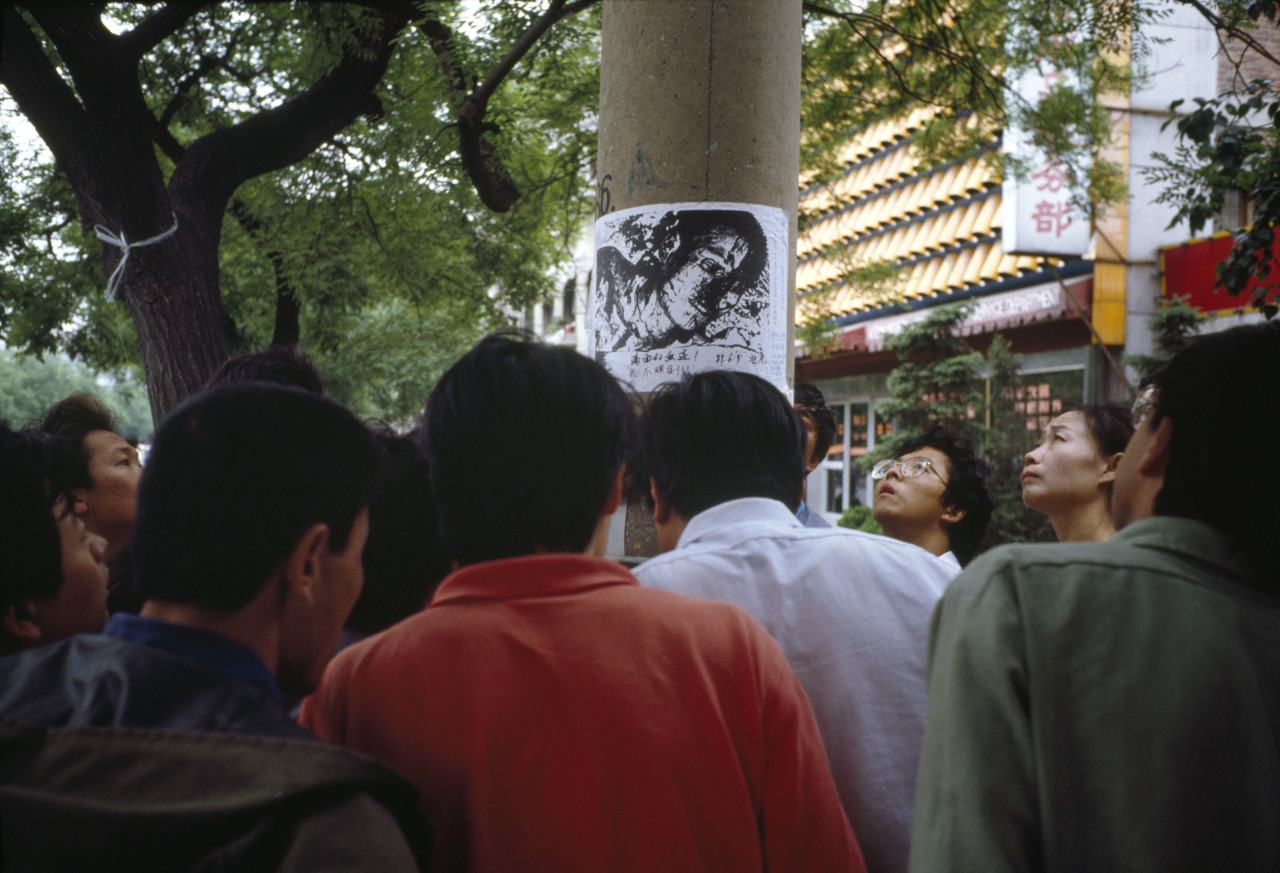

Beginning with this early act of iconoclasm, disrupting the careful iconography of Tiananmen Square, still dominated by the all-seeing celestial eye of the Great Helmsman, the détournement began[4]. Part satire, part revolt, the student protest took many forms over the spring months of 1989. The students wanted Hu Yaobang’s objectives (better treatment for intellectuals and more money for education) realized and his reputation restored by the Party leadership, which was perceived by the student protesters to be a corrupt gerontocracy.

The reaction of the Chinese leadership to the protesters darkened by degrees. On 26 April a front-page editorial in the People’s Daily used pejorative language to describe the protest, accusing a small group of rabble-rousers of seeking to undermine the regime. At 10 a.m. on 30 May—the very morning that the Goddess of Democracy statue was erected—martial law was declared. Demonstrations were banned (Suettinger 2003[5]). The press, including the foreign media, was proscribed and prevented from using satellite uplinks in China.

On 2 June troops descended on Greater Beijing where the People’s Liberation Army strength reached more than 180,000 (Suettinger 2003). After the massacre to the west of the Tiananmen Square, 10,000 troops surrounded about three thousand demonstrators who had not yet left the square (Richelson and Evans 1999[6]).

In the final assault the PLA established control over the square more by intimidation than mass slaughter, although there were many casualties during advances in the early hours of 4 June (Gittings 2005,[7]). Most of the killing had already taken place in other parts of Beijing by 4 a.m., the time the lights in the square were switched off, and the protestors decided to leave the square (ibid.).

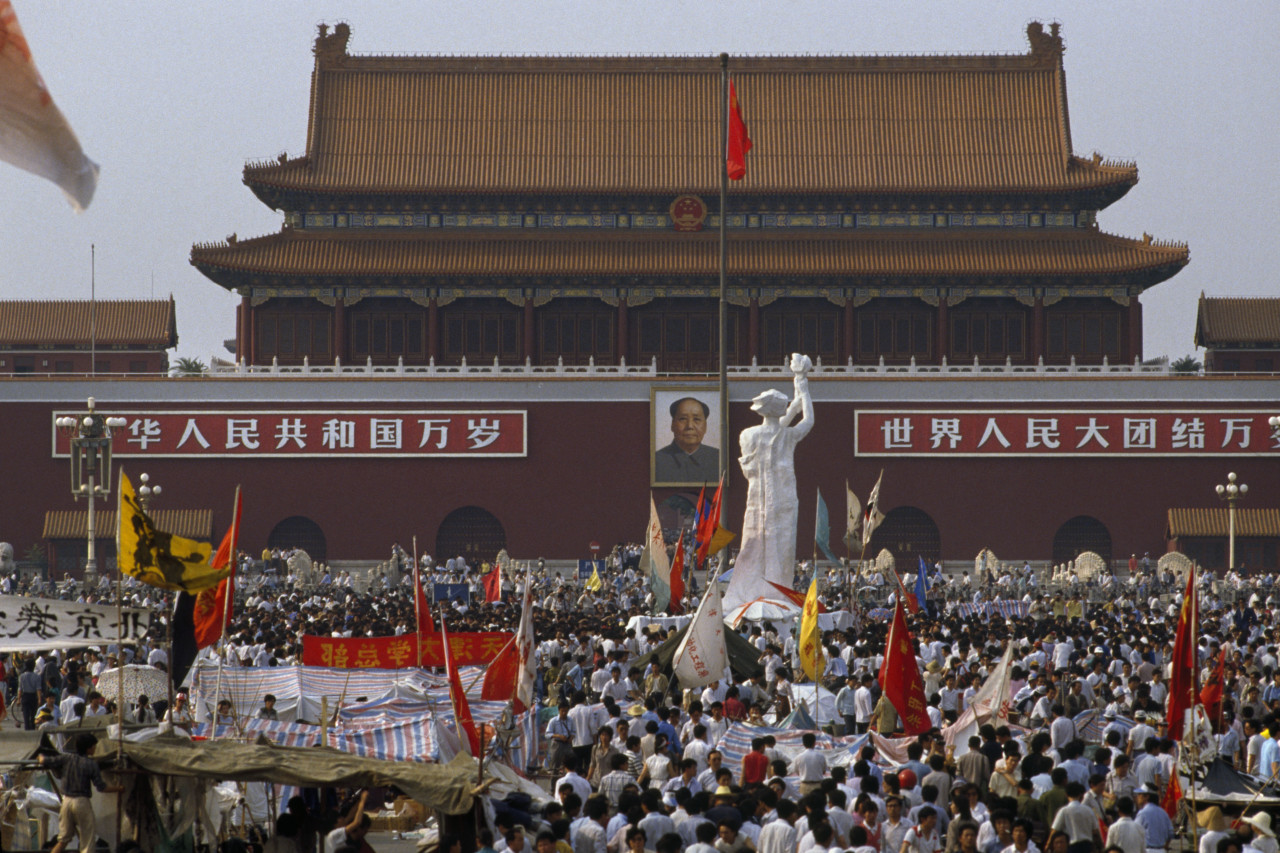

Before the massacre the mood during the occupation of Tiananmen Square ranged from heady optimism to desperation. Political street theater, in situationist style, led the approach to challenging the state (Esherick and Wasserstrom 1994[8]). This took several forms, including a solemn presentation of a petition on the steps of the Great Hall of the People, to a partially observed hunger strike (Pomfret 2006[9]; Wong 1996[10]). The placement of the Goddess of Democracy statue in Tiananmen Square—“directly between two sacred symbols of the Communist regime, a giant portrait of Mao and the Monument to the People’s Heroes was another powerful piece of theatre” (Esherick and Wasserstrom 1994).

The Goddess of Democracy

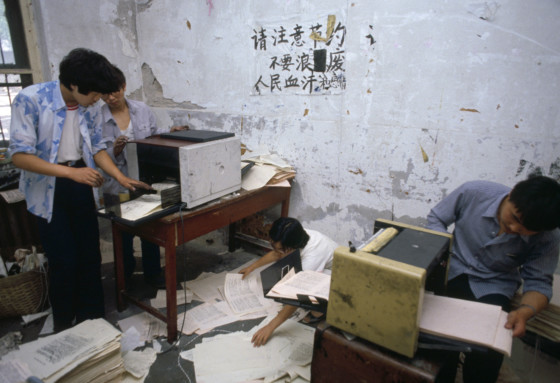

In the courtyard below the dormitories of China’s leading art school, where peasants once learned to copy approved portraits of Chairman Mao, a noisy new venture kept any light sleepers awake: the round the-clock building of the Goddess of Democracy. Construction began on 27 May. The design was based on a renowned Soviet sculpture by Vera Mukhina: A Worker and Collective Farm Woman.[11]Fifteen students built the ten-meter high Styrofoam statue in just three days (Tsing-yuan 1992[12]).

As dawn broke on the clear morning of 30 May the Goddess of Democracy became “a direct challenge to the state’s monopoly over the iconography of the Square” (Hershkovitz 1993[13]). Facing the 6 × 4.6 meter portrait of Mao hanging on Tiananmen Gate, the “goddess” became both “an explicit challenge to the state’s power to define and control political space” (ibid.) and a challenge to the inherent sacredness of China’s national emblem[14]adding a sixth monument to the Square.

The statue galvanized support for the protest movement at a time when it was flagging. To no one’s surprise, “[T]he offcial media exploded in an orgy of condemnation” (Suettinger 2003). “Tragically”, wrote Robert Suettinger, a seasoned analyst, “the symbol of students’ hopes was probably the last straw for the government. Any chance of averting a violent showdown was now gone” (ibid.). Four days later the Goddess of Democracy was gone, demolished by an armored personnel carrier (APC) or a tank (accounts vary), just after dawn on 4 June (Lim 2014[15]; Wong 1996), its life a little shorter than that of the average butterfy, its impact as devastating as a plague.

Tank Man

Following the downfall of the Goddess of Democracy, early on 4 June 1989, Tiananmen Square was cleared of civilians and debris by the PLA. However, a group of civilians, some relatives of the students, lined up to face a double row of soldiers who stood or knelt in firing positions with a column of tanks and the debris of Tiananmen Square behind them. According to a wide range of accounts, including this author’s, these civilians were shot at repeatedly, leaving at least twenty casualties.[16]As the bodies were carried away on trishaws, the standoff died down and a column of tanks broke through, moving slowly east along Chang’an Avenue.

Waiting for them, a few hundred meters down the road, and directly opposite the Beijing Hotel, stood a man in a white shirt and dark trousers, holding two shopping bags. Alone he blocked the path of the tanks, watched by groups of nervous bystanders, and perhaps fifty journalists, camera crews, and photographers occupying balconies on almost every floor of the Beijing Hotel. The press members were prevented from leaving the premises by the Public Security Bureau.

I was lying prone on a balcony on the sixth floor with Newsweek photographer Charlie Cole photographing the event around noon on that day, which I remember was 4 June.[17]On the balcony after the event, which lasted less than three minutes, a conversation ensued with a writer for Vanity Fair, T. D. Allman. Allman insisted (correctly as it turned out) on the significance of the spectacle. I recalled images from 1968 in Prague and Bratislava where protesters stood up bare-chested against Russian tanks. Tank Man felt very distant by comparison. The photographs I had taken, as seen through the lens, appeared to lack the impact of, for example, Josef Koudelka’s images from Prague. My photographs were smuggled out of China the following day,[18]and the transparencies were later processed, duplicated, and distributed from Magnum’s offices in Paris.[19]

Images and reporting of the tank man incident emerged slowly. Although pictures from the earlier standoff were published on 5 June,[20] I traced only one reference to a man confronting a tank that was published on that day (and therefore referring to an event on 4 June). This was in the British Daily Mail, attributed to their Beijing correspondent:

Standing with my husband at our apartment window high over Changan Avenue early yesterday I watched a tank speeding towards the heart of Peking. As it rumbled on, surrounded by a tangled mass of bicycles, that brave man moved out to bar its progress, a lone symbol of the people power that had gripped China. The war machine never slowed, even for a moment. Its tracks enveloped the man as it rushed onwards to complete its mission. That tank was the frst of many that came rumbling down the Avenue of Eternal Tranquility and into Tiananmen Square to slaughter unarmed teenagers, that one death the beginning of an orgy of violence. (Roberts 1989, 21)

In the report “that brave man” was either another less fortunate person defying a tank or, more likely, the same person misdescribed.[22]

Apart from this lone report, the first the world saw of tank man was on television on 5 June. Television coverage spurred interest in the incident. George Bush referenced it after watching CNN.[23]“I was very moved today,” Bush intoned at a news conference on the morning of 5 June, “by the bravery of that one young individual that stood alone in front of the tanks, rolling down, rolling down the avenue there” (Permutter 1998[24]). The television images were shot by, among others, Jonathan Shaer (CNN) and a cameraman for French Antenne 2 (now TV2), whose film was reportedly later seized.[25]

The CNN footage, smuggled out of China on 4 June, was first downlinked from Hong Kong’s Media Centre late on 4 June or early 5 June local time.[26]Reportedly, other US and European networks recorded and broadcast the CNN satellite feed.[27]CNN’s Tom Mintier narrated the story of the tank man’s ballad from a landline in Beijing: “[T]he world witnessed a daring act by one man against insurmountable odds. Armed with only courage, standing in the middle of the street facing more than a dozen tanks bearing down on him, he refused to move. He demonstrated the will to resist beyond any words that could ever be spoken” (Permutter 1998). NBC began its report with George Bush’s statement.

Suddenly, photographs that had held virtually no interest the previous day, became iconic—yet only where television had broadcast the incident.[28]Tank Man became a symbol of courage and also a symbol of freedom in the face of a totalitarian state, and ultimately an icon reinforcing its neoliberal connotations. Given the impact of the television footage, it was no accident, then, that the only newspapers that featured the Tank Man photograph prominently on the front page on 6 June were those published in countries with widespread television coverage of the event featuring their national on-the spot reporters: for example, in France (Figaro and Libération), Italy (Corriere della Sera), the United States (New York Times, Los Angeles Times, St Louis Post-Dispatch), and Britain (Daily Mirror, Daily Express, The Times, and Daily Telegraph).[29]It should also be noted that in those countries as many newspapers chose not to publish the Tank Man at all, but instead used images of the earlier standoff, described above, for the front page.[30]As Andrew Higgins, a reporter for the British newspaper The Independentbased at the Beijing Hotel, commented, “I did not see tank man so did not report his effort to stop the tanks. [I] heard about him later—and he seemed far less significant than all the people getting shot.”[31]

Internationally, two entirely different photographs featured more prominently. On 5 June a photograph by an anonymous Chinese photographer came to light. It depicted a scene where eleven people were crushed to death by a single army APC in the Liubukou district (Gittings 2005). On 6 June, pictures appeared globally of the 4 June standoff between the PLA and civilians on Chang’an Avenue (based on a survey of twenty-five international newspapers). Both these photographs described and expressed the massacre of Chinese civilians.

During 1989 the Tank Man photograph became more iconic in the West, but almost unrecognizable in China. Here was a modern-day version of David and Goliath, or of Horatius saving Rome, a symbol of courage—a super-icon, or “the icon of the revolution” as The Guardian described it on 4 June 1992. Time magazine named the “unknown rebel” Man of the Year (Iyer 1998[32]): a man, and an image, “like a monument in a vast public square created by television” (Gordon 1999[33]).

In one study of the Franklin image the authors considered that the Tank Man photograph diverted the rhetoric on Tiananmen: “As the image of the man and the tank achieved iconic status it has acquired the ability to structure collective memory, advance an ideology, and organize or direct resources for political action” (Hariman and Lucaites 2007). The photograph has gradually become metonymic for Tiananmen, overwriting the images that were so compelling at the time and that spoke to the massacre that had occurred. Why would this be so? Or, as one commentator has asked, “Why are Westerners so fascinated by this image? Is it because it fits so nicely with the story we expect to see—good against evil, young against old, freedom against totalitarianism?”

Notes

[1]Hariman, R., and J. L. Lucaites. 2007. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

[2]Scobell, A., and L. M. Wortzel, eds. 2005. Chinese National Security: DecisionMaking Under Stress. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute and Army War College.

[3]Wu, Hung. 1991. “Tiananmen Square: A Political History of Monuments.” Representations 35 (Summer): 84–117

[4]The term détournement derives in substance from the situationist political happenings led by Guy Debord during the student uprising in Paris in 1968 (see Debord 1983). It should also be noted that the protest movement began before Hu Yaobang’s death (Scobell and Wortzel 2005, 70).

[5]Suettinger, R. L. 2003. Beyond Tiananmen: The Politics of U.S.—China Relations, 1989–2000. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute.

[6]Richelson, J., and M. Evans, eds. 1999. Tiananmen Square 1999: The Declassifed History. Washington, DC: National Security Archive Electronic Briefng Book No. 16.

[7]Gittings, J. 1989. “Liberty Goddess Riles Leadership.” The Guardian, 31 May, p. 10.

[8]Esherick, J., and J. Wasserstrom. 1994. “Acting Out Democracy: Political Theater in Modern China.” In Popular Protest and Political Culture in Modern China, edited by J. Wasserstrom and E. Perry. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

[9]Pomfret, J. 2006. Chinese Lessons: Five Classmates and Their Story of New China. New York: Henry Holt.

[10]Wong, J. 1996. Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now. Toronto: Doubleday

[11]Photographs of the sculpture appeared on Soviet postage stamps and were included in the Soviet Calendar 1917–1947, a compilation of Soviet propaganda published to mark the revolution’s fortieth anniversary. The sculpture was originally placed atop the Soviet Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World Fair. The head of the farm worker was the principal inspiration for the face and head of the Goddess (Han Minzhu 1990).

[12]Tsing-yuan, T. 1992. “The Birth of the Goddess of Democracy.” In Popular Protest and Political Culture in Modern China, edited by J. Wasserstrom and E. Perry. Boulder, CO: Westview Press

[13]Hershkovitz, L. 1993. “Tiananmen Square and the Politics of Place.” Political Geography 12, no. 5: 395–420

[14]Tiananmen Square appears on all government seals and other offcial materials: “The gate became an emblem, its image replicated in isolation on banknotes and coins, on the front page of all government documents, and in the nation’s insignia” (Hung 1991, 88).

[15]The journalist Louisa Lim recently showed the Tank Man photograph to 100 Beijing university students. Only ffteen recognized the picture (Lim 2014, 86). In China the image has been wilfully airbrushed from history.

[16]See, for example, Andrew Higgins (1989), Catherine Sampson (1989), Jan Wong (1996), and South China Morning Post (5 June 1989, 1 and 3). In this unattributed account thirty people were reported to have died. Confrmed in Document 32 declassifed SITREP from the US Embassy’s chronology: “4th June 10.25-12.10 -four separate incidents of indiscriminate fre on crowds in front of Beijing Hotel. At least 56 civilian casualties” (NSA Archive, http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/ NSAEBB16/docs/doc32.pdf).

[17]There is still controversy over the date of this event. I made my position on the date clear in Kristen Lubben’s (2011) Magnum Contacts Sheets while writing on Tiananmen Square. Of about eleven eyewitnesses and fellow travelers who were in Beijing on that day, nine agree that the image was taken on 4 June (listed here with their affliations in June 1989): Andrew Higgins, The Independent; Guy Dinmore, Reuters Beijing Bureau Chief; Arthur Tsang, Reuters; Catherine Sampson, Times (London); Brian Robbins, CNN; Jonathan Shaer, CNN; Fred Scott, BBC; Eric Thirer, BBC; and Charlie Cole, Newsweek. Chinese academic Wu Hung also confrms the date of 4 June (2005, 14), as does Mike Chinoy’s 2014 flm On Assignment: China.

[18]The rolls of flm were packed into a small box of tea and taken to Paris by a French student.

[19]Magnum Photos was founded in 1947 and today has offces in Paris, London, New York, and Tokyo.

[20]For example, see New Straits Times (Singapore) 5 June 1989, 3. The same paper reported on page 1 that ten tanks and sixteen APCs left Tiananmen Square to travel east along Chang’an Avenue, 3 km toward the embassy district and then returned.

[21]Roberts, M. 1989. “Tackling Tanks with Sticks.” Daily Mail, 5 June, pp. 2–3. Sampson, C. 1989. “Bravery, Hatred and Ongoing Carnage.” Times (London), 6 June, p. 1.

[22]At a press conference on 4 June 1990 student leader Chai Ling claimed she knew of a young woman who, on the evening of 3 June, stood in front of a tank and was crushed to death (Permutter 1998, 62).

[23]http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/mediaplay.php?id=17103&admin=41. Presidential News Conference on 5 June 1989. The word “democracy” in relation to China is mentioned countless times, for example, “People are heroic when it comes to their commitment to democratic change.”

[24]Permutter, D. 1996. “Visual Images and Foreign Policy: Picturing China in the American Press 1949–89.” Ph.D. diss., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis and Saint Paul

[25]Charles Cole, email to author, 18 October 2014.

[26]Jonathan Shaer, email to author, October 2014.

[27]Jonathan Shaer, the CNN cameraman who flmed the tank man sequence, claims to be alone in recording with a video camera on a tripod, and therefore to have footage of high quality. Shaer claims that the other US networks were monitoring the satellite feeds, dialed in the correct frequency, and recorded the sequence. There is no encryption. Generally ownership is respected (Shaer, personal communication to author, 2014).

[28]Reuters photographer Arthur Tsang fled an image of tank man climbing onto the tank on 4 June, but it garnered little interest from his superiors (Tsang, personal communication via Charlie Cole, 2014). At the same time CNN transmitted two still images from the video footage from Beijing, but they were not broadcast (ibid.).

[29]It should also be noted that in at least four British national newspapers the Tank Man photograph did not run at all during June 1989: The Guardian, The Independent, The Sun, and the Evening Standard.

[30]Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Sydney Morning Herald, Süddeutche Zeitung, El Pais, and The Independent were some of the national newspapers who chose to run the stand-off between the PLA and civilians rather than the tank man on their front pages on 6 June 1989.

[31]Andrew Higgins, email to the author, 15 October 2014.

[32]Iyer, P. 1998. “The Unknown Rebel.” Time, 13 April, p. 192

[33]Gordon, R. 1999. “One Act, Many Meanings.” Media Studies Journal (China Issue) 13, no. 1: 82–83