Olay, the Debut Photobook by Emin Özmen

Described as his “tribute to the people in Turkey who marched for justice,” Özmen’s first photobook traces 10 years of tumult in his homeland

“When I was eight years old, on a warm July day in 1993, I was holding my mother’s and father’s hands as we waited for a bus near the highway. We were heading back to Sivas, the city where I was born and where we were living,” Özmen writes in the afterword of his debut photobook, Olay, published by MACK this past fall.

“It was a beautiful day, but the atmosphere was heavy. My parents were tense, their faces closed, sad, and silent. They had just learned that the Madımak Hotel in Sivas had been attacked by a mob of radical Islamists after Friday prayer. On that day, thousands of angry people had set fire to the hotel, slashing the fire hoses of the firemen to prevent them from extinguishing the flames that consumed the lives of 37 people trapped inside, mostly Alevi intellectuals and artists. This traumatic event was the first ‘Olay’ — ‘incident’ or ‘event’ — I experienced. The first I can remember.”

It was a moment that left a permanent mark on the photographer, “the beginning of many questions that I began to ask myself about my country,” he explains.

Özmen spent the first 18 years of his life in Sivas, a high-altitude town surrounded by mountains in central Turkey. He speaks of the long, icy winters when he would have to go to school while it was -20 °F for months on end. “The people there are generally irritable — because of the climate, I suppose. But they are also very conservative and ultra-nationalist,” he explains in an interview just after receiving the first copies of his book. “I think that’s the main reason why I’ve always been curious about other places. I always wanted to go and discover everything behind those mountains, which was our only view.”

"On that day, my innocence vanished. It was as if I had to try and understand everything, to document all of it, to feel whatever it was to compensate for the helplessness and disbelief I felt that day. "

-

It was during those early years in Sivas that he discovered the language of photography. For him, the camera became a tool that he felt would allow him to travel to new places, connect with people, and perhaps find answers to the myriad questions triggered that day in July 1993. Ten years after the attack, just after turning 18, Özmen left his home in Sivas. Driven by his insatiable curiosity, he started traveling the country, meeting new people, listening to their stories, and documenting everything along the way.

Olay is the photographer’s first photobook. Through a series of 87 images, the book traces over a decade of his thorough documentation. The story begins in 2013, which Özmen describes as the moment that “everything was turned upside down” for the country. In May of that year, what started as a peaceful sit-in to save Taksim Gezi Park in Istanbul swelled into mass protests around the country in response to intense police violence. “For weeks, I was at the heart of the protests, trying to capture the hope, confusion, unity, and violence of this period that changed modern Turkey,” he writes in the book.

And from then on, the “olays,” or incidents, kept coming. “Military operations, purges, repression, student demonstrations, disrupted elections, barricades, tear gas police operations, detentions, bombings, and funerals followed one after another,” he explains. “Then, earthquakes, floods, forest fires, extreme drought, and an unprecedented economic crisis joined the ballet of tragedies. Meanwhile, massacres in Syria, Iraq, and far away in Afghanistan left millions of refugees to flood into Turkey.”

"Turkey may be one of the few places under the sun where journalists, not to mention locals, pray for less news, not more."

- Piotr Zalewski

Olay is a visual representation of this decade for Özmen — a ceaseless barrage of incident and tragedy, from the nationwide protests in 2013 to the aftermath of two large-scale earthquakes in February 2023. “I tried to record as many of these moments as possible,” he says. “I wanted these events and these people not to be forgotten, so that we can learn from our mistakes, and, I hope, change them.”

"Earthquakes, floods, forest fires, extreme drought, and an unprecedented economic crisis joined the ballet of tragedies. "

-

“Turkey may be one of the few places under the sun where journalists, not to mention locals, pray for less news, not more,” writes Piotr Zalewski, Turkey correspondent for The Economist, in an accompanying essay found at the back of the book. “The country these days is barely able to process one pivotal event or crisis before another takes its place.”

It was only during the pandemic that Özmen had the chance to pause and start looking closely at the work to try to understand what the photographs were telling him. “It was overwhelming, huge,” he says. “All the events, drama, everything … It had all happened in such a short space of time.” Working closely with Cloé Kerhoas, co-editor of the book and historian, they set out to put it all together.

The book opens with an image from Gezi Park in May 2013. A group of protestors, all huddled together, flee from billows of tear gas. The next is from the town of Suruç on the Turkish-Syrian border in 2014, as a group of Kurdish men flee, once again, from tear gas. The perspective has flipped, showing them running toward Özmen’s lens rather than away from it. Although the gas is hidden insidiously from view, the sense of fear and urgency in their eyes is very real.

Further on, we see an image of people standing on a damaged military tank in Ankara the day after a failed coup attempt, with one man cloaked in the Turkish flag. Later, a grieving family is shown after an explosion in a coal mine that killed 301 people in the town of Soma in 2014. Later, a wildfire can be seen raging in the village of Dalaman in 2021. And later, there are protests against the announcement of new municipal elections in Istanbul after Erdogan challenged the opposition’s victory in 2019.

“Nothing is simple here, everything intertwines and collides,” Özmen explains, a feeling that is reflected in the non-chronological visual narrative of the book. “His work evokes exactly this sense of havoc and disorientation, of a country where the march of history has turned into a gallop and a blur,” Zalewski adds in his essay.

"Nothing is simple here, everything intertwines and collides. "

-

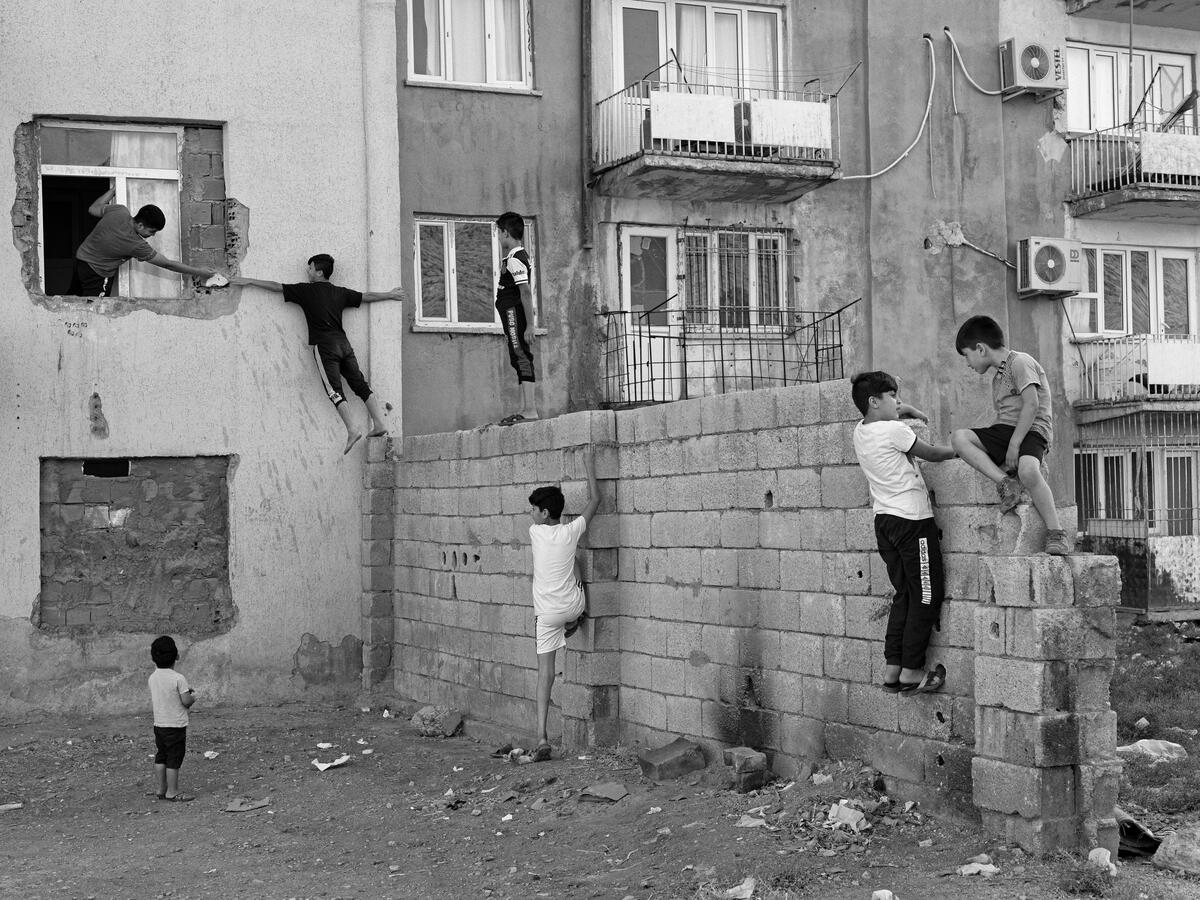

At first glance, the images of the book may seem dominated by violence, fear, and disaster. And yet looking more closely, more carefully, there are glimmers of hope that seem to slip through the cracks, interrupting the cycle of violence with more intimate, or softer images. “Our hearts are heavy, tired, but the resistance prevents us from falling into total despair,” Özmen writes. “We have not forgotten that not only torment, but also grace, wander around us.”

An extract from the poem “Like Kerem” by Nazim Hikmet, a major literary figure and political activist who spent years of his life in prison and in exile, reads:

If I don’t burn

If you don’t burn

If we don’t burn

How will darkness

Ever turn

Into light?

To give readers a framework to understand the body of work, Özmen and Kerhoas have added a timeline of political events and incidents in Turkey since 2013, tracing 10 years of Erdogan’s rule. The addition of the linear historical record helps counterbalance the immersive, non-chronological visual narrative, and with it, Olay becomes an invaluable historical record for the rest of the world—and future generations. “We forget everything very quickly in Turkey, he says. “So the main aim of the book is to contribute to our collective memory.”

"Olay is my tribute to the people of Turkey who marched for justice, to those who wanted nothing more than peace, and who in return were beaten, imprisoned, robbed of their dignity, or died for freedom and equality."

-

“I will probably carry all these painful memories forever,” he says, when asked what the book means to him today. “It was a way for me to bring closure, to put an end to this whirlwind that has left me exhausted and drained. In a very personal way, it’s also a symbol of what my wife Cloé and I went through during those difficult years. We lived through it all together, and putting the book together made us realize just how crazy and sadly remarkable those years were.”

And when asked what is next for the photographer, “I fear the worst for the future … darker days from now,” he says. “But I also know that anything can happen in Turkey, including the best. So I keep a glimmer of hope inside me.”

“In any case, Olay isn’t over, he’s still here, and so am I.”

Olay, published by MACK in fall 2023 is now available here.