Paris Photo 2025: Exploring the Curation

Magnum Gallery melds classic and contemporary in this year's curation, evoking photography's quiet power to leave us wondering, and longing

“Paris Photo is one of the key moments of the year for Magnum Gallery,” writes Clémence Vichard-Larroque, Magnum Gallery’s Senior Gallery Manager. “The city comes alive, drawing in much of the photography world, from artists and collectors to curators, publishers, visitors, and fellow gallerists. It’s a vibrant occasion, a time of discovery, full of meaningful encounters and conversations.”

Each year, Magnum Gallery carefully curates a selection of around 30 fine prints for Paris Photo, bringing together a blend of classic and contemporary from the Magnum archives. This year, the work of 16 photographers have been selected, ranging from a new series by Olivia Arthur to vintage Herbert List prints that date back to the 1930s.

Here, Vichard-Larroque shares her insight into this year’s curation and what to look out for at the Fair.

Paris Photo 2025 runs from November 13–16, with a private view on November 12. Find out more here.

Tell us about this year’s curation and how it came together?

Clémence Vichard-Larroque: Representing both the historic legacy of an agency like Magnum and the contemporary practices of its photographers is a challenging yet captivating task. From 1947 to today, Magnum photographers have been at the forefront of various photographic practices, covering a wide range of subjects, each in their unique way. It feels impossible to encapsulate Magnum’s essence within the approximately 30 pieces we showcase each year at the fair — the most difficult part is narrowing down the selection.

"Our curation plays with silhouettes, half-obscured faces, and shadows"

- Clémence Vichard-Larroque

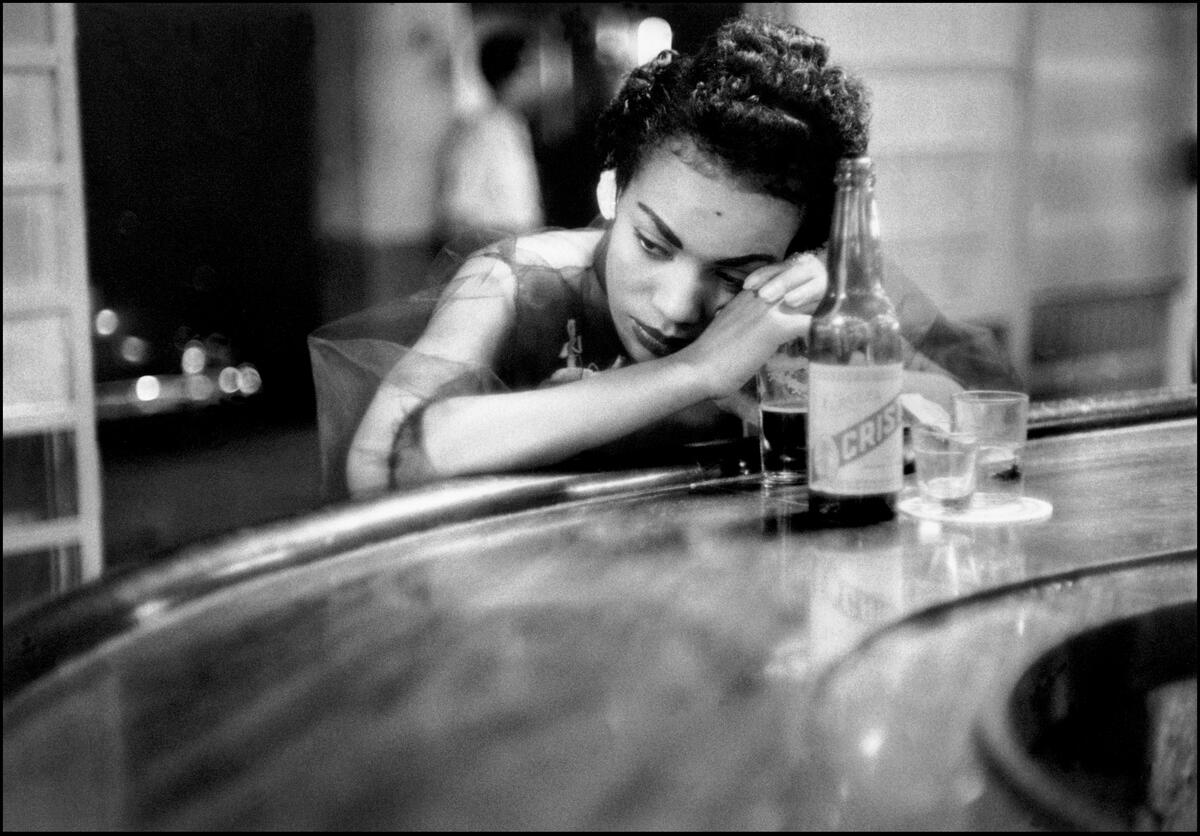

A successful curation for a fair goes beyond strong individual pieces. For our booth, we have several pairings that naturally complement each other, thanks to shared contexts. For example, several photographs by Eve Arnold, René Burri, and Sergio Larrain, were taken in South America during the 1950s and 1960s. We also have works by Raymond Depardon, Susan Meiselas, and Leonard Freed, which all focus on New York City and its inhabitants.

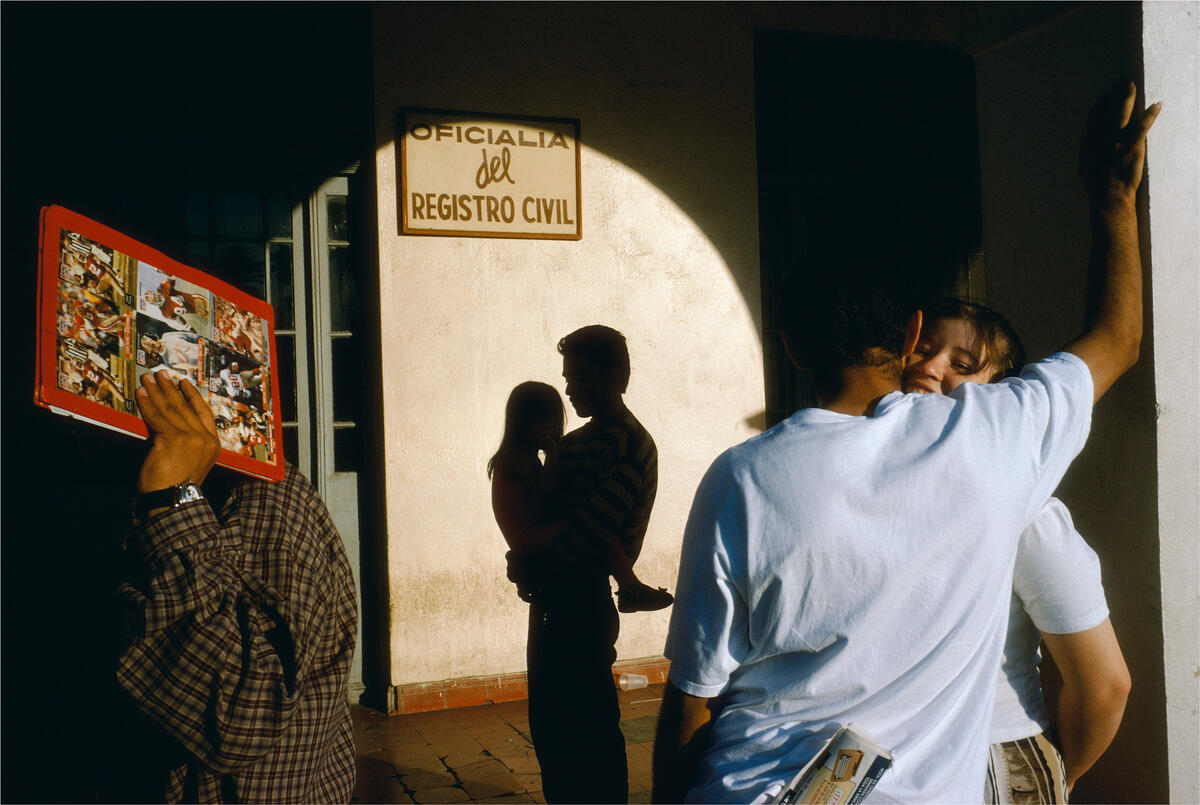

Other pairings, by contrast, lean on visual elements. This year, our curation plays with silhouettes, half-obscured faces, and shadows: motifs that appear throughout most of the photographs featured in our booth. The dark figure walking through Raymond Depardon’s Los Angeles is in dialogue with the deep shadows in Alex Webb’s photograph from Mexico, and echoes the black silhouettes captured by René Burri as they ascend the staircases of 1950s Berlin architecture.

In Harry Gruyaert’s images, faces retreat into shadow, their identities quietly withheld. A rooster slips into Myriam Boulos’ contemporary portrait, masking half the subject’s face, while a laurel branch gently conceals the young man who stood for Herbert List in the 1930s, lending him a timeless anonymity.

This curation favors suggestion over direct revelation. It seeks to highlight photography’s quiet power, its ability to leave us wondering, reaching, and longing for what lies just beyond the frame.

What is new in the curation this year?

This year, we are pleased to present four vintage prints by Paolo Pellegrin. These photographs were taken in Venice in 2005 for a book project commissioned by a German publisher. They are striking for their bold compositions and enigmatic quality. Again, no faces are visible, and deep shadows play a central role. Each print is unique, with only one made of each photograph just after they were captured.

We will also be presenting a beautiful portfolio of Prince Street Girls by Susan Meiselas. The portfolio includes 12 signed gelatin silver prints, three of which are framed and will be on display at the booth. This series explores the passage from girlhood to adolescence, captured in a way that breaks from the artistic conventions of the male gaze. It is also a story of serendipity, of how chance encounters can shape one’s path, particularly that of an artist. For Susan Meiselas, it all began with a group of bored children playing with a mirror, reflecting sunlight into her eyes, a fleeting moment that would lead to one of the most significant bodies of work in her career.

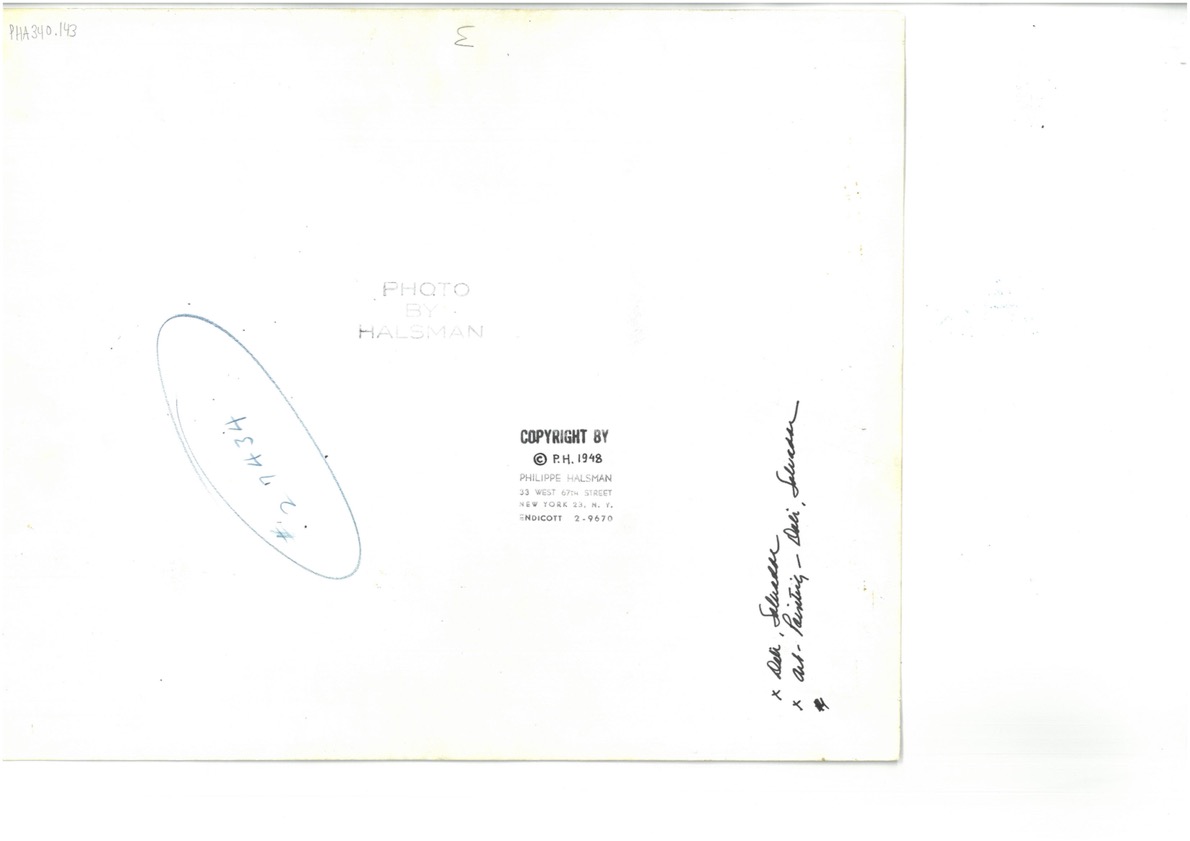

What about the Halsman print of Salvador Dalí? Can you tell us the story behind this print?

Philippe Halsman and Salvador Dalí first met amid the vibrant Surrealist circles of 1930s Paris, where Halsman, newly arrived and endlessly curious, crossed paths with Dalí and other visionaries of the movement. Years later, in the late 1940s, their friendship evolved into a series of creative experiments that blurred the boundaries between photography and performance. The Dalí Atomicus images, as they are now known, stand as the most iconic result of their collaboration.

This project transformed what might have been simple portraits into moments of suspended chaos. Inspired by Dalí’s own painting Leda Atomica (1949), visible in the corner of the composition, everything in the image appears to float in perfect defiance of gravity: the easel, the chair, a stepstool, splashes of water, leaping cats, and Dalí himself.

"[Halsman] was far from a prolific printer, making this a particularly rare and precious piece."

- Clémence Vichard-Larroque

Throughout his career, Halsman photographed many of the most celebrated figures of the 20th century: artists, movie stars, and world leaders alike. His portraits, filled with warmth and wit, reveal not only technical mastery but also his rare gift for making his subjects feel at ease in front of the lens.

This series had a profound impact on Halsman’s career, inspiring him to ask later sitters to jump for the camera, a practice he called “jumpology.” As he explained: “When you ask a person to jump, his attention is mostly directed toward the act of jumping, and the mask falls, so that the real person appears.”

This particular print was made by Halsman himself, close to the time the photograph was taken. During his lifetime, he was far from a prolific printer, making this a particularly rare and precious piece.

What are your personal highlights?

I’m particularly fond of this still life by Harry Gruyaert, taken in a Parisian café in 1985. What stands out to me is the simplicity of the food display in the window, so modest compared to the abundance of sandwiches and desserts we would see today. It speaks to another era, perhaps with a hint of nostalgia. The carefully arranged bowl of fruits, combined with the warm, vivid tones, gives the photograph a painterly quality. For a brief moment, it recalls the quiet elegance of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s still lifes, reimagined here in a more contemporary setting.

Another print on display carries an unmistakable painterly quality. This picnic scene, captured by Herbert List, is often compared to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Sur les bords de la Marne, captured only a few years later. While the two photographs share some aesthetic qualities and a similar subject, List’s image seems to belong to an entirely different era. It feels as though we are gazing into the 19th century, witnessing a timeless afternoon by the Baltic Sea. The composition recalls Georges Seurat’s Un Dimanche après-midi à l’île de la Grande Jatte, as if List and the painter had observed the same figures, their hats and umbrellas shielding them beneath the same gentle sun.