Leopard Print: Through the Magnum Archive

Rosalind Jana looks at the patern's fluctuating fortunes through the lenses of Magnum photographers

In the second installment of a new series delving into the Magnum archive, exploring its decades of documentation of vernacular style around the world, fashion writer Rosalind Jana turns her eye to leopard print – a pattern that has over centuries fluctuated between being an indicator of status and wealth, a high-fashion favourite, a countercultural staple, and has also at times become a token of tawdriness. Here, Jana explores leopard print through the work of Magnum photographers.

You can read Jana’s previous exploration of denim, on Magnum, here.

A woman stands still on a pavement of long shadows, the camera catching her from behind. She is cut off from the waist down, drawing attention to her bright red heels. They’re slingbacks, the strap cutting across the back of her stockings just beneath the ankle. Her handbag is the same shiny, tomato-ish shade: both items echoed in the scarlet skirt of someone else lingering nearby. Another figure in neutral grey tweed and black leather shoes on the right provides a restrained foil to these flashes of colour. However, much as the red initially catches the eye, it’s the print on the central woman’s garment – is it a dress, skirt, or coat? – that really makes the image. It’s leopard.

Harry Gruyaert’s photo taken in Belgium in 1981, forming part of a larger project capturing the Edward Hopper-esque colours of his home country after a long period of absence, is strangely compelling. This trio of women remain mysterious to the viewer, reduced to hems and heels. We can try to piece together the few sartorial clues on offer. But in the case of our central woman, what does her choice of leopard print suggest? At first glance, it seems bold – a suggestive second skin, clashing with those fiery accessories. But the length is rather sensible, reaching down well below the knee. Without access to the wearer’s face or age or context, it’s hard to gauge the overall effect. Is it a bit brassy, or archly elegant, or just quite playful? Does it signify the provocations of ‘bad taste’ or the class connotations of wealth and sophistication?

The questions that can be asked of Gruyaert’s photo also seem apt when considering leopard print more generally. ‘Leopard print’ is a bit of a catch all term, often including the markings – called rosettes – found on other big cats including cheetahs and jaguars. Whichever animal it’s copying, however, it remains a print that’s accrued a vast range of meanings over its history, ranging from the deeply tacky to fustily refined. Spanning bad mothers, grand dames, Halloween costumes, Hollywood mavens, punks, burlesque dancers, first ladies and more, it’s a complex and often contradictory pattern. One that has become immensely popular again recently, with designers from Burberry to Versace returning to its wild appeal over the last few years – in turn spawning a hundred and one different leopard skin midi skirts available on the high street.

"Leopard fur has long been valued: pictured in ancient iconography cladding deities including Greek God of a booze-fuelled good time Dionysus, and formidable Egyptian Goddess of writing and knowledge Seshat"

-

Of course its origins lie in the animal kingdom. Leopard fur has long been valued: pictured in ancient iconography cladding deities including Greek God of a booze-fuelled good time Dionysus, and formidable Egyptian Goddess of writing and knowledge Seshat. Leopards, with their sleek elegance and ferocious reputation, offered both the actual trophy status of being hard to kill (a value that would be revisited in the mid twentieth century by the wives of rich men who made hunting their hobby) and the symbolic power of their attendant characteristics. In the countries and continents where leopards lived, their skins possessed a variety of culturally specific meanings ranging from the ritualistic to indicators of rank or standing. In the West as trade and travel routes opened up, they were sporadically favoured by the aristocracy as a signifier of wealth.

"Later Dior would claim that, 'to wear leopard you must have a kind of femininity which is a little bit sophisticated'"

-

However, it was in the twentieth century that leopard prints properly came to the fore: influenced, no doubt, by various 1920s artistic movements that favored (often deeply colonial) approaches to ‘exotic’ faraway lands. Alongside real leopard fur trim, synthetic alternatives employing fabrics including silk, brocade, and chenille featured in the collections of designers including Jean Lanvin, Coco Chanel, and Lucile. Then in Christian Dior’s first famed ‘New Look’ collection of 1947 one model stalked out in a leopard print dress. Dubbed by the designer ‘The Jungle’, it was inspired by his muse Mitzah Bricard’s well-noted taste for the pattern. Later Dior would claim that, “to wear leopard you must have a kind of femininity which is a little bit sophisticated.” Evoking both glamour and a defiant edge of bite, leopard print’s reputation grew (and became a print repeatedly returned to by the Dior label over the years.)

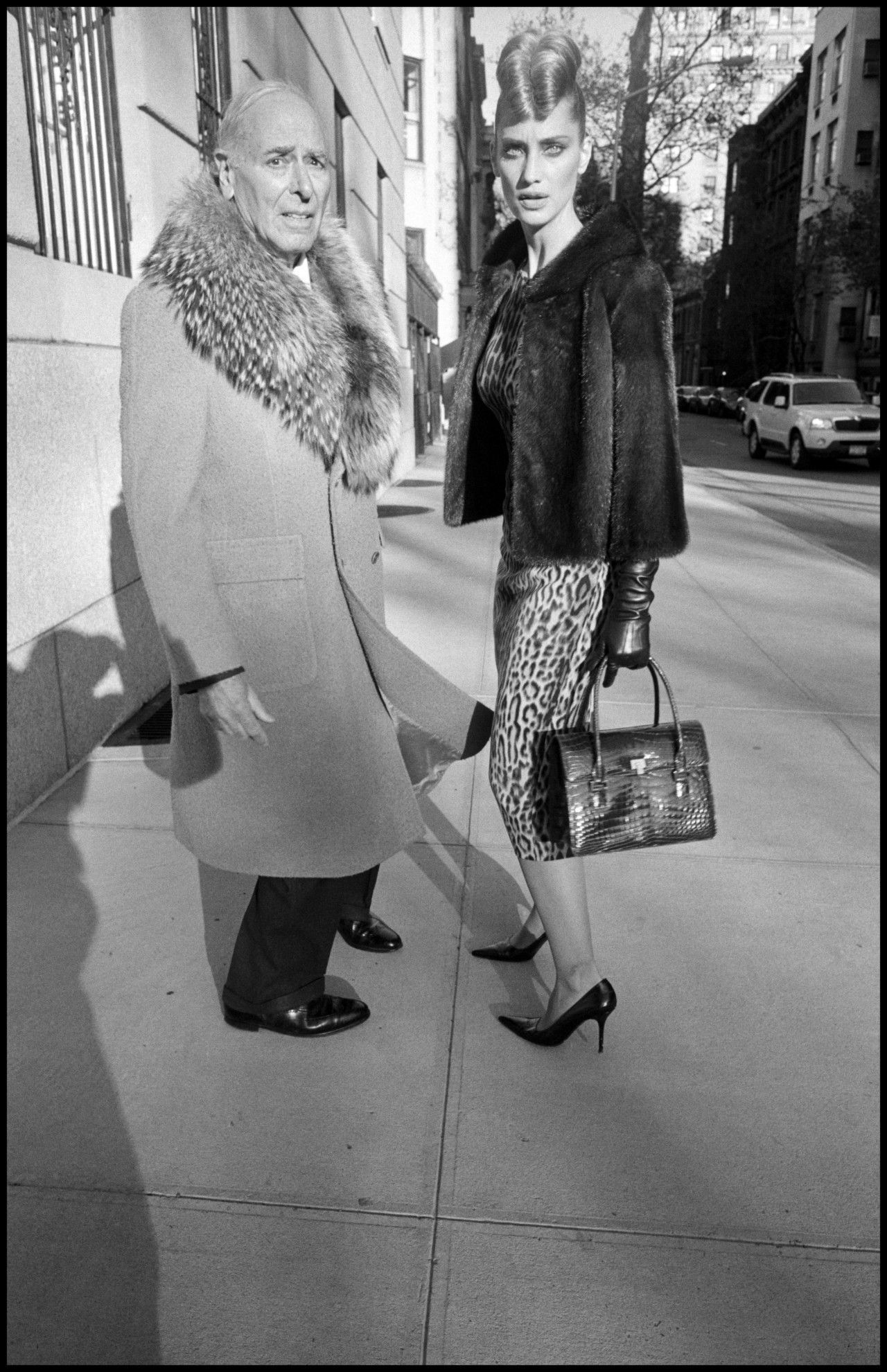

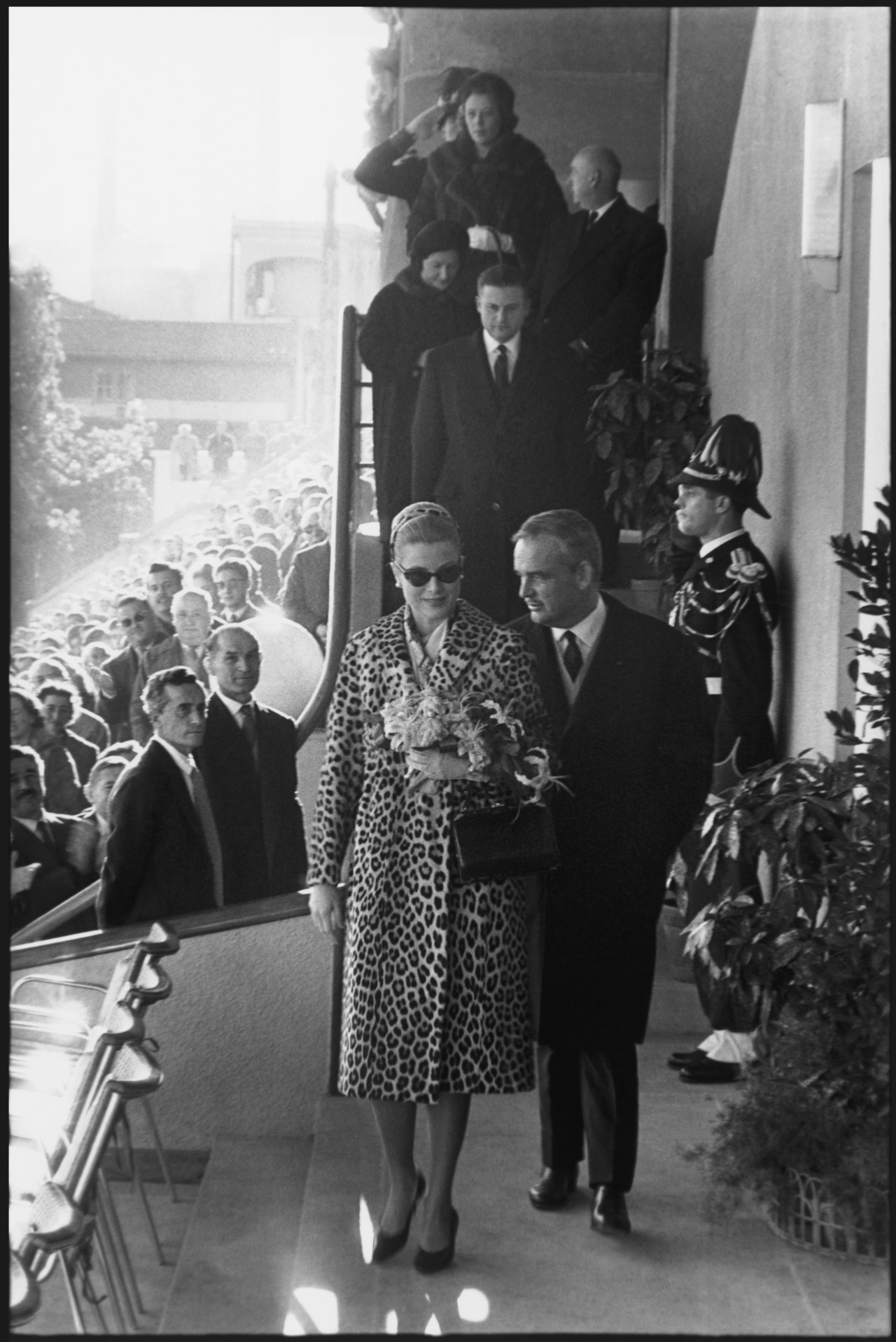

Among the Magnum archives, there are plenty of photos of stately women wearing leopard coats. Sometimes it’s hard to tell whether it’s real, faux fur, or a print. Two women in extravagant headwear stand on a street in Manhattan, one caught with her imposing profile framed by her leopard print hat by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Grace Kelly remains restrainedly chic in Eve Arnold’s 1962 photo showing her attending a football match in leopard and dark glasses with her husband, Prince Rainier of Monaco. In a shot from 1968, Raymond Depardon snaps actress and singer Yvonne Printemps mid-cackle, her leopard print coat matched by a little black veil and pearls. In Guy Le Querrec’s 1980 portrait of singers Lucien Boyer and Parisys, the latter’s leopard print comes with a matching hat, calling to mind previous torch-bearers for co-ordinated headwear and outerwear including Zsa Zsa Gabor and Elizabeth Taylor. These images suggest wealth and glamour, or at the very least mild eccentricity.

"Vanity Fair’s production of leopard print lingerie in the fifties would help cement its status as something both erotic and, ultimately, kitsch"

-

However, there’s evidence too of the way leopard print expanded beyond its initially opulent image to take on other, often clashing values. Vanity Fair’s production of leopard print lingerie in the fifties would help cement its status as something both erotic and, ultimately, kitsch: think pin-ups, performers, fluffy mules, and the kind of underwear that still proliferates today (see Susan Meisalas’ photo of a lingerie store in Brazil from 2014). A leopard print clad Mrs Robinson in The Graduate (1967) would signal a further tilt towards its association with seduction and tawdry thrills.

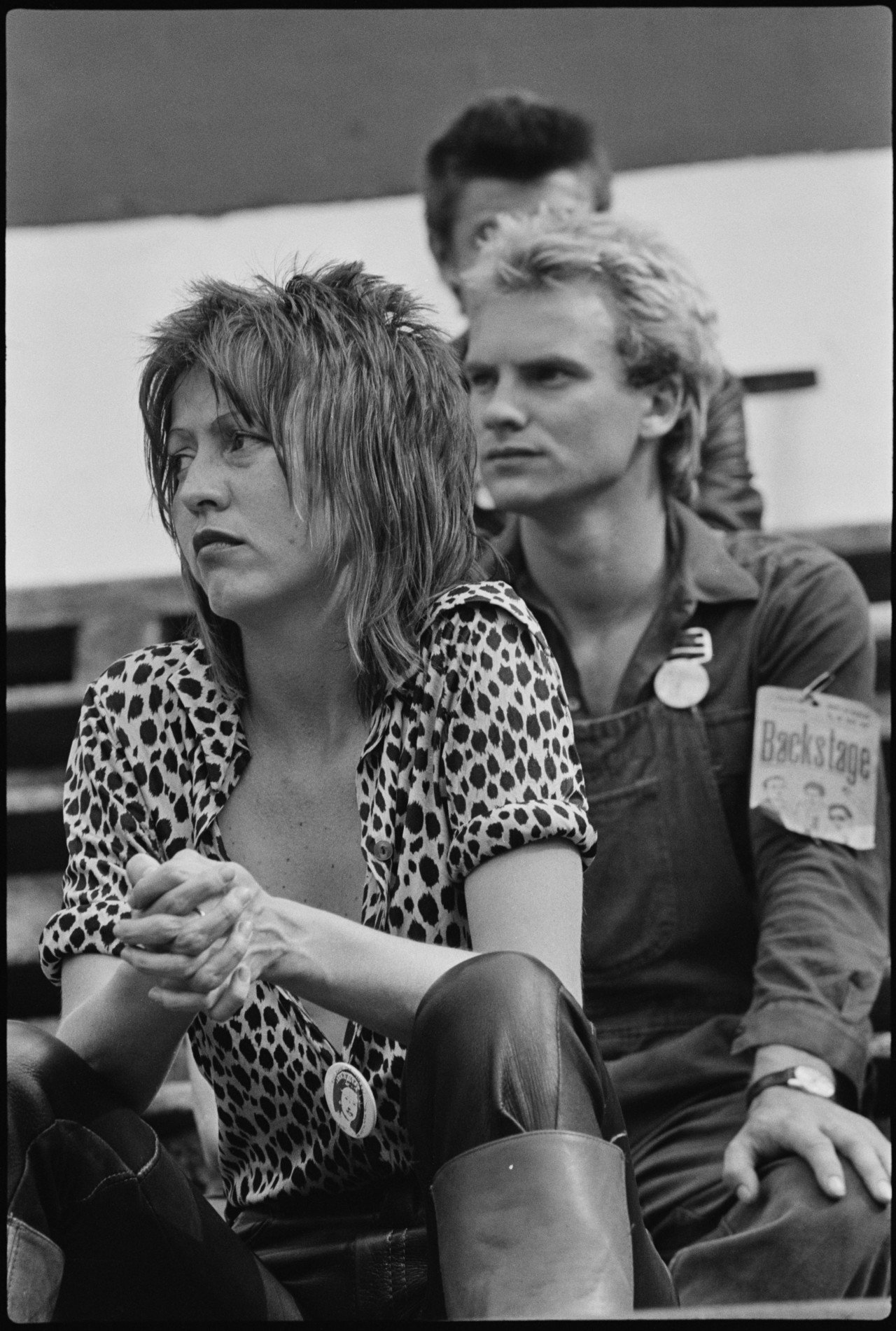

Come the 1970s there was a much-needed ban in the United States on the import of real leopard skins, consumers’ taste for furs having led to declining animal populations. The ensuing decades saw leopard print remaining a high fashion item, but also moving in new directions – particularly into the realms of counterculture. Punks wore it, as per Jean Gaumy’s 1977 photo from a punk rock festival in France featuring wild hair and a shirt left almost open to the waist. They still do too, as evidenced in Martin Parr’s photo from Chile in 2007 of three figures with brightly dyed hair, their leopard print tops and skirts nestled in amongst a profusion of leather, tartan, and studs. Rock and roll women adopted it as well, Debbie Harry most notably.

"From party-wear to high grandeur, from punk to establishment, from pyjamas to ballgowns, it’s clear that leopard print’s appeal is now not just fragmented, but far-reaching"

-

Leopard print’s animal origins have also made for striking – often garish – costuming over the decades. Thomas Hoepker’s 1983 portrait is more of a tableau: grinning, long blonde-plaited hairdresser Francine Hunter taking centre stage as she lounges in her Chelsea loft. Her companions, dressed in tailcoats, doublets, and drapery, look like they’ve been plucked from other eras. Francine, at the front of the shot, is a tongue-in-cheek huntress: clad in a leopard print bustier and thigh high boots on her snakeskin couch. It calls to mind Bruno Barbey’s 2013 Halloween party-goer in a bodysuit and ears and Gueorgui Pinkhassov’s 2017 NYC Pride attendee in skintight red and orange: all very different images and looks, but collectively embodying the potential for leopard print to hover somewhere between the animalistic, the gaudy, and the deliberately sexy.

"[Leopard print] can embody both tackiness and grandeur. It can speak to something feral and free, but can also, ultimately, feel quite tame too"

-

From party-wear to high grandeur, from punk to establishment, from pyjamas to ballgowns, it’s clear that leopard print’s appeal is now not just fragmented, but far-reaching. It can be worn to the office or employed as part of an elaborate dress-up session. It can embody both tackiness and grandeur. It can speak to something feral and free, but can also, ultimately, feel quite tame too.

There’s a further photo from Harry Gruyaert’s explorations of Belgium, this one from 1988. It also features a figure whose face remains invisible to the camera: their leopard print dress spilling out over the person they’re kissing, who has on heeled gold platform shoes, face paint, and blue leg coverings somewhere between spats and leg-warmers. It’s another image that poses innumerable questions about both clothes and wearers. Ones that again remain unanswered. Here the leopard print’s meaning is arguably even more inscrutable. But it definitely looks good: a quick flash of spots in a nightclub, and the suggestion of an (appropriately) wild night.