Behind the Image: René Burri’s São Paulo

In a series exploring the stories behind Magnum Editions prints, we take a closer look at Burri’s photograph of São Paulo in a time of rapid change

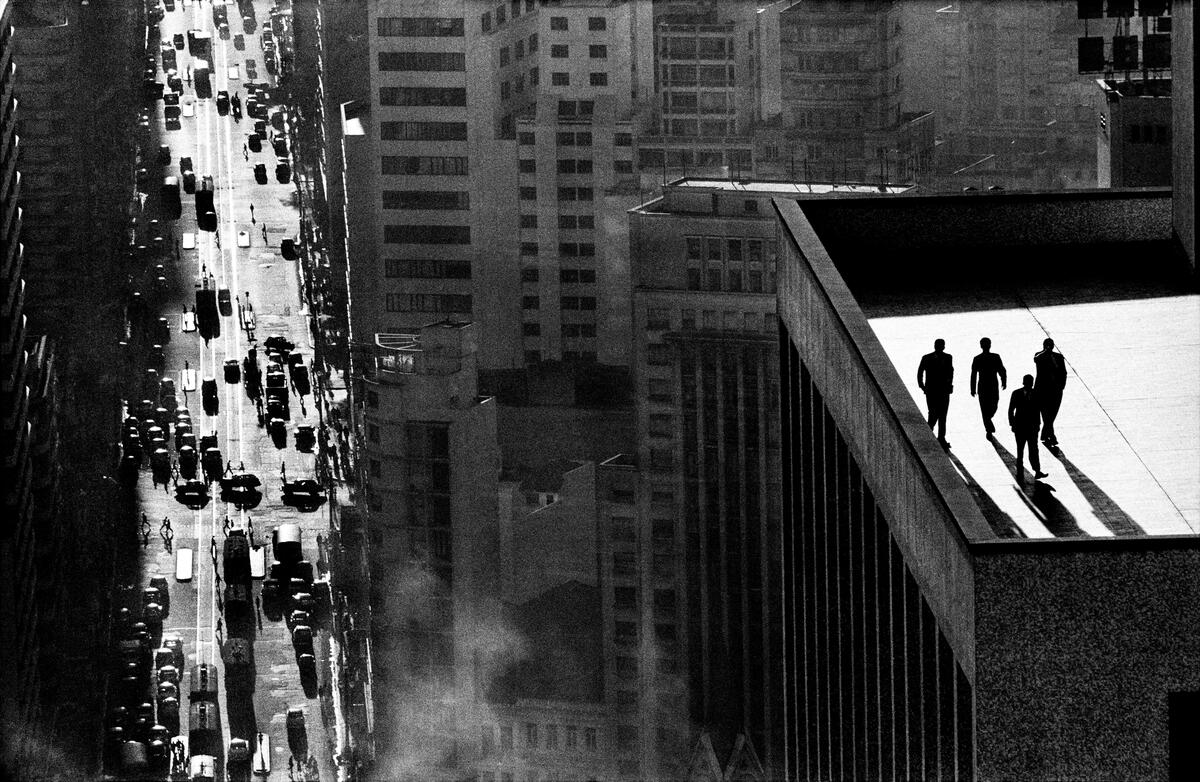

In 1960, René Burri found his way to the top of a sunlit skyscraper along Avenida Paulista, a bustling financial hub in the west of São Paolo, Brazil’s most populated city. He was there on assignment for the German magazine Praline, who had asked him to report on the city and the industrialization of the countryside. The photograph he took from the heights of the southern metropolis became one of Burri’s most recognizable images of his career, coming to represent industry versus human, agency versus precarity.

The featured image above by Burri is now available as part of the Magnum Editions collection, a series of 8×10″ archival pigment prints in limited editions of 100 each. Shop this limited-edition print and explore more Magnum Editions prints here.

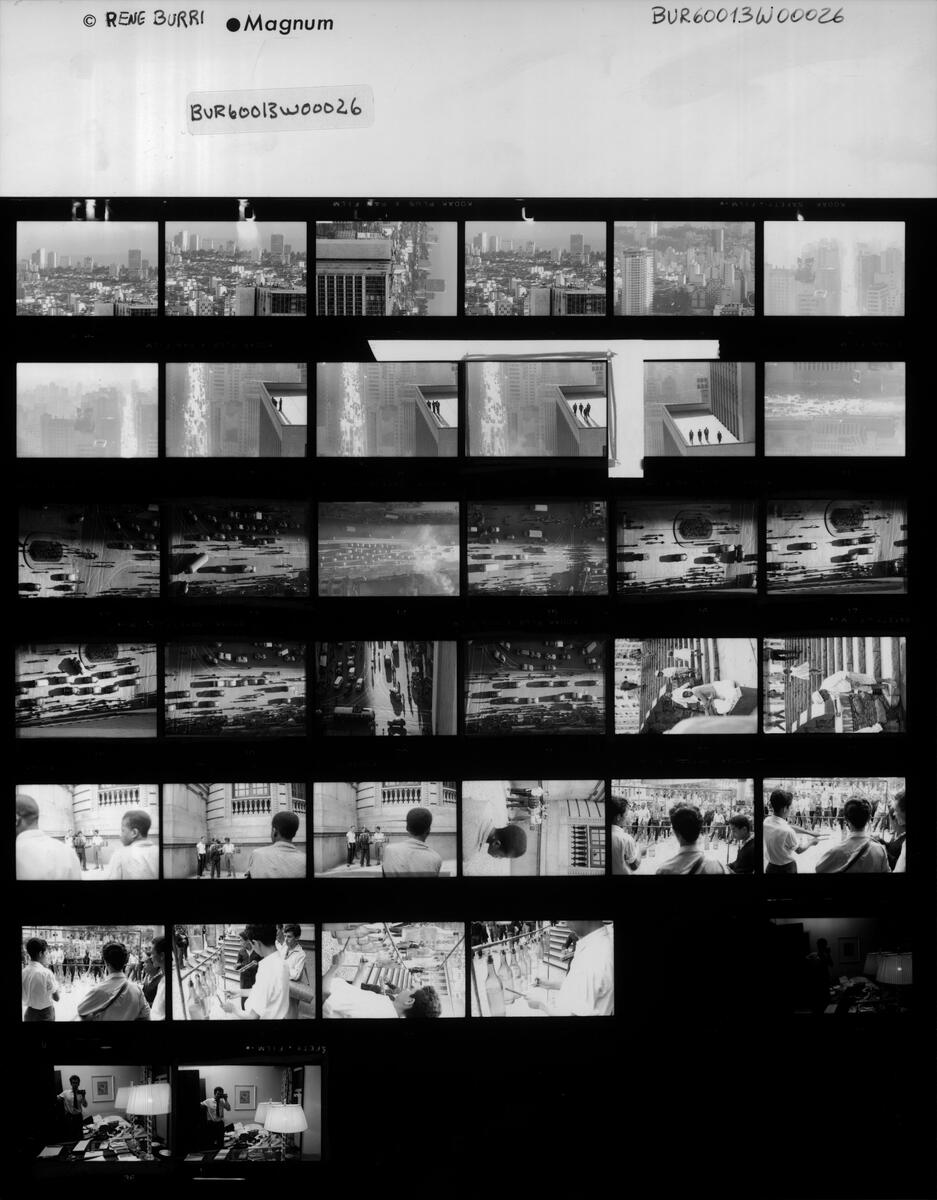

“I climbed around everywhere, I got on the roof of one of the highest buildings,” Burri recalled in the interview “Six Photographs,” directed by Anthony Austin. “At that moment, I looked down — I had a telelens on one of my cameras […] — and I saw these men on the terrace. They came walking, and they just went boom boom boom [pointing gesture with his hand]. They came from somewhere, they went to the edge and looked down, and then they finished.”

Burri’s careful composition guides our gaze towards the men’s sharp silhouettes. “You didn’t know, were they gangsters, were they bankers?” he comments. “And especially this kind of plunge on the left-hand side, right down into the abyss of the mad city.”

Each line, shape and shadow in the image contributes to a dense visual universe, filling the entire frame — a lesson he took from Henri Cartier-Bresson — from the vertiginous ridges of the buildings to the street lines below.

Coupling compositional elements with the human experience allowed Burri to suggest metaphor without being too obvious. Former curator at Musée de l’Elysée, Marc Donnadieu, and assistant curator of the museum’s René Burri Collection, Melanie Betrisey, categorize his São Paulo image as a “double shot,” the first of four “stages” of Burri’s photographic style: “While the viewfinder on the camera imposes a frame on reality that is exterior to it, reality also creates its own frames, with plays of surfaces, foreground and background, rendering it more ambiguous, surprising, and mysterious,” they wrote in René Burri: Explosions of Sight.

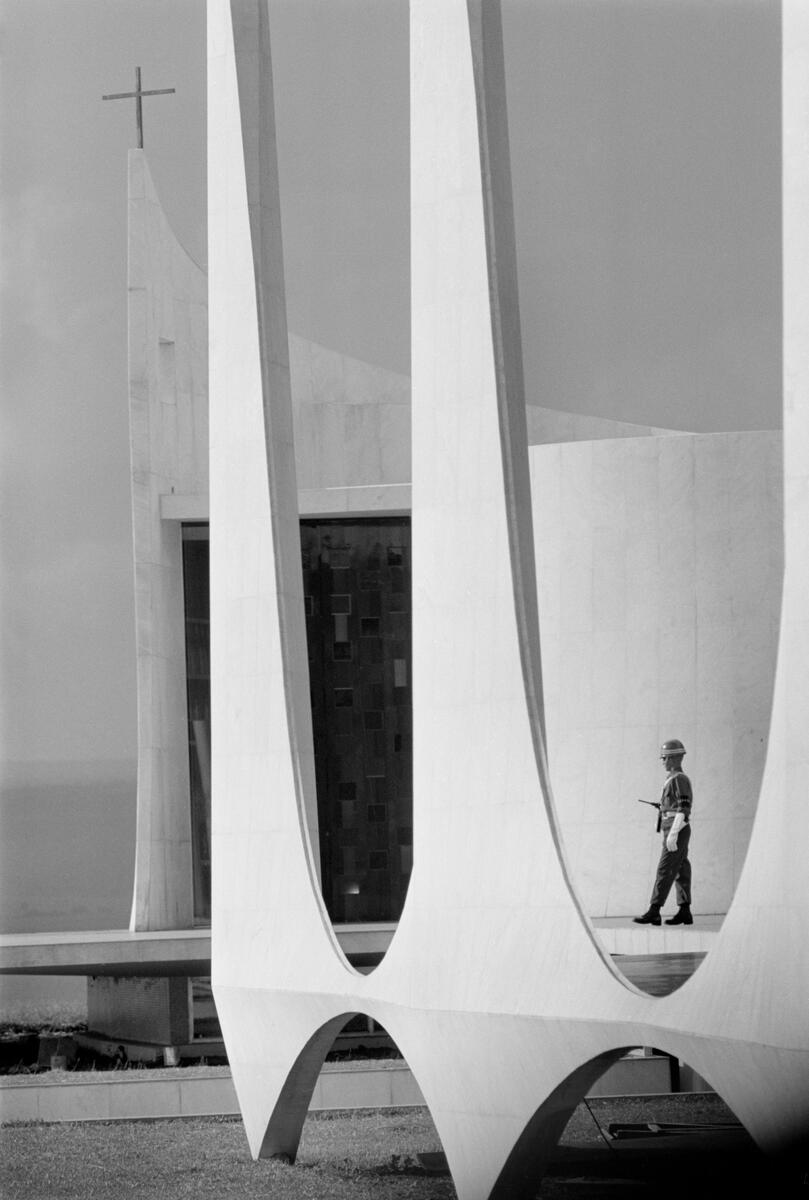

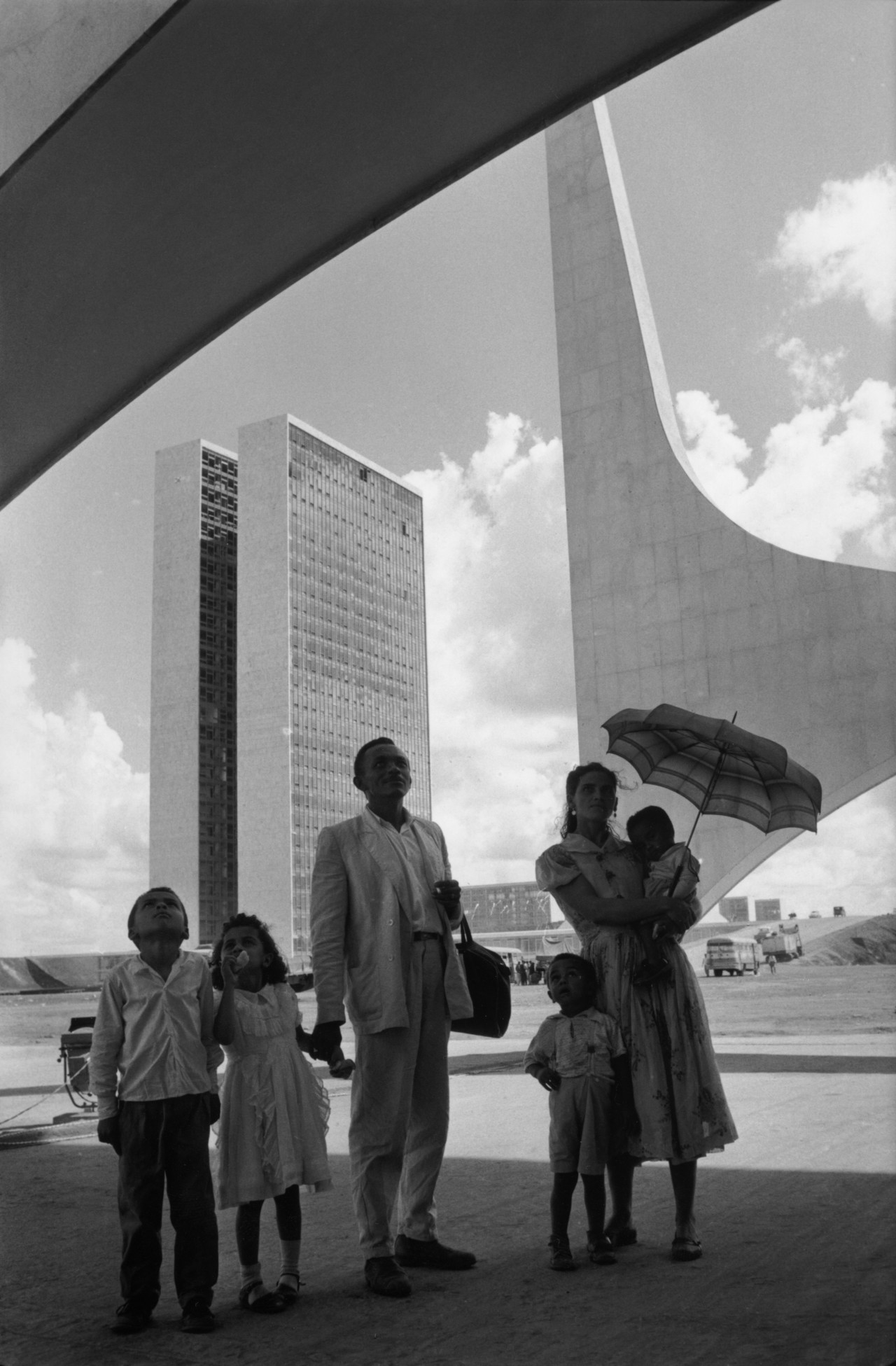

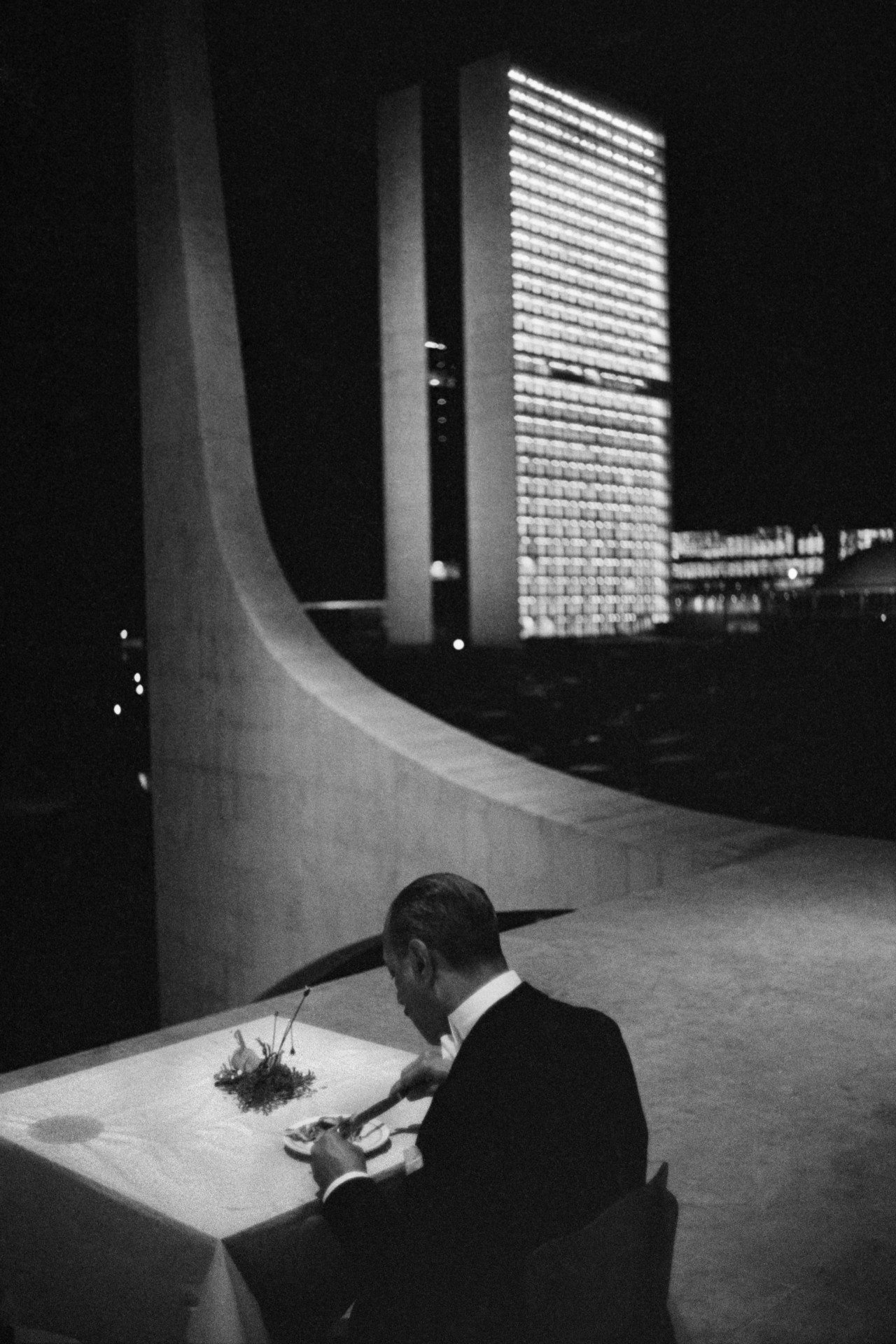

On the same trip, Burri documented Rio de Janeiro and the inauguration of Brasilia as the country’s new capital — Oscar Niemeyer’s freshly erected symbol of modernity. His portfolio from this time shows a nuanced investigation of architecture in a revolutionary era: how did people interact with man-made landscapes as cities rapidly reinvented themselves? Were they empowered, did they adapt? Or did they appear isolated and lonely? Who dominated, and who was ignored?

Burri developed his eye for form during his time at Zurich’s School of Applied Arts from 1949-1953. Hans Finsler, then head of the photography department, was a product of the Weimar movement New Objectivity, which departed from Expressionism and embraced objective realism. Yet Burri was captivated by the emotional resonance in art, particularly in film. “I found myself at the edge of the lake, thinking, ‘this is what I really wanted to show — emotion. But how?’” he said.

Burri’s 1960 images from Brazil, particularly of towering São Paolo, illustrate how he fused this gift for perspective, lines and form with his attention to feeling, his vision of angles and shadows with the human pulse, a signature achievement that seeped deeply into his photographic practice.