The Coles of Tomorrow

An essay by Lindokuhle Sobekwa from “The House of Story,” a publication that brings together the work of four South African photographers, mentored by Sobekwa and Candice Jensen.

“Soon, the Coles of South Africa, living in the democratic South Africa will emerge to demonstrate against that state of affairs.”

— M.W. Serote

What does it mean to rebuild a house fragmented by the past, or to replant a tree uprooted from the ground by structural violence? It will require sizilande, a reclamation of the memory of who we were and the memory of what we will become. It will be a challenging process for Black photographers. What does it mean to pick up the same tool, the camera, used to exploit and explore Black bodies in the past? We have to be careful not to use it in the same way it was used against us, and to find ways to make images that matter. The photographers presented here are defining in their own right what Mark Sealy calls “decolonizing the camera.”

In 1839 photography arrived in Africa and began to be used as a tool to explore and exploit Black bodies. European photographers often had a biased gaze that narrated one-sided stories about African people. To this day some of the images still put Black people at a disadvantage and whites at an advantage. During Apartheid it was difficult as a Black person to be a photographer because the odds were always against you; meanwhile, white photographers had unlimited access to Black townships. They would make photographs in the township and go back to their place of comfort, while the Black photographer documented their own realities that they have to live and answer to every day.

Colonization and Apartheid have uprooted Black people. As writer and thinker Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o put it, “the colonial or any process of domination, the first thing they do is the erasure of the memory of who they are, the memory of the past, and the memory of their being as the people, after erasing that memory, they plant enough memory of the colonizer and the memory of the colonizer becomes the beginning of your memory.” In the 1960s my grandfather left home in the rural Eastern Cape, previously known as Transkei, to go work in the mines in Johannesburg. To this day he has never returned. No one knows what happened to him or if he is still alive. My grandmother remained in the villages. Her children grew up without their fathers. Like many families without fathers our family structures were disrupted. Mothers had to take care of the household alone. To this day many households in Black townships are headed by single mothers.

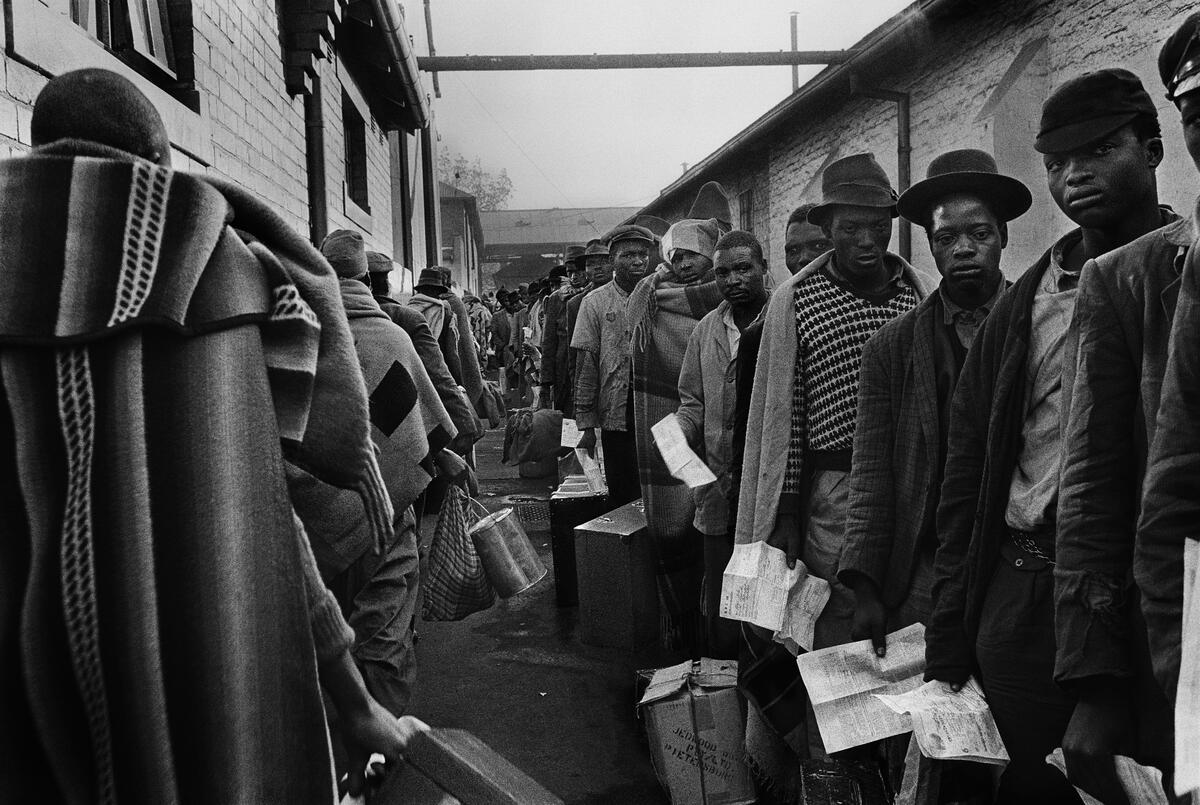

The image at the beginning of this essay was made by Ernest Cole and is captioned: Contract-expired miners are on the right, carrying their discharge papers and wearing “European” clothes while new recruits, many in tribal blankets, are on the left. This image speaks to everything you need to know about the conditions that Black people endured in South Africa during Apartheid, conditions still evident to this day. The exhaustion in the individual faces of those being discharged is visible; it’s also seen in the posture of the new recruits reporting for work who will undergo the same exploitation in the concentration mines. This is where the family foundation was destroyed. The discovery of gold and diamond in the 1800s resulted in an influx of African migrant workers into urban centers like Johannesburg. The labor system in South Africa involved a temporary contract that allowed Black migrants to travel between their homelands and the mines where they worked; this meant that many men were separated for a very long time from their loved ones, living in hostels in urban centers or mining sites, while women and children remained in the rural areas. This created a deep fragmentation in many Black families and identities.

This photograph comes from Cole’s House of Bondage, published in 1967, a book which was banned in South Africa in 1968 because of its exposé on the Apartheid and system, republished in 2022 by Aperture Foundation. What does it mean to be looking at Cole’s work today, the same work he had to flee his beloved home country to publish, and to have the thought that 50 years later not much has changed for Black South Africans? And what does it mean to be looking at the Magnum Photos archive today, an archive that has documented world history from an outsider’s perspective, one that is cherished by many and also criticized for its exclusion of certain voices in the global photographic dialogue? Magnum is known for a tendency to always be looking at the “other,” a process that always holds an element of making a totalizing image. It is an approach that lacks sensitivity to the ways in which images are made, labeled and reproduced, an element of one-sidedness.

And so does it mean for African photographers who have been the subject of this othering to engage with this archive and respond to it? There remains much important work to be done, not only by these four photographers but also by Magnum Photos as an organization. This dialogue with the archive cannot be a one-time project, but rather viewed as an important way forward in transforming the agency, an invitation to a way of seeing the world. It is time for the “other” in these images to become their keepers, to reclaim their identity and replant memory.

DECOLONIZING THE CAMERA

To diagnose a problem is not a cure. Photographers of color are faced with the burden of the legacy of photography and this will mean coming up with different ways of decolonizing the camera and finding ways to collaborate and make images that matter. This will not be an easy process but it will be a necessary and important step. We are the generation that will replant a seed that was uprooted from the ground and reclaim our memory.

Coming back to the title of this essay, what does it mean to be a “Cole of Tomorrow?” For me it is finding ways to make images that matter, to be critically observant of the world, both in the sense of our immediate surroundings, but also the world as a globalized whole.

All four of the photographers on this project engage in the exercise of being critically observant. Haneem Christian’s work looks at a community that has always been othered, the queer community of the Cape Flats, a community that they are a part of and one they want to create an archive of that not only acknowledges its existence but celebrates it. Tshepiso Mazibuko’s work questions township structures, building on her childhood recollections and trying to find a way to use the township as a framework, not as subject. Tshepison Mabula examines her family archive and her relationship with her father using photography and literature as a point of departure. And Litha Kanda engages ultrasound images, exploring photographically what it means to be expecting and bringing new life into the world.

All these photographers are engaging in the replanting of memory. What this looks like varies but for each photographer it is a work in progress, an act of unlearning, of breaking the connection to the colonial concept of what makes a great picture and bringing to it new knowledge from different places, people and cultural background.

This project has focused on one historical archive, and the engagement has been welcome. Moving forward Magnum, and other institutions holding similar archives, have a responsibility to the Coles of tomorrow. Not only to grant them access to their existing archives but also to grant them membership to the organizations that have othered them in the past. This act of caring will bring back into the archive those who have been excluded and othered in the past, enriching the resource and building a legacy that better represents our contemporary world.

“The House of Story” features the work of photographers Haneem Christian, Litha Kanda, Tshepiso Mabula ka Ndongeni, and Tshepiso Mazibuko. Each photographer was mentored by Lindokuhle Sobekwa and Candice Jansen. The publication was designed by Franklin Vandiver.

The project and publication were supported by the British Council #SouthernAfricanArts and Rubis Mécénat as part of the Of Soul and Joy project, and managed by Sonia Jeunet, Global Education Director and Emily Graham, Cultural Commissions & Partnerships, at Magnum Photos.

To learn more about the project, a webinar will take place in April. Sign up to the weekly Magnum Field Notes newsletter for updates.