Digitizing the Color Archive

In its ongoing mission to uncover and make public its vast archives, Magnum Paris has begun digitizing its thousands of color slides, with the help of the European Commission and a consortium of partners. Anna Sansom reports.

Nearly a decade after Magnum created a digital archive of its vast repository of black-and-white prints, the agency has begun a similar process with its color holdings.

Magnum first undertook this mammoth task as an act of discovery — to find out what gems might lie within the dozens of boxes and filing cabinets in its offices in London, New York and Paris. Then, once logged and processed, the photographs could be accessed, researched and promoted via the agency’s culture and licensing divisions, making visible what had lain hidden for decades in many instances.

The work had the dual advantage that, once properly archived, the images are ‘safe’ in a digital sense; should anything ever happen to the originals, the digital archive serves as a backup.

Yet, despite the volume of images that were digitized over the last decade, the archive represents just a fraction of the material that photographers have shot and edited over the years, most of them holding on to their own originals from which the prints were created — originally designed to promote the work of the photographers in newspapers, magazines, books and exhibitions.

The black-and-white prints were digitized first, in part because they were perceived as more valuable. “Up until relatively recently, black-and-white was still the predominant choice for most Magnum photographers,” explains Ana Cruz Yábar, who was until recently the Global Head of Heritage and Archives, based in Magnum’s Paris office, speaking in September. “Color wasn’t as well regarded, especially in photojournalism. Photographers considered black-and-white to be more noble, even though many newspapers and magazines were requesting color to illustrate their stories.”

Magnum outsourced the digital archiving of its black-and-white prints to a production company, but for the color material, the agency decided to do it in-house. Having previously worked as a collection manager in Berlin and Geneva, Cruz Yábar was hired as manager of the Magnum Endowment Fund in 2018.

"What good is it if no one can access it to create new narratives? "

-

The year previously, while on a trip to New York, where she met professionals working on estate planning, she’d become interested in the legacy management of photographic archives. This led to her organizing two workshops for Magnum — the first on analog archives and legacy planning, the second on digital archiving — that gathered more than 70 photographers and estates. Cruz Yábar also produced booklets with practical tips on digital archiving for those attending the workshops.

“After the workshops, we noticed that many photographers needed support in archiving and were seeking advice on legal matters such as inheritance taxes, on how to legally secure heirs with access to their digital accounts and platforms, or about best practices to donate to museums,” she says. “The younger photographers seemed to also develop a new awareness about the value and urgency of the archive that they weren’t aware of before.”

Determining that Magnum needed to develop the capacity to archive its color photography itself, Cruz Yábar suggested a partnership, helping form a consortium with four European partners: Spéos photography school in Paris, the Institute of Art History in Zagreb, the Office for Photography in Zagreb, and the University of Deusto in Bilbao. The consortium won a grant of €200,000 from the European Commission that helped the team to design an innovative training program and to embark on an ambitious two-year project titled, ‘The Cycle: European Training in Photographic Legacy Management,’ towards the end of 2020.

The aim was to “conceive a new way to process archives through training and hands-on experience of trainees,” says Cruz Yábar. “The challenge is about how we can deal with the mass of the analog archive. In an environment where analog is so expensive to digitize, we need to find new ways.”

Besides establishing a “transnational exchange of knowledge and skills” in photographic legacy management, the consortium designed a training program that included four-month-long residencies in Paris and Zagreb to develop their skills and learn about audience development and the management of artistic and cultural projects.

For the purposes of this interview, I met Cruz Yábar in the northeastern outskirts of Paris, at the warehouse where part of Magnum’s color archive is kept. The facility provides storage for numerous French museums, and inside Magnum’s room, there are hundreds of boxes and filing cabinets lining the walls containing works by around 60 photographers that the agency distributed between the 1940s and the early 2000s.

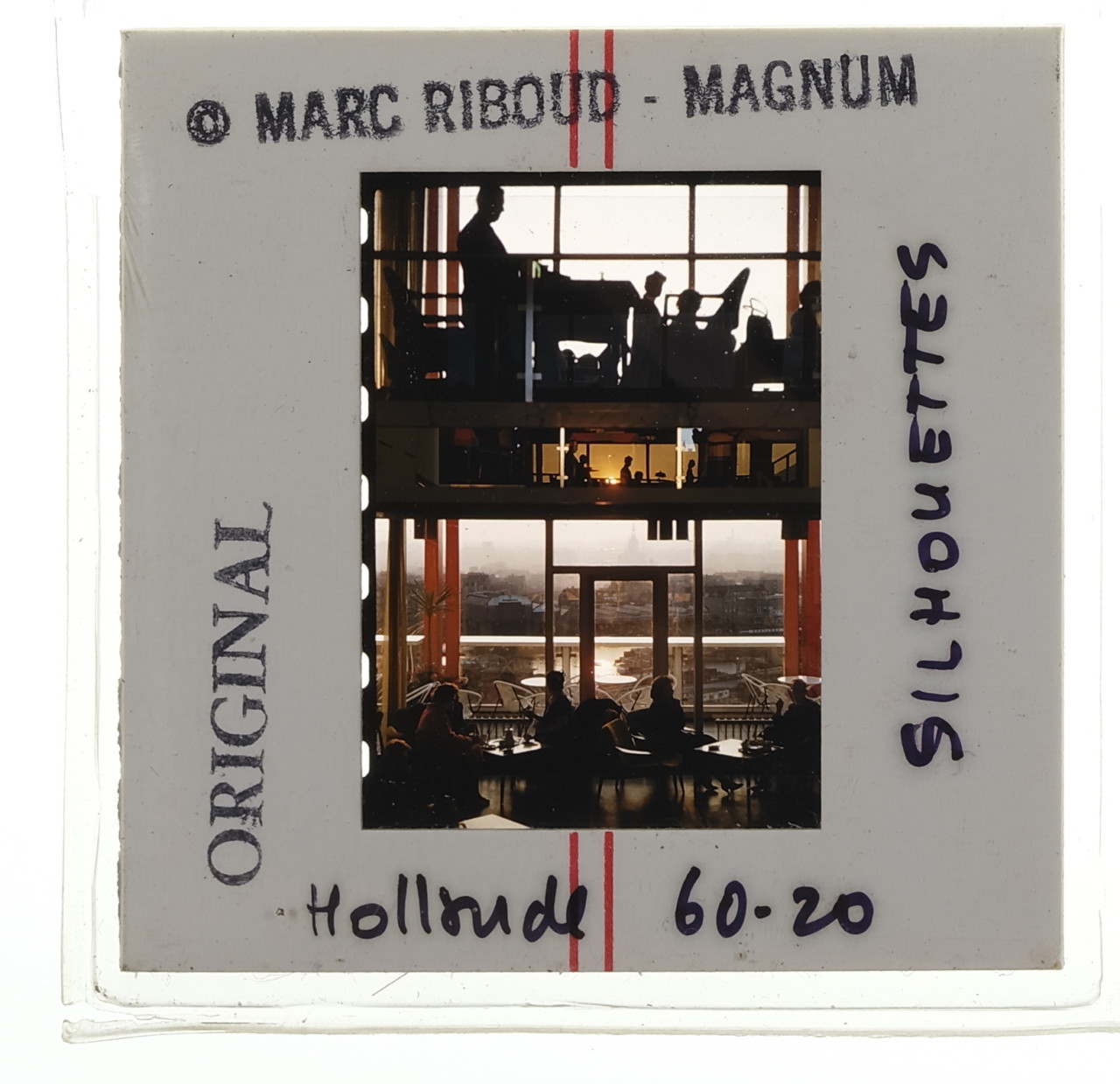

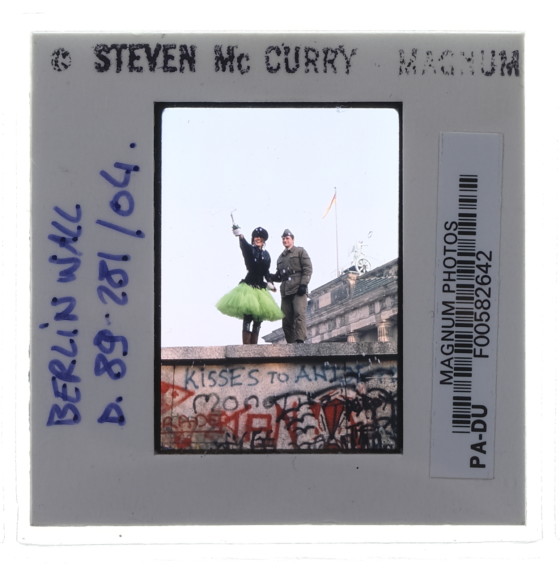

“Approximately 750,000 color slides are housed in plastic sleeves kept in 47 metal cabinets here,” Cruz Yábar muses, as she surveys the room. Each slide sleeve has a descriptive label on the top that usually identifies a country or theme, such as ‘CATASTROPHES’ or ‘SILHOUETTES’ or ‘COREE DU NORD ROUGE’.

The majority of Magnum Paris’ physical archive is held in a building called the Fort de Saint-Cyr, a preservation and photography laboratory that belongs to France’s ministry of culture in Montigny-le-Bretonneux, southwest of the capital. Magnum installed most of its Paris archives there after creating the Magnum Endowment Fund in 2010, a non-profit foundation created by the late Iranian photographer Abbas and supported by Martin Parr, Josef Koudelka and Susan Meiselas, among others.

“We established a partnership whereby the French ministry of culture would make space and resources available to Magnum so we could better preserve our archive,” Cruz Yábar says. “Having an archival institution that could support us was very important because Magnum as an agency is focused primarily on the promotion and dissemination of the work of its members.”

Organizing the digital archive is complementary to the physical archive. “It’s all very well to buy new boxes to store everything in, but what good is it if no one can access it, use it and reflect on it to create new narratives and interpret it through research? So, it was important that this form of preservation was sustainable — so that the archives can be used to publish pictures, create exhibitions, provide new pictures for the press and launch educational projects.”

Magnum started planning a shift toward a digital infrastructure as early as 1991, when it drafted a new archival strategy responding to the oncoming digital revolution. A digital database for Magnum’s archive was created in the 1990s, but initially, it was only accessible internally, so clients were only able to consult the physical collection. It was not until the early 2000s that the database was opened up to clients and the wider public.

Due to the complexity of archiving, and the time and costs involved, agencies such as Magnum have struggled to process their vast treasure troves of images in all their forms and formats. And, as Cruz Yábar points out, “Archival institutions are facing significant processing backlogs that reflect negatively on them in the eyes of researchers, donors and resource allocators.”

Far more still needs to be done. The process of digitizing the color archive revealed that Magnum’s archive is incomplete. Much of the photographers’ corporate work from the 1960s and 1970s was never added, for example, and a lot of work went missing after it wasn’t returned by clients. But one of the biggest problems is that some photographers and estates are not archiving material properly or are failing to make their archive accessible.

“Many photographic archives are held in private hands, often by the photographer’s family who, more often than not, lack the specific competences and knowledge on how to open them to the public,” says Cruz Yábar. “This triggers the question of how we could contribute to a more efficient, sustainable model of preservation and promotion of photographic archives.”

Magnum encourages its photographer members to make a digital archive of their own work but, of course, finding time in between working on projects, publications and exhibitions can be difficult. Sometimes, photographers learn the hard way that they need to invest time into digital archiving. For example, in August there was a fire at Raymond Depardon’s house in Paris where he keeps most of his life’s work, following a lightning strike to his roof.

“In his misfortune, Raymond was lucky, because [thanks to a neighbor who alerted them] the firefighters didn’t extinguish the fire with water but with chemical foam, which did far less damage to his work,” says Cruz Yábar. “The contact sheets stored in his attic escaped the fire and so did most of the prints. The negatives, which were stored in the basement, weren’t affected. But this event made Raymond realize the need to store the archives in proper conservational conditions, and Magnum has supported him technically in this action.

“Raymond is still working tirelessly on exhibitions and publications and so he needs quick access to this material, and this awareness prompted him to digitize his contact sheets.”

Undoubtedly, legacy planning is a major topic of debate in the world of photography. Last year, Magnum and the Institute of Art History in Zagreb organized a three-day conference, ‘Bringing Down the Archive Fever‘, in person and online, in which 27 international professionals presented papers.

A collection of essays based on those papers will be published in January, online and in print, with contributions by keynote speaker Constanza Caraffa, director of the research laboratory Photothek at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, Sandra Križić Roban, researcher at the Institute of Art History in Zagreb, and Cruz Yábar.

Meanwhile, developing and improving access to Magnum’s digital archive is a never-ending task for the agency and the rest of the consortium.

• For further information on The Cycle: European Training in Photographic Legacy Management visit here.