The King’s Coronation

When Henri Cartier-Bresson was sent to London to photograph the coronation of King George VI, he turned his back and photographed the crowds instead. Colin Pantall talks to Clément Chéroux, the curator of a new show featuring his pictures from the 1937 assignment.

What happens when you send a photographer from a Communist newspaper to photograph a coronation? What happens when that photographer is Henri Cartier-Bresson, a man who combined surrealism, documentary and photojournalism in a single click of his Leica camera?

The coronation was that of King George VI (the grandfather of King Charles III), the year was 1937, and what Cartier-Bresson didn’t show was as important as what he did show.

“What is amazing for me is that you are working for a newspaper, you have an assignment to photograph the coronation of the king, and you decide not to photograph the king,” says Clément Chéroux in a call from Paris, talking about one of his first projects since joining Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson as its director last December.

Chéroux has taken the pictures from this assignment and put them together as an exhibition at the foundation, The Other Coronation, showing until September 3, accompanied by a book that he edited, published by Thames & Hudson.

"The king, the procession, the ceremony, the spectacle is of no consequence to him."

-

One reason Cartier-Bresson didn’t photograph the king is that Ce Soir, the recently formed Communist daily he was working for, didn’t have sufficient prestige to get the young photographer accreditation for the Palace of Westminster.

At the same time, the decision not to photograph the king, the ceremony or the procession was partly political, says Chéroux.

“A few years earlier, a Communist Party magazine called Regards published a statement where they clearly say, ‘We are not interested in the wealthy. We want to show the people, we want to show the workers.’”

And that’s what Cartier-Bresson did. He photographed the throngs of onlookers who crowded the parks and pavements of London, who climbed trees and statues to get a glimpse of the newly-crowned monarch. Most of all, he photographed the gaze of the spectators — the very act of their looking as they engaged with the spectacle before them.

It’s a way of photographing that has at its heart the absence of the king himself, an absence that Chéroux believes was part of Cartier-Bresson’s subversive approach to photography. In its place comes an ambivalent celebration of British working class life in all its glory.

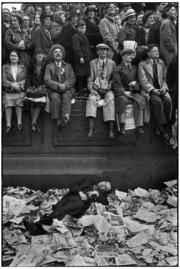

It’s a celebration most evident in the best-known of Cartier-Bresson’s coronation pictures, that of a crowd of people sitting on a wall in Trafalgar Square, all flat caps and Sunday-best suits. At the bottom of the picture there’s a man lying asleep in a pile of discarded newspapers, the front page headlines and photographs of the king making up the detritus of the day.

Cartier-Bresson has his back turned to what they are looking at. The king, the procession, the ceremony, the spectacle is of no consequence to him. That is one layer of subversion, says Chéroux.

The second layer of subversion is his focus on the apparatus by which people follow the procession, the way they get a view of events when that view is blocked by a wall of people. The most sophisticated way of viewing was with a cardboard periscope.

“I want to show you something,” says Chéroux, disappearing from the screen to bring out one of the original periscopes used for the coronation. “You have to look here and you see the spectacle through it. So the people that are looking in the periscopes are facing the king, but they are using a super symbolic object for two reasons.

“First, it was used during the First World War by the British Army to look at the enemy. So this is the kind of device that you use to look at the enemy, which in the context of the people versus the king takes on another interesting, symbolic value. Second is the fact that the periscope is a very aristocratic, scientific game that was used in the 19th century by the children of aristocratic families. So it’s a re-appropriation by the people of a game or tool or scientific toy that was used by the aristocracy.”

A cheaper and simpler way of viewing was by using a mirror stuck to the end of a stick. Hold this in the air, turn your back to the king, and you might get a fleeting glance of the royal carriage as it passes by. So we see people craning their necks, squinting into the sky as they try to maneuver their mirrors into a position to reveal a glimpse of a reflection of a king.

“I think he chose to do that because he had a kind of surrealist background. And a surrealist background is a subversive background,” says Chéroux. “You do the exact opposite of what you’re supposed to do.”

This idea is echoed by surrealist fascination with mirrors, reflections and viewing machines. Though made in 1912, Eugène Atget’s photograph of a crowd of Parisians viewing a solar eclipse through darkened glasses, heads craned upon the distant spectacle, became a key surrealist image, one that finds multiple echoes in Cartier-Bresson’s take on the coronation. There are the same craned necks, the same squinting eyes, the same reflected gazes and the same mass of people.

Chéroux also sees Cartier-Bresson’s focus on the gaze of the viewer as reminiscent of Foucault’s writing on Velázquez’s painting, Las Meninas. “Foucault writes about the position of the gaze,” says Chéroux. “Where are you looking from? What is your position? Is it a position of power or is it a position of submission? I would say that 40 years before Foucault, Cartier-Bresson already understood that the position of the gaze is a position of power.”

The suggestion in Cartier-Bresson’s pictures is that the back-turned position is one of deep ambivalence. There is fascination from the spectators but there is also a laissez-faire dismissal. The king has been turned into a spectacle, a being who can only be glimpsed by the spectator through a reflection in a mirror.

In Cartier-Bresson’s pictures, he can only be seen in the mise en abymes (a picture in a picture) of the discarded newspapers the sleeping man has as his mattress, or the royal portraits the street hawker sells to passers-by. He is nothing more than a reflection and not a particularly sacred one at that.

In times gone by, you would be executed for turning your back on the king or sleeping on an image of the king. Even in the present day, there are places where you could be imprisoned or worse for violating the image of a country’s leader.

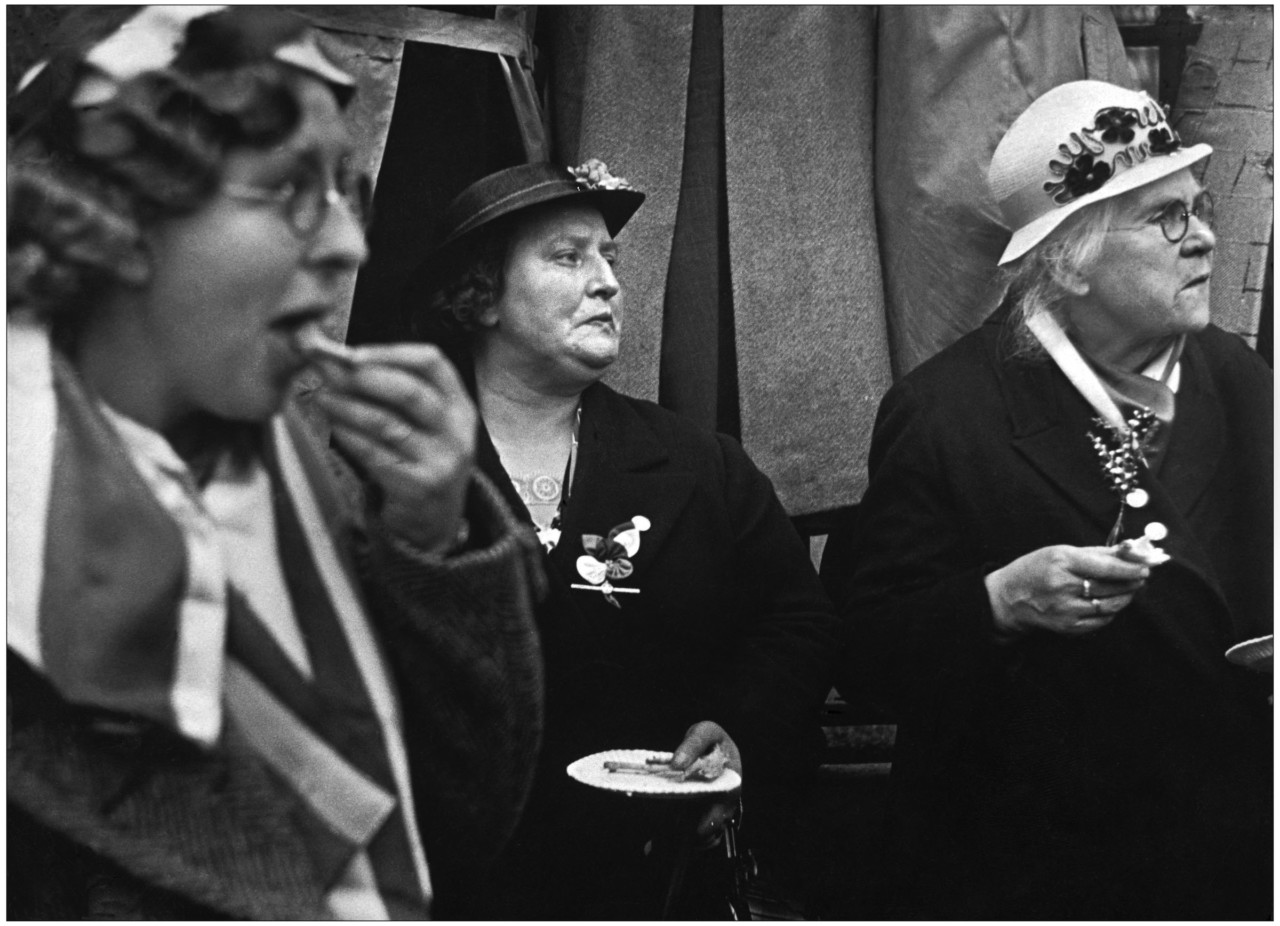

In the exhibition and accompanying catalogue, there are texts that show a fascination with the bad dress, bad food and bad taste of the British. Cartier-Bresson writes to his wife about how in Britain, “the high class gives itself in spectacle to the people who of the street who just cheer them. It’s a funny old country. Everybody adores old customs, which have no more use anymore.”

It’s a mild statement for somebody who, according to Chéroux, “…was deeply involved with communism in the 1930s,” but class is a driving factor both in the images Cartier-Bresson made and the excellent supporting texts that accompany the exhibition.

Class is there in his pair of pictures of a curly-haired boy. In the first, the boy stands on the shoulders of a man who is probably his father, his mouth open in some kind of shout. In the second, the man is sitting, the boy still on his shoulders but now with a look of exhausted disappointment.

The exhibition also includes clippings of press coverage from newspapers from France, the UK, Switzerland, the USA. Where these almost feature images of pomp and ceremony entwined with economic, religious, colonial and military power, Cartier-Bresson’s images almost have a sense of disappointment about them, a feeling of, ‘Was that it?’

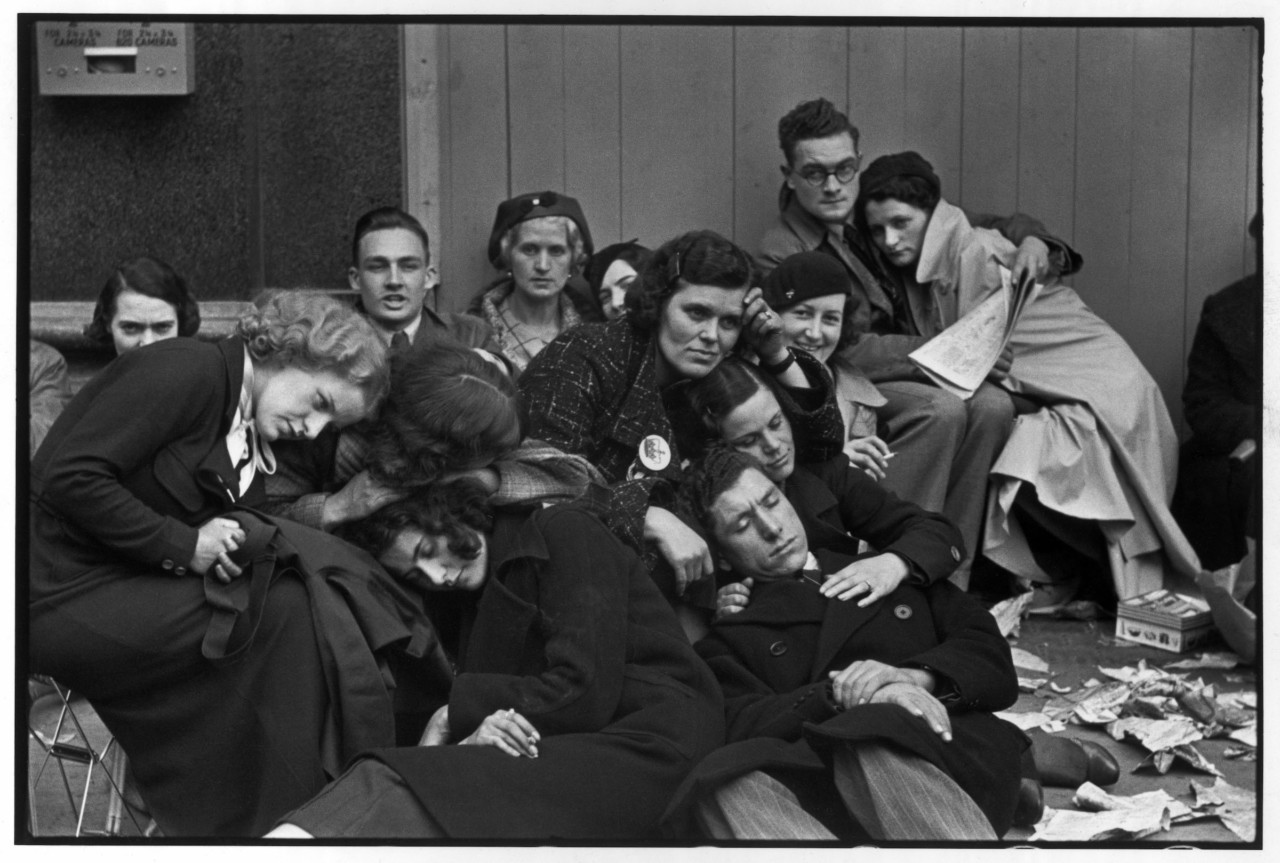

There are images showing people exhausted by the day’s affairs, collapsing into a heap on the pavement after a day of standing and stretching. Overwatered and underfed, there is the sense that the coronation with all its trappings was but a sideshow in the main event of drinking and debauchery.

A text by a Ce Soir member of staff, Henriette Nizan, describes Britain at the time. She describes a place of chaos. The miners are about to go on strike, there are no buses running. She attends a meeting of 3000 fascist blackshirts. There is tuberculosis, mass unemployment and the most abject poverty.

Nizan attends the opera the night before the coronation and then wanders the streets of London with “a very polite, very kind young man” — Cartier-Bresson. “I had no idea what mass hysteria here in London might entail,” she writes. “People, most of them drunk as lords on beer and whisky, were lounging on top of their vast Sunday Times, the perfect protective matting, and couples — a great many of them — were making love in the streets and gardens, surrounded by children. Humans, rutting en masse like animals. Our friend, Cartier-Bresson, was taking photographs, a fellow witness to the fantastical scenes.”

Unfortunately, none of these photographs are in the exhibition. “In 1939, Cartier-Bresson reviewed his entire archive of negatives and decided to cut all the strips into individual negatives,” says Chéroux. “He also decided to destroy some of these negatives. We know that there are prints for which we don’t have the negatives, so we are almost sure that some of the negatives from the coronation were destroyed.”

There are thumbnails of all the surviving negatives, including images that Cartier-Bresson made to show the social backdrop to the coronation, the flow of life that forms the underlying narrative to the event. There are pictures of ladies in Salvation Army dress, soldiers in dress uniform, Indians come to view the procession through a periscope. And there is a blind war veteran holding a sign saying ‘Undefeated’ selling packs of cards decorated with the pictures of the royal couple — the ultimate expression of Cartier-Bresson’s fascination with the British obsession for “…old customs, which have no more use anymore.”

………………………………

You can order a copy of The Other Coronation from the Magnum Shop.