Stuart Franklin’s Traces of Trees

The photographer shares the story behind his latest photobook, "Traces," published by Dewi Lewis in fall 2023.

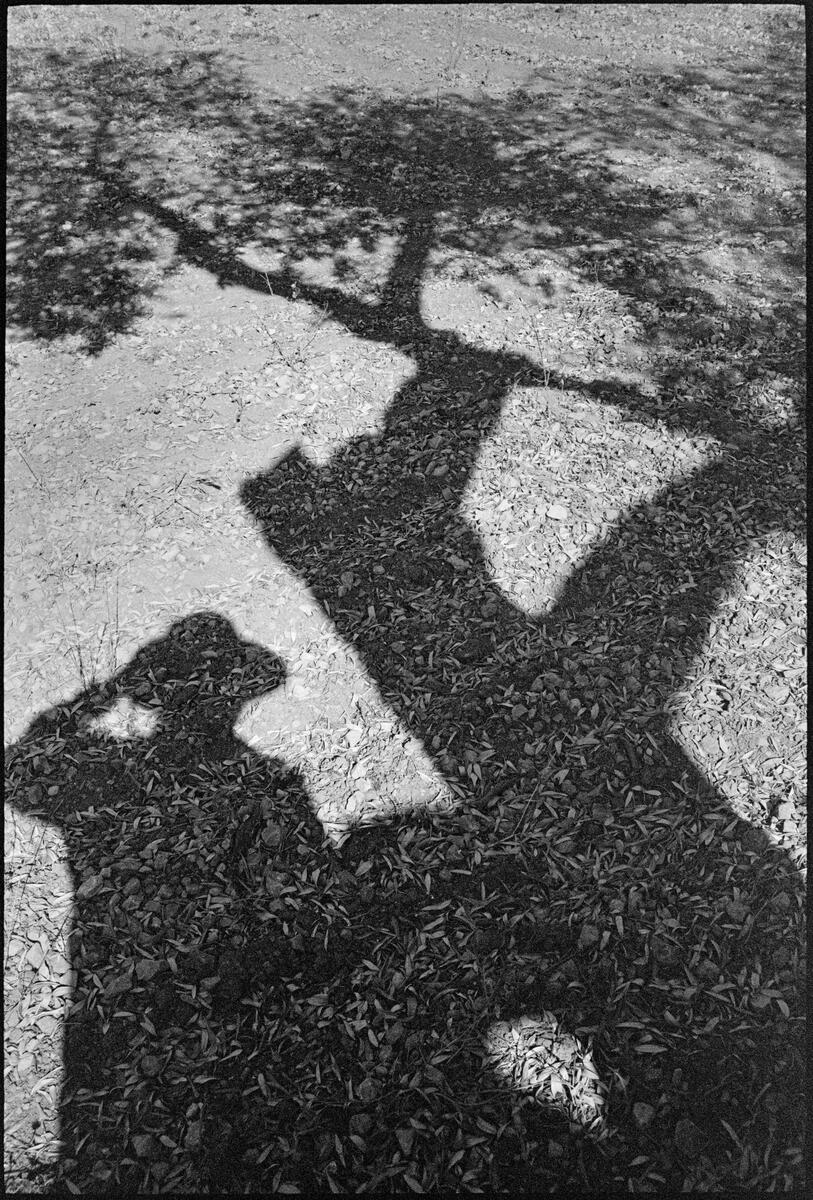

“Landscape and memory combine, for me, as a means of seeing and documenting the world,” writes Stuart Franklin in the introduction to his latest photobook, Traces. “Here the emphasis is on trees. Their presence (or absence) out there today can rarely be separated from human history and human intervention.”

The photobook, published by Dewi Lewis in fall 2023, appears to be a sequel to Franklin’s first book on the subject, The Time of Trees, published in 1999. In this first book, the photographer presents a journey across five continents, exploring the boundaries between nature and society; how we live in the presence of trees, and how we both utilize and usurp them.

In one image from Tanzania in 1998, for example, two tribesmen are seen huddling inside the hollowed-out trunk of the enormous baobab tree, sheltering from the cold, or from “prowling lions,” as Franklin writes in the accompanying caption. In another from the same year, we see a line of New York high-rise buildings towering ominously over a row of trees in Central Park, which in turn, tower over a small child leaping from one rock to another in the foreground. Humans are small in the face of nature, yet their impact is enormous.

While the human imprint, big or small, seems omnipresent in The Time of Trees, Traces sees Franklin shift his gaze away from “cohabitation” and toward the trees themselves. It is nature, and his perception of it, that dominates in this second book, as the photographer expands his decades-long fascination with the subject.

A Personal Journey

One of the two citations to open Franklin’s latest book is from Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain: “… The eye sees what it didn’t see before, or sees in a new way what it had already seen.” For Franklin, Shepherd’s quote about perception links to memory. “In Traces,” he explains, “I have explored many ways in which trees — and the forms that they embody — trigger memories.” And he begins by telling his own story of the Proustian moment that inspired the book.

“I remember clambering through the Savernake Forest in England in 2022, when I spotted several tall, knobbly oaks looming about the bracken, eyes staring down at me,” he writes. “I was struck by the thought that these bold forms were a flashback to my childhood, to early memories of grownups.”

“Residential nursery staff and foster parents — benefactors and ‘benefactresses,’ to borrow Charlotte Brontë’s term — were what substituted for parents from the age of five. Adults were strangers who wielded the pronouns we like a cosh (eg we think another home would suit you better). There were angels of course and I still see them in the forest (this book is dedicated to two of them), but those frightening tall people, under whose charge I was placed, are still assembled somewhere in my psyche.”

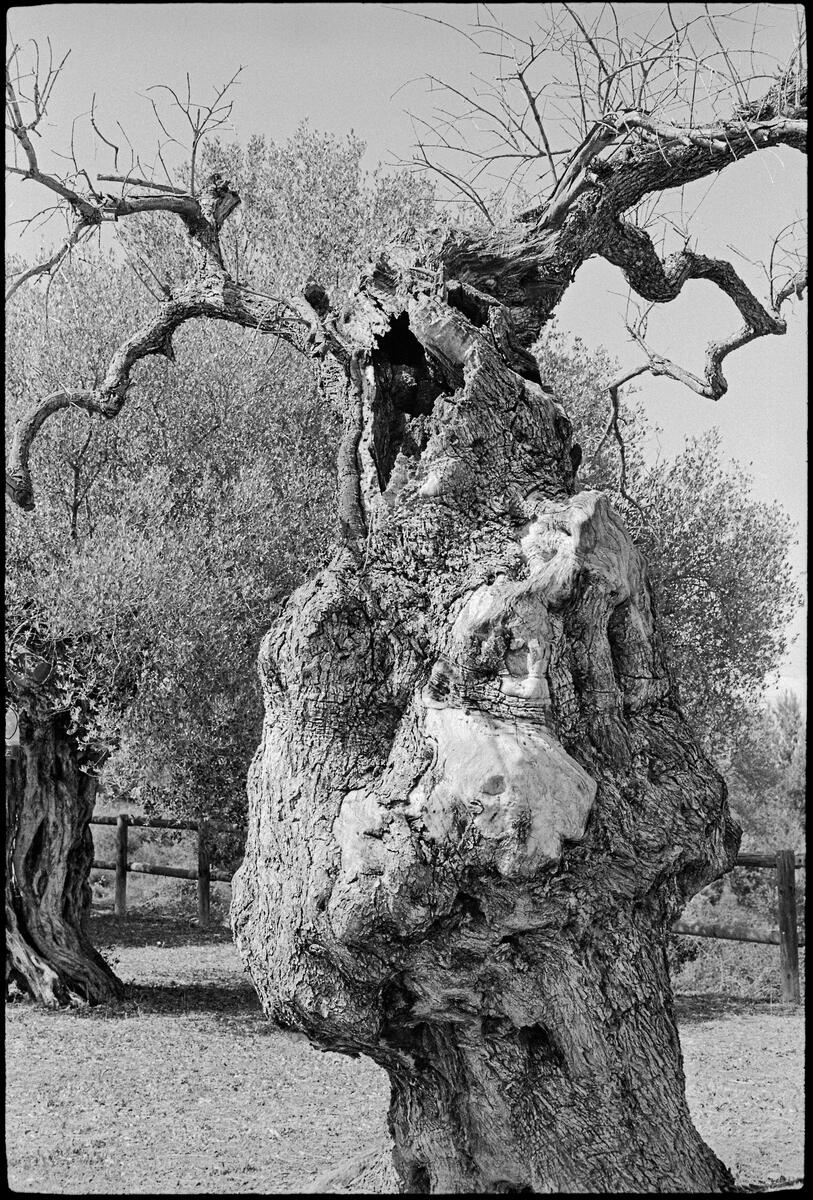

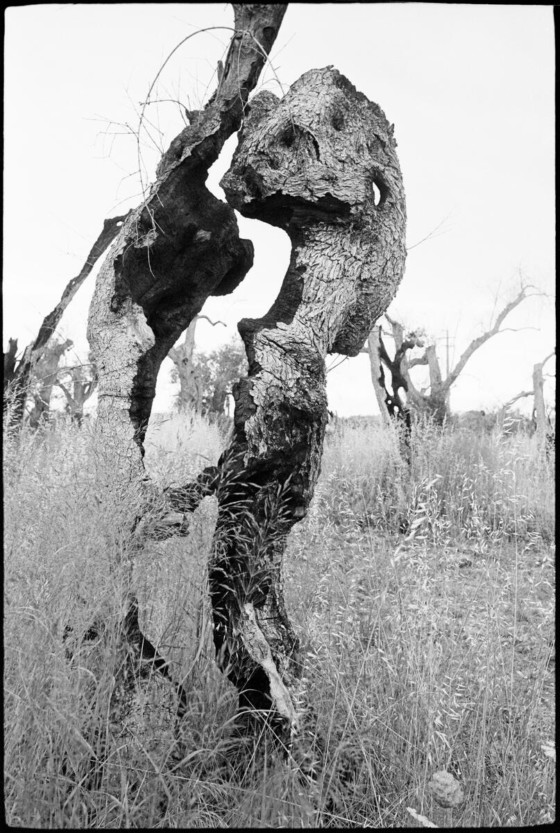

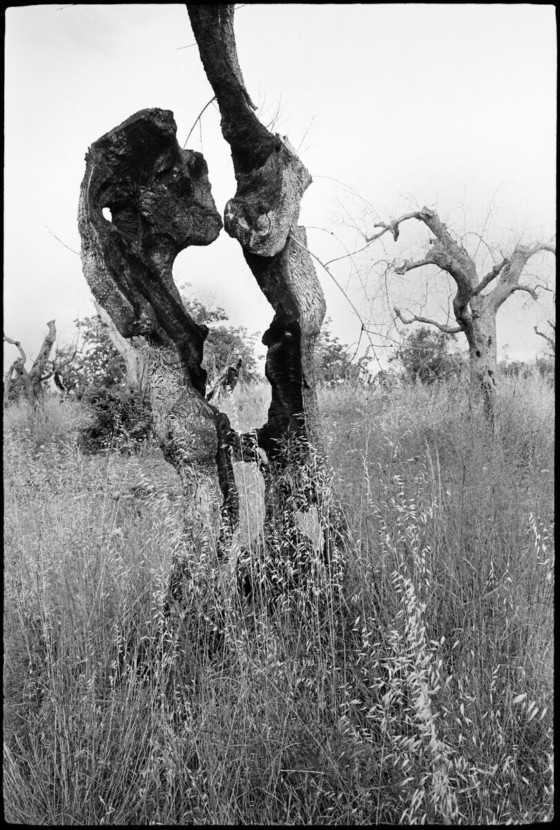

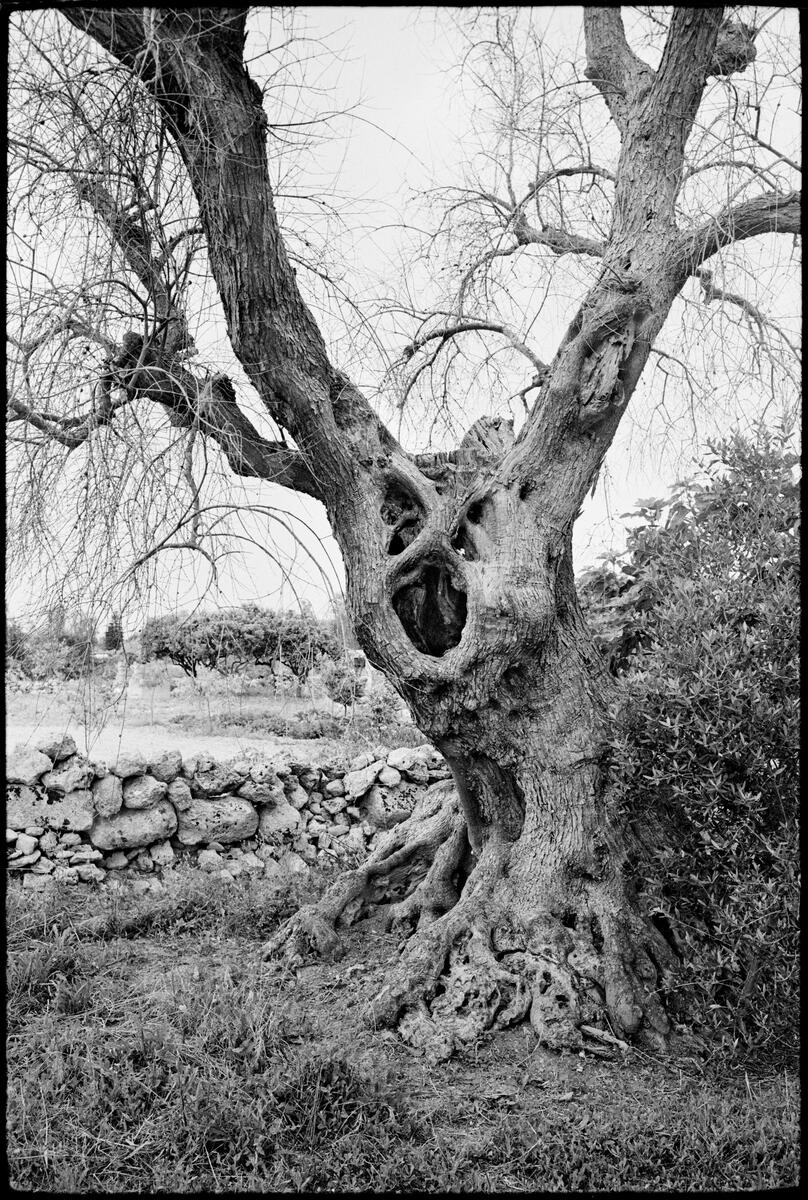

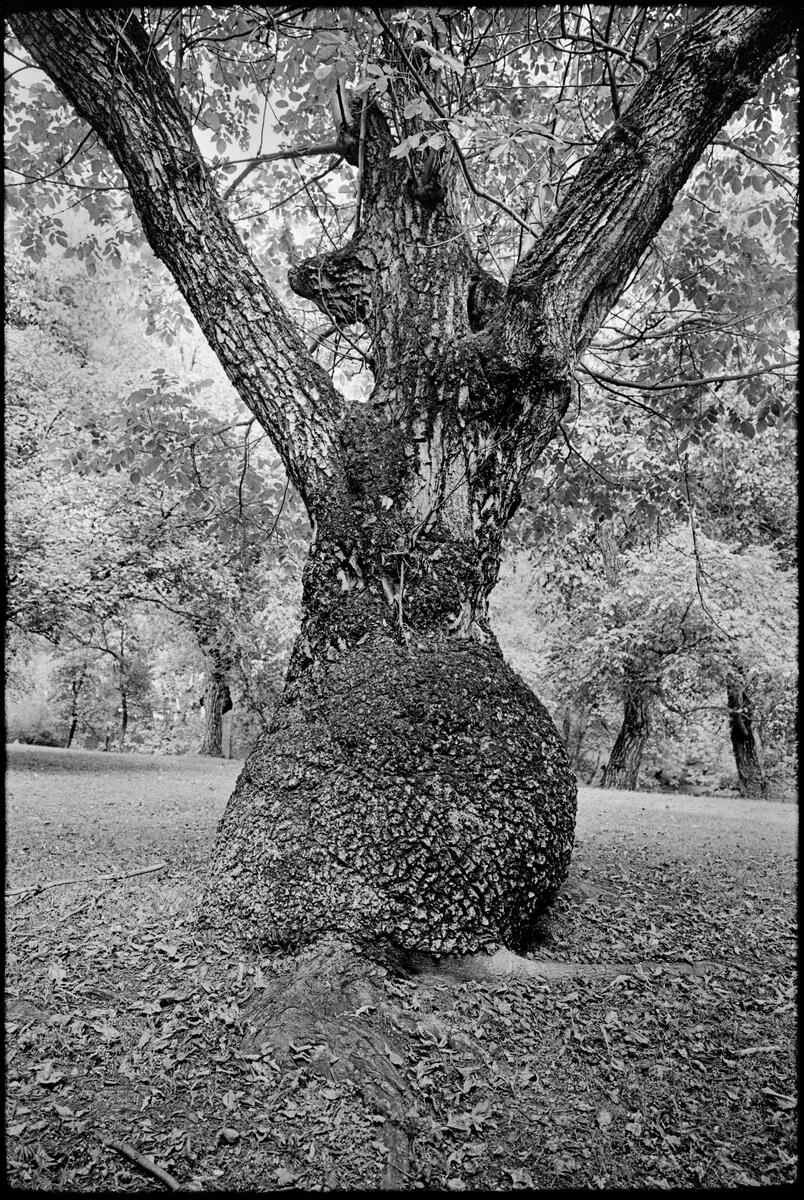

And through many of the images in the book, Franklin appears to personify the trees through his lens. Faces, angry and warped, howling or gaping, stare out at us. Their forms, unmoving to the human eye, are often fixed in positions that mirror human movement. In one, a branch appears like a clenched fist. In another, the shell of a burnt olive tree in Puglia has broken in two, with its two parts now as if fixed in a permanent embrace.

“Only now, in my sixties am I able to return and make some sense of the past,” Franklin explains, “through recognizing the immanent significance in these trees and the disfigured faces that stare out at me.” Traces can therefore be interpreted as a book of profound, personal reflection on the significance of these trees on our psyche, rather than our physical state or environmental circumstance.

From Ancient Mayan Temples To the Canals of Amsterdam

Yet despite this deeply personal core, Franklin in parallel remains faithful to his art of thorough documentation. The 170 images of the book are divided into three sections, each covering different geographies and natural features with their own underlying narratives.

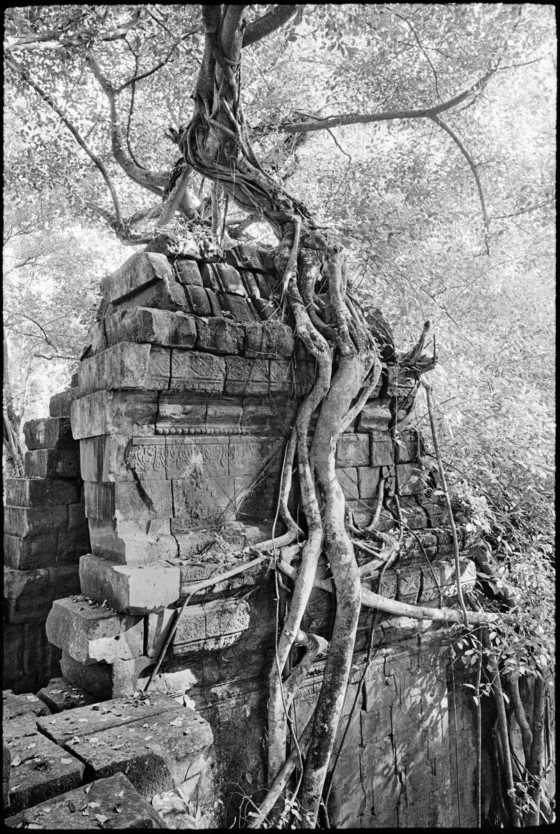

In the first section, Franklin documents temple spaces and ancient cities in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malta and Mexico.

At the site of Beng Mealea, an ancient temple from the Angkor Wat period in Cambodia, Franklin photographs the “Beng” tree, which due to intense deforestation is now on the red list of endangered species. “The tree that I photographed, on the path to the temple, appeared to be scowling in disgust,” he writes.

The second section focuses on the survival and vulnerability of the olive tree in Southern Europe, before moving to walnut forests in Kyrgyzstan, chewing-gum trees in Mexico, and back to Malta, where the idea for the book originated in March 2022.

Franklin had been in Puglia to explore the impact of Xylella fastidiosa, a widespread bacterial infection that was found in Puglia and that had started attacking the ancient and intelligent century-old olive trees in the region. “In this case their age and intelligence offered no protection,” he explains. “I crossed field after field of gray and dying trees. Some that I photographed were burnt to contain the disease.” From that moment on, he focused on the project intensely, and almost all of the photographs found in Traces were made between March 2022 and May 2023.

In the final section of the book, Franklin shifts his gaze closer to home, and closer to other species of ancient trees — the yew, beech and oak trees in England and Wales.

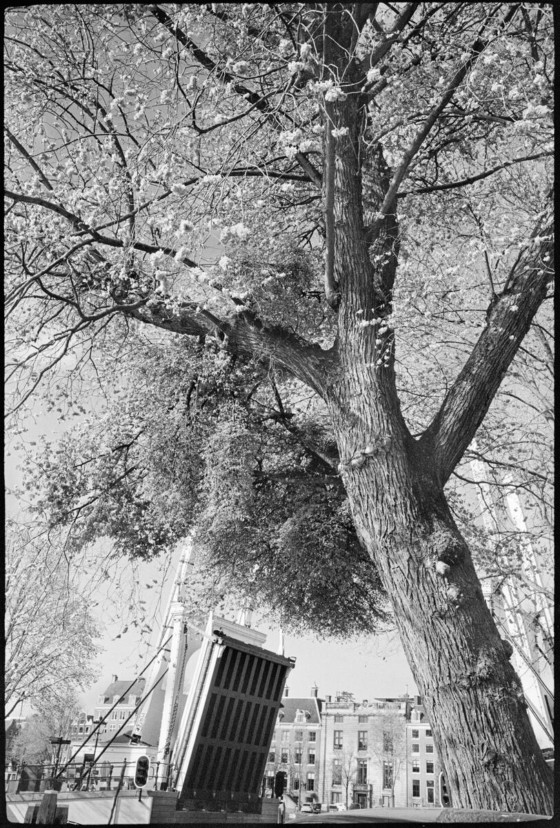

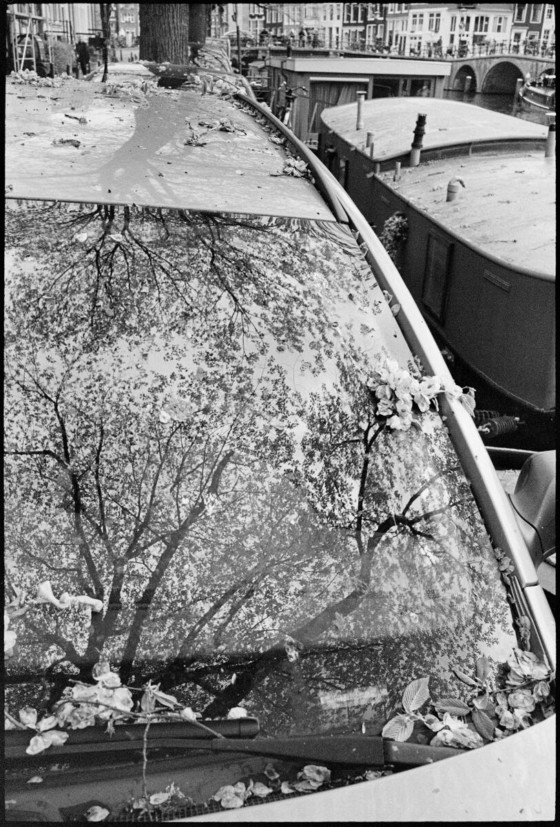

He then moves from the ancient to the modern, visiting some of the youngest trees in Europe: the elm trees that line Amsterdam’s canals. And finally, the closing image of the book is of a young willow tree on the shores of a lake in Møre og Romsdal in Norway — a tree that Franklin himself had tended for ten years.

Franklin’s “Translations”

Accompanying the selection of images are essays from sculptor David Nash, Martin Barnes, Senior Curator of Photography and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and Franklin himself. For Franklin, it is an opportunity to reflect on the 45 years of his photographic career, drawing upon a vast array of influences and inspirations, including the addition of drawing and painting to his œuvre.

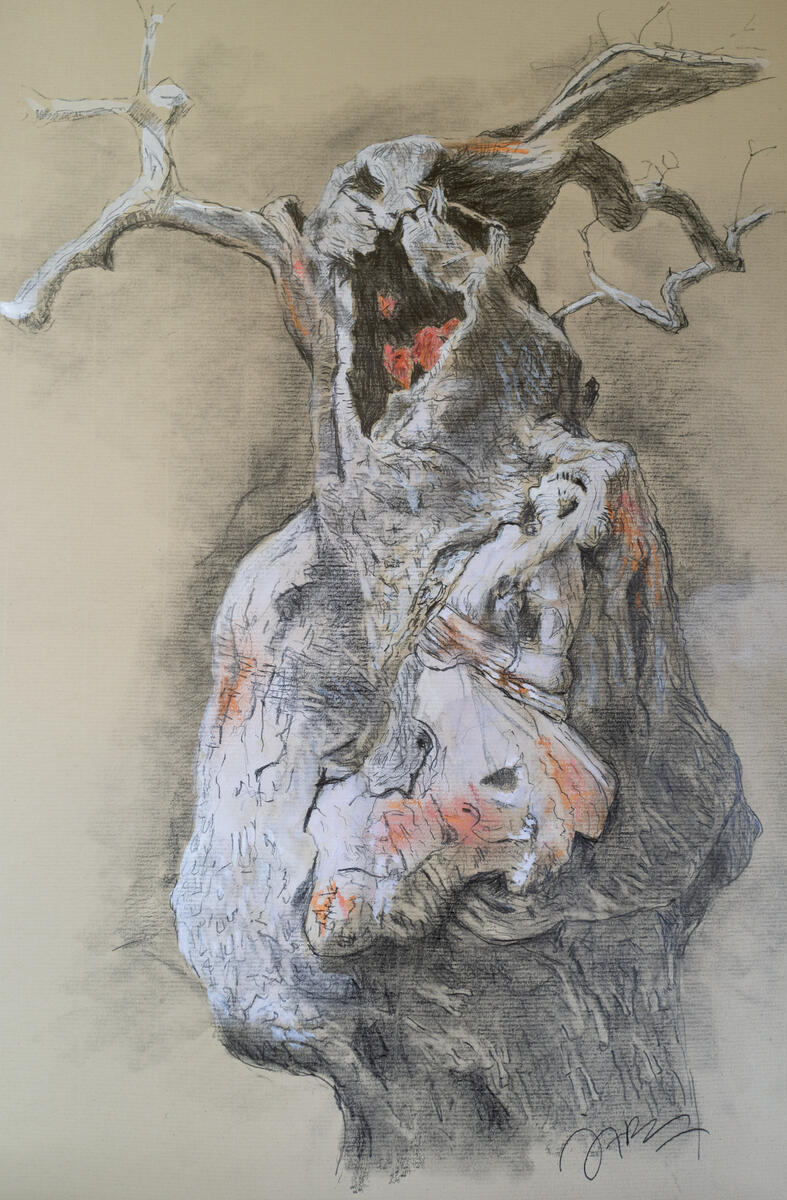

“No matter how carefully the photograph is composed or rendered, the idea behind the picture, that becomes entrenched with every look, can become obscured,” Franklin explains. “To unchain myself from the photographic trace I moved on to draw and paint with the aim of teasing out the associations that initially attracted me.”

Franklin refers to these drawings and paintings as “translations,” and shares several examples from Italy, Cambodia, Spain and Kyrgyzstan. In one example, we see the haunting remains of an olive tree in La Jana. “The drawing now locates the idea close to the symbolist painter Giovanni Segantini’s The Bad Mother series (1891–6),” he explains.

"Drawing and painting have become a parallel approach to working from and with photographs."

-

“Trees have stayed in our memory, and become entwined in our collective cultural memory…” Franklin writes to close the book’s foreword. “Like the banyan tree, the ‘bicycle embracing tree,’ in Wu Ming Yi’s novel, The Stolen Bicycle, or Arthur Koestler’s prisoner Rubashov’s fleeting, final recall in the novel, Darkness at Noon: a boyhood memory of lying in the grass in his father’s estate ‘staring at the poplar branches as they wafted slowly overhead.’ A patch of pale blue sky, glimpsed above a machine gun tower, triggered that thought, the last, before he was led down to the basement to be shot.”

In Time of Trees, published now over two decades ago, Franklin wrote of how it was his attempt to “forge together two genres in photography that have, historically, remained distinct: landscape and reportage.” Now, in Traces, he adds a third, deeply personal element. By sharing his own personal reflection and response to the photographs that he has made, he calls on the reader to look a little differently at the trees before them, to see what they may evoke.

Copies of “Traces” are now available to purchase on the Magnum Shop.

An exhibition is on view at the Leica Gallery in Vienna until February 24, 2024. Join Franklin himself for an artist talk at the gallery on the evening of Friday, February 23. Book your tickets here.