From Paris to Benin: the restitution of the royal treasures of Abomey

Patrick Zachmann captured the process of returning 26 royal treasures of Abomey to West Africa after more than a century in France

Since May 2021, Patrick Zachmann has covered the restitution of 26 royal treasures of Abomey from Paris to Benin, following a law unanimously adopted by the French National Assembly in December 2020. The treasures had been exhibited in Paris since their capture by the French in 1893, first in the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, and then as a permanent collection in the Musée de Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac from its opening in 2006.

Over the past year, Zachmann has captured the process of returning these royal treasures, from being carefully packed up, transported back to West Africa, and exhibited in Benin’s Presidential Palaces.

The 26 works of art are valuable cultural artifacts that help encapsulate Benin’s rich history. The collection ranges from immense ceremonial thrones and statues of Kings Ghezo, Glele, and Behanzin of Dahomey, to smaller pieces such as military uniforms and accessories. Its return last November marked the first time that the Beninese public was able to see the complete collection in its country of origin.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou, President of the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, states: “With Patrick Zachmann’s offer in the Fall of 2021 to document the return to Benin of 26 works from the royal treasures of Abomey, a simple truth had emerged: the historical weight of the moment called for the eye of a photographer who has proven himself to be a great witness of his time.

Eight years after around 100 prints from Zachmann’s series, W. ou l’œil d’un long-nez, entered the museum’s collection, the collaboration with the photographer continues to bear fruit.

Today, both French and Beninese cultural history are richer by virtue of his precise, perceptive and respectful view of his subject matter. I would like to express my gratitude to the photographer for having so aptly remembered an event that signifies long-lasting relations between our two countries – without limits, no doubt”.

Gaëlle Beaujean, in charge of the Africa collections at the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac and Doctor in Social Anthropology at EHESS, provides below a historical account of the royal treasures, how they were originally seized in the late 19th century, and the path to restitution over a century later.

At a time when European powers were dividing up and colonizing Africa, France sent more than 3,000 soldiers to the Kingdom of Danhomè in 1892. The two nations had known each other for a long time: France had already bought prisoners of war from Danhomè under the old regime and then sold them in America. The abolition of the slave trade in the 19th century did not interrupt the relationship, this time based on the trade of agricultural products.

However, the clandestine Danhomè trade continued, but towards Brazil, and the public executions in Abomey, the refusal to cede the village of Cotonou to the French, or the repeated attacks on the city of Porto Novo, already colonized by France, were all pretexts for starting a war. Thus, Colonel Alfred Dodds was appointed by the French government to bring Behanzin, King of Dahomey, to submission.

Firstly, the coastline was bombarded for three days from the ocean, from Ouidah to Cotonou, strategic locations of the kingdom. The French ‘expeditionary column’ then headed for the capital, Abomey, in early September. On November 17, 1892, when Behanzin had to flee northward to organize resistance, Dodds took Abomey and ordered his soldiers to disarm the enemy. They then found a large number of underground hiding places, organized as reserves. Weapons, ammunition, alcohol and artistic objects of the court were hidden and protected. The palaces were burned down by order of Behanzin to leave nothing for the French.

Everything suggests that the objects seized came from these underground reserves, but written records are rare. If the French government did not demand any cultural treasures, the officers and non-commissioned officers went ahead and created collections of war booty on their own initiative.

The conflict ended in 1894 when Dodds captured King Behanzin and exiled him to Martinique.

Appointed general after the capture of Abomey, Dodds gave twenty-six objects from this booty to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, in 1893 and again in 1895. Among them, the royal statues and one of the three thrones were immediately displayed as trophies.

The change in perception in the following decades turned them into works of art, then into objects that were witnesses to Adja-Fon culture after the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro was replaced by the Musée de l’Homme, which is characterized by an ethnological approach. In the early 2000s, the collection was transferred to the Musée du Quai Branly, which opened in 2006, and which decided to place these works in an aesthetic and historical perspective, most notably by recounting the way in which this war booty was constituted.

In 2016, the Republic of Benin officially requested the restitution of the objects, initially refused in the name of the inalienable and imprescriptible status of French national heritage, a status in place since… 1566. On November 28, 2017, President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech at the University of Ouagadougou in favor of “temporary or definitive restitution of African heritage in Africa” kept in France and entrusted Bénédicte Savoy and Felwinn Sarr with a report on the subject, which they submitted in 2018.

France would then undertake at the end of 2018 to propose a law in opposition to the heritage code and in favor of the restitution of the 26 objects seized by General Dodds, to which is added the sword of El Hadj Omar which had been returned to the Republic of Senegal and kept at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris. The project was presented by the government to the two assemblies in July 2020, which consulted a number of specialists. Rejected upon second reading by the Senate, the law was unanimously adopted by the National Assembly on December 17, 2020. It was put into effect by the president on December 24, 2020.

Patrick Zachmann followed the movement of these works, first those presented in the permanent exhibition in September 2021, then the movement of those kept in reserve, then the plinths to be exhibited one last time in October 2021.

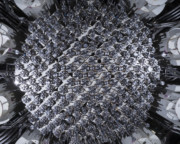

The 26 objects taken in Abomey by Dodds were officially returned on November 9, 2021. They arrived in Cotonou two days later. On February 19, 2022, the Beninese public could finally see the pieces as a complete collection, thanks to an exhibition held at the presidential palace (on until May 22nd, 2022). The Bochio protective statues of King Ghezo, King Glele as a lion-man and King Behanzin as a shark-man are presented; the two immense ceremonial thrones of the Ato ceremony; the throne of Cana, on which the king is represented surrounded by his wives, mounted above enchained slaves; the doors of the palaces; a series of altars in precious metals and iron to honor the ancestors; a wooden stool and a calabash engraved with motifs readable only by the initiated; ceremonial weapons of soldiers; a military uniform and weaving accessories. These are the 26 works of art taken in Abomey by Dodds and now the inalienable property of the Beninese state.

Gaëlle Beaujen’s thesis, L’art de cour d’Abomey: le sens des objets, was defended in 2015 and published by Presses du réel in 2019.