Witnesses: Lindokuhle Sobekwa – Generations of Refugees in Dadaab

Through MSF operations, photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa has met generations of families born and raised in the Kenyan refugee camps, prompting him to question his own vision of what it means to be a ‘refugee’.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), a new book, Witnesses: 50 Years of Humanity, looks back at the major crises of the last five decades. Through the photos and words of those who lived through these events, it bears witness to the difficult mission of providing assistance. The collaboration, between Magnum Photos and Médecins Sans Frontières, available to buy here, was born of encounters that took place in the midst of crisis; whether in the world’s most remote regions, or in areas covered by international camera’s and media. The book is a historical document, made of common experiences that revisit the last fifty years – right up to the present day.

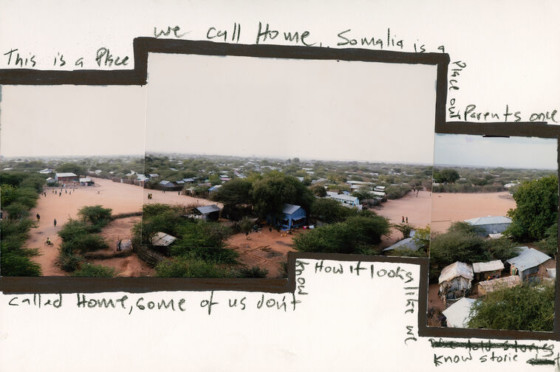

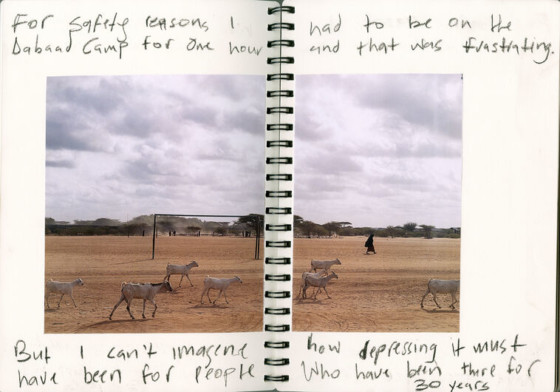

The first camp in Dadaab, Kenya, was set up thirty years ago to host Somalis fleeing the civil war in their country. More refugees arrived in the years that followed—at its peak, the Dadaab Refugee Complex hosted some half-a-million people. Many refugees living in the camps today have been there for three decades; others were born in the camps and have known nothing else.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has provided healthcare to refugees in Dadaab for most of the camp’s existence. Today it is the main healthcare provider in Dagahaley, one of the camps of the complex.

Through MSF operations, photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa has met generations of families born and raised in the camps, prompting him to question his own vision of what it means to be a ‘refugee’.

It sounds strange to me, calling someone a refugee. I have always heard people talking about refugees and refugee camps, but I wanted to see what kind of challenges the people in camps like Dadaab face. Of course, I can’t tell you what their challenges are. The people living there know the realities much better than I do. But I can tell you about my own experience of the place.

I’d been to Kenya before for a different assignment; from a different angle. But this was the first time I’d been to a refugee camp. I didn’t have knowledge of Dadaab. I knew about Somali history and the tensions in the region because we read about it here in my home country of South Africa. There have been numerous xenophobic attacks and killings involving the Somali people who live in South Africa, but no matter what happened to them here, they never returned to Somalia. When I went to Dadaab, most of the families that I interviewed said they would never go home. Home is not an option for them. They would rather go to a different country or stay in the camp, even if it’s a dangerous place.

I remember when the plane was landing; when I saw what Dadaab looked like. I remember I had a feeling I’ve never felt before: nervousness mingled with excitement. The nervousness was rooted in what I had read before going there.

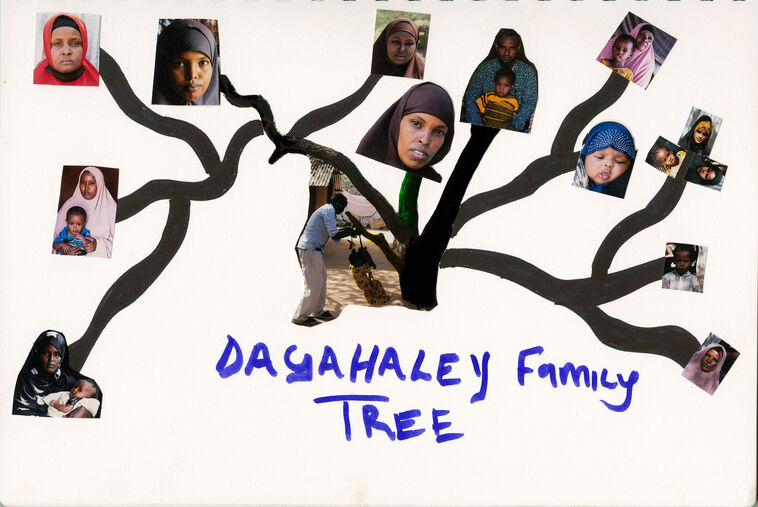

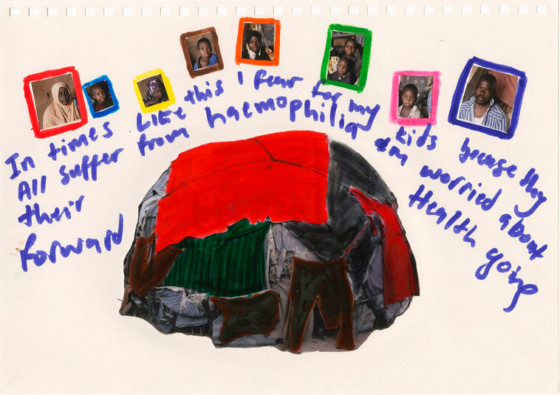

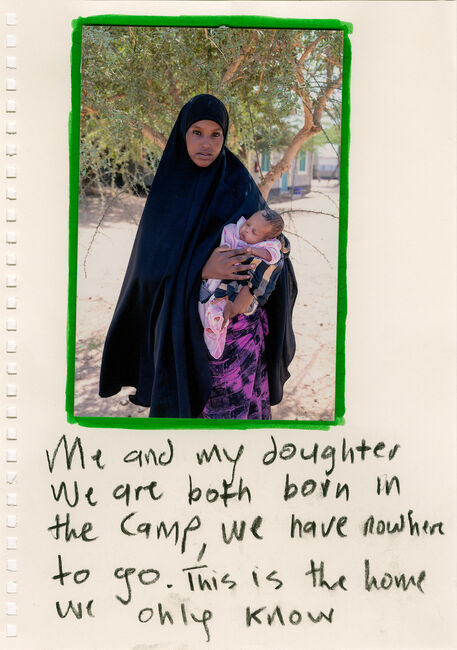

I found unique stories in Dadaab. Before taking portraits, Paul, the MSF communication officer and I interviewed everybody to understand who each of them was, where they were from, and how long they had been in the camp. Some mothers who brought their newborn children to the hospital to be vaccinated told me they were born in the camp and knew nothing about Somalia. They could only imagine how Somalia looked, from the stories they were told by their parents. Now, a second generation of children had been born in the camp. Most of them had parents who had left Somalia in the early 90s during the peak of the tensions. It was interesting and sad to hear that they had been born here. They all worried about the news of the closure of the camp. It was not the first time that the authorities had made this kind of announcement.

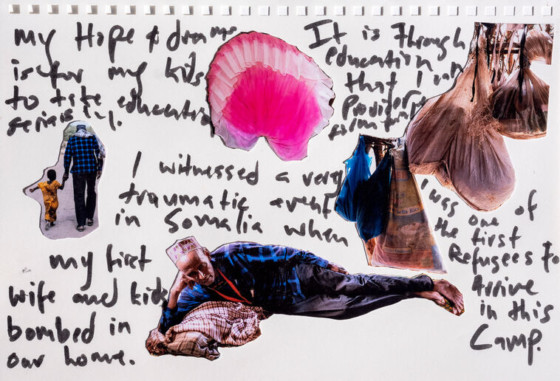

Through the conversations I had with the refugees about the camp, I had the idea of collage. Collaging all these experiences of individuals made sense for me. For example, I created a collage of a father lying on a blanket. Within the same image, there’s another image of him walking with his daughter, and with just a few of his clothes. His name is Khasim; he left Somalia in the 90s. He had experienced a traumatic event that still haunts him today. He witnessed his first wife and his children being bombed. I think he was coming home from work; he was about to enter their house. There was an explosion. So, all his family died like that. He came to Kenya on foot with his siblings. I think MSF was one of the organisations that came to help him. He was recruited by MSF, like some other refugees. He was one of the first people to work for MSF to run health promotion. He’s in his fifties now and one of his children is my age, currently studying medicine. His family was trying to find a way for him to continue his studies in Kenya or abroad. Education is the only hope for the Somali refugees in Kenya.

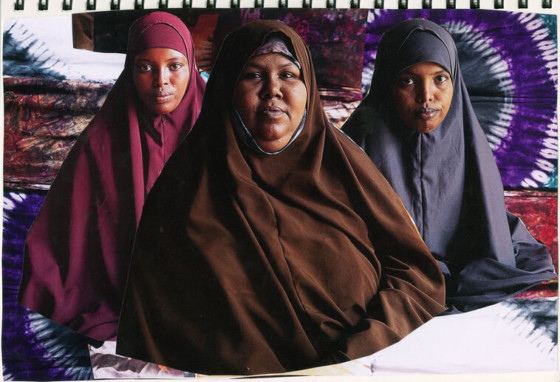

In another collage we see two girls, one in the front and one in the background. Their story is interesting. One of the two came to the camp in 2007. She belonged to a minority tribal group in Somalia, and her husband belonged to a majority clan. But because of the abuses she faced from her husband and his family, and for security reasons, she decided to escape Somalia. She arrived in Dadaab. I think at the time she was also having psychological trouble, so she joined one of the groups that works to empower women. These programmes helped her to develop skills and tools to overcome the difficulties. These groups help women to be independent and empowered, and she mentioned that some members of the community were against the idea of giving women a voice. As a result, she got shot, and no one knew who shot her: she showed me the bullet wound. But all these obstacles only encouraged her to keep on pushing and inventing. Now she’s an activist who is looking at the things that are against women, that are pressuring women, and she gives women the skills to face those difficulties. She also advocates for and promotes school attendance. I thought that was beautiful.

With the collages, I think I just wanted to bring those stories together. I was trying to give a collective experience of some sort, bringing all these different people together and putting them on the same page because the experience was interlinked in a way; because they left and because they are there. It brings together these unique, interconnected, collective experiences.

I did an interview with a lady who was born in the camp and I remember her saying that Somalia is not her home, it’s her mother’s home. She’s a refugee; she doesn’t have Kenyan nationality. Her dream is to have Kenyan nationality. Because that is what it means: belonging somewhere. It is also about normality. This refugee status is not right. It is not humane to have people living this kind of life, locked up. As a refugee, even if you are educated, you won’t have the same salary, and won’t get what a national educated person can get. The voices of the refugees are shattered, in a way. The Dadaab camp has existed for 30 years. It needs to be a community. It has its own market. It has most of the things that a community has. These are not camps of people living in plastic-sheeting houses; their houses have proper structures: walls and a roof. All they need is a helping hand, to find their strength and have hope. The people I met in Dadaab really inspired me to keep in mind: no matter what, just keep on pushing and one day something will come.

I think this experience made me realize how lucky I am to be living where I live. I’m privileged to be able to have a passport to say I exist, I have a home. What about the people who are in the camp? They don’t have that. I know that there is someone in Dadaab right now who would wish to have the life that I live. I’m also privileged to be a photographer, to be able to translate one person’s story for whoever will see the story. I’ve always seen my role as a photographer as that of a critical observer; to perhaps be a mediator, a kind of link between people. I have always wanted my images to change something, even if it’s one’s perception about a place. I remember I met someone who once told me: whatever the situation is, keep looking to see beautiful human beings with good hearts.