Sorry For the War

Peter van Agtmael and Tanya Habjouqa discuss the photographer’s new book ‘Sorry for the War’, its immediate follow-up publication ‘2020’, and examine “violence at the heart of America”

Peter van Agtmael’s new book Sorry For the War and his smaller booklet 2020 explore the spiralling, occasionally surreal, often dire effects and complexities of present American reality. Like their predecessors Disco Night Sept. 11 and Buzzing at the Sill, these explorations are rooted in the country’s foreign and domestic policy doctrines of the post-9/11 era. In van Agtmael’s words, Sorry For the War “chronicles the disconnect between the United States at war and the wars as they really are.”

Here, van Agtmael discusses the new works with Jordanian-American writer and photographer Tanya Habjouqa, his fellow mentor in the Arab Documentary Photography Program. The pair discuss nationalism, identity, and the “violence at the heart of America”.

Both Sorry For the War and 2020 are now available to purchase here.

Tanya Habjouqa: You and I have evolved together in the process of mentoring in the Middle East and we both enjoy helping other people dig into their narratives. I think it’s opened up our minds. There’s been an evolution in our own work, but we’ve also influenced each other. You’ve been a great influence on how I think about photography.

Peter van Agtmael: I think you’re right. I mean, it’s no coincidence that I started Sorry for the War at the end of 2014, which is exactly when we started teaching the Arab Documentary Photography Program. So much of what I’ve learned about the Middle East, I’ve learned from being part of this program. I’ve probably learned more than I’ve taught.

Do Disco Night Sept. 11, Buzzing at the Sill, and Sorry for the War form a trilogy?

Not really a trilogy, because 2020 is part of it too, but these books do seem to be the end of a thread of thinking that’s lasted these past 15 years. The year 2020 was, to me, the culmination of recent American history. It embodied all the political forces that have been in motion for the last few decades, where nationalism and identity politics took the forefront again. I see September 11 as being a moment that provoked the resurgence of those phenomena in this country. Over recent years, we’ve had a president who created an atmosphere of deep fear by exploiting the idea of threats to this country, our freedom, our security. So, when I look at the presidency of Trump, I see the post-9/11 world written all over it. That attack gave us license to use our fears as an excuse for anything. I think you can look at recent history as a guide, but you also have to look at the totality of American history as a framework. Things don’t just happen because of one event, they happen as part of the continuum of history.

"When I look at the presidency of Trump, I see the post-9/11 world written all over it. That attack gave us license to use our fears as an excuse for anything. I think you can look at recent history as a guide, but you also have to look at the totality of American history as a framework"

- Peter van Agtmael

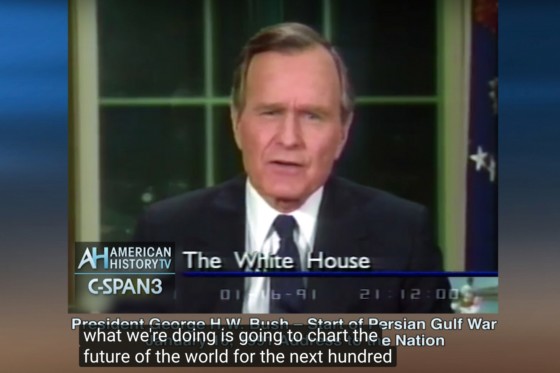

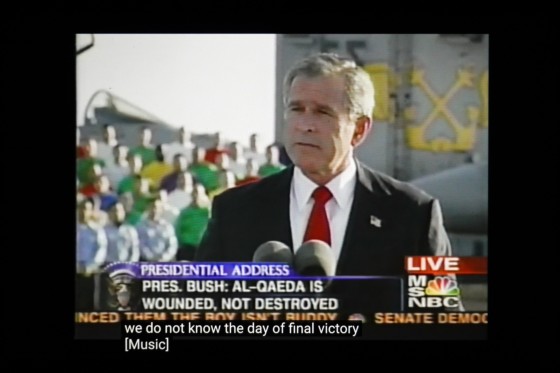

I’ve never been one for nationalism, let alone American nationalism. I’ve always been a bit cynical, but I think a lot of us got quite emotional during the [2021] inauguration when we really understood that the period you just described was over. The irony for me is that, sitting here today, looking through these books, I think we’ve been over-focused on the trauma of these last four years. In fact, this ugliness began long ago, and that’s one of the things I find quite interesting. I love how in Sorry for the War we step out from the photographs into the subtitled news screenshots about “ending the war”, from George Bush Sr., to Bush Jr., to Obama, then, of course, finally Trump. It’s sort of like a reminder. We’ve been so focused on these last four years as a festering scab, but the ugliness that you’ve been documenting began long ago.

Well, the ugliness began, in some ways, in 1492, right? I mean, the whole history of the country is based on conquest. This was a vast land, sparsely populated by Native American tribes. And it was seen as a place that was ripe for people to come and make a fortune, or flee from religious persecution in Europe. Of course, the tragic irony of persecution is that it’s often times the persecuted that then employ the same tactics when given the power and opportunity. Anyhow, the conquest slowly began, but accelerated as America became sovereign from the English, and America institutionalized expansion in the form of Manifest Destiny. In the process, through disease and through conflict, the native population was largely eradicated. So, the triumphant history of the country has always been based on the violence of conquest.

"2020 is a diary and a first draft of history, whereas Sorry for the War is a kind of nonlinear rendering of something that comes from within. In 2020, everything I did was reactive to the fluidity of events, and my pictures are a little weird and surreal."

- Peter van Agtmael

True. You mentioned that you see the book 2020 as a continuation, but there’s something so painful about it. You have moments of levity in it, in particular there’s the floating baby Trump balloon, then there’s that beautiful image I can’t get out of my head, of the black gentleman dancing beside the National Guard soldier, while in the background is this woman who’s suspected to be on opiates falling asleep... There’s levity, but there’s heartbreak. I think 2020 is just so loaded with the apex of shit of the last four years. It’s a manifestation of a new nadir of how ugly America could be. It’s painful [to look at].

Sorry for the War, on the other hand, is so incredibly smart and beautiful – it’s like a visual novel – and the brutality is there, but something about the way that it is thought out means that it just moves differently. I see 2020 as something else, it hurts me somehow more. There’s the… I’m gonna say the word that you mock me for saying… I’m gonna say ‘liminal’.

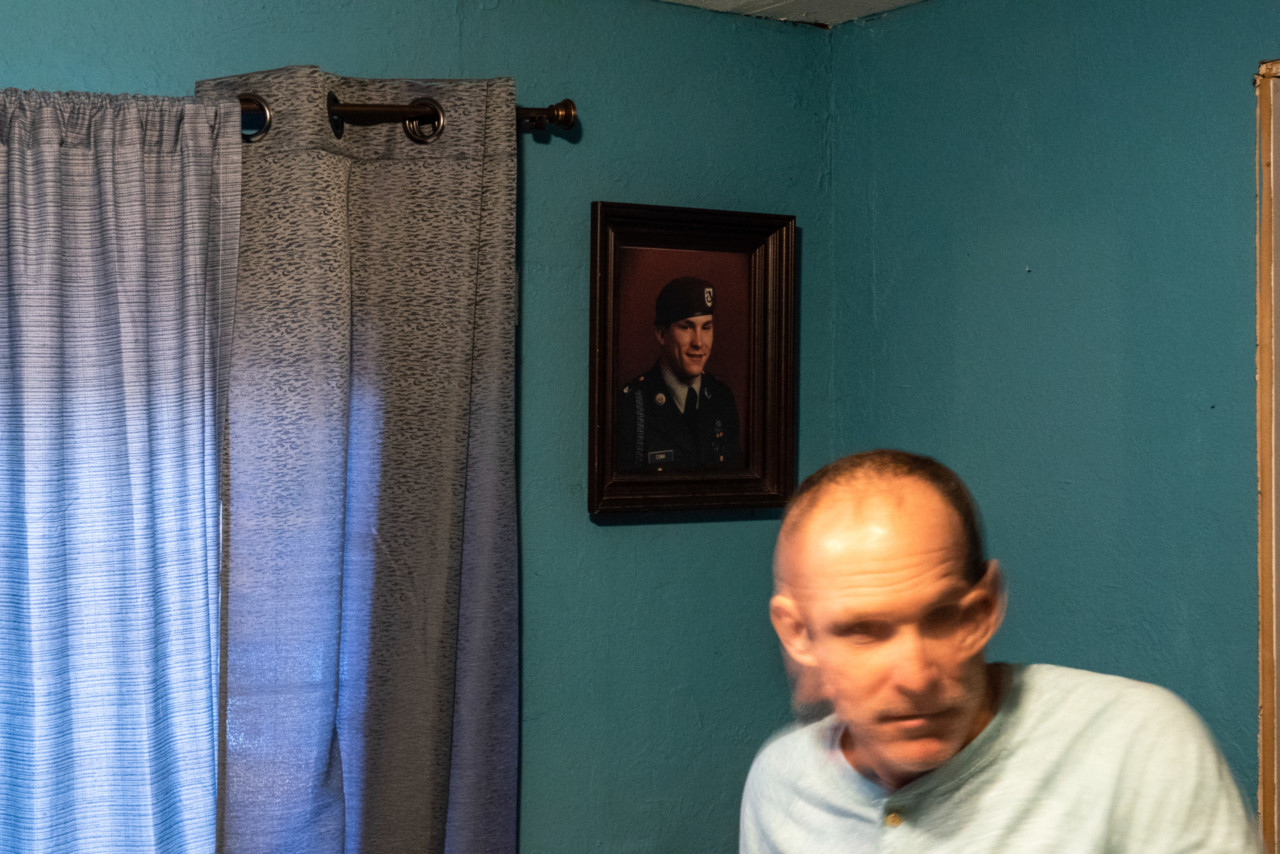

Your work is sublimely liminal: these awkward zombie–ike movements of people caught in between moments, and things covering peoples’ eyes, that speak to transitions. There’s the diary aspect to your projects: you always slipped in your best friend, you always slipped in your family. But you revealed a little bit more as it evolved with each work. And this new work is on another level. And I see the complexity in it and I see you.

Well 2020 is a diary and a first draft of history, whereas Sorry for the War is a kind of nonlinear rendering of something that comes from within. In 2020, everything I did was reactive to the fluidity of events, and my pictures are a little weird and surreal.

My thoughts about this country, and the consequences of its actions abroad have come in various stages. The first stage was very much an interest in the US military and what the US military was doing abroad, which in turn started a political reckoning of deep disgust at the nature of the American occupation. The pointlessness of it, the horror, and the violence, and all of it so invisible. And this feeling of impotence of having seen so much of it, yet having also seen only a tiny part of it. And the impotence of then trying to make a coherent work out of those experiences and get it out into the world, which could only still ever be a marginal act, because there is no clearly defined mass market for books like this, even if they relate to a subject of national importance.

Of course, all the books I’ve done are interrelated. They are about my interpretation of history from the framework of my identity as an American. And the United States is the farthest thing from a monolith. I try to make that positioning clear as well, I’m not an authoritative voice. I try and think deeply and clearly but at the end of the day my perspective is limited. When I went into this work at 24 years old, I was coming out of elitist institutions, and my vision and window on the world was a by-product of that upbringing. I knew liberal, white, prosperous suburbia. That’s it. And that’s a very small part of the country. It took spending a lot of time with the military, a cross section of class and race, in the exceptionally challenging atmosphere of war— through that, many questions were raised for me about this country, and about myself. The ever-present threat of death or bodily harm created a kind of clarity, while also heightening my confusion and uncertainty. Certainly, it was all very humbling. And yet, my success in navigating it also inflated my ego. So, a lot of contradictory forces were at work, which have taken a lot of time to sort out. Of course, they are far from resolved, and probably never will be. But it’s worth trying to reckon with the contradictions of being human, which is in part a reaction to the reductive reasoning that is so fashionable in society these days. The more complex things get, the more people want to pretend to be authoritative. I would find that narrow kind of thinking embarrassing, if it wasn’t so dangerous.

"I realized, especially as I became successful as a photographer and began getting big assignments to cover wars, that I had an enormous amount of power. My version of history was going to be given a lot of weight because it was validated by the structure of power"

- Peter van Agtmael

Do you feel like you wear a mask as a photographer: as a means of fitting in to what you’re photographing, a means of coping with it?

When I first became a photographer, I didn’t really know what it meant to be a photographer. It felt right, but it was also overwhelming. I was kind of myself, but I was mostly channelling my influences. I didn’t know how to slow down time, and everything was so new to me. In that first year in Iraq, I just had a fixed wide-angle lens on my camera. Most of the time I didn’t even raise the camera to my eye, I just got close to scenes and clicked the button. I was just feeling it and getting close to it and wasn’t thinking about the edges of a frame or layering or all the virtuosic things we think of as “good photography”, I was just in the moment. Now I am a bit more stepped away and calculated about my process, because my experience is colored by the knowledge I’ve gained in the years that have followed. And perhaps that makes the work a bit more detached. I think surrealism is the way I cope with 15 years of witnessing a lot of extremely painful and traumatic things. Creating a dystopian fairy tale universe of the world as this sort of strange and baffling and mysterious and tragic place, which holds moments of transcendent beauty. So yeah, that’s a mask of sorts.

"This book is my apology, and a statement of helplessness, about what has happened these past two decades. I can’t change any outcome, but I can certainly create a rigorous document interpreting what's come to pass..."

- Peter van Agtmael

Do you question now if you’re the best person to tell the story? Because I actually think the Arab Documentary Photography Program has affected you. I think that you have supported initiatives that gave other people a platform, and you really fostered opportunities for other people. And I wonder if that was also part of the realization and questioning of your role? I feel like you actually went into a more complex stance of enabling others.

Early on in photography, I wasn’t thinking about questions of identity politics, or where I come from, and what that might mean about the kind of pictures I was taking. But over time, the more experience you have in the world, the more people you meet, you can’t escape those questions really. And so, they have become critical to my thought process. The way photography has been used as a tool of power and a tool of manipulation and how photography itself relates to the dehumanization of whole aspects of society, both domestically and abroad. I realized, especially as I became successful as a photographer and began getting big assignments to cover wars, that I had an enormous amount of power. My version of history was going to be given a lot of weight because it was validated by the structure of power. And that gave me a certain amount of pride, but it also scared me. Simultaneously, I was being humbled by my lack of knowledge and understanding, and the limits of my perspective, and the fact that photography is a continuum of many kinds of voices and many kinds of visions. If I wanted to do right by my growing belief system, I needed to find a way of integrating all those things together to help push forward the kind of voices that I thought could tell a different kind of story. All towards the goal of a more honest, complex, thoughtful rendering of reality. Which is where the work we’ve done in the Arab Documentary Photography Program together with Randa Shaath, Eric Gottesman, Jessica Murray, Bertan Selim and the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, the Magnum Foundation and the Prince Claus Fund comes in, along with other initiatives.

"I’ve come to know the violence at the heart of America very well. The generosity and grace as well, but just this unremitting violence. When my eye is directed towards the Iraqis, Afghans, and Syrians caught in the middle of this mess, it's a lot more gentle"

- Peter van Agtmael

I think what I appreciate about this work is your gaze and that you spent a lot of intense time with the individuals whom American politics were affecting. I’d love to dig into some of the work in Sorry for the War. What’s the meaning of the title?

The title comes from a photograph I took of a handwritten note I saw at this weird pop-up thing at an art gallery in New York, called “Balloons for Kabul”. New Yorkers wrote notes to the people of Kabul that would be handed out to them with pink balloons during their morning commute. It was a well-intended but totally out of touch response to a then already decade-long conflict. Much of the work that I do is about the disconnect between the US and the consequences of its — or of our — imperial actions abroad. That note, and that event, seemed to symbolize a lot of my mistrust and cynicism I had for our distorted idea of collective empathy.

And that note seemed appropriate because this book is my apology, and a statement of helplessness, about what has happened these past two decades. I can’t change any outcome, but I can certainly create a rigorous document interpreting what’s come to pass. And I think that’s partly why the gaze on the Americans in this book is kind of brutal, and mocking, and sardonic. I’ve come to know the violence at the heart of America very well. The generosity and grace as well, but just this unremitting violence. When my eye is directed towards the Iraqis, Afghans, and Syrians caught in the middle of this mess, it’s a lot more gentle. And that’s partly because I have a greater degree of sympathy for the true victims of this conflict. And partly it’s a reaction to the fact that these groups have generally been visually marginalized and only seen in moments of extreme violence and grief over the history of photography. I want to push back against those forces.

"I think it's important because we tend to see things in black and white. We sentimentalize those who we perceive to be our heroes. But if you look at the history of American power, violence, and empire, it’s a bipartisan issue. I don’t want to shy away from that."

- Peter van Agtmael

I think your use of flash is a strength in how you present these surreal scenes. Do you intentionally use it to play up that surreal feeling?

Oh, it’s very intentional. Unlike a lot of photographers who chase light, or composition, I’m chasing content. So I end up in a lot of scenes where the lighting is terrible, like a hotel conference room. Flash is partly a way of compensating for bad light. But because it flattens everything out and fills in every crack and crevice and shadow it also creates this sort of plasticky two-dimensional feel that is exacerbated by the qualities of the digital file. In this way reality becomes simultaneously more abstract, and more clarified. I take the craft very seriously, though I try not to be too obvious about it, or too manneristic. Style can be a crutch.

There’s a particular sequence of images in the book which come after the screenshot of Obama. I found them incredibly troubling because I think by comparison with what followed in Trump, Obama came to be seen as some sort of ideal. But Obama really was disappointing in a lot of ways. I mean, being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize upon [being elected], without having even shown what his intention or what his policies would be.

Well, Obama was given the Nobel for the symbolic power of his election, not his actual policies. Anyhow, I think it’s important because we tend to see things in black and white. We sentimentalize those who we perceive to be our heroes. But if you look at the history of American power, violence, and empire, it’s a bipartisan issue. I don’t want to shy away from that. A lot of violence happened during Obama’s presidency, and history will probably show that some of his actions, for example the surge in Afghanistan, were as much cynical political moves as they were things that would have a pragmatic effect on the outcome of the war. And at what cost? Don’t get me wrong, George W. Bush is a war criminal, but the burden of responsibility goes deep.

Still, no matter which way you slice it, the decision to become president of this country will taint you with violence and moral ambiguity. It’s very surreal to imagine that kind of power, that one person holds the fate of history in the decisions they make. But I also shy away from two-dimensional renderings of the significance of these figures. Polemics are generally cheap and thoughtless: easy answers to complex realities.

"No matter which way you slice it, the decision to become president of this country will taint you with violence and moral ambiguity"

- Peter van Agtmael

I see you as a visual writer. You are adept at putting that feeling into a picture: like a feeling one finds in a favorite passage of a novel that breaks your heart. I love this work. And I hope, I wonder, is there a feeling of release now? Or is there heartbreak? Because the work that follows this in 2020 has – as we discussed – levity, but also lot of heartbreak. I mean, where are you now? Where’s the little boy who was obsessed with Life magazine imagery and ended up at war?

There’s a lot of release and relief because after 2020 I feel like this vague shadow of an idea I started off with 15 years ago is getting close to ending. I came in with a lot of naïveté and insecurity and egocentrism and the desire to prove myself, which mixed awkwardly with political belief and idealism. But over time, it kind of crystallized into a mission. I hope this work is a testimony for the present, but also something that will linger for history as well. With the completion of these four books, I sort of feel like I’ve achieved that abstract notion of what I set out to do. But the work has also opened up so many other doors to aspects of the United States to look at, to scrutinize, and to dissect. It’s given me this kind of clarity about where I want to go next with this work. So, there’s this feeling of great satisfaction and relief, and also heartbreak and pain and uncertainty. Mixed with resolve towards what’s next and what I’m here to do on this planet in my short little time I have to live on it. There’s a certain security and comfort in that realization. Of course, within that clarity is the knowledge that all these choices have a cost.