The Pleasures and Denials of Window-shopping

Magnum’s photographs have documented the relationship between our consumerist urges and the act of looking

Virginia Woolf knew a thing or two about looking in shop windows. In her novels it’s an activity her characters engage in frequently, observing “shopkeepers… fidgeting in their windows with their paste and diamonds” (Mrs Dalloway) and displays “full of sparkling chains and highly polished leather cases” (Night and Day). Sometimes they find what they see discomfiting. In The Waves these gleaming temples of consumerism overwhelm Bernard, who begins to list his own “sensations, spontaneous and irrelevant, of curiosity, greed, desire, irresponsible as sleep. (I covet that bag – etc)” while he walks. Finding himself “unmoored” in a crowd, he comes to question what his place is among “these errand-boys and furtive and fugitive girls who, ignoring their doom, look in at shop-windows?”

Glimpses through glass also turn up frequently in the author’s essays, whether in the form of objects and goods speculated about during long walks through London, or the sensory overload of the “perpetual ribbon of changing sights, sounds, and movement” experienced as the writer traverses Oxford Street. In her brief piece penned for Women’s Leader in 1920 titled ‘The Plumage Bill,’ the neighbouring Regent Street is described in equally vivid terms: “One might string substantives and adjectives together for an hour without naming a tenth part of the dressing bags, silver baskets, boots, guns, flowers, dresses, bracelets and fur coats arrayed behind the glass.”

The essay itself is broadly focused on a failed parliamentary attempt to restrict imports of feathers for hats, and specifically concerned with journalist H.W. Massingham’s criticism of women’s love of fashionable plumage. In its response, however, it also provides a perceptive portrait of the pleasures and denials of window shopping. “Men and women pass incessantly this way and that. Many loiter and perhaps desire, but few are in the position to enter the doors. Most of them merely steal a look and hurry on.” Only the fashionable Lady-So-and-So – an invented figure of “a different class altogether” with white gloves and “lustrous” shoes – has the ability to step inside and purchase what she sees. “The look she sweeps over the shop windows has something of the greedy petulance of a pug-dog’s face at teatime,” Woolf writes dryly.

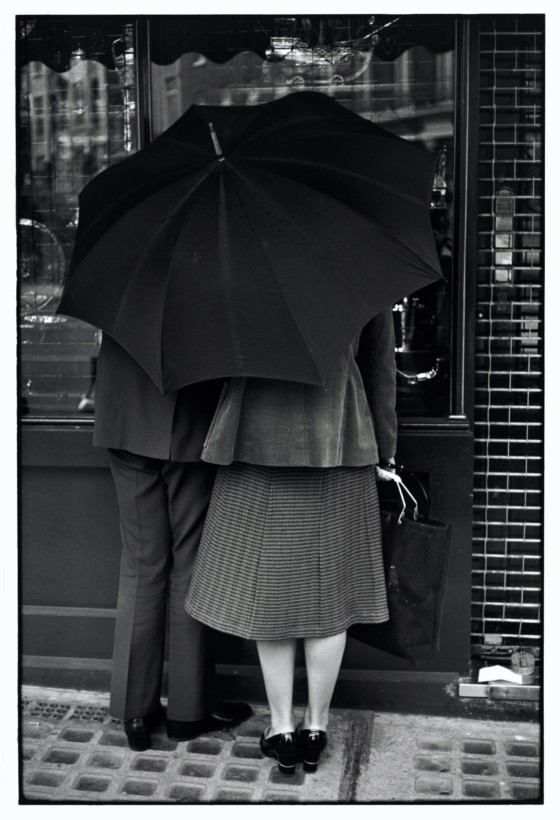

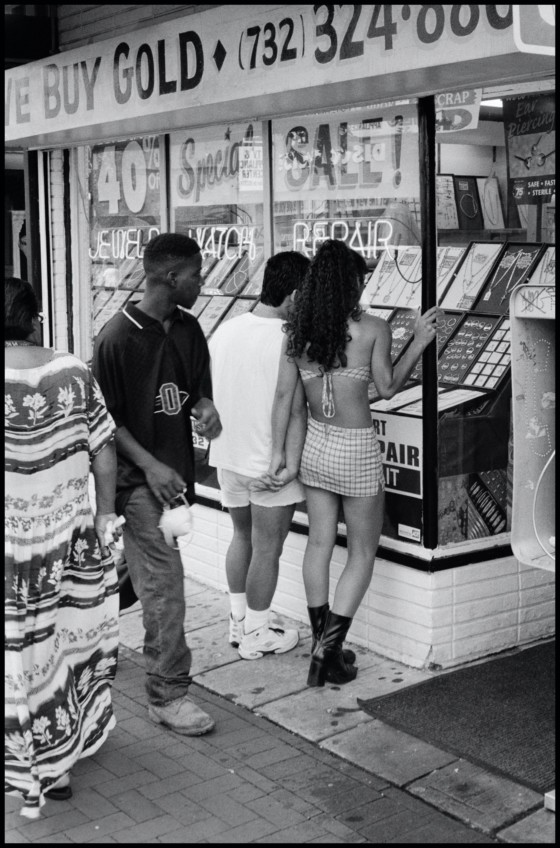

This funny little essay with its mention of stolen looks and the difference between desire and purchase is a useful one to keep in mind while exploring Magnum’s wealth of shop window pictures. Here we enter the realm of sidelong glances, longing stares and small noses pressed against glass; offered intimate glimpses into the lives of avid shoppers and casual passersby. These images serve as illustrations of the idle pleasures of browsing, as well as reminders of distance: each window becoming a portal into a world exhibited behind glass, figuring, as Rachel Bowlby writes in Just Looking: Consumer Culture in Dreiser, Gissing and Zola, as “both barrier and transparent substance, representing freedom of view joined to suspension of access.”

In the images caught by Magnum’s photographers, those tempting views are many and varied. To repurpose Woolf, one could string together substantives and adjectives for an hour without naming a tenth part of the watches, wigs, jewels, cocktail dresses, veils, suspender belts, orthopedic legs, pineapples, scent bottles, wedding cakes, paper flowers, radios and t-shirts reading “show me your tits bitch!” arrayed behind glass in these photos. The same goes, too, for all the different categories of observer caught lingering over these displays, whether old men with hands clasped behind backs, well-dressed women walking equally coiffed dogs, restless crowds waiting for shop doors to open, or excitable children daydreaming about things they cannot have.

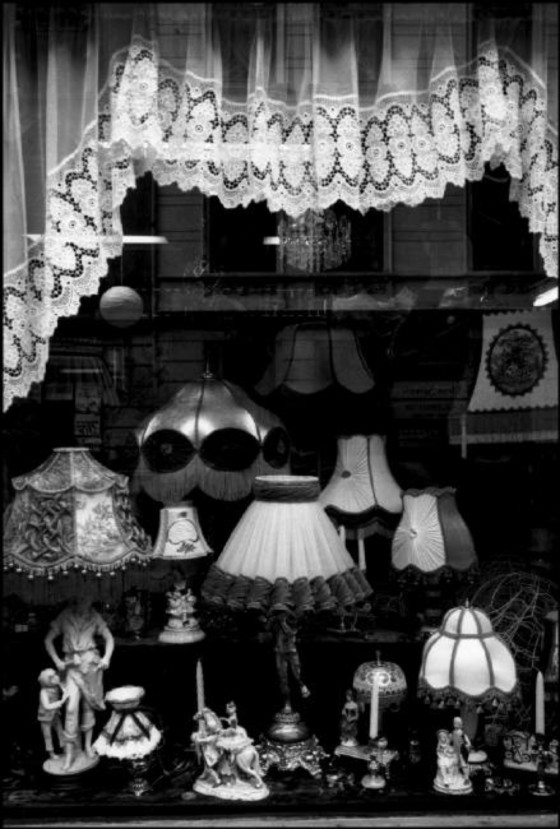

In some of the photos there are no observers at all: only static mannequins, or arrangements of paintings or lamps. The mannequins make for eerie viewing. In Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photo taken in Manhattan in 1946, a static bride surveys the street through unblinking eyes. In another taken in Germany in 1931, a lingerie-clad figure is glimpsed through a high window, the arrangement reminiscent of a shadowy Hitchcock heroine. In other photos mannequin and human face off. Elliot Erwitt’s portrait taken in Wilmington in 1950 is a particularly brilliant example. The mannequin is bald, armless, and naked but for what looks like a waist waspie. It leans forward in the foreground, its pose somewhere between curious and suggestive, smooth face tilted towards the woman on the street outside glancing back in what looks like surprise.

The poet Mina Loy, who was born the same year as Virginia Woolf, also wrote frequently about shop windows. In her 1915 poem ‘Magasins du Louvre’ she turns her focus towards the uncanniness of mannequins: “They alone have the effrontery to/ Stare through the human soul/ seeing nothing/ Between parted fringes.” In many of these photos that same sense of absence is conjured, a juxtaposition set up between the active observation of the people looking in and the glassy stare of the simulacra who stare out. The latter’s gaze is disconcerting not just because it is inanimate, but because it is vaguely inviting. In their human likeness these figures encourage identification: asking would-be shoppers to imagine themselves too in a liquid gold gown, or a straw sunhat, or a lustrous shoe, suddenly picturing a new self that could be brought – or rather bought – into being.

"In many of these photos that same sense of absence is conjured, a juxtaposition set up between the active observation of the people looking in and the glassy stare of the simulacra who stare out."

-

Images of shop windows always have something to say about watching, and its relationship with the ever-roving, ever-wanting imagination. Woolf and Loy both also wrote about the eye in motion, the former describing it as “a central oyster of perceptiveness” while the latter called it “a commodious bee” gathering “infinite facets.” The great pleasure (as well as potential furtiveness) of window shopping is found in the act of looking without necessarily buying, the eye darting and dashing where it pleases, alighting on surfaces and absorbing whatever it happens to find there. Perhaps this activity precedes purchase, the window becoming a site of careful selection and spontaneous decision. Perhaps it is a source of frustration, simultaneously tantalizing and alienating those who cannot afford what they see.

No wonder then that so many of these photos alight on the backs and sides of people’s heads, capturing fleeting moments of window-side dawdling. In Thomas Hoepker’s 1975 photo in East Germany, a colourful crowd clusters around a small shoe display. In Rene Burri’s 1979 photo in New York, we experience both the bustle of a city – a man passing by in the foreground, slightly blurred – and the crisp stillness of two white-haired women paused outside Elizabeth Arden. In Erich Hartmann’s 1965 portrait of a man standing in front of a gift shop window, there is a sense of all-encompassing anonymity: any of us, after all, could be an unknown figure clad in black, head bent towards glass to examine things that sparkle and catch the eye, experiencing that complicated mix of curiosity and covetousness described so precisely by Bernard in The Waves.

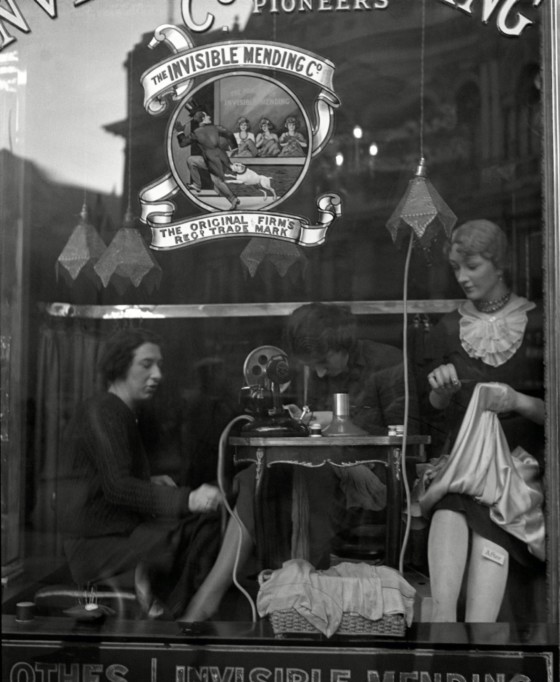

We have an advantage though. Unlike the casual window shopper, as viewers we are not relegated to being stuck on the outside looking in. The photographer’s eye darts and dashes too: zeroing in on the texture of lace; observing shop assistants changing displays; catching all manner of reflections as transparent glass briefly becomes a mirror. As it moves, the camera brings us with it. We watch the watchers, and browse the goods for ourselves. Sometimes we end up on the other side of the glass, staring out through net curtains at a busy thoroughfare, or nestled down among the displays, our eye-line suddenly the same as those unseeing mannequins. We are placed in the position of observed spectacle, free to scrutinize the emotions of those who pause and stare at what’s for sale: the nosiness and boredom; the flashes of longing and wonder; the moments of unbridled greed; the faces deep in concentration deciding what they like, or hate, or wish for, or plan to pluck from the window and take home. For us, time briefly slows – our view reduced to a series of still objects, and the odd stolen look before the world hurries on.