Inside Madame Helena Rubinstein’s Beauty School

The story of émigré entrepreneurship and all-American commerce behind Inge Morath's photographs of groundbreaking beauty businesswoman Helena Rubinstein's New York studio

Madame Helena Rubinstein never minced her words. “All the American women had purple noses and grey lips and their faces were chalk white from terrible powder,” she once said, of the demographic who would become her most doting clientele. “I recognized that the United States could be my life’s work.” And indeed, the 4ft1 acerbic cosmetics mogul – a predecessor to the likes of Estee Lauder, Bobbi Brown, Kevyn Aucoin and Francois Nars – laid the foundations of a beauty industry worth $445 billion (sales) according to Forbes, today. By the mid-1920s, the business bearing her name was worth $7.5 million, rendering Rubinstein one of the first self-made women to amass a six-figure fortune.

The story of how she came to claim such a title bears the hallmarks of entrepreneurial tenacity, alongside an eccentricity befitting of the early-20th century’s penchant for hedonistic glamour. Born in a Polish shtetl in 1870, Rubinstein emigrated to Australia at the age of 24. Almost penniless and speaking broken English, she was sent to work with her uncle in Melbourne as ‘punishment’ for refusing to marry a suitor she found to be less than fit for her discerning standards.

In her suitcases, she carried pots of her mother’s secret “Krakow moisturizing cream”, the product with which she launched her empire. Named Valaze, it was marketed as “a gift from heaven” for clients whose skin had wizened from repeated exposure to the blazing sun, “compounded from rare herbs which only grow in the Carpathian mountains”. With such rhetoric, the cream’s popularity grew, and so did its profits, eventually allowing her to lease her first salon in Melbourne in 1902 – The Valaze House of Beauty.

"I recognized that the United States could be my life's work

"

- Helena Rubinstein

Staying faithful to her promise to eradicate the blotchy pallor of the United States’ female population, Rubinstein set her sights on New York, emigrating and founding a second salon there in 1915. Despite the imminent Great Depression and the World War that followed, she would go on to open several other chains in the city, and never suffered a significant financial downturn.

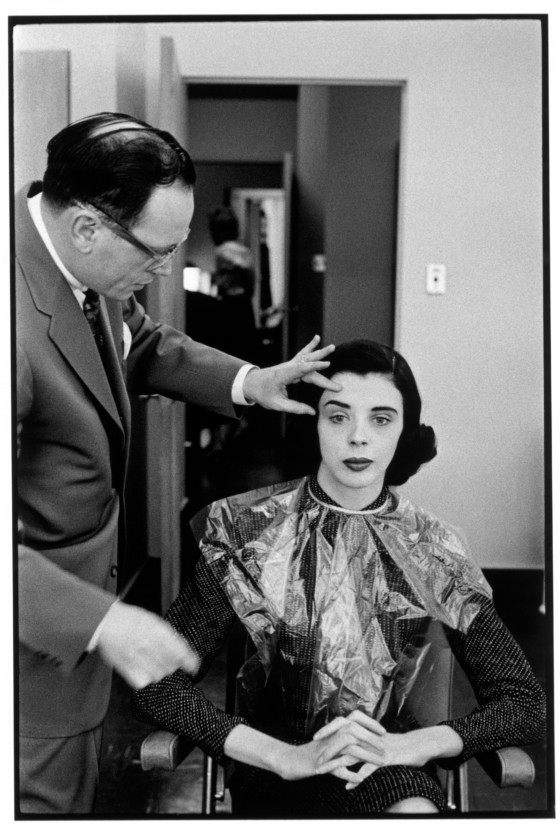

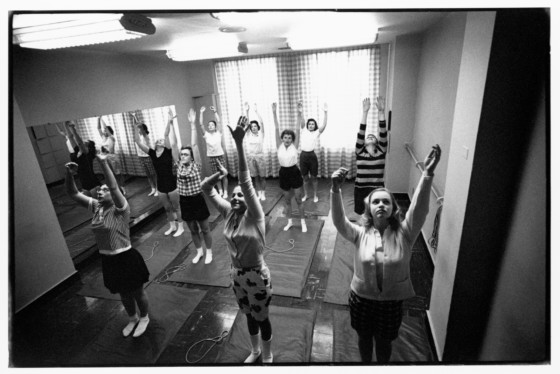

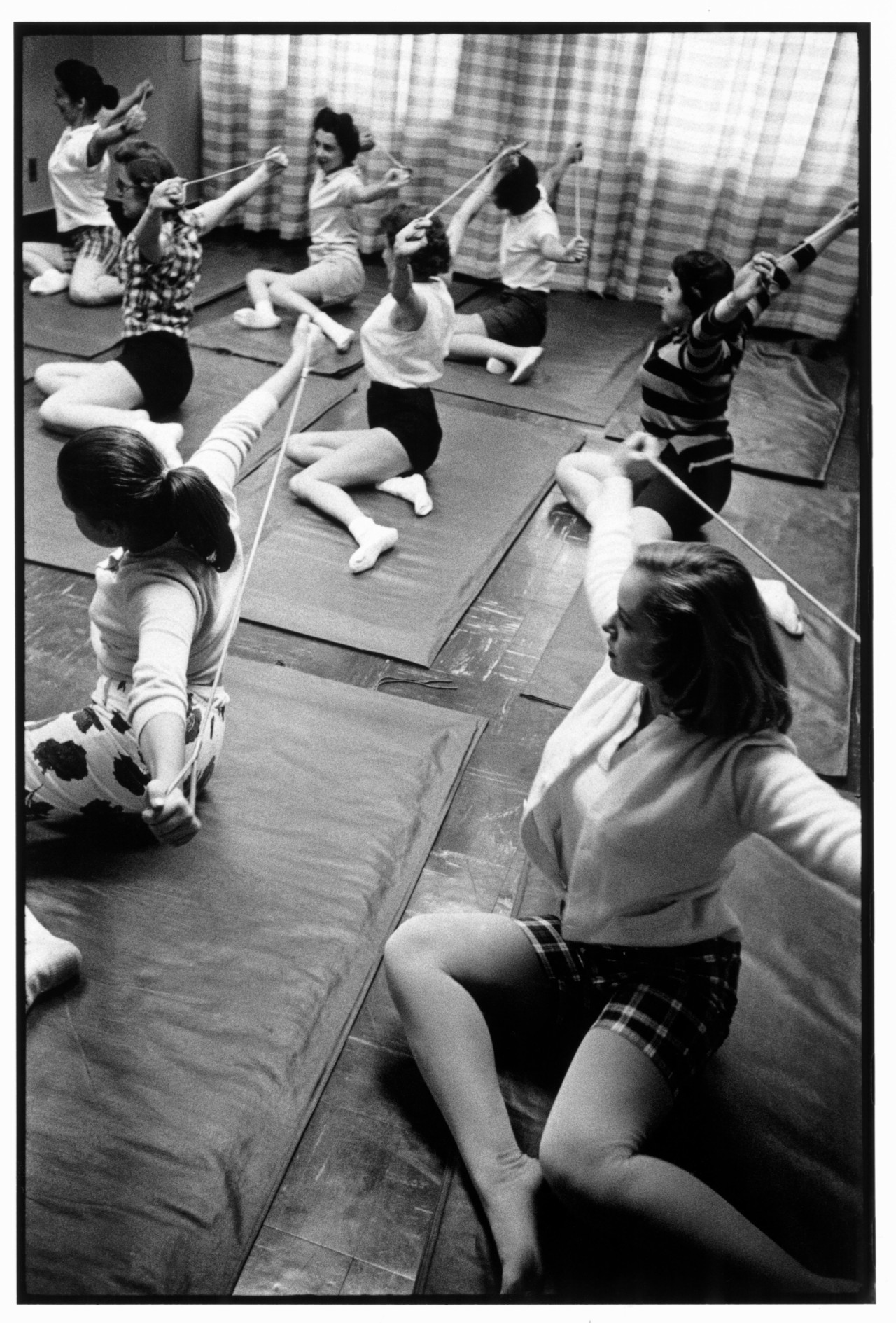

It was the exclusive nature of a Helena Rubinstein Salon that kept the business afloat, with each branch offering the most innovative services possible to the eager middle classes: from microscopic skin analysis, entire body ‘re-sculpting’ and balsam oil head steaming to soften parched hair set in the ubiquitous, chemical-laden permanent wave. Personalized diet and exercise regimes and training courses were also readily promoted, providing a 360-degree experience for the modern woman who no longer viewed health and beauty as a mere luxury, but a necessity.

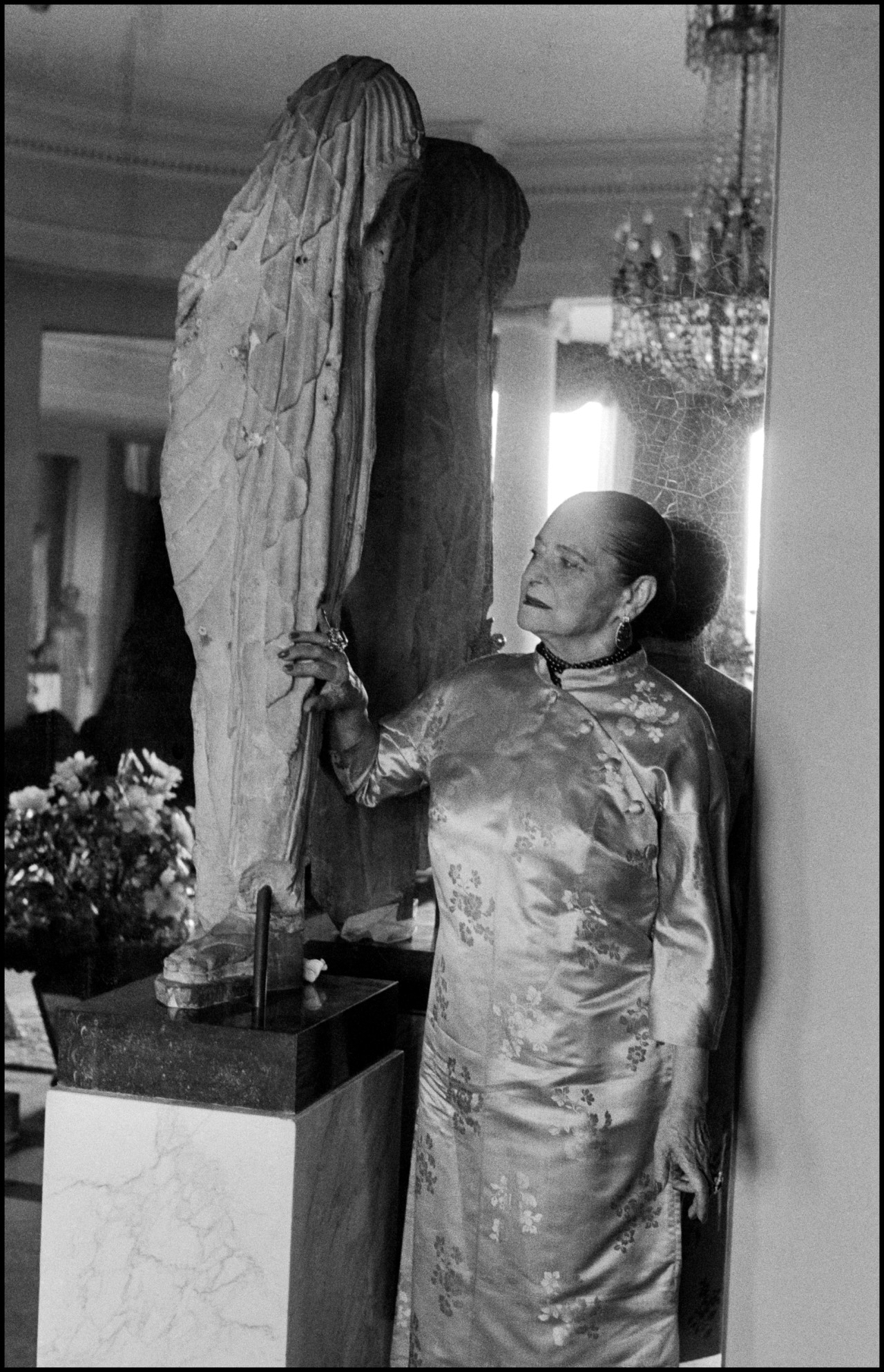

All of this was set against the backdrop of lavish interiors that were inspired by the literary salons of Europe. Rubinstein was an avid collector and patron of the arts, and as such, she frequently mixed with the likes of Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Man Ray, who went on to immortalize her in their respective mediums. Later in life, she would meet Andy Warhol, who captured her likeness in a line drawing, her signature slicked-back chignon and teardrop earrings remaining prevalent in the ink.

Rubinstein’s passion for the arts was reflected in the decor of her salons, and she commissioned works from Salvador Dali and Joan Miro to be hung on the walls. These were some of the inaugural spaces of the 1900s that blurred the boundaries between the art gallery, fashion store and spa; places that allowed women to be preened and pampered, whilst simultaneously feeling cultured by taking in their immediate surroundings.

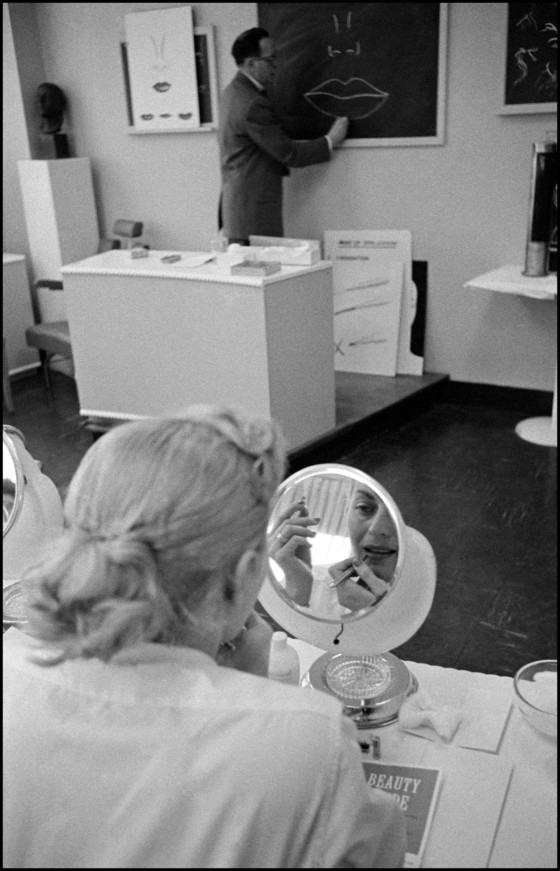

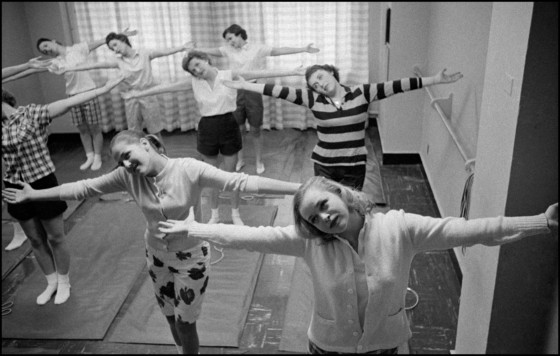

Helena Rubinstein did not go unnoticed by the lens of Magnum photographer Inge Morath, whose documentary work is renowned for depicting cultural figureheads in their most candid moments; including her famous portraits of Yves Saint Laurent and Cristobal Balenciaga, a designer whose sculptural clothes she deeply appreciated and frequently wore. Evidently, Morath and Rubinstein had a shared eye for the joy that can be garnered from looking at beautiful things, with Morath photographing the businesswoman at home, gazing lovingly at a piece from her art collection in 1957. The following year she visited one of Rubinstein’s salons to document its daily happenings, rendering lessons in how to achieve “the perfect brow” and aerobic classes from Helena Rubinstein’s “Five Day Wonder School” in her signature style.

"An army of women undergoing the painstaking ritual of a facial care at Helena Rubinstein, the procedure accompanied by quasi-scientific drawings on the board, in the end, the final result successfully demonstrated by the maestro on the ‘experimental object’ "

- Arthur Miller

“Women getting out of cars with lapdogs – the door opened by the commissionaire at Saks or Bergdorf Goodman and being shown the latest jewelry, the latest dresses, the latest porcelain for the next distinguished dinner party,” wrote playwright Arthur Miller, Morath’s husband, of the interest his wife in took in the slice of American society that Rubinstein embodied.

“An army of women undergoing the painstaking ritual of a facial care at Helena Rubinstein, the procedure accompanied by quasi-scientific drawings on the board, in the end, the final result successfully demonstrated by the maestro on the ‘experimental object:’ yes we’ve done it again.”

Certainly, through her images, Morath captured the essence of Helena Rubinstein’s manifesto, one that packaged and sold a dream: “For me, it is just as important to help a human being become beautiful as it is to sculpt a great statue or paint a fine portrait,” said ‘Madame’. “Works of art do not cross paths in the street every day, they don’t sit at the table opposite you.” But, in utilizing the subtle visual language in which she was fluent, Inge Morath also showed a ‘behind the scenes’ glimpse into reality: that maintaining such high standards of beauty can be extremely hard work.